The keyboard concertos, BWV 1052–1065, are concertos for harpsichord (or organ), strings and continuo by Johann Sebastian Bach. There are seven complete concertos for a single harpsichord (BWV 1052–1058), three concertos for two harpsichords (BWV 1060–1062), two concertos for three harpsichords (BWV 1063 and 1064), and one concerto for four harpsichords (BWV 1065). Two other concertos include solo harpsichord parts: the concerto BWV 1044, which has solo parts for harpsichord, violin and flute, and Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, with the same scoring. In addition, there is a nine-bar concerto fragment for harpsichord (BWV 1059) which adds an oboe to the strings and continuo.

Most of Bach's harpsichord concertos (with the exception of the 5th Brandenburg Concerto) are thought to be arrangements made from earlier concertos for melodic instruments probably written in Köthen. In many cases, only the harpsichord version has survived. They are among the first concertos for keyboard instrument ever written.

History

The music performed by the Society was of various kinds; hence we may assume that violin and clavier concertos by Bach were also performed, though more frequently, perhaps, at Bach's house ... The most flourishing time in Bach's domestic band was, no doubt, from about 1730 until 1733, since the grown-up sons, Friedemann and Emanuel, were still living in their father's house, Bernhard was already grown up, and Krebs, who had been Sebastian's pupil since 1726, was beginning to display his great talents ... Whether Bach ever wrote violin concertos expressly for them must remain undecided ... In this branch of art he devoted himself chiefly at Leipzig to the clavier concerto.

— Philipp Spitta, "Johann Sebastian Bach," 1880[1]

The concertos for one harpsichord, BWV 1052–1059, survive in an autograph score, now held in the Berlin State Library. Based on the paper's watermarks and the handwriting, it has been attributed to 1738 or 1739.[2] As Peter Williams records, these concertos are almost all considered to be arrangements by Bach of previously existing works. Establishing the history or purpose of any of the harpsichord concertos, however, is not a straightforward task. At present, attempts to reconstruct the compositional history can only be at the level of plausible suggestions or conjectures, mainly because very little of Bach's instrumental music has survived and, even when it has, sources are patchy. In particular this makes it hard not only to determine the place, time and purpose of the original compositions but even to determine the original key and intended instrument.[3]

The harpsichord part in the autograph manuscript is not a "fair copy" but a composing score with numerous corrections. The orchestral parts on the other hand were executed as a fair copy.[2][4] Various possible explanations have been proposed as to why Bach assembled the collection of harpsichord concertos at this particular time. One centres on his role as director of the Collegium Musicum in Leipzig, a municipal musical society, which gave weekly concerts at the Café Zimmermann, drawing many performers from students at the university. Bach served as director from spring 1729 to summer 1737; and again from October 1739 until 1740 or 1741. John Butt suggests that the manuscript was prepared for performances on Bach's resumption as director in 1739, additional evidence coming from the fact that the manuscript subsequently remained in Leipzig.[5] Peter Wollny, however, considers it unlikely that The Collegium Musicum would have required orchestral parts that were so neatly draughted; he considers it more plausible that the manuscript was prepared for a visit that Bach made to Dresden in 1738 when he would almost certainly have given private concerts in court (or to the nobility) and the ripieno parts would have been played by the resident orchestra.[2][6] Peter Williams has also suggested that the collection would have been a useful addition to the repertoire of his two elder sons, Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, both employed as professional keyboard-players at the time of writing. Williams has also speculated that it might not be mere coincidence that the timing matched the publication of the first ever collection of keyboard concertos, the widely acclaimed and well-selling Organ concertos, Op. 4 of George Frideric Handel published in London and Paris in 1738.[7]

The concertos for two or more harpsichords date from a slightly earlier period. The parts from the concerto for four harpsichords BWV 1065 (Bach's arrangement of the Concerto for Four Violins, RV 580, by Antonio Vivaldi), have been dated to around 1730.[5] Whereas the harpsichord concertos were composed partly to showcase Bach's own prowess at the keyboard, the others were written for different purposes, one of them being as Hausmusik—music for domestic performance within the Bach household at the Thomasschule in Leipzig. Johann Nikolaus Forkel, Bach's first biographer, recorded in 1802 that the concertos for two or more harpsichords were played with his two elder sons. Both of them corresponded with Forkel and both remained in the parental home until the early 1730s: Wilhelm Friedemann departed in 1733 to take up an appointment as organist at the Sophienkirche in Dresden; and in 1735 Carl Philipp Emanuel moved to the university in Frankfurt an der Oder to continue training for his (short-lived) legal career. There are also first-hand accounts of music-making by the entire Bach family, although these probably date from the 1740s during visits to Leipzig by the two elder sons: one of Bach's pupils, J. F. K. Sonnenkalb, recorded that house-concerts were frequent and involved Bach together with his two elder sons, two of his younger sons—Johann Christoph Friedrich and Johann Christian—as well as his son-in-law Johann Christoph Altnickol. It is also known that Wilhelm Friedemann visited his father for one month in 1739 with two distinguished lutenists (one of them was Sylvius Weiss), which would have provided further opportunities for domestic music-making. The arrangement of the organ sonatas, BWV 525–530, for two harpsichords with each player providing the pedal part in the left hand, is also presumed to have originated as Hausmusik, a duet for the elder sons.[8]

The harpsichord concertos were composed in a manner completely idiomatic to the keyboard (this was equally true for those written for two or more harpsichords). They were almost certainly originally conceived for a small chamber group, with one instrument per desk, even if performed on one of the newly developed fortepianos, which only gradually acquired the potential for producing a louder dynamic. The keyboard writing also conforms to a practice that lasted until the early nineteenth century, namely the soloist played along with the orchestra in tutti sections, only coming into prominence in solo passages.[9]

The question "Did J.S. Bach write organ concertos?" has led Christoph Wolff[10] and Gregory Butler [11] to propose that Bach originally wrote the concertos BWV 1052 and BWV 1053 for solo organ and orchestra. Among other evidence, they note that both concertos consist of movements that Bach had previously used as instrumental sinfonias in 1726 cantatas with obbligato organ providing the melody instrument (BWV 146, BWV 169 and BWV 188). A Hamburg newspaper reported on a recital by Bach in 1725 on the Silbermann organ in the Sophienkirche, Dresden, mentioning in particular that he had played concertos interspersed with sweet instrumental music ("diversen Concerten mit unterlauffender Doucen Instrumental-Music"). Wolff (2016), Rampe (2014), Gregory Butler and Matthew Dirst have suggested that this report might refer to versions of the cantata movements or similar works. Williams (2016) describes the newspaper article as "tantalising" but considers it possible that in the hour-long recital Bach played pieces from his standard organ repertoire (preludes, chorale preludes) and that the reporter was using musical terms in a "garbled" way. In another direction Williams has listed reasons why, unlike Handel, Bach may not have composed concertos for organ and a larger orchestra: firstly, although occasionally used in his cantatas, the Italian concerto style of Vivaldi was quite distant from that of Lutheran church music; secondly, the tuning of the baroque pipe organ would jar with that of a full orchestra, particularly when playing chords; and lastly, the size of the organ loft limited that of the orchestra.[12] Wolff, however, notes that Bach's congregation did not object to his use of the organ obliggato in the sinfonia movements in the aforementioned cantatas.[10]

