A garbhagriha (Sanskrit: गर्भगृह, romanized: Garbhagṛha) is the innermost sanctuary of Hindu and Jain temples, what may be called the "holy of holies" or "sanctum sanctorum".

The term garbhagriha (literally, "womb chamber") comes from the Sanskrit words garbha for womb and griha for house. Although the term is often associated with Hindu temples, it is also found in Jain and Buddhist temples.[1]

The garbhagriha is the location of the murti (sacred image) of the temple's primary deity. This might be a murti of Shiva, as the lingam, his consort the Goddess in her consecrated image or yoni symbol, Vishnu or his spouse, or some other god in symbol or image.[2] In the Rajarani temple in Bhubaneswar, near Puri, there is no symbol in that lightless garbhagriha.[3]

Architecture

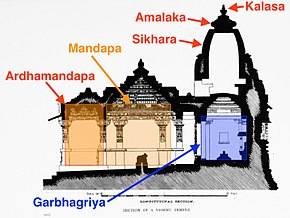

A garbhagriha is normally square (though there are exceptions[4]), sits on a plinth, and is also at least approximately a cube. Compared to the size of the temple that may surround it, and especially the large tower commonly found above it, a garbhagriha is a rather small room.

The typical Hindu and Jain garbhagriha is preceded by one or more adjoining pillared mandapas (porches or halls), which are connected to the sanctum by an open or closed vestibule (antarala),[5] and through which the priests or devotees may approach the holy shrine in order to worship the presence of the deity in profound, indrawn meditation.[6]

In addition to being square, the garbhagriha is most often windowless, has only one entrance that faces the eastern direction of the rising sun (though there are exceptions[7]), and is sparsely lit to allow the devotee's mind to focus on the tangible form of the divine within it. The garbhagriha is also commonly capped by a great tower superstructure. The two main styles of towers are the shikhara (in India's northern region) or the vimana (in India's southern region).

An early prototype for this style of garbhagriha is the sixth century CE Deogarh temple in Uttar Pradesh State’s Jhansi district (which also has a small stunted shikhara over it).[8] The style fully emerged in the eighth century CE and developed distinct regional variations in Orissa, central India, Rajasthan, and Gujarat.[9] However, it should be remembered that throughout South Asia stone structures were always vastly outnumbered by buildings made of perishable materials, such as wood, bamboo, thatch and brick.[10] Thus, while some early stone examples have survived, the earliest use of a square garbhagriha cannot be categorically dated simply because its original structural materials have long since decomposed.

Some exceptions to the square-rule exist. In some temples, particularly at an early date, the garbhagriha is not quite square, and in some later ones it may be rectangular to ensure enough symmetrical space for the housing of more than one deity, such as at the Savadi Trimurti Temple.[11] Other rectangular garbhagriha include those at Sasta Temple (Karikkad Ksetram), Manjeri, and at Varahi Deula.

There are a very few examples of larger variance: the chamber at Gudimallam is both semi-circular at the rear, and set below the main floor level of the temple (see bottom inset image).

The famous 7th-century Durga temple, Aihole also has a rounded apse at the garbagriha end, which is echoed in the shape of the chamber. So, too, does the garbhagriha at Triprangode Siva Temple have a rounded apse. Fully round garbhagriha exist at the Siva Temple, Masaon, as well as at Siva Temple, Chandrehe.[12]

Orientation

The tower that caps the garbhagriha forms the main vertical axis of the temple,[13] and is usually understood to represent the axis of the world through Mount Meru. By contrast, the garbhagriha usually forms part of the main horizontal axis of the temple, which generally runs east-west. In those temples where there is also a cross-axis, the garbhagṛiha is generally at their intersection.

The location for the garbhagriha is ritually oriented at the point of total equilibrium and harmony as a representative of a microcosm of the Universe. This is achieved through a cosmic diagram (the vastu purusha mandala in Hindu temple architecture), which is used to ritually trace a hierarchy of deities on the ground where a new temple is to be built.[14] Indeed, the ground plans of many Indian temples are themselves in the form of a rectilinear abstract mandala pattern.[15] The murti of the deity is ritually and symmetrically positioned at the center of the garbhagriha shrine, and represents the "axis mundi", the axis about which the world is oriented, and which connects heaven and earth.[16][17]

This symmetry highlights the principal axes underlying the temple. Two cardinal axes, crossing at right angles, orient the ground plan: a longitudinal axis (running through the doorway, normally east-west) and a transverse one (normally north-south). Diagonal axes run through the garbhagriha corners and, since a square is the usual basis of the whole vimana plan, through the exterior corners.[18]

