Hilarión Daza | |

|---|---|

| |

| 19th President of Bolivia | |

| In office 4 May 1876 – 28 December 1879 | |

| Preceded by | Tomás Frías |

| Succeeded by | Pedro José de Guerra (acting) Uladislao Silva (President of the Junta) Narciso Campero (provisional) |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 13 May 1874 – 14 February 1876 | |

| President | Tomás Frías |

| Preceded by | Ildefonso Sanjinés |

| Succeeded by | Eliodoro Camacho |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hilarión Grosolí Daza 14 January 1840 Sucre, Bolivia |

| Died | 27 February 1894 (aged 54) Uyuni, Bolivia |

| Manner of death | Assassination |

| Spouse | Benita Gutiérrez |

| Children | Raquel Daza Gutiérrez |

| Parent(s) | Marcos Groselle Juana Daza |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Bolivian Army |

| Rank | General |

Hilarión Daza (born Hilarión Grosolí Daza; 14 January 1840 – 27 February 1894) was a Bolivian military officer who served as the 19th president of Bolivia from 1876 to 1879. During his presidency, the infamous War of the Pacific started, a conflict which proved to be devastating for Bolivia.

Life before the presidency

Early life and family

Daza was born in the city of Sucre on January 14, 1840. His father, Marcos Groselle, was originally from Piedmont, Italy —his surname was Grosoli, later transformed into Groselle—, while his mother, Juana Daza of mestizo origin. Daza changed his surname to his mother's in order to fit in better into Bolivian society.[1][2]

Daza entered the military career at a very young age in the 1850s, where he performed remarkably well. Gifted with exceptional willpower and skill.[3]

Military and political career

Initially, Daza was a supporter of President Mariano Melgarejo (1864-1871). However, in 1870, he began his political career by revolting against his protector, Melgarejo, betraying him for 10,000 pesos.[3] He rose to prominence under Agustín Morales, under whose government (1871-1872) he assumed command of the famous Colorados Battalion.[4] The Colorados were a unit which were supposed to physically protect the President of Bolivia, essentially serving as bodyguards. However, they were trained soldiers and feared, for they were very well trained and skilled in combat. Thereafter, the Colorados remained loyal to Daza and would help him ruse to power.[5]

After the assassination of President Morales in November 1872, he temporarily assumed power, later transferring it to Tomás Frías, who was the legal successor since he was president of the Council of State. Later, he supported the government of Adolfo Ballivián (1873-1874) and when he died, he supported Frías who assumed the presidency after the sudden death of his predecessor. It was under Frías that Daza served as Minister of War.[6]

Presidency

Coup against Frías and struggles

Once promoted to the rank of army general, in 1876, Daza revolted against President Frías, whom he overthrew, and then dictatorially assumed power. He was confirmed as Provisional President by the Constituent Assembly of 1878, approving by law the acts of his provisional government.[7] With the support of his Colorados Battalion, he imposed his authority, severely repressing the slightest opposition to his government. Daza hoped to gather the support of nationalist Bolivians to strengthen his internal position from insurrections, a massive demonstration by artisans in Sucre, and widespread opposition.[8]

Tension with the Chileans

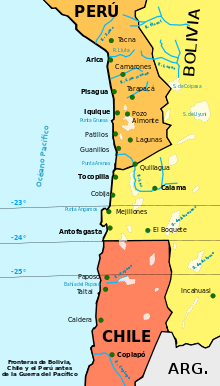

To a large extent, Daza Groselle entered the Palacio Quemado with a desire to create Bolivian control over the remote, sparsely-populated maritime province of Litoral. By the late 1870s, the latter was already settled mostly by Chileans, who found access to the region much easier than did the highland Bolivians. Predictably, a corollary of this growing physical and economic Chilean presence in the region was its irredentist claim by Santiago, especially when rich deposits of guano were discovered near the Bolivian port of Mejillones. In 1878, there was a very strong earthquake in Bolivia followed by a severe drought that caused a famine.[9]

The conflict with Chile had its genesis in the Chilean influence in the territory of the Bolivian coast, whose attraction was in guano and saltpeter. The Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta, a company with Chilean capital, had many prominent political shareholders of that country. Daza, once in power, initiated a completely anti-Chilean policy. Chileans residing in Antofagasta complained of mistreatment by the Bolivian authorities.[10]

The treaty with he Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta

In 1873, the Bolivian government signed an agreement with the representative of the Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta, an agreement that at the beginning of 1878 was not yet in force, because, according to the Bolivian constitution, contracts on natural resources had to be approved by congress. This was done by the Bolivian National Constituent Assembly through a law, on February 14, 1878, on the condition that a tax of 10 cents per quintal of saltpeter exported by the company be paid.[11]