The earliest extant sources regarding Bach's involvement with the keyboard concerto genre are his Weimar concerto transcriptions, BWV 592–596 and 972–987 (c. 1713–1714), and his fifth Brandenburg Concerto, BWV 1050, the early version of which, BWV 1050a, may have originated before Bach left Weimar in 1717.[13][14]

Concertos for single harpsichord

The works BWV 1052–1057 were intended as a set of six, shown in the manuscript in Bach's traditional manner beginning with 'J.J.' (Jesu juva, "Jesus, help") and ending with 'Finis. S. D. Gl.' (Soli Deo Gloria). Aside from the Brandenburg concertos, it is the only such collection of concertos in Bach's oeuvre, and it is the only set of concertos from his Leipzig years. The concerto BWV 1058 and fragment BWV 1059 are at the end of the score, but they are an earlier attempt at a set of works (as shown by an additional J.J.), which was, however, abandoned.[15]

Concerto No. 1 in D minor, BWV 1052

Scoring: harpsichord solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

The earliest surviving manuscript of the concerto can be dated to 1734; it was made by Bach's son Carl Philipp Emanuel and contained only the orchestral parts, the cembalo part being added later by an unknown copyist. This version is known as BWV 1052a. The definitive version BWV 1052 was recorded by Bach himself in the autograph manuscript of all eight harpsichord concertos BWV 1052–1058, made around 1738.[16]

In the second half of the 1720s, Bach had already written versions of all three movements of the concerto for two of his cantatas with obbligato organ as solo instrument: the first two movements for the sinfonia and first choral movement of Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal in das Reich Gottes eingehen, BWV 146 (1726); and the last movement for the opening sinfonia of Ich habe meine Zuversicht, BWV 188 (1728). In these cantata versions the orchestra was expanded by the addition of oboes.[17]

Like the other harpsichord concertos, BWV 1052 has been widely believed to be a transcription of a lost concerto for another instrument. Beginning with Wilhelm Rust and Philipp Spitta, many scholars suggested that the original melody instrument was the violin, because of the many violinistic figurations in the solo part—string-crossing, open string techniques—all highly virtuosic. Williams (2016) has speculated that the copies of the orchestral parts made in 1734 (BWV 1052a) might have been used for a performance of the concerto with Carl Philipp Emanuel as soloist. There have been several reconstructions of the putative violin concerto; Ferdinand David made one in 1873; Robert Reitz in 1917; and Wilfried Fischer prepared one for Volume VII/7 of the Neue Bach Ausgabe in 1970 based on BWV 1052. In 1976, in order to resolve playability problems in Fischer's reconstruction, Werner Breig suggested amendments based on the obbligato organ part in the cantatas and BWV 1052a.[18][19][20]

In the twenty-first century, however, Bach scholarship has moved away from any consensus regarding a violin original. In 2016, for example, two leading Bach scholars, Christoph Wolff and Gregory Butler, both published independently conducted research that led each to conclude that the original form of BWV 1052 was an organ concerto composed within the first few years of Bach's tenure in Leipzig. (Previous scholarship often held that Bach composed the original in Weimar or Cöthen.) Both relate the work to performances by Bach of concerted movements for organ and orchestra in Dresden and Leipzig. Wolff also details why the violinistic figuration in the harpsichord part does not demonstrate that it is a transcription from a previous violin part; for one thing, the "extended and extreme passagework" in the solo part "cannot be found in any of Bach's violin concertos"; for another, he points to other relevant Bach keyboard works that "display direct translations of characteristic violin figuration into idiomatic passagework for the keyboard." Also Peter Wollny disagrees with the hypothesis that the works was originally a violin concerto.[21][22][23]

As Werner Breig has shown, the first harpsichord concerto Bach entered into the autograph manuscript was BWV 1058, a straightforward adaptation of the A minor violin concerto. He abandoned the next entry BWV 1059 after only a few bars to begin setting down BWV 1052 with a far more comprehensive approach to recomposing the original than merely adapting the part of the melody instrument.[24][25]

The concerto has similarities with Vivaldi's highly virtuosic Grosso Mogul violin concerto, RV 208, which Bach had previously transcribed for solo organ in BWV 594. It is one of Bach's greatest concertos: in the words of Jones (2013) it "conveys a sense of huge elemental power." This mood is created in the opening sections of the two outer movements. Both start in the manner of Vivaldi with unison writing in the ritornello sections—the last movement begins as follows:[24][25]

Bach then proceeds to juxtapose passages in the key of D minor with passages in A minor: in the first movement this concerns the first 27 bars; and in the last the first 41 bars. These somewhat abrupt changes in tonality convey the spirit of a more ancient modal type of music. In both movements the A sections are fairly closely tied to the ritornello material which is interspersed with brief episodes for the harpsichord. The central B sections of both movements are freely developed and highly virtuosic; they are filled with violinistic figurations including keyboard reworkings of bariolage, a technique that relies on the use of the violin's open strings. The B section in the first movement starts with repeated note bariolage figures:[24][25]

which, when they recur later, become increasingly virtuosic and eventually merge into brilliant filigree semidemiquaver figures—typical of the harpsichord—in the final extended cadenza-like episode before the concluding ritornello.[24][25]

Throughout the first movement the harpsichord part also has several episodes with "perfidia"—the same half bar semiquaver patterns repeated over a prolonged period. Both outer movements are in an A–B–A′ form: the A section of the first movement is in bars 1–62, the B section starts with the bariolage passage and lasts from bar 62 to bar 171, the A′ section lasts from bar 172 until the end; the A section of the final movement is in bars 1–84, the B section in bars 84–224, and the A′ section from bar 224 until the end. In the first movement the central section is in the keys of D minor and E minor; in the last movement the keys are D minor and A minor. As in the opening sections, the shifts between the two minor tonalities are sudden and pronounced. In the first movement Bach creates another equally dramatic effect by interrupting the relentless minor-key passages with statements of the ritornello theme in major keys. Jones describes these moments of relief as providing "a sudden, unexpected shaft of light."[24][25]

The highly rhythmic thematic material of the solo harpsichord part in the third movement has similarities with the opening of the third Brandenburg Concerto.[24][25]

In both B sections Bach adds unexpected features: in the first movement what should be the last ritornello is interrupted by a brief perfidia episode building up to the true concluding ritornello; similarly in the last movement, after five bars of orchestral ritornello marking the beginning of the A′ section, the thematic material of the harpsichord introduces a freely developed 37-bar highly virtuosic episode culminating in a fermata (for an extemporised cadenza) before the concluding 12 bar ritornello.[24][25]

The slow movement, an Adagio in G minor and 3

4 time, is built on a ground bass which is played in unison by the whole orchestra and the harpsichord in the opening ritornello.[24][25]

It continues throughout the piece providing the foundations over which the solo harpsichord spins a florid and ornamented melodic line in four long episodes.[24][25]

The subdominant tonality of G minor also plays a role in the outer movements, in the bridging passages between the B and A′ sections. More generally Jones (2013) has pointed out that the predominant keys in the outer movements centre around the open strings of the violin.[24][25]

Several hand copies of the concerto—the standard method of transmission—survive from the 18th century; for instance there are hand copies by Johann Friedrich Agricola around 1740, by Christoph Nichelmann and an unknown scribe in the early 1750s. Its first publication in print was in 1838 by the Kistner Publishing House.[26]

