| Hemoglobin E disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Haemoglobin E |

| |

| Crystal structure of Hemoglobin E mutant (Glu26Lys) PDB entry 1vyt. Alpha chain in pink, beta chain in red. The lysine mutation highlighted as white spheres. | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

Hemoglobin E (HbE) is an abnormal hemoglobin with a single point mutation in the β chain. At position 26 there is a change in the amino acid, from glutamic acid to lysine (E26K). Hemoglobin E is very common among people of Southeast Asian, Northeast Indian, Sri Lankan and Bangladeshi descent.[1][2]

The βE mutation affects β-gene expression creating an alternate splicing site in the mRNA at codons 25-27 of the β-globin gene. Through this mechanism, there is a mild deficiency in normal β mRNA and production of small amounts of anomalous β mRNA. The reduced synthesis of β chain may cause β-thalassemia. Also, this hemoglobin variant has a weak union between α- and β-globin, causing instability when there is a high amount of oxidant.[3] HbE can be detected on electrophoresis.

Hemoglobin E disease (EE)

Hemoglobin E disease results when the offspring inherits the gene for HbE from both parents. At birth, babies homozygous for the hemoglobin E allele do not present symptoms because they still have HbF (fetal hemoglobin). In the first months of life, fetal hemoglobin disappears and the amount of hemoglobin E increases, so the subjects start to have a mild β-thalassemia. Subjects homozygous for the hemoglobin E allele (two abnormal alleles) have a mild hemolytic anemia and mild enlargement of the spleen.

Hemoglobin E trait: heterozygotes for HbE (AE)

Heterozygous AE occurs when the gene for hemoglobin E is inherited from one parent and the gene for hemoglobin A from the other. This is called hemoglobin E trait, and it is not a disease. People who have hemoglobin E trait (heterozygous) are asymptomatic and their state does not usually result in health problems. They may have a low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and very abnormal red blood cells (target cells), but clinical relevance is mainly due to the potential for transmitting E or β-thalassemia.[4]

Sickle-Hemoglobin E Disease (SE)

Compound heterozygotes with sickle-hemoglobin E disease result when the gene of hemoglobin E is inherited from one parent and the gene for hemoglobin S from the other. As the amount of fetal hemoglobin decreases and hemoglobin S increases, a mild hemolytic anemia appears in the early stage of development. Patients with this disease experience some of the symptoms of sickle cell anemia, including mild-moderate anemia, increased risk of infection, and painful sickling crises.[5]

Hemoglobin E/β-thalassaemia

People who have hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia have inherited one gene for hemoglobin E from one parent and one gene for β-thalassemia from the other parent. Hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia is a severe disease, and it still has no universal cure. However, the mutation is amenable to genome editing at high efficiency in preclinical studies.[6] It affects more than a million people in the world.[7] Symptoms of hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia vary but can include growth retardation, enlargement of the spleen (splenomegaly) and liver (hepatomegaly), jaundice, bone abnormalities, and cardiovascular problems.[8] Recommended course of treatment depends on the nature and severity of the symptoms and may involve close monitoring of hemoglobin levels, folic acid supplements, and potentially regular blood transfusions.[8]

There is a variety of phenotypes depending on the interaction of HbE and α-thalassemia. The presence of the α-thalassemia reduces the amount of HbE usually found in HbE heterozygotes. In other cases, in combination with certain thalassemia mutations, it provides an increased resistance to malaria (P. falciparum).[4] This disease was first described by Virginia Minnich in 1954, who discovered a high prevalence of it in Thailand and initially referred to it as "Mediterranean Anaemia."[8]

