Brother Andrea Pozzo, S.J. | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait (17th century) | |

| Born | 30 November 1642 |

| Died | 31 August 1709 (aged 66) Vienna, Habsburg monarchy, Holy Roman Empire |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Palma il Giovane, Andrea Sacchi |

| Known for | Architecture, painting, decorator |

| Notable work |

|

Andrea Pozzo (Italian: [anˈdrɛːa ˈpottso]; Latinized version: Andreas Puteus; 30 November 1642 – 31 August 1709) was an Italian Jesuit brother, Baroque painter, architect, decorator, stage designer, and art theoretician.

Pozzo was best known for his grandiose frescoes using the technique of quadratura to create an illusion of three-dimensional space on flat surfaces. His masterpiece is the nave ceiling of the Church of Sant'Ignazio in Rome. Through his techniques, he became one of the most noteworthy figures of the Baroque period. He is also noted for the architectural plans of Ljubljana Cathedral (1700), inspired by the designs of the Jesuit churches Il Gesù and S. Ignazio in Rome.

Biography

Early years

Born in Trento (then under Austrian rule), he studied Humanities at the local Jesuit High School. Showing artistic inclinations he was sent by his father to work with an artist; Pozzo was then 17 years old (in 1659). Judging by aspects of his early style this initial artistic training came probably from Palma il Giovane. After three years he came under the guidance of another unidentified painter from the workshop of Andrea Sacchi who appears to have taught him the techniques of Roman High Baroque. He would later travel to Como and Milan.

As a Jesuit

On 25 December 1665, he entered the Jesuit Order as a lay brother.[1] In 1668, he was assigned to the Casa Professa of San Fidele in Milan, where his festival decorations in honour of Francis Borgia recently canonised (1671) met general approval. He continued artistic training in Genoa and Venice. His early paintings attest the influence of the Lombard School: rich colour, and graphic chiaroscuro. When he painted in Genoa the Life of Jesus for the Congregazione de' Mercanti, he was undoubtedly inspired by Peter Paul Rubens.[citation needed]

Early church decoration

Pozzo's artistic activity was related to the Jesuit Order's enormous artistic needs; many Jesuit churches had been built in recent decades and were devoid of painted decoration. He was frequently employed by the Jesuits to decorate churches and buildings such as their churches of Modena, Bologna and Arezzo. In 1676, he decorated the interior of San Francis Xavier church in Mondovì. In this church one can already see his later illusionistic techniques: fake gilding, bronze-coloured statues, marbled columns and a trompe-l'œil dome on a flat ceiling, peopled with foreshortened figures in architectural settings. This was his first large fresco.

In Turin (1678) Pozzo painted the ceiling of the Jesuit church of SS. Martiri. The frescoes gradually deteriorated through water infiltration. They were replaced in 1844 by new paintings by Luigi Vacca. Only fragments of the original frescoes survive.

Call to Rome

In 1681, Pozzo was called to Rome by Giovanni Paolo Oliva, Superior General of the Jesuits. Among others, Pozzo worked for Livio Odescalchi, the powerful nephew of the pope, Innocent XI.[2] Initially he was used as a stage designer for biblical pageants, but his illusionistic paintings in perspective for these stages soon gave him a reputation as a virtuoso in wall and ceiling decorations.

The Gesù rooms

His first Roman frescoes were in the corridor linking the Church of the Gesù to the rooms where St. Ignatius had lived. His trompe-l'œil architecture and paintings depicting the Saint's life for the Camere di San Ignazio (1681–1686), blended well with already existing paintings by Giacomo Borgognone.

The St Ignatius' Church

His masterpiece, the illusory perspectives in frescoes of the dome,[3] the apse and the ceiling of Rome's Jesuit church of Sant'Ignazio were painted between 1685–1694 and are emblematic of the dramatic conceits of High Roman Baroque. Pozzo was an unrivalled master of perspective; he used light, colour, and an architectural background as means of creating illusion. For several generations, Sant'ignazio set the standard for the decoration of Late Baroque ceiling frescos throughout Catholic Europe. Compare this work to Gaulli's masterpiece in the other major Jesuit church in Rome, Il Gesù.

