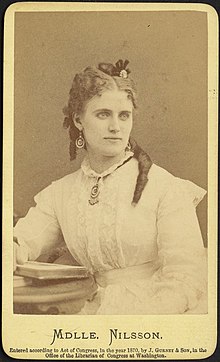

Christine Nilsson | |

|---|---|

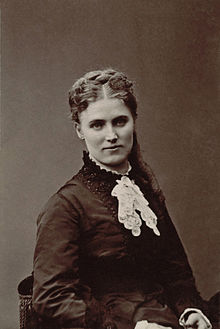

Nilsson in 1870 | |

| Born | Christina Jonasdotter 20 August 1843 near Växjö, Småland, Sweden |

| Died | 22 November 1921 (aged 78) |

| Occupation | opera singer |

Christina Nilsson, Countess de Casa Miranda, also called Christine Nilsson[1] (20 August 1843 – 22 November 1921)[2] was a Swedish operatic dramatic coloratura soprano. Possessed of a pure and brilliant voice (B3-F6), first three then two and a half octaves trained in the bel canto technique, and noted for her graceful appearance and stage presence,[3][4][5] she enjoyed a twenty-year career as a top-rank international singer before her 1888 retirement.[3] A contemporary of one of the Victorian era's most famous divas, Adelina Patti,[6] the two were often compared by reviewers and audiences, and were sometimes believed to be rivals.[4][7] Nilsson became a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music in 1869.

Biography

Christina Nilsson was born Christina Jonasdotter in a forester's hut[8] at Sjöabol (or Snugge) farm[9][10] near Växjö, Småland, the youngest of seven children of the peasants Jonas Nilsson (1798 - 1871) and Stina Cajsa Månsdotter (1804 - 1870).[11] As a young child she received a rudimentary education, attending the local village free school where she learnt to read and write.[12] From her earliest years, she demonstrated musical talent, both singing and in playing the violin and flute, and she was taught some music basics by Sven Grankvist, the parish organist, who unsuccessfully attempted to persuade her to go to Stockholm in search of further musical training.[13][14] The family was very poor,[15] making such training out of the question, and to make extra money the young Christina would sometimes go to the local market fairs with her parents or brother to perform.[15][16] At the age of eleven, she was described in the Stockholm newspaper Fäderneslandet.[11] She was discovered at age 14 by a wealthy district judge Fredrik Tornérhjelm[11] when she was performing at such a market in Ljungby.[17] Tornérhjelm became her patron, enabling her to take vocal training with Mlle Adelaide Valerius, Baronne de Leuhusen in Halmstad between 1857 and 1858. The Czech composer Bedřich Smetana, who lived in Gothenburg, became her piano teacher between 1858 and 1859.[12][17][11] Upon request from Adelaide de Leuhusen, she went to Stockholm in September 1859, where she became a student of Franz Berwald, who gave her singing and violin lessons, and taught her music theory; Hilda Thegerström, another pupil of Berwald, was engaged at the same time to give the young Christina piano lessons, while Berwald's wife Mathilde gave her French and German language lessons.[5][18]

In 1860, Nilsson gave her professional debut in concerts in Stockholm and Uppsala, receiving mixed reviews.[18][19] It was then decided that she should seek further training in Paris. Adelaide de Leuhusen's sister, the artist Bertha Valerius, was planning a trip there anyway, and would be able to act as a chaperone while Nilsson got settled in.[20] In Paris, Nilsson initially stayed in Madame Crespy's pension, before transferring to Clara Collinet's school in Batignolles, where she stayed for three years. She studied for a year with Jean Jacques Masset, a retired tenor who had become a prominent voice teacher. He professed himself very pleased with Nilsson's voice and progress. Adelaide de Leuhusen disagreed, believing Masset was too lenient and was spoiling Nilsson. She may also have been concerned his training would damage Nilsson's voice.[21] In the autumn of 1861, therefore, Adelaide de Leuhusen transferred Nilsson to Pierre François Wartel, who had been a student of the famous singer Adolphe Nourrit.[21] Nilsson would study with him for three years.[11]

