In linguistics, the head or nucleus of a phrase is the word that determines the syntactic category of that phrase. For example, the head of the noun phrase "boiling hot water" is the noun (head noun) "water".

Analogously, the head of a compound is the stem that determines the semantic category of that compound. For example, the head of the compound noun "handbag" is "bag", since a handbag is a bag, not a hand.

The other elements of the phrase or compound modify the head, and are therefore the head's dependents.[1] Headed phrases and compounds are called endocentric, whereas exocentric ("headless") phrases and compounds (if they exist) lack a clear head.

Heads are crucial to establishing the direction of branching. Head-initial phrases are right-branching, head-final phrases are left-branching, and head-medial phrases combine left- and right-branching.

Basic examples

Examine the following expressions:

- big red dog

- birdsong

The word dog is the head of big red dog since it determines that the phrase is a noun phrase, not an adjective phrase. Because the adjectives big and red modify this head noun, they are its dependents.[2] Similarly, in the compound noun birdsong, the stem song is the head since it determines the basic meaning of the compound. The stem bird modifies this meaning and is therefore dependent on song. Birdsong is a kind of song, not a kind of bird. Conversely, a songbird is a type of bird since the stem bird is the head in this compound. The heads of phrases can often be identified by way of constituency tests. For instance, substituting a single word in place of the phrase big red dog requires the substitute to be a noun (or pronoun), not an adjective.

Representing heads

Trees

Many theories of syntax represent heads by means of tree structures. These trees tend to be organized in terms of one of two relations: either in terms of the constituency relation of phrase structure grammars or the dependency relation of dependency grammars. Both relations are illustrated with the following trees:[3]

The constituency relation is shown on the left and the dependency relation on the right. The a-trees identify heads by way of category labels, whereas the b-trees use the words themselves as the labels.[4] The noun stories (N) is the head over the adjective funny (A). In the constituency trees on the left, the noun projects its category status up to the mother node, so that the entire phrase is identified as a noun phrase (NP). In the dependency trees on the right, the noun projects only a single node, whereby this node dominates the one node that the adjective projects, a situation that also identifies the entirety as an NP. The constituency trees are structurally the same as their dependency counterparts, the only difference being that a different convention is used for marking heads and dependents. The conventions illustrated with these trees are just a couple of the various tools that grammarians employ to identify heads and dependents. While other conventions abound, they are usually similar to the ones illustrated here.

More trees

The four trees above show a head-final structure. The following trees illustrate head-final structures further as well as head-initial and head-medial structures. The constituency trees (= a-trees) appear on the left, and dependency trees (= b-trees) on the right. Henceforth the convention is employed where the words appear as the labels on the nodes. The next four trees are additional examples of head-final phrases:

The following six trees illustrate head-initial phrases:

And the following six trees are examples of head-medial phrases:

The head-medial constituency trees here assume a more traditional n-ary branching analysis. Since some prominent phrase structure grammars (e.g. most work in Government and binding theory and the Minimalist Program) take all branching to be binary, these head-medial a-trees may be controversial.

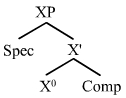

X-bar trees

Trees that are based on the X-bar schema also acknowledge head-initial, head-final, and head-medial phrases, although the depiction of heads is less direct. The standard X-bar schema for English is as follows:

This structure is both head-initial and head-final, which makes it head-medial in a sense. It is head-initial insofar as the head X0 precedes its complement, but it is head-final insofar as the projection X' of the head follows its specifier.

Head-initial vs. head-final languages

Some language typologists classify language syntax according to a head directionality parameter in word order, that is, whether a phrase is head-initial (= right-branching) or head-final (= left-branching), assuming that it has a fixed word order at all. English is more head-initial than head-final, as illustrated with the following dependency tree of the first sentence of Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis:

The tree shows the extent to which English is primarily a head-initial language. On the broadest level, the verb phrase "discovered that he had been changed into a monstrous verminous bug" begins with the verb headword "discovered". Structure is descending as speech and processing move (visually in writing) from left to right. Most dependencies have the head preceding its dependent(s), although there are also head-final dependencies in the tree. For instance, the determiner-noun and adjective-noun dependencies are head-final as well as the subject-verb dependencies. Most other dependencies in English are, however, head-initial as the tree shows. The mixed nature of head-initial and head-final structures is common across languages. In fact purely head-initial or purely head-final languages probably do not exist, although there are some languages that approach purity in this respect, for instance Japanese.

The following tree is of the same sentence from Kafka's story. The glossing conventions are those established by Lehmann. One can easily see the extent to which Japanese is head-final:

A large majority of head-dependent orderings in Japanese are head-final. This fact is obvious in this tree, since structure is strongly ascending as speech and processing move from left to right. Thus the word order of Japanese is in a sense the opposite of English.

Head-marking vs. dependent-marking

It is also common to classify language morphology according to whether a phrase is head-marking or dependent-marking. A given dependency is head-marking, if something about the dependent influences the form of the head, and a given dependency is dependent-marking, if something about the head influences the form of the dependent.

For instance, in the English possessive case, possessive marking ('s) appears on the dependent (the possessor), whereas in Hungarian possessive marking appears on the head noun:[5]

| English: | the man's house | |

| Hungarian: | az ember ház-a (the man house-POSSESSIVE) |

Prosodic head

In a prosodic unit, the head is the part that extends from the first stressed syllable up to (but not including) the tonic syllable. A high head is the stressed syllable that begins the head and is high in pitch, usually higher than the beginning pitch of the tone on the tonic syllable. For example:

The ↑bus was late.

A low head is the syllable that begins the head and is low in pitch, usually lower than the beginning pitch of the tone on the tonic syllable.

The ↓bus was late.

See also

Notes

- ^ For a good general discussion of heads, see Miller (2011:41ff.). However, take note Miller miscites Hudson's (1990) listing of Zwicky's criteria of headhood as if these were Matthews'.

- ^ Discerning heads from dependents is not always easy. The exact criteria that one employs to identify the head of a phrase vary, and definitions of "head" have been debated in detail. See the exchange between Zwicky (1985, 1993) and Hudson (1987) in this regard.

- ^ Dependency grammar trees similar to the ones produced in this article can be found, for instance, in Ágel et al. (2003/6).

- ^ Using the words themselves as the labels on the nodes in trees is a convention that is consistent with bare phrase structure (BPS). See Chomsky (1995).

- ^ See Nichols (1986).

References

- Chomsky, N. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Corbett, G., N. Fraser, and S. McGlashan (eds). 1993. Heads in Grammatical Theory. Cambridge University Press.

- Hudson, R. A. 1987. Zwicky on heads. Journal of Linguistics 23, 109–132.

- Miller, J. 2011. A critical introduction to syntax. London: Continuum.

- Nichols, J. 1986. Head-marking and dependent-marking grammar. Language 62, 56-119.

- Zwicky, A. 1985. Heads. Journal of Linguistics 21, pp. 1–29.

- Zwicky, A. 1993. Heads, bases and functors. In G. Corbett, et al. (eds) 1993, 292–315.