The church of Sant'Ignazio had remained unfinished with bare ceilings even after its consecration in 1642. Disputes with the original donors, the Ludovisi, had prevented the completion of the planned dome. Pozzo proposed to resolve this by creating the illusion of a dome, when viewed from inside, by painting on canvas. It was impressive to viewers, but controversial; some feared the canvas would soon darken.

On the flat ceiling he painted an allegory of the Apotheosis of S. Ignatius, in breathtaking perspective. The painting, 17 m in diameter, is devised to make an observer, looking from a spot marked by a metal plate set into the floor of the nave,[4] seem to see a lofty vaulted roof decorated by statues, while in fact the ceiling is flat. The painting celebrates the apostolic goals of Jesuit missionaries, eager to expand the reach of Roman Catholicism in other continents. The Counter-Reformation also encouraged a militant Catholicism. For example, rather than placing the usual evangelists or scholarly pillars of doctrine in the pendentives, Pozzo depicted the victorious warriors of the old testament: Judith and Holofernes; David and Goliath; Jael and Sisera; and Samson and the Philistines.

By the skilful use of linear perspective, light, and shade, he made the great barrel-vault of the nave of the church into an idealized aula from which is seen the reception of St. Ignatius into the opened heavens.[1] Light comes from God the Father to the Son who transmits it to St. Ignatius, whence it breaks into four rays leading to the four continents. Pozzo explained that he illustrated the words of Christ in Luke: I am come to send fire on the earth, and the words of Ignatius: Go and set everything aflame. A further ray illuminates the name of Jesus. The attention to movement within a large canvas with deep perspective in the scene, including a heavenly assembly whirling above, and the presence space-enlarging illusory architecture offered an example which was copied in several Italian, Austrian, German and Central European churches of the Jesuit order.

The architecture of the trompe-l'œil dome seems to erase and raise the ceiling with such a realistic impression that it is difficult to distinguish what is real or not. Andrea Pozzo painted this ceiling and trompe-l'oeil dome on a canvas, 17 m wide. The paintings in the apse depict scenes from the life of St. Ignatius, St Francis Xavier and St Francis Borgia.

St Ignatius chapel (Gesù)

In 1695 he was given the prestigious commission, after winning a competition against Sebastiano Cipriani and Giovanni Battista Origone, for an altar in the St. Ignatius chapel in the left transept of the Church of the Gesù.[1] This grandiose altar above the tomb of the saint, built with rare marbles and precious metals, shows the Trinity, while four lapis lazuli columns (these are now copies) enclose the colossal statue of the saint by Pierre Legros. It was the coordinated work of more than 100 sculptors and craftsmen, among them Pierre Legros, Bernardino Ludovisi, Il Lorenzone and Jean-Baptiste Théodon. Andrea Pozzo also designed the altar in the Chapel of St Francesco Borgia in the same church.

Altars in St Ignatius church

In 1697 he was asked to build similar Baroque altars with scenes from the life of St Ignatius in the apse of the Sant'Ignazio church in Rome. These altars house the relics of St. Aloysius Gonzaga and of St. John Berchmans.

Other works of art

Meanwhile he continued painting frescoes and illusory domes in Turin, Mondovì, Modena, Montepulciano and Arezzo. In 1681 he was asked by Cosimo III de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany to paint his self-portrait for the ducal collection (now in the Uffizi in Florence). This oil on canvas has become a most original self-portrait. It shows the painter in a diagonal pose, showing with his right index finger his illusionist easel painting (a trompe-l'œil dome, perhaps of the Badia church in Arezzo) while his left hand rests on three books (probably alluding to his not-yet published treatises on perspective). The painting was sent to the duke in 1688. He also painted scenes from the life of St Stanislaus Kostka in the saint's rooms of the Jesuit novitiate of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale in Rome. He also painted the high altar painting of the Parish Church of Saint Michael in Brixen (known for its White Tower) which depicts Michael’s fight with Lucifer. In 1699 he delivered the plans for the Jesuit Collegium Ragusinum in the Republic of Ragusa, now Dubrovnik.[5]

In 1702 Pozzo painted a cupola on canvas for the Badia delle Sante Flora e Lucilla in Arezzo.

