Gabriel Alapetite | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prefect of Indre | |

| In office March 1888 – December 1888 | |

| Prefect of Sarthe | |

| In office 1 December 1888 – 23 May 1889 | |

| Prefect of Puy-de-Dôme | |

| In office May 1889 – January 1890 | |

| Prefect of Pas-de-Calais | |

| In office January 1890 – September 1900 | |

| Prefect of Rhône | |

| In office 1900–1906 | |

| French Resident-General in Tunisia | |

| In office 29 December 1906 – 26 October 1918 | |

| Preceded by | Stephen Pichon |

| Succeeded by | Étienne Flandin |

| French Ambassador to Spain | |

| In office 1918–1920 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Thierry |

| Succeeded by | Charles de Beaupoil |

| Commissioner General in Strasbourg | |

| In office 1920–1924 | |

| Preceded by | Alexandre Millerand |

| Succeeded by | none |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 January 1854 Clamecy, Nièvre, France |

| Died | 22 March 1932 (aged 78) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Civil servant, diplomat |

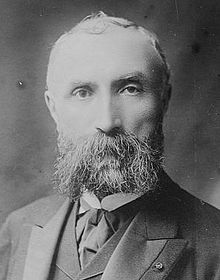

Gabriel Ferdinand Alapetite (5 January 1854 – 22 March 1932) was a French senior civil servant and diplomat. From 1879 to 1906 he was sub-prefect or prefect of various departments of France. For eleven years from 1906 to 1918 he was Resident-General of France in Tunisia, where he initiated various administrative improvements. He considered that the Tunisian Muslims had an utterly different mentality from French people, and could never become citizens of France. He was violently antisemitic, and opposed recruiting Tunisian Jews during World War I (1914–18). After the war he was briefly French Ambassador in Madrid, then for four years administered Alsace-Lorraine, which had been returned from Germany to France.

Early years

[edit]Gabriel Alapetite was born on 5 January 1854 in Clamecy, Nièvre.[1] He came from an old republican family.[2] His parents were Marien Ferdinand Alapetite (1821–95) and Alphonsine Janiska (1832–91). His siblings were Jeanne Marie Alapetite (1852–1918) and Emile Marien Alapetite (1856–1911).[3] Gabriel Alapetite qualified as a lawyer in Paris in 1873.[1] He began practice as a lawyer with Théodore Tenaille-Saligny as his political mentor.[2] Tenaille-Saligny was named Prefect of Pas-de-Calais in 1876, then Prefect of Haute-Garonne, and appointed Alapetite his chef de cabinet.[2] Alapetite was chef de cabinet in Pas-de-Calais from December 1876 to May 1877 and in Haute-Garonne from December 1877 to February 1879.[4]

Administrator in France

[edit]Tenaille-Saligny became a Senator from 1879 to 1888, while Alapetite followed a standard administrative progression. He proved extremely able and advanced rapidly.[2] He was in turn Sub-Prefect of Muret from 25 March 1879, Loudun from 11 November 1880 and Châtellerault from 21 October 1883. He was made Secretary-General of Rhône on 25 April 1885.[4] Alapetite was appointed Prefect of Indre on 20 June 1888.[4] He was only 34 at this time, very young for such a responsible position.[5] He was appointed Prefect of Sarthe on 1 December 1888, then Prefect of Puy-de-Dôme on 24 May 1889.[4] On 3 July 1889 he married Magdeleine Louise Etiennette Tenaille-Saligny (1867–1943), daughter of Theodore Tenaille-Saligny. They had three children, Marguerite (1893–1958), Germaine Louise Alphonsine (1894–1971) and Michel Ferdinand (1896–1982).[3]

Alapetite was appointed Prefect of Pas-de-Calais on 8 January 1890.[4] On 14 September 1894 the miners in the Pas de Calais started a general strike.[6] Gabriel Alapetite acted tactfully but decisively to prevent disturbances, as he had in similar circumstances two years earlier, and only one person died during the strike.[7] He played a balancing act in correcting the initiatives of the Ministry of Public Works, the Ministry of the Interior, the President of the Council and the Ministry of War. He convinced the President of the Council to threaten to withdraw troops from the mining basin, and this persuaded the companies to accept negotiations.[8] As prefect, Alapetite was a faithful ally of the political leader Alexandre Ribot.[9] Alapetite was Prefect of Rhône from 1900 to 1906.