This period gave her the opportunity to build relationships with the Parisian musical world. Meyerbeer, having heard her as a student, was impressed with her voice, and offered her the role of "Ines" in his opera L'Africaine as a debut. Nilsson instead accepted a contract from a Brussels-based impresario to appear in Italian operas. This came to nothing, after the impresario went bankrupt, leaving Nilsson free in 1864 to accept an offer from Caroline Miolan-Carvalho and her husband Léon Carvalho, prima donna and manager respectively of the Théâtre Lyrique, Paris.[22][23][24] Nilsson's operatic début that year as "Violetta" in Giuseppe Verdi's opera La Traviata at the Théâtre Lyrique was a splendid success, despite Nilsson being unknown to the public[13][23] and she became a leading member of the company there until 1867, appearing alongside Miolan-Carvalho in operas such as Mozart's Magic Flute and Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots; other roles included "Henrietta" in Flotow's Martha and "Donna Elvira" in Mozart's opera Don Giovanni.[11] She then made her London debut in June 1867 at Her Majesty's Theatre, again as "Violetta", and appeared there as "Marguerite" in Gounod's Faust in the same year, Miolan-Carvalho (who had created the role of "Marguerite" in 1859) travelling specially to London to hear the performance.[23][22] Other London performances included the title role in Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor (May 1868) and "Cherubino" in Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro (June 1868).[11]

In 1868, Nilsson transferred from the Théâtre Lyrique to the Paris Opera, where she created the role of "Ophelia" in Ambroise Thomas's Hamlet.[5] This was followed in 1869 by the Paris Opera's first production of Faust.[5] This last created a stir in Paris. The opera was part of the Théâtre Lyrique's repertory, restricting performances at other Parisian opera houses, and Miolan-Carvalho, the prima donna of the Théâtre Lyrique and the creator of the role of "Marguerite", had monopolised the role. In 1868, however, the Théâtre Lyrique went bankrupt, the Paris Opera acquired the rights to perform Faust, and Miolan-Carvalho signed a contract to join the Paris Opera. Despite expectations that Miolan-Carvalho would sing 'her' role of "Marguerite" in her new opera house, the role was given to Nilsson. The decision was controversial, and reviews of the time focused on the differences between the two singers. Despite mixed reviews, Nilsson would perform the role frequently across the rest of her career.[3]

Nilsson made her debut at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in 1869 in Lucia di Lammermoor, and also sang the first London performance of Hamlet. Further London performances between 1869 and 1874, Nilsson dividing her time between Covent Garden, Drury Lane, and Her Majesty's Theatre, and singing work by artists as varied as Mozart, Meyerbeer, Ambroise Thomas, Wagner, Verdi, and Michael Balfe.[5]

Her North American operatic debut took place in Boston in October 1871, when she once again portrayed "Marguerite" in Gounod's Faust. This was followed by her first operatic performance in New York City at the Academy of Music in 1871, singing in the first New York performance of Thomas's Mignon. During 1871–1873 she also appeared in opera performances in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Washington DC. New roles included "Zerlina" in Mozart's Don Giovanni and "Leonora" in Verdi's Il Trovatore both in New York.[2][5][11]

Nilsson also made concert tours: a tour of the United States and Canada in autumn 1870 (with Maurice Strakosch as manager), with her first concert at Steinway Hall, New York, in September; and several times of Russia between 1872 and 1875.[5] The North American tour proved extremely lucrative, reportedly netting her two hundred thousand dollars and the acclaim of the American public.[22] After her first successful US tour Nilsson returned to England and married the French stockbroker Auguste Rouzaud (b.1837) The wedding in Westminster Abbey, London, on July 27, 1872, was boycotted by the groom's family. The marriage lasted until February 1882 when Rouzaud died in Paris after a period of illness.[11]

Composer Piotr Tchaikovsky heard Nilsson's interpretation of "Marguerite" in Faust at her Moscow debut in November 1872, and claimed she embodied Goethe's ideals. Her performances in Russia were well received by audiences, including the Tsar and Tsarina, who gifted her valuable jewelry (now on display at Smålands Museum in Växjö).[11]

In 1876, Nilsson undertook a Scandinavian tour. On August 25, she portrayed "Marguerite" in a performance of Faust at the Royal Stora Theatre, Stockholm, and she also performed the roles of "Valentine" (in Les Huguenots) and "Mignon". She also sang in Uppsala, Kristiania (Oslo), Gothenburg, Växjö, Malmö and Copenhagen. This was followed by a debut in January 1877 at the Hofoper in Vienna in the role of "Ophelia", after which she was appointed Imperial Austro-Hungarian Court and Chamber Singer. She also performed in Budapest, Hamburg and Brussels, before returning to London for another opera season. In the autumn of 1877 she traveled again to Russia and here she was appointed Imperial Russian Chamber Singer.[11]