The performance history in the nineteenth century can be traced back to the circle of Felix Mendelssohn. In the first decade of the 19th century the harpsichord virtuoso and great aunt of Mendelssohn, Sara Levy, gave public performances of the concerto in Berlin at the Sing-Akademie, established in 1791 by the harpsichordist Carl Friedrich Christian Fasch and subsequently run by Mendelssohn's teacher Carl Friedrich Zelter.[27] In 1824 Mendelssohn's sister Fanny performed the concerto at the same venue.[28] In 1835 Mendelssohn played the concerto in his first year as director of the Gewandhaus in Leipzig.[27] There were further performances at the Gewandhaus in 1837, 1843 and 1863.[29] Ignaz Moscheles, a friend and teacher of Mendelssohn as well as a fellow devotee of Bach, gave the first performance of the concerto in London in 1836 at a benefit concert, adding one flute and two clarinets, bassoons and horns to the orchestra.[30] In a letter to Mendelssohn, he disclosed that he intended the woodwind section to have the "same position in the Concerto as the organ in the performance of a Mass."[30] Robert Schumann subsequently described Moscheles' reorchestration as "very beautiful."[30] The following year Moscheles performed the concerto at the Academy of Ancient Music with Bach's original string orchestration.[30] The Musical World reported that Moscheles "elicited such unequivocal testimonies of delight, as the quiet circle of the Ancient Concert subscribers rarely indulge in."[30] In 1838 the concerto was published in Leipzig.[31][32] Johannes Brahms later composed a cadenza for the last movement of the concerto, which was published posthumously.[33]

Concerto No. 2 in E major, BWV 1053

| ||

| 1. Allegro | 2. Siciliano | 3. Allegro |

Scoring: harpsichord solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

Several prominent scholars, Siegbert Rampe and Dominik Sackmann, Ulrich Siegele, and Wilfried Fischer have argued that Bach transcribed this concerto from a lost original for oboe or oboe d'amore (Rampe and Sackmann argued for a dating in 1718-19).[34][35][36] Alternatively, Christoph Wolff has suggested that it might have been a 1725 concerto for organ.[37] An organ version exists, like BWV 1052, in a later transcription in his cantatas Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169 and Ich geh und suche mit Verlangen, BWV 49.[21]

Bach changed his method of arrangement with this work, significantly altering the ripieno parts from the original concerto for the first time, limited much more to the tutti sections. The lower string parts were much reduced in scope, allowing the harpsichord bass to be more prominent, and the upper strings were likewise modified to allow the harpsichord to be at the forefront of the texture.

Concerto No. 3 in D major, BWV 1054

| ||

| 1. Allegro | 2. Adagio e piano sempre | 3. Allegro |

Scoring: harpsichord solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

Length: c. 17 minutes

The surviving violin concerto in E major, BWV 1042 was the model for this work, which was transposed down a tone to allow the top note E6 to be reached as D6, the common top limit on harpsichords of the time. The opening movement is one of the rare Bach concerto first movements in da capo A–B–A form.

In 1845 Ignaz Moscheles performed the concerto in London.[38]

Concerto No. 4 in A major, BWV 1055

| ||

| 1. Allegro | 2. Larghetto | 3. Allegro ma non tanto |

Scoring: harpsichord solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

Length: c. 14 minutes

While scholars agree that the concerto BWV 1055 is based on a lost original, different theories have been proposed for the instrument Bach used in that original. That it was an oboe d'amore was proposed in 1936 by Donald Tovey,[39] in 1957 by Ulrich Siegele,[35] in 1975 by Wilfried Fischer,[40] and in 2008 by Pieter Dirksen.[36] Alternatively, Wilhelm Mohr argued in 1972 that the original was a concerto for viola d'amore.[41] Most recently, however, in 2015 musicologist Peter Wollny (the director of the Bach Archive in Leipzig) argued that the "entire first movement" may instead "originate as a composition for unaccompanied keyboard instrument," since the movement "is conceived on the basis of the harpsichord as solo instrument, to such an extent that the strings are not even permitted to deploy a ritornello theme of their own, but from the first bar onwards assume their role as accompanists and thus step into the background to enable the solo part to develop unhindered; in the case of a melody instrument like the oboe such a design would be unthinkable."[2]

Wollny notes that whatever the origins, the final work is the only Bach Harpsichord Concerto for which "a complete original set of parts has survived"; included is a "fully figured continuo part," which scholars agree was for a second harpsichord.[2] Wollny sees the second movement as a siciliana and the finale as having the "gait of a rapid minuet."

Concerto No. 5 in F minor, BWV 1056

| ||

| 1. Allegro moderato | 2. Largo | 3. Presto |

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Concerto for Harpsichord No. 1 in F minor, BWV 1056 Concerto for Harpsichord No. 2 in F major, BWV 1057 Concerto for Harpsichord in G minor, BWV 1058 Concerto for Harpsichord in D minor, BWV 1059 performed by Gustav Leonhardt and the Leonhardt Consort in 1968 Here on archive.org |

Scoring: harpsichord solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

Length: c. 10 minutes

The outer movements probably come from a violin concerto which was in G minor.

The middle movement is probably from an oboe concerto in F major; is also the sinfonia to the cantata Ich steh mit einem Fuß im Grabe, BWV 156; and closely resembles the opening Andante of a Flute Concerto in G major (TWV 51:G2) by Georg Philipp Telemann in that the soloists play essentially identical notes for the first two-and-a-half measures. Although the chronology cannot be known for certain, Steven Zohn has presented evidence that the Telemann concerto came first, and that Bach intended his movement as an elaboration of his friend Telemann's original.[42] The middle movement was used in the soundtrack for Woody Allen's 1986 film Hannah and Her Sisters.[43]

Concerto No. 6 in F major, BWV 1057

| ||

| 1. Allegro | 2. Andante | 3. Allegro assai |

Scoring: harpsichord solo, flauto dolce (recorder) I/II, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

Length: c. 17 minutes

An arrangement of Brandenburg Concerto No. 4, BWV 1049, which has a concertino of violin and two recorders. Besides transposing, recorder parts have few modifications, except in the second movement in which most of their melodic function is transferred to the soloist. Bach wrote the harpsichord part as a combination of the violin material from the original concerto and a written out continuo.[44]

Concerto No. 7 in G minor, BWV 1058

| ||

| 1. Allegro | 2. Andante | 3. Allegro assai |

Scoring: harpsichord solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

Length: c. 14 minutes

Probably Bach's first attempt at writing out a full harpsichord concerto, this is a transcription of the violin concerto in A minor, BWV 1041, one whole tone lower to fit the harpsichord's range. It seems Bach was dissatisfied with this work, the most likely reason being that he did not alter the ripieno parts very much, so the harpsichord was swamped by the orchestra too much to be an effective solo instrument.[15]

Bach did not continue the intended set, which he had marked with 'J.J.' (for Jesu juva, "Jesus, help") at the start of this work, as was his custom for a set of works. He wrote only the short fragment BWV 1059.[15]

In 1845 Ignaz Moscheles performed the concerto in London.[38]

Concerto in D minor, BWV 1059 (fragment)

Scored for harpsichord, oboe and strings in the autograph manuscript, Bach abandoned this concerto after entering only nine bars. As with the other harpsichord concertos that have corresponding cantata movements (BWV 1052, 1053 and 1056), this fragment corresponds to the opening sinfonia of the cantata Geist und Seele wird verwirret, BWV 35, for alto, obbligato organ, oboes, taille and strings. Rampe (2013) summarises the musicological literature discussing the possibility of a lost instrumental concerto on which the fragment and movements of the cantata might have been based. A reconstruction of an oboe concerto was made in 1983 by Arnold Mehl with the two sinfonias from BWV 35 as outer movements and the opening sinfonia of BWV 156 as slow movement.[45]

Concertos for two harpsichords

Concerto in C minor, BWV 1060

| ||

| 1. Allegro | 2. Adagio | 3. Allegro |

Scoring: harpsichord I/II solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

Length: c. 14 minutes

While the existing score is in the form of a concerto for harpsichords and strings, Bach scholars believe it to be a transcription of a lost double concerto in D minor; a reconstructed arrangement of this concerto for two violins or violin and oboe is classified as BWV 1060R.[46] The subtle and masterful way in which the solo instruments blend with the orchestra marks this out as one of the most mature works of Bach's years at Köthen. The middle movement is a cantabile for the solo instruments with orchestral accompaniment.

