Carel Vosmaer (20 March 1826 – 12 June 1888) was a Dutch poet and art critic, born in The Hague. He wrote under the pseudonym Flanor.

Life

He studied law at the University of Leiden, obtaining a degree in 1851, and was for many years Deputy Recorder to the High Court of Justice in his native town, "an office he resigned in 1873, in order to devote himself wholly to art and letters."[1] His first volume of poems, 1860, did not contain much that was remarkable. It was not until after the sensational appearance of Multatuli (pen name of Edward Douwes-Dekker) that Vosmaer, at the age of forty, woke up to a consciousness of his own talent. In 1869 he produced an exhaustive monograph on Rembrandt, which was issued in French.[2]

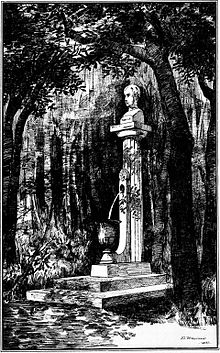

Vosmaer became a contributor to, and then the leading spirit and editor of, a journal which played an immense part in the awakening of Dutch literature; this was the Nederlandsche Spectator, in which a great many of his own works, in prose and verse, originally appeared. The remarkable miscellanies of Vosmaer, called Birds of Diverse Plumage, appeared in three volumes, in 1872, 1874 and 1876. In 1879 he selected from these all the pieces in verse, and added other poems to them. In 1881 he published an archaeological novel called Amazone, described as an "art-novel", the scene of which was laid in Naples and Rome, and which described the raptures of a Dutch antiquary in love.[3] The sculptor Aktol, with his studio in the Baths of Diocletian, is based on Moses Jacob Ezekiel. It was translated into French, German, Belarusian, and an English translation was published in 1884.[4]

Vosmaer undertook the gigantic task of translating Homer into Dutch hexameters, and he lived just long enough to see this completed and revised. In 1873 he went to London to visit his lifelong friend, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and on his return published Londinias, an exceedingly brilliant mock-heroic poem in hexameters. His last poem was Nanno, an idyll on the Greek model. Vosmaer died in Montreux, Switzerland, on 12 June 1888.[5]

Evaluation

He was unique in his fine sense of plastic expression; he was eminently tasteful, lettered, and relined. Without being a genius, he possessed immense talent, just of the order to be useful in combating the worn-out rhetoric of Dutch poetry. His verse was modelled on Heine and still more on the Greeks; it is sober, without colour, stately and a little cold. He was a curious student in versification, and it is due to him that hexameters were introduced, and the sonnet reintroduced, into the Netherlands. He was the first to repudiate the traditional, wooden alexandrine. In prose he was greatly influenced by Multatuli, in praise of whom he wrote an eloquent treatise, Een Zaaier (A Sower). He was also somewhat under the influence of English prose models.[5]

References

- ^ Irving, E. J. (1884). "Introductory Note". The Amazon. New York: T. F. Unwin. p. ix.

- ^ Gosse 1911, p. 214.

- ^ Gosse 1911, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Vosmaer, Carl (1884). The Amazon. New York: T. F. Unwin.

- ^ a b Gosse 1911, p. 215.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gosse, Edmund (1911). "Vosmaer, Carel". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 214–215.