For Chile, the collection of the tax of 10 cents per quintal exported explicitly violated article IV of the 1874 Treaty between Bolivia and Chile, which prohibited raising taxes for twenty-five years on "Chilean people, industries and capital working between parallels 23 º and 24º" and residents in that area.[12] Bolivia counterargued that the company was not a "Chilean citizen" nor a resident but a commercial entity, which constituted, according to the laws of Bolivia, as subject, therefore, to its ius imperium.[13] The Chilean owners of the affected company flatly refused to pay said tax, considering it to be abusive, and requested help from the government of Chile. Santiago pledged their support for the company's cause, despite the fact that it was a dispute between a private company and the Bolivian State.[3]

The Chilean government considered it a bilateral case and endorsed the sui generis of the conflict. Thus, began the diplomatic conflict between Bolivia and Chile that escalated rapidly in magnitude given the lack of diplomatic tact of Daza's government. Peru participated as a mediator in the resulting crisis, deciding to send a Special Ambassador and Plenipotentiary to Santiago to try to avoid a possible war through negotiation. The treaty indicated that the controversies that give rise to "the intelligence and execution of the Treaty" should be submitted to arbitration.[9][13]

The occupation of Antofagasta

On November 17, 1878, the government of La Paz ordered the prefect of the department of Cobija, Severino Zapata, to enforce the 10-cent tax established by the Law of February 14, 1878 in an attempt to counteract the serious economic crisis in Bolivia. Thus, originating the casus belli. Subsequently, on February 1, 1879, the government of Bolivia unilaterally rescinded the contract, suspending the effects of the law of February 14, 1878, and decided to claim the saltpeter fields occupied by the Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarriles de Antofagasta. They proceeded to auction the assets of the company in order to collect the unpaid taxes, using armed force in the process.[2][8][12] The auction was scheduled for February 14, 1879. Daza ignored the probability of Chilean retaliation. Chile occupied Antofagasta that same February 14, 1879, frustrating the auction. Daza, citing invasion as a casus belli, declared war on Chile. The secret treaty between Peru and Bolivia signed in 1873 in which former pledged to support the latter militarily in case of conflict with Chile.[11][13] Chile declared war on Bolivia on March 5, 1879, and proceeded to occupy the Bolivian coast, asserting old unresolved territorial claims regarding the coast between those parallels.[14]

The War of the Pacific

First phase: The unchallenged occupation of the Bolivian Litoral

The entire Bolivian coastline was occupied by Chilean troops, completely unchallenged by the Bolivian Army. A widely spread version of the events of the outbreak of the war affirms that Daza celebrated his birthday when Chile invaded Antofagasta. Coinciding with carnival, it is said that Daza withheld the news of the Chilean invasion so as not to interrupt the festivities.[15] However, this has never been confirmed.

Finally, on February 28, the news of the Chilean invasion was known in Bolivia. On March 1, Daza declared the breakdown of communications with Chile and the seizure of the properties of Chilean citizens with the use of force. At the same time, he claimed the support of Peru, in compliance with the Defensive Alliance Treaty signed in 1873.[11]

Second phase: Bolivian declaration of war and Peru's entrance

The Peruvian government urgently sent a diplomatic envoy to Santiago to mediate in the Chilean-Bolivian conflict. The mission was headed by José Antonio de Lavalle and arrived in Valparaíso on March 4. However, while these peace negotiations took place, Daza, in an evident attempt to make the negotiations fail and force Peru to join the conflict, declared war on Chile on March 14.[11][13][15]

On March 23, Bolivian and Chilean forces clashed in the Battle of Calama, with the Chileans taking the victory. Finally, on April 5, Chile declared war on Peru, after this country refused to remain neutral in the conflict.[13] As the war progressed, the Chileans began slowly pushing the Allied Forces to toward defeat. For this reason, in the midst of the war, Daza secretly negotiated with Chilean agents to separate Bolivia from the conflict and leave Peru to its own devices; In return, Bolivia would receive compensation for the loss of its coastline; the delivery of Tacna and Arica. These negotiations never materialized due to the disapproval of Bolivia's congress.[4][9][13]

Third phase: Supreme Commander of the Army and downfall

Daza withdrew from the position of head of state by supreme decree on April 17, 1879, in order to personally assume command of the army and march at the head of the Bolivian forces. He led them to Tacna, and after the Chilean landing in Pisagua, he marched south to support the Peruvian Army stationed in Iquique. After staying in Arica briefly, he continued marching. However, after three days of marching along the Camarones ravine, he announced to Peruvian President Mariano Ignacio Prado that his troops refused to continue due to the harsh conditions of the desert, opting to return to Arica. Daza's telegram to Prado on November 16 read, "Desert overwhelms, army refuses to move forward," verbatim.[10][11][15] This decision significantly affected the direction of the war, leaving Peru virtually alone in the conflict.