Concerto in C major, BWV 1061

| ||

| 1. Allegro | 2. Adagio ovvero Largo | 3. Fuga |

Scoring: harpsichord I/II solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone):[47]

Length: c. 19 minutes (19m:14s) [48]

Of all Bach's harpsichord concertos, this is probably the only one that originated as a harpsichord work without orchestra.[49] The work originated as a concerto for two harpsichords unaccompanied (BWV 1061a, a.k.a. BWV 1061.1,[50] in the manner of the Italian Concerto, BWV 971), and the addition of the orchestral parts (BWV 1061, a.k.a. BWV 1061.2)[51] may not have been by Bach himself.[49] The string orchestra does not fulfill an independent role, and only appears to augment cadences; it is silent in the middle movement.[47] The harpsichords have much dialogue between themselves and play in an antiphonal manner throughout.[47]

Concerto in C minor, BWV 1062

| ||

| 1. Vivace | 2. Largo ma non tanto | 3. Allegro assai |

Scoring: harpsichord I/II solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

Length: c. 15 minutes

The well-known Double Violin Concerto in D minor, BWV 1043 is the basis of this transcription. It was transposed down a tone for the same reason as BWV 1054, so that the top note would be D6.

Concertos for three harpsichords

Concerto in D minor, BWV 1063

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Concerto for Three Harpsichords No. 1 in D minor, BWV 1063 Concerto for Three Harpsichords No. 2 in C major, BWV 1064 Concerto for Four Harpsichords in A minor, BWV 1065 performed by Rolf Reinhardt and the Pro Musica Orchestra Stuttgart in 1954 Here on archive.org |

| ||

| 1. [no tempo indication] | 2. Alla Siciliana | 3. Allegro |

Scoring: harpsichord I/II/III solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

Length: c. 14 minutes

Scholars have yet to settle on the probable scoring and tonality of the concerto on which this was based, though they do think it is, like the others, a transcription.[who?]

Bach's sons may have been involved in the composition of this work. They may have also been involved in the performances of this particular concerto, as Friedrich Konrad Griepenkerl wrote in the foreword to the first edition that was published in 1845 that the work owed its existence "presumably to the fact that the father wanted to give his two eldest sons, W. Friedemann and C.Ph. Emanuel Bach, an opportunity to exercise themselves in all kinds of playing." It is believed to have been composed by 1733 at the latest.[52]

In the mid-nineteenth century the concerto, advertised as Bach's "triple concerto", became part of the concert repertoire of Felix Mendelssohn and his circle. In May 1837, Ignaz Moscheles performed it for the first time in the UK, with Sigismond Thalberg and Julius Benedict in his own concert at the King's Theatre. Instead of performing the triple concerto on harpsichords, the performed it instead on three Erard grand pianofortes. In 1840, Mendelssohn performed it with Franz Liszt and Ferdinand Hiller at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig, where he was director. The programme also included Schubert's "Great" C Major Symphony and some of his own orchestral and choral compositions; Robert Schumann described the concert as "three joyous hours of music such as one does not experience otherwise for years at a time." The concerto was repeated later in the season with Clara Schumann and Moscheles as the other soloists. Mendelssohn also played the concerto in 1844 in the Hanover Square Rooms in London with Moscheles and Thalberg. Charles Edward Horsley recalled Mendelssohn's "electrical" cadenza in a memoire of 1872 as "the most perfect inspiration, which neither before nor since that memorable Thursday afternoon has ever been approached." Moscheles had previously performed the concerto in 1842 at Gresham College in the East End of London with different soloists. After a performance in Dresden in 1845 with Clara Schumann and Hiller, Moscheles recorded in his diary, "My concert today was beyond all measure brilliant ... Bach's Triple Concerto made a great sensation; Madame Schumann played a Cadenza composed by me, Hiller and I extemporized ours."[53]

Concerto in C major, BWV 1064

| ||

| 1. Allegro | 2. Adagio | 3. Allegro assai |

Scoring: harpsichord I/II/III solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)

Length: c. 17 minutes

This concerto was probably based on an original in D major for three violins. A reconstructed arrangement of this concerto for three violins in D major is classified as BWV 1064R. In both forms this concerto shows some similarity to the concerto for two violins/harpsichords, BWV 1043/1062, in the interaction of the concertino group with the ripieno and in the cantabile slow movement.

Concerto in A minor for four harpsichords, BWV 1065

- Allegro

- Largo

- Allegro

Scoring: harpsichord I/II/III/IV solo, violin I/II, viola, continuo (cello, violone)[citation needed]

Length: c. 10 minutes[54]

Bach made a number of transcriptions of Antonio Vivaldi's concertos, especially from his Op. 3 set, entitled L'estro armonico. Bach adapted them for solo harpsichord and solo organ, but for the Concerto for 4 violins in B minor, Op. 3 No. 10, RV 580, he decided upon the unique solution of using four harpsichords and orchestra. This is thus the only orchestral harpsichord concerto by Bach which was not an adaptation of his own material.[citation needed]

The concerto for four harpsichords, strings, and continuo, BWV 1065, was the last of six known transcriptions Bach realised after concertos in Vivaldi's Op. 3. That opus, published in 1711, contains twelve concertos for strings, four of which (Nos. 3, 6, 9 and 12) have a single violin soloist. The accompaniment in these four concertos consists of violins (three parts), violas (two parts), cellos and continuo (figured bass part for violone and harpsichord). Most likely in the period from July 1713 to July 1714, during his tenure as court organist in Weimar, Bach transcribed three of these violin concertos, Nos. 3, 9 and 12, for solo harpsichord (BWV 978, 972 and 976 respectively). Similarly, in the same period, he transcribed two (Nos. 8 and 11) of the four concertos for two violins (Nos. 2, 5, 8 and 11), for unaccompanied organ (BWV 593 and 596). Vivaldi's Op. 3 also contained four concertos for four violins (Nos. 1, 4, 7 and 10). Some two decades after the over twenty Weimar concerto transcriptions for unaccompanied keyboard instruments, Bach returned to L'estro armonico, and transcribed its No. 10, the concerto in B minor for four violins, cello, strings, and continuo, RV 580, to his concerto in A minor for four harpsichords, strings and continuo, BWV 1065.[55]

| No. | RV | Key | Obligato instr. | BWV | Transcribed for | Key |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 310 | G major | violin | 978 | harpsichord | F major |

| 8 | 522 | A minor | two violins | 593 | organ (or Pedal harpsichord) | A minor |

| 9 | 230 | D major | violin | 972 | harpsichord | D major |

| 10 | 580 | B minor | four violins and cello | 1065 | four harpsichords, strings and continuo | A minor |

| 11 | 565 | D minor | two violins and cello | 596 | organ (or pedal harpsichord) | D minor |

| 12 | 265 | E major | violin | 976 | harpsichord | C major |

RV 580 was published with the same eight parts as the other concertos in L'estro armonico: four violin parts, two viola parts, cello and continuo. The differences in instrumentation between the individual concertos in Vivaldi's Op. 3 only concern which of these eight parts get soloist roles (indicated as obligato in the original publication), and which are accompaniment (ripieno parts, and continuo). For RV 580 the obligato parts are all four violin parts, and the cello part.[55]