In Vienna

In 1694 Andrea Pozzo had explained his illusory techniques in a letter to Anton Florian, Prince of Liechtenstein and ambassador of Emperor Leopold I to the Papal Court in Rome. Recommended by Prince Liechtenstein to the emperor, Andrea Pozzo, on the invitation of Leopold I, moved in 1702 (1703?) to Vienna. There he worked for the sovereign, the court, Prince Johann Adam von Liechtenstein, and various religious orders and churches, such as the frescoes and the trompe-l'œil dome in the Jesuit Church. Some of his tasks were of a decorative, occasional character (church and theatre scenery), and these were soon destroyed.

His most significant surviving work in Vienna is the monumental ceiling fresco of the Hercules Hall of the Liechtenstein garden palace (1707),[6] an Admittance of Hercules to Olympus, which, according to the sources, was very admired by contemporaries. Through illusionistic effects, the architectural painting starts unfolding at the border of the ceiling, while the ceiling seems to open up into a heavenly realm filled with Olympian gods.

Some of his Viennese altarpieces have also survived (Vienna's Jesuit church). His compositions of altarpieces and illusory ceiling frescoes had a strong influence on the Baroque art in Vienna. He also had many followers in Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia and Poland. His canvases show him to be a far less compelling a painter at close inspection.

Death

Pozzo died in Vienna in 1709[6] at a moment when he intended to return to Italy to design a new Jesuit church in Venice. He was buried with great honours in one of his best realisations, the Jesuit church in Vienna. Agostino Collaceroni was also a pupil.

Family

Pozzo's brother, Giuseppe Pozzo, a Discalced Carmelite friar in Venice, was also a painter. He decorated the high altar of the church of the Scalzi in that city during the last years of the 17th century.[7]

Writing and architecture

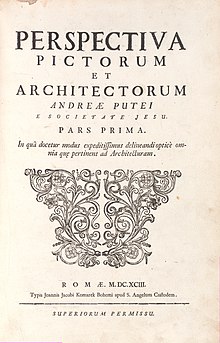

Pozzo published his artistic ideas in a noted theoretical work, entitled Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum (2 volumes, 1693, 1698) illustrated with 118 engravings, dedicated to emperor Leopold I. In it he offered instruction in painting architectural perspectives and stage-sets. The work was one of the earliest manuals on perspective for artists and architects and went into many editions, even into the 19th century, and has been translated from the original Latin and Italian into numerous languages such as French, German, English and, Chinese thanks to Pozzo's Jesuit connection.[8]

There are a few architectural designs in Pozzo's book Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum, indicating that he did not make any designs before 1690. These designs were not realized, but the design for the S. Apollinare church in Rome was used for the Jesuit church of San Francesco Saverio (1700–1702) in Trento. The interior of this church was equally designed by Pozzo.

Between 1701 and 1702, Pozzo designed the Jesuit churches of San Bernardo and Chiesa del Gesù in Montepulciano, but his plans for the last church were only partly realized.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Gietmann, G. (1911). Andreas Pozzo. The Catholic Encyclopedia New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved November 15, 2022

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Fuhring, Peter. Design into Art, Drawings for Architecture and Ornament: The Lodewijk Houthakker Collection, 1898, p.268

- ^ "Andrea Pozzo". www.insecula.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 775. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- ^ Katarina Horvat-Levaj; Mirjana Repanić-Braun (2021). "Jesuit Church of St Ignatius, college and Jesuit stairs, Dubrovnik". Discover Baroque Art - Museum With No Frontiers.