Christina Nilsson made her Spanish opera debut with "Marguerite" in Faust at the Teatro Real in Madrid in 1879. In the summer of 1880, she presented the double roles of "Margherita" and "Helen of Troy" in Arrigo Boito's opera Mefistofele for the first time at performances at Her Majesty's Theatre in London. In the autumn of 1881, she sang in Stockholm in connection with a royal wedding.[11]

On October 22, 1883, Christina Nilsson sang the role of "Marguerite" in Faust at the inauguration of the Metropolitan Opera House, New York. She then appeared in a number of American and Canadian cities. Later that year, she sang for the President of the United States Chester A. Arthur at the White House. Her final appearances in the United States took place in early June 1884.[11]

In August 1885, she began another tour of Scandinavia. After her third Stockholm concert on 23 September, she gave a performance from the balcony of the Grand Hotel in Stockholm. An estimated 50,000 people gathered to hear the world-famous soprano. A panic broke out and a large number of people died or were injured. Nilsson then continued with her tour, giving further concerts in Scandinavia, Germany, Prague, and Vienna, including her first recital in Berlin (9 November 1885).[11]

In March 1887, Christina Nilsson married Don Angel Ramon Maria Vallejo y Miranda es, Count de Casa Miranda es (b.1832), a Spanish journalist and diplomatic official. The wedding took place in church of La Madeleine, Paris. The pair had been involved in a relationship since 1882, and Casa Miranda's daughter Rosita had accompanied Nilsson on her 1882–1883 trip to the USA. Now she was remarried, Nilsson decided to retire, marking the occasion by giving two farewell performances at the Royal Albert Hall, London, in 1888. Now known as the Countess de Casa Miranda, Nilsson settled in France and Spain.[11]

In 1894, Nilsson published Om röstens utbildning: Några råd till unga sångerskor ("Some advice for young singers"). She also composed two romances for voice and piano, with lyrics by herself, Jag hade en vän and Ophelia's Lament.[11]

In 1902, Nilsson became a widow for the second time. Four years later, she bought Villa Vik outside Växjö, spending her last years there. She died in Växjö in 1921, and is buried there at Tegnérkyrkogården.[11]

Unlike Patti, Nilsson never made gramophone recordings of her voice.[25][26] Though described as of moderate power, Nilsson's voice in her prime was described as of "crystalline brilliancy, resonance, and purity of tone." Perfectly even in its register, when she began singing she could reportedly span three and a half octaves, though after her first three years of stage singing this had diminished to an easy two and a half octaves stretching from a low G natural to a high D. She was particularly popular with English audiences for the "crystalline ethereal quality of her voice", especially in oratorio.[22] Comparisons to Patti were common – it was said Nilsson lacked "the velvet voluptuous sweetness" of Patti's voice, and perhaps too "the perfect mechanism of Patti's vocal art" – but Nilsson's voice was said to possess a poignancy that lent itself best to pathetic characters such as "Marguerite" and "Ophelia", and to have "something strange" about it, "which no one could quite define".[22] One English critic, summing up the two, concluded, "When Patti sings, one fancies the notes of the lark rising to the gates of heaven, but Nilsson's voice is a strain from the other side of the gates."[22]

In literature

She is a minor character in The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton.[27]

She is mentioned in Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy.[28]

She is widely believed to have been the inspiration for Christine Daaé, the heroine of Gaston Leroux's novel The Phantom of the Opera.[29][30] Towards the end of his life, Leroux claimed the character was based on a real opera singer "whose real name I hid under that of Christine Daaé",[30] and details of Nilsson's early life heavily reflect details in the fictitious Christine Daaé's history,[29][30][31] even to the point of using ideas and language from contemporary reviews of Nilsson's performances in Faust in 1869.[32]

In popular culture

Nilsson is a minor character in the first episode of Season 2 of the television series The Gilded Age, and was played by Sarah Joy Miller. [33]

Notes

- ^ "Nilsson, Christine (1843–1921) | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com.

- ^ a b Warrack, John; West, Ewan (1996). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera. Oxford University Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-19-280028-2. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Rowden, Clair (2018). "Deferent Daisies: Caroline Miolan Carvalho, Christine Nilsson and Marguerite, 1869" (PDF). Cambridge Opera Journal. 30 (2–3). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 237–258. doi:10.1017/s0954586719000089. ISSN 0954-5867. S2CID 186985223. [1]

- ^ a b The Literary Lorgnette: Attending Opera in Imperial Russia. Stanford University Press. 2000. ISBN 978-0-8047-3247-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g The Grove Book of Opera Singers. Oxford University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-0-19-533765-5.