In the middle movement, Bach has the four harpsichords playing differently-articulated arpeggios in a very unusual tonal blend, while providing some additional virtuosity and tension in the other movements.[citation needed]

Concertos for harpsichord, flute, and violin

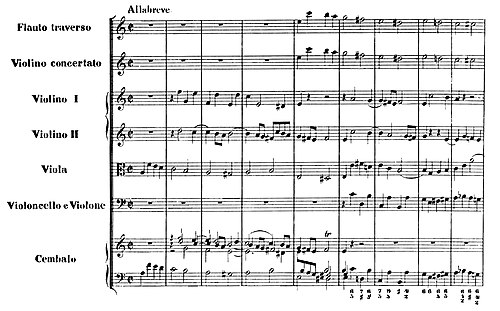

Concerto in A minor, BWV 1044

- Allegro

- Adagio ma non tanto e dolce

- Alla breve

Concertino: harpsichord, flute, violin

Ripieno: violin, viola, cello, violone, (harpsichord)

In this concerto for harpsichord, flute and violin, occasionally referred to as Bach's "triple concerto", the harpsichord has the most prominent role and greatest quantity of material. Except for an additional ripieno violin part, the instrumentation in all three movements is identical to that of Brandenburg Concerto No.5 in D major, BWV 1050. Arranged from previous compositions, the concerto is generally considered to date from the period 1729–1741 when Bach was director of the Collegium Musicum in Leipzig and was responsible for mounting weekly concerts of chamber and orchestral music in the Café Zimmermann. Wollny (1997) and Wolff (2007) contain a comprehensive discussion of the concerto, including its history and questions of authenticity. Because one of the earliest surviving manuscripts comes from the library of Frederick the Great and because of post-baroque galant aspects of the instrumental writing—fine gradations in the dynamical markings (pp, p, mp, mf, f), the wider range of the harpsichord part as well as frequent changes between pizzicato and arco in the strings—Wollny has suggested that the arrangement as a concerto might have been intended for Frederick, a keen flautist who employed Bach's son Carl Philipp Emanuel as court harpsichordist; this could imply a later date of composition. Some commentators have questioned the authenticity of the work, although it is now generally accepted.[57][58][59]

The concerto is an example of the "parody technique"—the reworking in new forms of earlier compositions—that Bach practised increasingly in his later years.[60] The first and third movements are adapted from the prelude and fugue in A minor for harpsichord, BWV 894, a large scale work from Bach's period in Weimar:[61]

The prelude and fugue have the structure of the first and last movements of an Italian concerto grosso, which has led to suggestions that they might be transcriptions of a lost instrumental work. In the concerto BWV 1044, Bach reworked both the prelude and fugue around the harpsichord part by adding ripieno ritornello sections.[62] In the first movement there is an eight bar ritornello that begins with the opening semiquaver motif of the prelude, which is then heard in augmented form before breaking into distinctive triplet figures:

This newly composed material, which recurs throughout the movement, creates a contrast with that of the soloists, much of which is directly drawn from the original prelude, especially the harpsichord part. Like the first movement of Brandenburg Concerto No. 5, the virtuosic harpsichord part takes precedence, with some passages from the original extended, some played solo and some omitted. In the solo episodes the flute and violin provide a "small ripieno" accompaniment to the harpsichord, contrasting with the "large ripieno" of the orchestral strings in the tutti sections.[63]

The last movement of the concerto begins with a fugue subject in crotchets and minims in the viola and the bass line of the harpsichord and a countersubject which provides the material for the orchestral ritornello and transforms the original fugue BWV 894/2 into a triple fugue:

At bar 25 the harpsichord enters with the main fugue subject from BWV 894/2—a moto perpetuo in triplets—overlaid by the countersubject of the ritornello.

The fugue subject in the ritornello is "hidden" in the main fugue subject ("soggetto cavato dalle note del tema"): its constituent notes—A, F, E, D, C, B, A, G♯, A, B—can be picked out in each of the corresponding crotchet and minim groups of triplets in the main subject. Other departures from BWV 894/2 include a number of virtuosic passages in the harpsichord, with demisemiquaver runs, semiquavers in the triplets and finally semiquavers replacing the triplets, culminating in a cadenza for the harpsichord.[64]

The middle movement is a reworking and transposition of material from the slow movement of the sonata for organ in D minor, BWV 527; both movements are thought to be based on a prior lost composition. Like the slow movement of the fifth Brandenburg Concerto, the slow movement of BWV 1044 is scored as a chamber work for the solo instruments. In binary form, the harpsichord alternates in repeats between upper and lower keyboard parts of BWV 527/2; the other melodic keyboard part is played alternately by flute or violin, while the other instrument adds a fragmentary accompaniment in semiquavers (scored as pizzicato for the violin).

As Mann (1989) comments, Bach's son Carl Philipp Emanuel related to his biographer Johann Nikolaus Forkel how his father took pleasure in converting trios into quartets ex tempore ("aus dem Stegereif"): BWV 1044/2 is a prime example. Bach created a complex texture in this movement by juxtaposing the detached melody in the harpsichord with a parallel sustained melody in thirds or sixths in the violin or flute; and in contrast a further layer is added by the delicate pizzicato accompaniment in the fourth voice, —first in the violin and then echoed by the flute—which comes close to imitating the timbre of the harpsichord.[60]

Concerto in D major, BWV 1050 (Brandenburg Concerto No. 5)

- Allegro

- Affettuoso

- Allegro

Concertino: harpsichord, violin, flute[65]

Ripieno: violin, viola, cello, violone, (harpsichord)

The harpsichord is both a concertino and a ripieno instrument: in the concertino passages the part is obbligato; in the ripieno passages it has a figured bass part and plays continuo.

This concerto makes use of a popular chamber music ensemble of the time (flute, violin, and harpsichord), which Bach used on their own for the middle movement. It is believed that it was written in 1719, to show off a new harpsichord by Michael Mietke which Bach had brought back from Berlin for the Cöthen court. It is also thought that Bach wrote it for a competition at Dresden with the French composer and organist Louis Marchand; in the central movement, Bach uses one of Marchand's themes. Marchand fled before the competition could take place, apparently scared off in the face of Bach's great reputation for virtuosity and improvisation.