- ^ a b Leader, Anne. "This Day in History: August 31", Italian Art Society

- ^ Bryan, Michael (1889). Walter Armstrong; Robert Edmund Graves (eds.). Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, Biographical and Critical. Vol. II L-Z. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 318.

- ^ Pozzo, Andrea (1724–1732). "Rules and examples of perspective proper for painters and architects, etc". J Senex and R Gosling. Retrieved 2018-08-06.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Andreas Pozzo". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Andreas Pozzo". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Further reading

- Burda-Stengel, Felix (2001). Andrea Pozzo und die Videokunst. Neue Überlegungen zum barocken Illusionismus. Gebrüder Mann Verlag, Berlin (in German) ISBN 3-7861-2386-1

- Burda Stengel, Felix (2006). Andrea Pozzo et l'art video. Déplacement et point de vue du spectateur dans l'art baroque at l'art contemporain. Préface de Hans Belting. isthme editions, editions sept pour la présente edition, Paris (in French) ISBN 2912688655

- Burda-Stengel, Felix (2013). Andrea Pozzo and Video Art. Saint Joseph's University Press, Philadelphia (in English) ISBN 978-0-916101-78-7

- Pozzo, Andrea (1989). Perspective in architecture and painting : an unabridged reprint of the English-and-Latin edition of the 1693 'Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum'. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-25855-6.

- Levy, Evonne Anita (1993). A canonical work of an uncanonical era : re-reading the chapel of Saint Ignatius (1695–1699) in the Gesù of Rome. Thesis (Ph.D.). Princeton University.

- Bösel, R. (1992). "L'architettura sacra di Pozzo a Vienna". In Battisti, Alberta (ed.). Andrea Pozzo. Convegno internazionale Andrea Pozzo e il suo tempo. Milano. pp. 161–176.

- Bénézit, Emmanuel (1976). Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs (10 vol.) (in French). Paris: Librairie Gründ. ISBN 2-7000-0156-7.

- Waterhouse, Ellis Kirkham (1937). Baroque Painting in Rome: The Seventeenth Century. Macmillan & Co. ltd.

- De Feo, Vittorio; Martinelli, Valentino (1996). Andrea Pozzo. Electa. ISBN 88-435-4225-7.

- Carboneri, Nino (1961). Andrea Pozzo, architetto (1642–1709) (in Italian). Trento: Arti grafiche Saturnia.

- Turner, Jane (1990). Grove Dictionary of Art. MacMilllan Publishers Ltd. ISBN 1-884446-00-0.

- Haskell, Francis (1980). Patrons and Painters; Art and Society in Baroque Italy. Yale University Press. pp. 88–92. ISBN 0-300-02540-8.

External links

- Bösel, Richard; Salviucci Insolera, Lydia (2016). "POZZO, Andrea". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 85: Ponzone–Quercia (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- National Gallery, Washington: Biographical details. Preparatory drawing for the ceiling of San Ignazio in the collection.

- Web Gallery of Art: Brief biography

- Pozzo Archived 2007-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Andrea Pozzo frescoes

- Chris Nyborg, Sant'Ignazio di Loyola a Campo Marzio The illusionistic dome seen from the desired position.

- Liechtenstein Garden Palace in Vienna

- Artisti Italian in Austria (in German)

- Perspectiva pictorum atque architectorum (1709)

- Italian Baroque painters

- Italian Baroque architects

- 1642 births

- 1709 deaths

- People from Trento

- 17th-century Italian Jesuits

- 18th-century Italian Jesuits

- Roman Catholic religious brothers

- 17th-century Italian painters

- Italian male painters

- 18th-century Italian painters

- Italian decorators

- Burials at the Jesuit Church, Vienna

- Trompe-l'œil artists

- Catholic painters

- Catholic decorative artists

- 18th-century Italian male artists