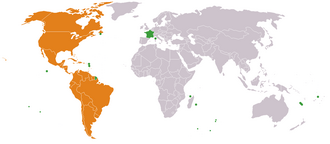

France–Americas relations started in the 16th century, soon after the discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus, and have developed over a period of several centuries.

Early encounters (16th century)

Expeditions under Francis I

In order to counterbalance the power of the Habsburg Empire under Charles V, and especially its control of large parts of the New World through the Crown of Spain, Francis I endeavoured to develop contacts with the New World and Asia.

In 1524, Francis I assisted the citizens of Lyon in financing the expedition of Giovanni da Verrazzano to North America. Verrazzano was an Italian in the service of the French crown. The objective was to explore the lands north of Florida and find a passage to Cathay.[1] Verrazzano was the first European since the Norse colonization of the Americas around AD 1000 to explore the Atlantic coast of North America between South and North Carolina and Newfoundland, including New York Harbor and Narragansett Bay in 1524: in between, John Cabot had already explored Labrador to the North, and the Spanish had already settled parts of Florida. On this expedition, Verrazzano claimed Newfoundland for the French crown.

In 1531, Bertrand d'Ornesan, Baron de Saint-Blancard tried to establish a French trading post at Pernambuco, Brazil.[2]

In 1534, Francis sent Jacques Cartier to explore the St. Lawrence River in Quebec to find "certain islands and lands where it is said he should find great quantities of gold and other rich things".[1] In 1541, Francis sent Jean-François de la Roque de Roberval to settle Canada and to provide for the spread of "the Holy Catholic faith."

Early Huguenot colonists

Soon, the Huguenots, whose Reformist religions was in conflict with the French crown, attempted to colonize the New World to find a new ground for their religion and to contest the Catholic presence there.

Huguenot pirates such as François le Clerc attacked Catholic shipping repeatedly, raiding New World harbours. The Huguenots raided Hispaniola in 1553, fighting against the Spanish Catholic presence there, followed by raid on Cuba.[3] La Havana was seized by Jacques de Sores in 1555.[3]

The first attempts at colonization were made under vice-admiral Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon, who was joined later by Huguenots Pierre Richier and Jean de Léry. After the short-lived establishment of France Antarctique in Brazil from 1555 to 1567, they had to abandon, and finally resolved to make a stand back in France, centering on the city of La Rochelle for the organization of resistance.[4]

The first French expedition to Florida occurred in 1562, composed of Protestants, and was led by Jean Ribault and permitted the short-lived establishment of Fort Caroline, named after the French king Charles IX.[5]

These first attempts at Huguenot colonization would be taken over by Catholics, following the Huguenot repression in the French wars of religion.

Expansion (17th century)

North America

Towards the end of his reign Henry IV of France started to look at the possibility of ventures abroad, with both America and the Levant being among the possibilities. In 1604, the French explorer Samuel Champlain initiated the first important French involvement in Northern America, founding Port Royal as the first permanent European settlement in North America north of Florida in 1605, and founding the first permanent French establishment at Quebec in 1608.

In 1632, Isaac de Razilly became involved, at the request of Cardinal Richelieu, in the colonization of Acadia, by taking possession of Port-Royal (now Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia) and developing it into a French colony. The King gave Razilly the official title of lieutenant-general for New France. He took on military tasks such as ordering the taking of control of Fort Pentagouet at Majabigwaduce on the Penobscot Bay, which had been given to France in an earlier Treaty, and to inform the English they were to vacate all lands North of Pemaquid. This resulted in all the French interests in Acadia being restored.

Robert de La Salle departed from La Rochelle, France, on July 24, 1684, with the objective of setting up a colony at the mouth of the Mississippi, eventually establishing Fort Saint Louis in Texas.[6]

The French colonial drive increased in the 17th century, the "conquest of the souls" being an integral part of the constitution of Nouvelle-France, leading to the development of the Jesuit missions in North America. The efforts of the Jesuits in North America were paralleled by the Jesuit China missions on the other side of the world.