The concerto is well suited throughout to showing off the qualities of a fine harpsichord and the virtuosity of its player, but especially in the lengthy solo 'cadenza' to the first movement. It seems almost certain that Bach, considered a great organ and harpsichord virtuoso, was the harpsichord soloist at the premiere. Scholars have seen in this work the origins of the solo keyboard concerto as it is the first example of a concerto with a solo keyboard part.[66][67]

An earlier version, BWV 1050a, has innumerable small differences from its later cousin, but only two main ones: there is no part for cello, and there is a shorter and less elaborate (though harmonically remarkable) harpsichord cadenza in the first movement. (The cello part in BWV 1050, when it differs from the violone part, doubles the left hand of the harpsichord.)

Recordings

BWV 1052–1065 set

- Trevor Pinnock, Kenneth Gilbert, Lars Ulrik Mortensen, Nicholas Kraemer, The English Concert, Trevor Pinnock; 1981; Archiv Produktion 471754-2 (2002 re-issue)

- Andras Schiff, Peter Serkin, Bruno Canino (pianos), Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Camerata Bern; 1990, 1993, 1997; Decca Records 4782363 (this 4CD-set also includes BWV 971, BWV 1044 with Aurélie Nicolet (flute) and Yuuko Shiokawa (violin); does not include BWV 1065)

- Ton Koopman, The Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra; 1991; Erato 91929 & 91930 (these two 2CD-sets also include BWV 1044 with Wilbert Hazelzet (flute) and Andrew Manze (violin); the 2nd, 3rd and 4th harpsichord parts are performed by Tini Mathot, Patrizia Marisaldi and Elina Mustonen respectively)

BWV 1052–1058 set

Solo part performed on harpsichord, unless otherwise indicated:

- Igor Kipnis, The London Strings, Neville Marriner; 1971; CBS Masterworks Records M2YK 45616

- Andrei Gavrilov (piano), Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, Neville Marriner; 1987; EMI Classics 573641-2 (1999 re-issue)

- Christine Schornsheim, Neues Bachisches Collegium Musicum, Burkhard Glaetzner; 1990-1992; Brilliant Classics 99360/6 and /7

- Murray Perahia (piano & conductor), Academy of St. Martin in the Fields; 2000-2001; Sony Classical SK89245 / SK89690

- Angela Hewitt (piano), Australian Chamber Orchestra, Richard Tognetti (violin); 2005; Hyperion CDA67607/8 (this 2CD-set also includes BWV 1044 and BWV 1050 with Richard Tognetti (violin) and Alison Mitchell (flute))

- Andreas Staier, Freiburger Barockorchester; 2013; Harmonia Mundi HMC 902181.82

BWV 1059

Salvatore Carchiolo reconstruction (BWV 35, solo parts for harpsichord and oboe):

- Salvatore Carchiolo, Andrea Mion, Insieme Strumentale di Roma, Giorgio Sasso; 2011; Brilliant Classics 94340

Masato Suzuki reconstruction:

- Masato Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan, BIS-2401 SACD (June 2020)[68]

Winifried Radeke reconstruction (BWV 35, solo part for flute):

- Jean-Pierre Rampal, Orchestre de chambre Jean-François Paillard, Jean-François Paillard; 1974; Erato STU 70693

- James Galway, Zagreb Soloists; 1987; RCA GD 86517

BWV 1060–1065 set

- Gustav Leonhardt, Alan Curtis, Janny van Wering, Anneke Uittenbosch, Eduard Müller, Leonhardt-Consort; 1968; Teldec 4509-97452-2

- Pieter-Jan Belder, Menno van Delft, Siebe Henstra, Vincent van Laar, Musica Amphion; 2006; Brilliant Classics 93187

- Evgeni Koroliov, Anna Vinnitskaya, Ljupka Hadzi Georgieva (pianos), Kammerakademie Potsdam; 2019; Alpha Classics 446 (2CD-set, also contains four concertos from the BWV 1052–1058 set)

Notes

- ^ The manuscript bears the watermark of Frederick the Great. Acquired by the Sing Akademie in Berlin, the title page was written by its director Carl Friedrich Zelter who noted in pencil that the harpsichord part had been lent to the harpsichordist Sara Levy, great aunt of Felix Mendelssohn, on 29 May 1831[56]

References

- ^ Rampe 2013, p. 357 The translation is taken from Spitta (1899, pp. 136–137)

- ^ a b c d e Peter Wollny, "Harpsichord Concertos," booklet notes for Andreas Staier's 2015 recording of the concertos, Harmonia Mundi HMC 902181.82

- ^ Williams 2016, pp. 264–265

- ^ Breig 1997, p. 168.

- ^ a b Butt 1999, p. 209

- ^ Rampe 2013, pp. 368–375

- ^ Williams 2016, p. 269

- ^ Williams 2016, pp. 368–369

- ^ Williams 2016, pp. 365–366

- ^ a b Wolff 2016, pp. 60–75

- ^ Butler 2016, pp. 76–86.

- ^ See:

- Wolff 2008

- Wolff 2016

- Rampe 2014

- Williams 2016, pp. 370–371, 376

- ^ Wolff (2016, p. 66)

- ^ Pieter Dirksen. "The Background to Bach's Fifth Brandenburg Concerto" pp. 157–185 in The Harpsichord and its Repertoire: Proceedings of the International Harpsichord Symposium, Utrecht, 1990. Utrecht: STIMU Foundation for Historical Performance Practice, 1992. ISBN 90-72786-03-3

- ^ a b c Breig 1997, pp. 167ff.

- ^ Rampe 2013, pp. 368–375.

- ^ Cantagrel 1993.

- ^ Butt 1999, p. 210.

- ^ Rampe 2013, pp. 264–270, 372–375.

- ^ Wolff 2016, p. 67.

- ^ a b Wolff 2016.

- ^ Butler 2016.

- ^ Wollny 2015, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jones 2013, pp. 258–259, 267.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rampe 2013, pp. 268–270.

- ^ Rampe 2013, p. 272.

- ^ a b Wolff 2005.

- ^ Kroll 2014, p. 264

- ^ Alfred Dörffel. "Statistik der Concerte im Saale des Gewandhauses zu Leipzig" p. 3, in Geschichte der Gewandhausconcerte zu Leipzig vom 25. November 1781 bis 25. November 1881: Im Auftrage der Concert-Direction verfasst. Leipzig, 1884.

- ^ a b c d e Kroll 2014, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Schneider 1907, p. 102.

- ^ Basso 1979, p. 68.

- ^ Platt 2012, pp. 270, 548.

- ^ Rampe & Sackmann 2000.

- ^ a b Siegele 1957.

- ^ a b Dirksen 2008

- ^ Wolff, Christoph (2007). Johann Sebastian Bach (2nd ed.). Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer. ISBN 978-3-596-16739-5.

- ^ a b Kroll 2014, p. p. 268

- ^ Tovey 1935.

- ^ Wilfried Fischer, Kompositionsweise und Bearbeitungstechnik in der Instrumentalmusik Johann Sebastian Bachs, Neuhausen Stuttgart: Hänssler-Verlag 1975

- ^ Mohr 1972, pp. 507–508.

- ^ Steven Zohn, Music for a Mixed Taste: Style, Genre, and Meaning in Telemann's Instrumental Works, Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 192–194, ISBN 978-0-19-516977-5

- ^ "Hannah and Her Sisters Original Soundtrack". Allmusic. Retrieved 2024-11-03.

- ^ Uwe Kraemer. Liner notes for Bach: The Harpsichord Concertos (Igor Kipnis, The London Strings, Neville Marriner) CBS Records M2YK 45616, 1989.