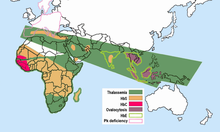

Epidemiology

Hemoglobin E is most prevalent in mainland Southeast Asia (Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam[9]), Sri Lanka, Northeast India and Bangladesh. In mainland Southeast Asia, its prevalence can reach 30 or 40%, and Northeast India, in certain areas it has carrier rates that reach 60% of the population. In Thailand the mutation can reach 50 or 70%, and it is higher in the northeast of the country. In Sri Lanka, it can reach up to 40% and affects those of Sinhalese and Vedda descent.[10][11] It is also found at high frequencies in Bangladesh and Indonesia.[12][13] The trait can also appear in people of Turkish, Chinese and Filipino descent.[1] The mutation is estimated to have arisen within the last 5,000 years.[14] In Europe, there have been found cases of families with hemoglobin E, but in these cases, the mutation differs from the one found in South-East Asia. This means that there may be different origins of the βE mutation.[15][16]

References

- ^ a b "Hemoglobin e Trait - Health Encyclopedia - University of Rochester Medical Center". Archived from the original on 2017-08-30. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-24. Retrieved 2017-06-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Chernoff AI, Minnich V, Nanakorn S, et al. (1956). "Studies on hemoglobin E. I. The clinical, hematologic, and genetic characteristics of the hemoglobin E syndromes". J Lab Clin Med. 47 (3): 455–489. PMID 13353880.

- ^ a b Bachir, D; Galacteros, F (November 2004), Hemoglobin E disease. (PDF), Orphanet Encyclopedia, archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016, retrieved January 13, 2014

- ^ Arkansas Department of Health. "Sickle-Hemoglobin E Disease Fact Sheet" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-02-28. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ Badat, M; Ejaz, A; Hua, P; Rice, S; Zhang, W; Hentges, LD; Fisher, CA; Denny, N; Schwessinger, R; Yasara, N; Roy, NBA; Issa, F; Roy, A; Telfer, P; Hughes, J; Mettananda, S; Higgs, DR; Davies, JOJ (19 April 2023). "Direct correction of haemoglobin E β-thalassaemia using base editors". Nature Communications. 14 (1): 2238. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.2238B. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-37604-8. PMC 10115876. PMID 37076455.

- ^ Vichinsky E (2007). "Hemoglobin E Syndromes". Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2007: 79–83. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.79. PMID 18024613. S2CID 10435042.

- ^ a b c Fucharoen, Suthat; Weatherall, David J. (2012-08-01). "The Hemoglobin E Thalassemias". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2 (8): a011734. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a011734. ISSN 2157-1422. PMC 3405827. PMID 22908199.

- ^ Hemoglobin E Trait, University of Rochester Medical Center, retrieved January 13, 2014

- ^ Sarkar, Jayanta; Ghosh, G. C. (2003). Populations of the SAARC Countries: Bio-cultural Perspectives. Sterling Publishers Pvt. ISBN 9788120725621.

- ^ Roychoudhury, Arun K.; Nei, Masatoshi (1985). "Genetic Relationships between Indians and Their Neighboring Populations". Human Heredity. 35 (4). S. Karger AG: 201–206. doi:10.1159/000153545. ISSN 1423-0062.

- ^ Kumar, Dhavendra (2012-09-15). Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent. Springer. ISBN 9781402022319.

- ^ Olivieri NF, Pakbaz Z, Vichinsky E (2011). "Hb E/beta-thalassaemia: a common & clinically diverse disorder". Indian J. Med. Res. 134 (4): 522–31. PMC 3237252. PMID 22089616.

- ^ Ohashi; et al. (2004). "Extended linkage disequilibrium surrounding the hemoglobin E variant due to malarial selection". Am J Hum Genet. 74 (6): 1189–1208. doi:10.1086/421330. PMC 1182083. PMID 15114532. Free full text Archived 2023-01-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kazazian HH, JR., Waber PG, Boehm CD, Lee JI, Antonarakis SE, Fairbanks VF. (1984). "Hemoglobin E in Europeans: Further Evidence for Multiple Origins of the βE-Globin Gene". Am J Hum Genet. 36 (1): 212–217. PMC 1684388. PMID 6198908.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Free full text Archived 2023-01-25 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Bain, Barbara J (June 2006). Blood cells: a practical guide (4th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-4265-6.