In France, the Huguenots were finally defeated by Royal forces in the Siege of La Rochelle (1627–1628): Cardinal Richelieu blockaded the city for 14 months, until the city surrendered and lost its mayor and its privileges. The growing persecution of the Huguenots culminated with the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV in 1685. Many Huguenots emigrated, founding such cities as New Rochelle in the vicinity of today's New York in 1689.

South America

A colonizing party of 500 and a mission of four Franciscans were sent under a 1611 patent letter from the Regent Marie de Médicis.[7][8]

The colonial enterprise to found "France Équinoxiale" was led by Daniel de la Tousche, Sieur de la Ravardière, and François de Razilly.[8] The outpost would later become the city of São Luís do Maranhão.[8] The French arrived in the island in August 1612.[9] One of the objectives of the mission was to establish trade in brazilwood and tobacco.[9] When France and Spain (including Portugal in the Iberian Union) became allied through the marriage of Louis XIII with Anne of Austria in 1615, support for the colony was discontinued and the colonists abandoned.[9] The Portuguese soon managed to expel the French from the colony.[8]

In 1624, settlement along the South American coast in what is today French Guiana began.

West Indies

The French also started to establish smaller but more profitable colonies in the West Indies. A colony was founded on Saint Kitts in 1625, in sharing with the English until the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, when it was occupied in its entirety.

The Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique founded colonies in Guadeloupe and Martinique in 1635, and a colony was later founded on Saint Lucia by 1650. The food-producing plantations of these colonies were built and sustained through slavery, with the supply of slaves dependent on the African slave trade. Local resistance by the indigenous peoples resulted in the Carib Expulsion of 1660.

The most important Caribbean colonial possession did not come until 1664, when the colony of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti) was founded on the western half of the Spanish island of Hispaniola.

Consolidation and conflict (18th century)

Triangular trade

Triangular trade developed and became extremely prosperous one, marked by intense exchanges with the New World (Nouvelle France in Canada, and the Antilles). French cities of the Atlantic Coast, mainly Nantes, La Rochelle, Lorient and Bordeaux, became very active in triangular trade with the New World, dealing in the slave trade with Africa, sugar trade with plantations of the Antilles, and fur trade with Canada. This was a period of high artistic, cultural and architectural achievements for these cities. In the 18th century, Saint-Domingue grew to be the richest sugar colony in the Caribbean.

On 21 September 1711, in an 11-day battle, the Corsaire René Duguay-Trouin captured Rio de Janeiro in the Battle of Rio de Janeiro with twelve ships and 6 000 men, in spite of the defence consisting of seven ships of the line, five forts and 12 000 men; he held the governor for ransom.[10] Investors in this venture doubled their money, and Duguay-Trouin earned a promotion to Lieutenant général de la Marine.

Territorial conflicts in the North

Northern America became an important theater of the conflict between France and Great Britain in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), known as the French and Indian War. The royal French forces allied with the various Native American forces in a Franco-Indian alliance. The conflict, the fourth such colonial war between the nations of France and Great Britain, resulted in the British conquest of Canada. The outcome was one of the most significant developments in a century of Anglo-French conflict.

To compensate its ally, Spain, for its loss of Florida to the British, France ceded its control of French Louisiana west of the Mississippi. France's colonial presence north of the Caribbean was reduced to the tiny islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, confirming Britain's position as the dominant colonial power in North America.

The eastern half of Hispaniola (modern Dominican Republic) also came under French rule for a short period, after being given to France by Spain in 1795.

American war of independence

France soon became again involved in North America, this time by supporting the American revolutionary war of independence. A Franco-American alliance was formed in 1778 between Louis XVI's France and the United States, during the American Revolutionary War. France successfully contributed in expelling the British from the nascent United States. The Treaty of Paris was signed on 3 September 1783, recognizing American independence and the end of hostilities.