- ^ Rampe 2013, pp. 390–396.

- ^ Butt 1999.

- ^ a b c Jones 2013, pp. 254–256

- ^ Schnabel, Artur; Schnabel, Karl Ulrich (1951). "Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra in C major, BWV 1061, by J.S. Bach". British Library.

- ^ a b Jones 2013, p. 255, footnote 18

- ^ "Concerto, C (version for two solo harpsichords) BWV 1061.1; BWV 1061a". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 2020-04-16.

- ^ "Concerto, C (version for 2 harpsichords, strings and basso continuo) BWV 1061.2; BWV 1061". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 2020-04-16.

- ^ Bach: The Concertos for 3 and 4 Harpsichords – Trevor Pinnock and the English Concert, from the CD booklet written by Dr. Werner Breig, 1981, Archive Produktion (bar code 3-259140-004127)

- ^ See:

- Mercer-Taylor, Peter (2000), The Life of Mendelssohn, Cambridge University Press, p. 144, ISBN 0-521-63972-7

- Eatock, Colin (2009), Mendelssohn and Victorian England, Ashgate, p. 86, ISBN 978-0-7546-6652-3

- Kroll 2014, p. 268

- ^ Bach - Concerto in A minor BWV 1065 | Netherlands Bach Society on YouTube

- ^ a b H. Joseph Butler. "Emulation and Inspiration: J. S. Bach’s Transcriptions from Vivaldi’s L’estro armonico" in The Diapason, August 2011.

- ^ See:

- Wollny 1993, p. 681

- Wollny 1997, p. 283

- ^ Jones 2013, p. 395.

- ^ Rampe 2013.

- ^ See:

- Wolff 1985

- Kilian 1989, pp. 47–48

- Schulenberg 1995, p. 30

- Wollny 1997, pp. 283–285

- ^ a b Mann 1989

- ^ For a detailed discussion of BWV 849, see Schulenberg (2006, pp. 145–146)

- ^ Jones 2013, p. 395

- ^ See:

- Mann 1989, p. 116

- Wollny 1997, p. 285

- ^ See:

- Mann 1989, pp. 116–117

- Abravaya 2006, pp. 61–64

- ^ Dirksen 1992.

- ^ Steinberg, M. The Concerto: A Listener's Guide, p. 14, Oxford (1998) ISBN 0-19-513931-3

- ^ Hutchings, A. 1997. A Companion to Mozart's Piano Concertos, p. 26, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816708-3

- ^ J. S. Bach - Concertos for Harpsichord, Vol. 1 at BIS website.

Sources

- Abravaya, Ido (2006), On Bach's Rhythm and Tempo (PDF), Bochumer Arbeiten zur Musikwissenschaft, vol. 4, Bärenreiter, ISBN 3-7618-1602-2

- Basso, Alberto (1979). Frau Musika: La vita e le opere di J. S. Bach (in Italian). Vol. Le origini familiari, l'ambiente luterano, gli anni giovanili, Weimar e Köthen (1685–1723). Turin: EDT. ISBN 88-7063-011-0.

- Breig, Werner (1997). "The instrumental music" and "Composition as Arrangement and Adaptation". In Butt, John (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Bach. Cambridge Companions to Music. Translated by Spencer, Steward. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123–135 and 154–170. ISBN 0-521-58780-8.

- Butler, Gregory (2016), "The Choir Loft as Chamber: Concerted Movements by Bach from the Mid- to Late 1720s", in Matthew Dirst (ed.), Bach Perspectives, Volume 10, Bach and the Organ, University of Illinois Press, pp. 76–86, ISBN 978-0-252-04019-1

- Butt, John (1999). "Harpsichord Concertos". In Boyd, Malcolm; Butt, John (eds.). J. S. Bach. Oxford Composer Companions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866208-2.

- Cantagrel, Gilles (1993). "Sur les traces de l'oeuvre pour orgue et orchestre de J. S. Bach". Johann Sebastian Bach: L'oeuvre pour orgue et orchestre (liner notes). André Isoir (organ) and Le Parlement de Musique conducted by Martin Gester. Calliope. CAL 9720.

- Dirksen, Pieter [in Dutch] (1992). "The Background to Bach's Fifth Brandenburg Concerto". The Harpsichord and its Repertoire: Proceedings of the International Harpsichord Symposium, Utrecht, 1990. Utrecht: STIMU Foundation for Historical Performance Practice. pp. 157–185. ISBN 90-72786-03-3.

- Dirksen, Pieter (2008), "J. S. Bach's Violin Concerto in G Minor", in Gregory Butler (ed.), J. S. Bach's Concerted Ensemble Music: The Concerto, Bach Perspectives, vol. 7, University of Illinois Press, p. 21, ISBN 978-0-252-03165-6

- Jones, Richard D. P. (2013), The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume II: 1717–1750: Music to Delight the Spirit, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-969628-4

- Kilian, Dietrich (1989), Johann Sebastian Bach, Concertos for Violin, for two Violins, for Harpsichord, Flute and Violin, Critical Commentary, Neue Bach Ausgabe (in German), vol. III, Bärenreiter

- Kroll, Mark (2014), Ignaz Moscheles and the Changing World of Musical Europe, Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-1-84383-935-4

- Mann, Alfred (1989), "Bach's parody technique and its frontiers", in Don O. Franklin (ed.), Bach Studies 1, CUP Archive, pp. 115–117, ISBN 0-521-34105-1

- Mohr, Wilhelm (1972), "Hat Bach ein Oboe-d'amore-Konzert geschrieben?", Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, 133: 507–508

- Platt, Heather (2012). Johannes Brahms: A Research and Information Guide (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-84708-1.

- Rampe, Siegbert; Sackmann, Dominik (2000), Bachs Orchestermusik (in German), Kassel: Bärenreiter, ISBN 3-7618-1345-7

- Rampe, Siegbert (2013), Bachs Orchester- und Kammermusik, Bach-Handbuch (in German), vol. 5/1, Laaber-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-89007-455-9

- Rampe, Siegbert (2014), "Hat Bach Konzerte für Orgel und Orchester komponiert?" (PDF), Musik & Gottesdienst (in German), 68: 14–22, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-27, retrieved 2016-11-27

- Schneider, Max [in German] (1907). "Verzeichnis der bis zum Jahre 1851 gedruckten (und der geschrieben im Handel gewesenen) Werke von Johann Sebastian Bach". Bach-Jahrbuch 1906. Bach-Jahrbuch (in German). Breitkopf & Härtel. pp. 84–113.