Resident-General in Tunisia

[edit]Alapetite was Resident-General in Tunisia from 1906 to 1918.[1] Shortly after he took up his post, the Tunisian Consultative Conference was expanded to include Muslim and Jewish representatives for the first time.[10] In Tunisia he developed public works, supported colonization and improved finance and education. He created provident funds and developed agricultural cooperation, which reduced scarcity and famine.[11] Alapetite wanted to improve treatment of the mentally ill. He wrote that "the moral conquest of the native through medical welfare is a long-term effort" to advance the interests of France in North Africa.[12] Alapetite inaugurated a monument with a bust of the geologist Philippe Thomas by the sculptor André César Vermare in Sfax on 26 April 1913.[13][14] Thomas had discovered large deposits of phosphates of lime, which had greatly helped the Tunisian economy.[15] Alapetite inaugurated another monument in honour of Thomas in Tunis on 29 May 1913.[16]

During World War I (1914–18) in December 1914 Alapetite wrote that German and Ottoman propaganda was convincing the tirailleurs that "the Commander of Believers forbids them to go and get themselves killed for the infidels."[17] Alapetite was opposed to letting indigenous soldiers return home, either as convalescents or on leave. Sending wounded men home would demoralize their families, and men on leave would exaggerate the dangers and hardships of total warfare in the cold climate of northern France. He did not feel that Tunisians should be treated in the same way as French people, since the Tunisian Muslims had a different mentality. He wrote, "it is dangerous to make of this affair a question of principle or sentiment."[18] Alapetite sent Muslim notaries to assist Tunisian soldiers and help with burial rites, but found it very difficult to find an imam to minister to the soldiers at the front.[19]

Alapetite strongly opposed sending Muslim troops to the Dardanelles during the Gallipoli Campaign, where they would be fighting against Muslims, and this view prevailed. Later, North African troops did fight the Ottomans in the Middle East.[20] In 1915 Alapetite opposed giving Tunisian soldiers French citizenship. He wrote, "in Tunisia, the naturalized French Muslim appears as an uprooted apostate." He said that naturalizing the Muslims would be an indirect annexation and would violate the treaties France had made with the Bey of Tunis.[21] After his retirement Alapetite wrote, "Long experience with Oriental Muslims only allows the European to understand one precise fact about their mentality: that their brain does not reason like ours."[22]

Alapetite was deeply antisemitic, as was typical of the French administration in Tunisia.[23] In the fall of 1916 Pierre Roques, Minister of War, wrote to Alapetite suggesting that as part of the drive to recruit natives troops for 1917 it might be sensible to call Tunisian Jews to arms.[24] Alapetite wrote a long reply in which he rejected the idea. He said that conscripting Tunisian Jews would be equivalent to granting them French citizenship, and this would provoke the Muslims. If Jews were recruited, France would lose proven Muslim troops for the sake of a Jewish force "that all the current data permits us to consider as mediocre in every regard."[24] He saw the Tunisian Jews as clannish, ungenerous, exploitative and even "parasitic." He wrote, "Until the present, political power has escaped the Jews in Tunisia, it is the only force they lack. They know well that if they have it, the enslavement of the Muslim natives won't be long in coming."[24]

Later career

[edit]Gabriel Alapetite was French Ambassador in Madrid from 1918 to 1920.[1]

Alapetite was French Commissioner General in Strasbourg, Alsace-Lorraine, from 1920 to 1924.[1] Alapetite replaced Alexandre Millerand as Commissioner General. As a career bureaucrat he did not have the vision or political skills of his predecessor.[25] He had to deal with labour tensions, disputes over language and religion, difficulties implementing French law and difficulties with Alsatian civil servants. Although Alapetite was willing to make compromises, he could not satisfy the expectations of the Alsatians, and the transfer of powers from his office to the ministries in Paris served to weaken his position.[25]

In 1920 Alapetite stated before a regional consultative assembly that he hoped Alsatians would learn one new French word each day, and forget one German word.[26] Members of the Harvard Glee Club visited Strasbourg on Bastille Day on 14 July 1921. Prompted by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who wanted to impress the foreign visitors, Alapetite arranged for an exhibition of traditional Alsatian dress at Orangerie Park with over 400 participants to "make these seventy American delegates aware of happy Alsace, French Alsace."[27]

Gabriel Alapetite died on 22 March 1932 in Paris aged 78.[1]

Honours

[edit]Alapetite was decorated with the Ordre des Palmes Académiques on 12 July 1884.[4] He was named Knight of the Legion of Honour on 3 August 1890, Officer of the Legion of Honour on 7 January 1894 and Commander of the Legion of Honour on 26 January 1906.[28] Gabriel Alapetite was elected a full member of the Académie des Sciences Coloniales in 1926.[11]

Publications

[edit]- Alapetite, Gabriel (1873), Du payement en général et de l'imputation des payements (Thesis for License in Law), Paris: A. Derenne, p. 76

- Alapetite, Gabriel (1913), Pour le relèvement des indigènes tunisiens : enseignement professionnel, assistance, prévoyance, Tunis

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Alapetite, Gabriel (July–September 1993), "Grève des mineurs et conventions d'Arras (extrait de ses souvenirs", Le Mouvement Social (164): 17–24, doi:10.2307/3779156, JSTOR 3779156

- Henri Hugon (1913), Les Emblèmes des beys de Tunis, étude sur les signes de l'autonomie husseinite, monnaies, sceaux, étendards, armoiries, marques de dignités et de grades, décorations, médailles commémoratives militaires, preface by G. Alapetite, Paris: E. Leroux

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Gabriel Alapetite (1854–1932) – BnF.