- ^ Freitas, Roger (1 August 2018). "Singing Herself: Adelina Patti and the Performance of Femininity". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 71 (2): 287–369. doi:10.1525/jams.2018.71.2.287. Retrieved 19 December 2021 – via online.ucpress.edu.

- ^ "One of the most important and brilliant rivals of Adelina Patti was Christine Nilsson, a Swede."[2]

- ^ The Standard Musical Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive Reference Library for Musicians and Musiclovers. University Society. 1910.

- ^ "Snugge – the birthplace of opera singer Christina Nilsson | Meetings & Events in Växjö". vaxjoco.se. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ Adventure Guide to Sweden. Hunter Publishing. 2006. ISBN 978-1-58843-552-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Christina Nilsson, article by Ingegerd Björklund". Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ a b The Ladies' Treasury and Treasury of Literature. 1870.

- ^ a b Emens, Helen Byington (1896). "Women as Vocalists". In King, William C. (ed.). The World's Progress as Wrought by Men and Women in Art, Literature, Education, Philanthropy, Reform, Inventions, Business and Professional Life. Springfield, Massachusetts: King-Riehardson Publishing Co. pp. 476–478. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ The Compelling: A Performance-oriented Study of the Singer Christina Nilsson. Göteborg University, Department of Musicology. 2001. ISBN 978-91-85974-60-3.

- ^ a b Truth. 1882.

- ^ A Star of Song!: The Life of Christina Nilsson. Press of Wynkoop & Hallenbeck. 1870.

- ^ a b "The Biographical Review of Prominent Men and Women of the Day". Gehman. 1888.

- ^ a b The Compelling: A Performance-oriented Study of the Singer Christina Nilsson. Göteborg University, Department of Musicology. 2001. ISBN 978-91-85974-60-3.

- ^ The Compelling: A Performance-oriented Study of the Singer Christina Nilsson. Göteborg University, Department of Musicology. 2001. ISBN 978-91-85974-60-3.

- ^ Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly. Frank Leslie Publishing House. 1889.

- ^ a b The Compelling: A Performance-oriented Study of the Singer Christina Nilsson. Göteborg University, Department of Musicology. 2001. ISBN 978-91-85974-60-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Great Singers. D. Appleton. 1895.

- ^ a b c Wagner. Rossini. Verdi. Thalberg. Paganini. Adelina Patti. Christine Nilsson. Mario. R. Bentley and son. 1886.

- ^ She was offered a three year contract, beginning with 2,000 francs per month in the first year and rising to 3,000 francs per month by the third year. [3]

- ^ Song on Record: Without special title. Cambridge University Press. 1986. ISBN 978-0-521-36173-6.

- ^ A 1959 historic recordings compilation included a cylinder recording of a Swedish song, recorded c.1897 by an unidentified soprano. At the time it was speculated that the cylinder might be a hitherto unknown recording made by Nilsson. However, no corroborating evidence was ever found, and the identity of the singer remained a mystery. [4]

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg E-text of The Age of Innocence, by Edith Wharton". www.gutenberg.org.

- ^ "Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy". gutenberg.org.

- ^ a b Gifts of Passage: What the Dying Tell Us with the Gifts They Leave Behind. Thomas Nelson. 31 August 2009. ISBN 978-1-4185-7616-5.

- ^ a b c The Phantom of the Opera. OUP Oxford. 8 March 2012. ISBN 978-0-19-969457-0.

- ^ Paris and the Musical: The City of Light on Stage and Screen. Routledge. 17 March 2021. ISBN 978-0-429-87862-6.

- ^ Opera in the Novel from Balzac to Proust. Cambridge University Press. 31 March 2011. ISBN 978-1-139-49585-1.

- ^ "Sarah Joy Miller | Actress". IMDb.

References

- Gustaf Hilleström: Kungl. Musikaliska Akademien, Matrikel 1771–1971 (The Royal Academy of Music 1771–1971) (in Swedish)

- The Compelling: A Performance-Oriented Study of the Singer Christina Nilsson, Ingegerd Björklund, Göteborg, 2001

- Die Goede Oude Tyd, by Anton Pieck and Leonhard Huizinga, Zuid-Hollandsche Uitgeversmaatschappy, Amsterdam, 1980, page 31.

- De Werelde van Anton Pieck, text by Hans Vogelesang, La Rivière & Voorhoeve, Kampen, 1987, page 197.

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Further reading

- Björklund, Ingegerd Christina Nilsson at Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon

- Guy de Charnacé: A star of song! the life of Christina Nilsson

External links

Media related to Christina Nilsson at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Christina Nilsson at Wikimedia Commons