- Schulenberg, David (1995), "Composition and Improvisation in the School of J. S. Bach", in Russell Stinson (ed.), Bach Perspectives 1, University of Nebraska Press, pp. 1–42, ISBN 0-8032-1042-6

- Schulenberg, David (2006), The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-97400-3

- Siegele, Ulrich (1957), Kompositionsweise und Bearbeitungstechnik in der Instrumentalmusik Johann Sebastian Bachs (dissertation) (in German), Hänssler, ISBN 3-7751-0117-9

- Spitta, Philipp (1899), Johann Sebastian Bach; his work and influence on the music of Germany, 1685–1750, Volume 3, translated by Clara Bell; J. A. Fuller-Maitland, Novello

- Williams, Peter (2016), Bach: A Musical Biography, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-13925-1

- Tovey, Donald Francis (1935), "Concerto in A major for Oboe d'amore with strings and continuo", Essays in Musical Analysis, vol. II, London: Oxford University Press, pp. 196–198

- Wolff, Christoph (1985), "Bach's Leipzig chamber music", Early Music, 13 (2): 165–175, doi:10.1093/earlyj/13.2.165

- Wolff, Christoph (2005). "A Bach Cult in Late-Eighteenth-Century Berlin: Sara Levy's Musical Salon" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Academy (Spring). American Academy of Arts and Sciences: 26–31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- Wolff, Christoph (2008), "Sicilianos and Organ Recitals: Observations on J. S. Bach's concertos", in Gregory Butler (ed.), J. S. Bach's Concerted Ensemble Music: The Concerto, Bach Perspectives, vol. 7, University of Illinois Press, pp. 97–114, ISBN 978-0-252-03165-6

- Wolff, Christoph (2016), "Did J. S. Bach Write Organ Concertos? Apropos the Prehistory of Cantata Movements with Obbligato Organ", in Dirst, Matthew (ed.), Bach and the Organ, Bach Perspectives, vol. 10, University of Illinois Press, pp. 60–75, ISBN 978-0-252-04019-1, JSTOR 10.5406/j.ctt18j8xkb.8

- Wollny, Peter (1993), "Sara Levy and the Making of Musical Taste in Berlin", The Musical Quarterly, 77 (4): 651–688, doi:10.1093/mq/77.4.651, JSTOR 742352

- Wollny, Peter (1997), "Uberlegungen zum Tripelkonzert a-Moll (BWV 1044)", in Martin Geck; Werner Breig (eds.), Bachs Orchesterwerke: Bericht über das 1. Dortmunder Bach-Symposion im Januar 1996, Dortmund: Klangfarben Musikverlag, pp. 283–291

- Wollny, Peter (2015). "Harpsichord Concertos". Johann Sebastian Bach: Harpsichord Concertos (PDF) (liner notes). Andreas Staier, Freiburger Barockorchester. Harmonia Mundi. pp. 6–7. HMC 902181.82.

Further reading

- Berger, Christian (1997), "Ein Spiel mit Form-Modellen. J. S. Bachs Cembalokonzert E-Dur BWV 1053", in Martin Geck; Werner Breig (eds.), Bachs Orchesterwerke: Bericht über das 1. Dortmunder Bach-Symposion im Januar 1996 (in German), Dortmund: Klangfarben Musikverlag, pp. 257–263

- Breig, Werner (1991), "Der Ostinatoprinzip in Johann Sebastian Bachs langsamen Konzertsătzen", in Wolfgang Osthoff; Reinhard Wiesend (eds.), Von Isaac bis Bach. Festschrift Martin Just zum 60. Geburtstag, Bärenreiter, pp. 287–300

- Breig, Werner (1993), "Zur Gestalt Johann Sebastian Bachs Konzert für Oboe d'amore", Tibia, 18: 431–448

- Breig, Werner (1999). "Preface" (PDF). Bach: Concertos for Harpsichord (study score based on the urtext of the New Bach Edition). Translated by Taylor, Steve. Bärenreiter. pp. XI–XV. ISMN 9790006204519.

- Breig, Werner (2001), Johann Sebastian Bach: Concertos for Cembalo BWV 1052–1059, with critical commentary, Neue Bach Ausgabe, vol. VII/4, Bärenreiter, ISMN 9790006494699,

- Werner Breig, notes to recordings of the complete harpsichord concertos by Trevor Pinnock and The English Concert (1981, Archiv Produktion); lengths also taken from these recordings

- Butler, Gregory (1995), "J. S. Bach's reception of Tomaso Albinoni's concertos", in Daniel R. Melamed (ed.), Bach Studies 2, Cambridge University Press, pp. 20–46, ISBN 0-521-02891-4

- Butler, Gregory (2008), "Bach the Cobbler: The Origins of Bach's E-major Concerto (BWV 1053)", in Gregory Butler (ed.), J. S. Bach's Concerted Ensemble Music: The Concerto, Bach Perspectives, vol. 7, University of Illinois Press, pp. 1–20, ISBN 978-0-252-03165-6

- Dürr, Alfred (2006), The cantatas of J. S. Bach, Oxford University Press, pp. 392–397, ISBN 0-19-929776-2

- Eppstein, Hans (1970), Droysen, Dagmar (ed.), "Zur Vor- und Entstehungsgeschichte von J. S. Bachs Tripelkonzert a-Moll (BWV 1044)", Jahrbuch des Staatlichen Instituts für Musikforschung Preufßischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin: Merseburger: 34–44

- Geck, Martin (1994), "Köthen oder Leipzig? Zur Datierung der nur in Leipziger Quellen erhaltenen Orchesterwerke Johann Sebastian Bachs", Die Musikforschung, 47: 17–24, doi:10.52412/mf.1994.H1.1098, S2CID 244226070

- Haynes, Bruce (2001), The Eloquent Oboe: A History of the Hautboy 1640–1760, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-816646-7

- Jones, Richard D. P. (2007), The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume I: 1695–1717: Music to Delight the Spirit, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-816440-1

- Sackmann, Dominik (2000), Bach und Corelli: Studien zu Bachs Rezeption von Corellis Violinsonaten op. 5 unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der "Sogenannten Arnstädter Orgelchoräle" und der langsamen Konzertsätze, Musikwissenschaftliche Schriften (in German), vol. 36, Katzbichler, ISBN 3-87397-095-3

- Schmieder, Wolfgang (1998). "11. Orchesterwerke". In Dürr, Alfred; Kobayashi, Yoshitake (eds.). Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis: Kleine Ausgabe (BWV2a) (in German). Breitkopf & Härtel. pp. 424–436. ISBN 3-7651-0249-0.

- Schulze, Hans-Joachim (1981), "J. S. Bachs Konzerte: Fragen der Überlieferung und Chronologie", in P. Ahnsehl (ed.), Beiträge zum Konzertschaffen J. S. Bachs, Bach-Studien, vol. 6, Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, pp. 9–26

- Williams, Peter (1997), The Chromatic Fourth During Four Centuries of Music, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-816563-3

- Wolff, Christoph (1994), Bach: Essays on His Life and Work, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-05926-3

- Wolff, Christoph (2002), Johann Sebastian Bach: the learned musician, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924884-2

- Wollny, Peter (2010), 'Ein förmlicher Sebastian und Philipp Emanuel Bach-Kultus': Sara Levy und ihr musikalisches Wirken (in German), Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel

External links

- Autograph manuscript of BWV 1052–1059, Bach Archive, Leipzig

- Manuscript of BWV 1052a, Bach Archive, Leipzig

- Harpsichord Concerto No. 1, BWV 1052, No. 2, BWV 1053, No. 3, BWV 1054, No. 4, BWV 1055, No. 5, BWV 1056, No. 6, BWV 1057, No. 7, BWV 1058, No. 8, BWV 1059: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Concerto for Flute, Violin and Harpsichord, BWV 1044: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Concerto for 2 Harpsichords, BWV 1060, BWV 1061, BWV 1062, BWV 1063, BWV 1064, BWV 1065: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Program notes from the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra

- Concerto in G minor BWV 1058 by Jozef Kapustka and the Orquestra de Cordas da Grota (Rio de Janeiro)