- ^ a b c d Michel 1993, p. 10.

- ^ a b Parent.

- ^ a b c d e f Résumé des Services M Apetite.

- ^ Michel 1993, p. 11.

- ^ Burke 1894, p. 329.

- ^ Burke 1894, p. 330.

- ^ Michel 1993, p. 12.

- ^ Schmidt 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Rodd Balek 1920–1921, pp. 358–59.

- ^ a b ALAPETITE Gabriel – Académie...

- ^ Keller 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Académie des sciences 1986, p. 79.

- ^ Philippe Thomas – Le Site Sfaxien.

- ^ Cilleuls 1969, p. 139.

- ^ Cilleuls 1969, p. 140.

- ^ Storm & Al Tuma 2015, p. 32.

- ^ Fogarty 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Storm & Al Tuma 2015, p. 29.

- ^ Storm & Al Tuma 2015, p. 34.

- ^ Lewis 2013, p. 138.

- ^ Keller 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Katz 2015, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Katz 2015, p. 40.

- ^ a b Fischer 2010, p. 134.

- ^ Gordon 1978, p. 99.

- ^ Fischer 2010, p. 171.

- ^ Alapetite – Legion d'Honneur.

Sources

[edit]- Académie des sciences (January 1986), "Homage à Philippe Thomas (1843–1910)", La Vie des Sciences (in French), Paris: Gauthier-Villars, retrieved 2017-09-02

- Alapetite (in French), Legion d'Honneur, retrieved 2017-09-25

- ALAPETITE Gabriel (in French), Académie des sciences d'outre-mer, retrieved 2017-09-25

- Burke, Edmund (1894), The Annual Register, Rivingtons, retrieved 2017-09-25

- Cilleuls, Jean des (1969), A propos des phosphates de Tunisie et de leur découverte par Philippe THOMAS, vétérinaire militaire I1843-1910) (PDF) (in French), retrieved 2017-09-01

- Fischer, Christopher J. (2010), Alsace to the Alsatians?: Visions and Divisions of Alsatian Regionalism, 1870-1939, Berghahn Books, ISBN 978-1-84545-724-2, retrieved 2017-09-26

- Fogarty, Richard S. (2008-07-16), Race and War in France: Colonial Subjects in the French Army, 1914–1918, JHU Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-8824-3, retrieved 2017-09-26

- Gabriel Alapetite (1854–1932) (in French), BnF: Bibliotheque nationale de France, retrieved 2017-09-25

- Gordon, David C. (1978-01-01), The French Language and National Identity (1930–1975), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-080994-7, retrieved 2017-09-26

- Katz, Ethan B. (2015), The Burdens of Brotherhood: Jews and Muslims from North African to France, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-08868-9, retrieved 2017-09-26

- Keller, Richard C. (2008-09-15), Colonial Madness: Psychiatry in French North Africa, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-42977-9, retrieved 2017-09-26

- Lewis, Mary Dewhurst (2013-09-27), Divided Rule: Sovereignty and Empire in French Tunisia, 1881–1938, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-95714-5, retrieved 2017-09-26

- Michel, Joël (July–September 1993), "Ordre public et agitation ouvrière: l'habileté du préfet Alapetite", Le Mouvement Social (in French) (164), Editions l'Atelier on behalf of Association Le Mouvement Social: 7–15, doi:10.2307/3779155, JSTOR 3779155

- Parent, Jean-Christian, "Alapetite Gabriel Ferdinand", Famille Parent-Cadart-Ponsar (in French), retrieved 2017-09-25

- "Philippe Thomas", Le Site Sfaxien (in French), retrieved 2017-09-01

- Résumé des Services M Apetite (Gabriel, Ferdinand) (in French), Préfecture du Pas-de-Calais, retrieved 2017-09-25 – via Leonore

- Rodd Balek (1920–1921), La Tunisie après la guerre (in French), Paris: éd. Publication du Comité de l’Afrique française

- Schmidt, M.E. (2012-12-06), Alexandre Ribot: Odyssey of a Liberal in the Third Republic, Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 978-94-010-2067-1, retrieved 2017-09-26

- Storm, Eric; Al Tuma, Ali (2015-12-22), Colonial Soldiers in Europe, 1914-1945: "Aliens in Uniform" in Wartime Societies, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-33098-1, retrieved 2017-09-26

Further reading

[edit]- Gabriel Alapetite, 1854-1932: ambassadeur de France, P. Hartmann, 1934

- Leblond, François (2017-03-29), Gabriel Alapetite, un grand serviteur de l'Etat: Un préfet modèle pour nos générations, Librinova, ISBN 979-10-262-0966-9