| Baldwin V | |

|---|---|

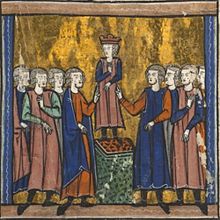

Homage to Baldwin V (crowned, centre) | |

| King of Jerusalem | |

| Reign | 1183 – 1186 |

| Coronation | 20 November 1183 |

| Predecessor | Baldwin IV |

| Successors | Sibylla and Guy |

| Co-king | Baldwin IV (1183–1185) |

| Regent | Raymond III, Count of Tripoli (1185–1186) |

| Born | December 1177 or January 1178 |

| Died | Between May and September 1186 Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem |

| Burial | |

| House | Aleramici |

| Father | William of Montferrat |

| Mother | Sibylla of Jerusalem |

Baldwin V (1177 or 1178 – 1186) was the king of Jerusalem who reigned together with his uncle Baldwin IV from 1183 to 1185 and, after his uncle's death, as the sole king from 1185 to his own death in 1186. Baldwin IV's leprosy meant that he could not have children, and so he spent his reign grooming various relatives to succeed him. Finally his nephew was chosen, and Baldwin IV had him crowned as co-king in order to sideline the child's unpopular stepfather, Guy of Lusignan. When Baldwin IV died, Count Raymond III of Tripoli assumed government on behalf of the child king. Baldwin V died of unknown causes and was succeeded by his mother, Sibylla, who then made Guy king.

Background

Baldwin of Montferrat was born in December 1177 or January 1178 to Sibylla, sister of King Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, after whom he was named.[1] His father, William of Montferrat, had died in June 1177.[1] Though only 16, the king was not expected to live long, nor could he marry and have children, because he had contracted leprosy and was growing weaker.[2][3] Baldwin had thus been expected to succeed his uncle. By July 1178, the king recognized his sister as his new heir presumptive.[1] Her son, Baldwin of Montferrat, followed her in the line of succession.[4]

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, a Crusader state in the Levant ruled by Catholic Franks,[5] was often threatened by the neighbouring Muslim powers.[6] Because of the king's illness, it was imperative that the young Baldwin's mother, Sibylla, remarry soon;[7] she married Guy of Lusignan in early 1180[8] and had four daughters with him.[9] Baldwin IV initially intended Guy to become the next king,[10] but soon realized that Guy was a poor candidate because of his unpopularity with the barons of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and rulers of the neighbouring Crusader states, Prince Bohemond III of Antioch and Count Raymond III of Tripoli.[11]

Kingship

In 1183, King Baldwin IV summoned a council to discuss who could succeed him as king instead of his brother-in-law, Guy.[12] The supporters of the king's sister, Sibylla, were not present, while his younger half-sister, Isabella, and Isabella's husband, Humphrey IV of Toron, were not viable candidates as they were besieged in Kerak by the Egyptian ruler Saladin. Agnes of Courtenay, mother of Sibylla and Baldwin IV, suggested that the young Baldwin, son of Sibylla, should be made co-king with Baldwin IV. Agnes may have acted to foil the ambitions of Raymond of Tripoli, who also had a claim to the throne. As the boy had the next best claim after his mother, his grandmother's proposal was widely accepted. Baldwin V was acclaimed, crowned and anointed in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre on 20 November 1183, and he received homage from all the barons except his stepfather, Guy.[12]

Roger de Moulins and Arnold of Torroja, grand masters of the Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar respectively, and the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, Heraclius, travelled to Western Europe in mid-1184 to seek military aid in defense of the kingdom against potential Muslim attacks.[13] It became apparent in late 1184 or early 1185 that Baldwin IV was dying. He summoned the High Court to select a regent for his nephew.[14] Both the king and the barons wanted to prevent Guy from ruling in the boy's name.[15] They appointed Raymond, but made Joscelin of Courtenay the child's guardian.[16] Baldwin V suffered from ill health,[17] and the contemporary chronicler Ernoul states that Raymond insisted on not having custody of the king so that he would not be blamed if the child died; the historian Bernard Hamilton doubts that the custody arrangement was Raymond's idea.[18] Joscelin was Baldwin V's granduncle with no claim to the throne and had a vested interest in keeping the boy alive. On the other hand, the High Court suspected that Raymond might seek to make himself king and imposed limits on his power to ensure that he could not usurp the royal dignity.[18]