There are some exceptions to the east-facing rule. For example, the garbhagriha at the Sasta Temple (Karikkad Ksetram) in Manjeri, the Siva Temple in Masaon, and the Siva Temple in Chandrehe, all face west. Ernest Short suggests that these western-facing Shiva temples are the result of rules in the Shulba Sutras which set out the appropriate forms and symbolism of a Hindu temple. Whereas a shrine of Brahman was open on all four sides, Short says, a temple of Vishnu faced east, while that of Shiva, west.[19]

Hinduism

The purpose of every Hindu temple is to be a house for a deity whose image or symbol is installed and whose presence is concentrated at the heart and focus of the building.[20]

Entrance to the Hindu garbhagriha has been traditionally restricted to priests who perform the services there,[21] though in temples that are used in active worship (as opposed to historic monuments), access is at least restricted to Hindus. In Jain temples, all suitably bathed and purified Jains are allowed to enter inside.[22]

As a house for the deity, the function of the shrine is not just to offer shelter but also to manifest the presence within, to be a concrete realisation, and a coming into the world of the deity. Symbolically the shrine is the body of the god, as well as the house, and many Sanskrit terms for architectural elements reflect this.[23] The embodied divinity, its power radiating from within, is revealed in the exterior, where architectural expression chiefly resides.[24] This is consistent with other early Hindu images that often represented cosmic parturition—-the coming into present existence of a divine reality that otherwise remains without form-—as well as “meditational constructs".[25]

Other languages

In Tamil, the garbhagriha is called karuvarai meaning the interior of the sanctum sanctorum and means "womb chamber". The word "karu" means foetus and "arai" means a room.

Satcitananda is an epithet and description for the subjective experience of the ultimate unchanging reality, such as that typified by the garbhagriha. Devotees of the Sabarimala Temple may refer to the garbhagriha as sannidhanam.[26]

Sreekovil is another term for garbhagriha.[27]

Notes

- ^ Sir Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture, Edited by Dan Cruickshank (20th ed.). 1996. According to this edition of Sir Banister Fletcher's History of Architecture, the Jains consider themselves Hindus in a broad sense, and therefore the temple architecture of Jains in a given period and region is not fundamentally different from Hindu temple architecture, often being the work of the same architects and craftsmen, and even patronised by the same rulers.

- ^ Campbell, Joseph. Creative Mythology. p. 168.

- ^ Zimmer, Heinrich; Campbell, Joseph (1955). The Art of Indian Asia, Bollingen Series XXXIX. New York: Pantheon Books. p. Vol. II, Plates 336–43.

- ^ Bunce, Frederick W. (2007). Monuments of India and the Indianized States: The Plans of Major and Notable Temples, Tombs, Palaces and Pavilions, South-East Asia.

- ^ Wu, Nelson I. (1963). Chinese and Indian Architecture: The City of Man, the Mountain of God, and the Realm of the Immortals. Studio Vista. ISBN 9780289370711.

- ^ Campbell, Joseph. Creative Mythology. p. 168.

- ^ Bunce, Frederick W. (2007). Monuments of India and the Indianized States: The Plans of Major and Notable Temples, Tombs, Palaces and Pavilions, South-East Asia.

- ^ Short, Ernest (1936). Ernest ShoA History of Religious Architecture.

- ^ Short, Ernest (1936). Ernest ShoA History of Religious Architecture.

- ^ Sir Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture, Edited by Dan Cruickshank (20th ed.). 1996.

- ^ Hardy, p. 31, note 5,

- ^ Bunce, Frederick W. (2007). Monuments of India and the Indianized States: The Plans of Major and Notable Temples, Tombs, Palaces and Pavilions, South-East Asia.

- ^ Hardy, 16-17

- ^ Hardy, p. 17

- ^ Mann, A.T. (1993). Sacred Architecture. Element. ISBN 9781852303914.

- ^ Short, Ernest (1936). Ernest ShoA History of Religious Architecture.

- ^ Thapar, Binda (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions. p. 43. ISBN 0-7946-0011-5.

- ^ Hardy, 17

- ^ Short, Ernest (1936). Ernest ShoA History of Religious Architecture.

- ^ Hardy, 16

- ^ Hardy, 16

- ^ Hardy, 30, note 1

- ^ Sir Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture, Edited by Dan Cruickshank (20th ed.). 1996.

- ^ Sir Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture, Edited by Dan Cruickshank (20th ed.). 1996.

- ^ Meister, Michael (1987). "Hindu Temples" in the Gale Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol 13.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Sannidhanam". Archived from the original on 2012-03-13.

- ^ "Sreekovil." Definitions.net. STANDS4 LLC, 2023. Web. 22 Apr. 2023. <https://www.definitions.net/definition/Sreekovil>.

References

- Hardy, Adam, Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation : the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries, 1995, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 8170173124, 9788170173120, google books.

- George Michell, Monuments of India (Penguin Guides, Vol. 1, 1989).