When the French Revolution led to war in 1793 between Britain (America's leading trading partner), and France (the old ally, with a treaty still in effect), Washington and his cabinet decided on a policy of neutrality. In 1795 Washington supported the Jay Treaty, designed by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton to avoid war with Britain and encourage commerce. The Jeffersonians vehemently opposed the treaty, but Washington's support proved decisive, and the U.S. and Britain were on friendly terms for a decade. However the foreign policy dispute polarized parties at home, leading to the First Party System.[11][12]

The Jay Treaty convinced Paris that the United States was no longer a friend. By 1797 the French were openly seizing American ships, leading to an undeclared war known as the Quasi-War of 1798–99. President John Adams tried diplomacy; it failed. In 1798, the French demanded American diplomats pay huge bribes in order to see the French Foreign Minister Talleyrand, which the Americans rejected. The Jeffersonian Republicans, suspicious of Adams, demanded the documentation, which Adams released using X, Y and Z as codes for the names of the French diplomats. The XYZ Affair ignited a wave of nationalist sentiment. Overwhelmed, the U.S. Congress approved Adams' plan to organize the navy. Adams reluctantly signed the Alien and Sedition Acts as a wartime measure. Adams broke with the Hamiltonian wing of his Federalist Party and made peace with France in 1800.[13]

19th century

Loss of Saint-Domingue

On August 22, 1791, a widespread slave rebellion began the Haitian Revolution, which culminated with the establishment of the independent Empire of Haiti in 1804.

Sales of Louisiana to the United States (1803)

Napoleon Bonaparte decided not to keep the immense territory of Louisiana that France still possessed. The army he sent to take possession of the colony was first required to put down a revolution in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti); its failure to do so, coupled with the rupture of the Treaty of Amiens with the United Kingdom, prompted him to decide to sell Louisiana to the young United States. This was done on April 30, 1803, for the sum of 80 million francs (15 million dollars). American sovereignty was established on December 20, 1803.

Mexico intervention

Under Napoleon III, the French led a major expedition to Mexico, in the French intervention in Mexico (January 1862 – March 1867). Napoleon, using as a pretext the Mexican Republic's refusal to pay its foreign debts, planned to establish a French sphere of influence in North America by creating a French-backed monarchy in Mexico, a project that was supported by Mexican conservatives who resented the Mexican Republic's laicism. But his imperial dreams in Mexico would end in failure. The United States was unable to prevent this contravention of the Monroe Doctrine because of the American Civil War; Napoleon hoped that the Confederates would be victorious in that conflict, believing they would accept the new regime in Mexico.

French role in the American Civil War

During the American Civil War, Napoleon III positioned France to lead the pro-Confederate European powers. For a time, Napoleon III inched steadily toward officially recognizing the Confederacy, especially after the crash of the cotton industry and his exercise in regime-changing in Mexico. Some historians have also suggested that he was driven by a desire to keep the American states divided. Through 1862, Napoleon III entertained Confederate diplomats, raising hopes that he would unilaterally recognize the Confederacy. The Emperor, however, could do little without the support of the United Kingdom, and never officially recognized the Confederacy.

During the tail end of the 19th century French foreign policy was focused on the Scramble for Africa, colonies in Asia, dealing with rising Germany in Europe. The Americas were not a priority concern.

20th century

French relations with the New World suddenly became of great importance, in the context of a wider search for new allies, once France was at war with Germany in 1914. Newfoundland, Canada, and the British West Indies were immediately at war as parts of the British Empire. The French Canadian population, however, was less than enthusiastic about the war, despite the appeals to defend the ancestral homeland. The eventual entry of the United States into the war was major boost to the Allies on the Western Front, including France, and it also paved the way for Latin American allies of the United States to declare war on the Central Powers (although they did not send troops to Europe) including Cuba, Panama, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Honduras, and Haiti. Brazil did send a naval contribution against German submarines.