After the question of regency was settled, Baldwin V and Raymond received homage as king and regent, respectively. The young king then took part in a solemn crown-wearing ceremony in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at his uncle's command.[19] From there the boy was carried to banquet on the shoulders of Balian of Ibelin "because he was the tallest of the great lords present";[20] in reality, Balian was chosen to carry the young king because he was a staunch opponent of Guy and the stepfather of Baldwin IV and Sibylla's half-sister, Isabella, the only other possible contender for the throne. Balian's gesture thus signified Isabella's family's support of the boy king.[20] Baldwin IV had died by 16 May 1185, leaving Baldwin V as the sole monarch.[21]

The kingdom faced no external threats during Baldwin V's reign, as Raymond succeeded in procuring a truce from Saladin.[22] Western princes refused to come to aid, likely because they could not be offered the crown but, at most, the prospect of a temporary rule on behalf of a minor.[23] Only the king's paternal grandfather, experienced crusader Marquess William V of Montferrat, moved to the East, ensuring that the child's rights would be upheld.[23][24] Though the failure of the mission to Europe secured his regency, Raymond could not exercise much power; key government posts were occupied by the supporters of Guy, who continued to resent not being regent for his stepson.[25]

Death and aftermath

Baldwin V died of unknown causes in Acre between May and mid-September 1186.[27] The exact date is not known;[27] the historian Steven Runciman proposes late August.[28] The contemporary chronicler William of Newburgh wrote that Baldwin was poisoned by his regent, Raymond of Tripoli, but William was generally hostile to the count. Hamilton considers foul play by Raymond unlikely because the king was in the care of his granduncle Joscelin of Courtenay.[27]

Baldwin V's death led to another crisis. Joscelin handed his body to the Templars, who took it to Jerusalem for funeral. Raymond did not attend the funeral–historian Malcolm Barber argues that he was mustering supporters to claim the throne–but Joscelin, Reginald of Châtillon, Patriarch Heraclius, Baldwin's grandfather William, and the masters of the military orders were present.[29] Baldwin became the seventh and last of the Latin kings to be buried in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[27] Baldwin's mother, Sibylla, promptly established herself as the successor to her son[30] and then invested her husband, Guy, with kingship.[31] Jerusalem was conquered by Saladin in 1187. Baldwin's mother and half-sisters died in 1190, leaving his half-aunt, Isabella I, as the heir to what remained of the kingdom.[32] Baldwin V's elaborate tomb, likely commissioned by Sibylla, survived until 1808 when it was destroyed in a fire.[27]

References

- ^ a b c Hamilton 2000, p. 139.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 109.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 411.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 148.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 54.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 140.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, pp. 150–158.

- ^ Hamilton 1978, p. 172.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 188.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, pp. 158, 194.

- ^ a b Hamilton 2000, p. 194.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 201.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 205.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, pp. 195, 205.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 443.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1973, p. 107.

- ^ a b Hamilton 2000, p. 206.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, pp. 207, 208.

- ^ a b Hamilton 2000, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 210.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 211.

- ^ a b Hamilton 2000, p. 214.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 444.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 215.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, pp. xviii, xxi.

- ^ a b c d e Hamilton 2000, p. 216.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 446.

- ^ Barber 2012, p. 293.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 218.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, p. 220.

- ^ Hamilton 2000, pp. 230–232.

Sources

- Barber, Malcolm (2012). The Crusader States. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300189315.

- Hamilton, Bernard (1978). "Women in the Crusader States: The Queens of Jerusalem". In Baker, Derek (ed.). Medieval Women. Ecclesiastical History Society. ISBN 978-0631192602.

- Hamilton, Bernard (2000). The Leper King and His Heirs: Baldwin IV and the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64187-6.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1973). The feudal nobility and the kingdom of Jerusalem, 1147–1277. Macmillan.

- Runciman, Steven (1952). A History of the Crusades: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0241298768.