Following the war, France was again occupied with European and colonial matters, and especially with the threat of German rearmament. Following the Fall of France in 1940, France was represented by two rival governments that attempted to gain international recognition, and maintain relations with the New World. The conflict between the Free French movement and the Vichy regime came to the Americas with the 1941 capture of the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon by the Free French. As in the last world war, the eventual entry of the United States into the conflict signaled the approach of the majority of Latin American states. On 21 July 1940 the Pan American Union created a regional defence pact in the Americas to keep out Axis forces, but few Latin American nations sent troops to Europe. The greatest impact of France's ties to the New World during the war, and perhaps in all of French history, were the contributions of the American and Canadian forces that landed in Normandy during D-Day, and participated in the subsequent Liberation of France. In fact, General de Gaulle landed at Juno Beach, where the Canadians had first come ashore.

Following the war, France entered into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization with Canada and the United States to deter a repeat of France's occupation by an invading power, this time the Soviet Union. France relations with (at least this part of) the New World were now much closer than for a century, but strains were now far in coming. Both Canada and the US refused to back France's action during the Suez Crisis in 1957, and encouraged quick French decolonization in Africa. Tensions with the English-speaking countries of North America became especially tense once Charles de Gaulle became president in 1958. He upset the United States by withdrawing French forces from NATO's command structure in 1959. And he angered Canada by seeming to support Quebec's secession in his 1967 Vive le Québec libre speech in Montreal.

Since the 1950s, France has also been involved in building the European Economic Community (now the European Union) into a major world trade bloc, which has often led to trade disputes with the New World countries, especially over the issue of agricultural subsidies and tariffs.

See also

- France–Africa relations

- France–Asia relations

- French colonial empire

- French colonization of the Americas

- Overseas France

- CARIFORUM, as part of EU-African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States

- EU-ACP Economic Partnership Agreements)

- ACP-EU Development Cooperation

- Association of Caribbean States (ACS)

- Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

Notes

- ^ a b North America: the historical geography of a changing continent Thomas F. McIlwraith, Edward K. Muller p.39ff [1]

- ^ Renaissance Warrior and Patron: The Reign of Francis I by R. J. Knecht p.375 [2]

- ^ a b Orientalism in early Modern France 2008 Ina Baghdiantz McAbe, p.71ff, ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0

- ^ Fortress of the soul: violence, metaphysics, and material life by Neil Kamil p.133 [3]

- ^ Ceremonies of possession in Europe's conquest of the New World, 1492–1640 by Patricia Seed p.48 [4]

- ^ From a watery grave by James E. Bruseth

- ^ The Cambridge history of the native peoples of the Americas p.110

- ^ a b c d Decentring the Renaissance by Germaine Warkentin p.103ff

- ^ a b c A new world of animals Miguel de Asúa, Roger French p.148

- ^ The influence of sea power upon history, 1660–1783 Alfred Thayer Mahan p.230 [5]

- ^ Samuel Flagg Bemis, Jay's Treaty: A Study in Commerce and Diplomacy (1923)

- ^ Bradford Perkins, The First Rapprochement: England and the United States, 1795–1805 (1955).

- ^ Alexander De Conde, The quasi-war: the politics and diplomacy of the undeclared war with France 1797–1801 (1996).

Further reading

- Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766 (2007).

- Blumenthal, Henry. France and the United States; Their Diplomatic Relation, 1789–1914 (1970).

- Boucher, Philip P. France and the American Tropics to 1700: Tropics of Discontent? (2007).

- Brazeau, Brian. Writing a new France, 1604–1632: empire and early modern French identity (2009).

- Dickason, Olive Patricia. The Myth of the Savage: and the Beginnings of French Colonialism in the Americas (1984).

- Eccles, W. J. The Canadian Frontier, 1534–1760 (1983).

- Eccles, W. J. France in America (1990).

- Moogk, Peter N. La Nouvelle France: the making of French Canada: a cultural history (2000).

- Roberts, Walter Adolphe. The French in the West Indies (1971).