Meanwhile, the Peruvian army stationed in the port of Iquique under the command of General Juan Buendía, decided to advance inland. Buendía trusted the arrival of Daza's forces to break the Chilean lines. But the news of Daza's retreat had a tremendous demoralizing effect on the Peruvian troops, who suffered a serious defeat in San Francisco on November 19. Daza returned to Arica, where he learned of his dismissal as President of Bolivia on December 28 after to a coup d'état was staged by the military amid enormous discontent among the population over the direction of the war. He then moved to Arequipa, where he waited for his family to join him; This done, he left for Europe. Armed with considerable financial resources, having left with a portion of Bolivia's treasury,[14] he settled in Paris, France. In Bolivia, General Narciso Campero replaced Daza after playing a crucial role in the latter's ouster. A Junta was then established under the presidency of Uladislao Silva, which governed the country until the election of Campero as provisional president.

Later life and death

Return to Bolivia and assassination

After fifteen years in France, in 1893, Daza requested permission from the then Bolivian president, Mariano Baptista, to return to his country in order to defend himself against the accusations made by his enemies in the Legislative Congress.[16] In 1894, Daza arrived at the port of Antofagasta (former Bolivian territory) from where he headed to Uyuni with the hope of reaching the city of La Paz. However, he was assassinated by his guards upon his arrival at the Uyuni railway station.[2]

A legacy of speculations

Since the beginning of the 21st century, there has been a rising vindication movement for Daza, seeking to explain his murder with all kinds of speculation about the revelations (against Narciso Campero and others) that he was supposed to make in the Bolivian Congress. Authors such as José Mesa, Teresa Gisbert and Carlos Mesa Gisbert consider that Narciso Campero did not order the entry into action of his forces in Atacama in the second half of 1879 because he was in collusion with the mining businessmen headed by Aniceto Arce,[17] who they had commercial interests in partnership with Chilean investors on the Pacific coast, occupied by Chile after the military actions of March 1879. However, nothing has ever been proven.

Personal life

He married in La Paz, on October 12, 1872, with the distinguished lady Doña Benita Gutiérrez. Acting as witnesses to the marriage were Agustín Morales and Casimiro Corral, who was Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bolivia at the time. From this marriage, Doña Raquel Daza y Gutiérrez was born.

See also

References

- ^ "La Guerra del Pacífico 1879-1884 (Perú, Bolivia y Chile): General Hilarión Daza". La Guerra del Pacífico 1879-1884 (Perú, Bolivia y Chile). 7 February 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ a b c General Hilarion Daza: El crimen de Uyuni (in Spanish). Imp. de " La Tribuna". 1894.

- ^ a b c Retamoso, Enrique Vidaurre (1975). El presidente Daza (in Spanish). Biblioteca del Sesquicentenario de la República.

- ^ a b Lemoine, Joaquin (2010). Biografia del General Eliodoro Camacho (in Spanish). Read Books Design. ISBN 978-1-4465-1436-8.

- ^ House documents. 1877.

- ^ Bolivia (1874). Anuario de Leyes Y Disposiciones Supremas (in Spanish).

- ^ Bolivia (1880). Anuario de Leyes Y Disposiciones Supremas (in Spanish).

- ^ a b "Bolivia - POLITICAL INSTABILITY AND ECONOMIC DECLINE, 1839-79".

- ^ a b c Esposito, Gabriele (12 June 2018). The War of the Pacific. Winged Hussar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-945430-20-6.

- ^ a b Phillips, Richard Snyder (1989). Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. University of Virginia.

- ^ a b c d e Farcau, Bruce W. (2000). The Ten Cents War: Chile, Peru, and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96925-7.

- ^ a b Rossi, Christopher R. (27 April 2017). Sovereignty and Territorial Temptation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-18353-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Basadre, Jorge (1946). Historia de la república del Perú (in Spanish). Editorial Cultura Antártica, s. a., distribuidores exclusivos: Librería Internacional del Perú, s. a.

- ^ a b "Bolivia - FROM THE WAR OF THE PACIFIC TO THE CHACO WAR, 1879- 1935".

- ^ a b c Calvo, Roberto Querejazu (1995). Aclaraciones históricas sobre la Guerra del Pacífico (in Spanish). Librería Editorial "Juventud,".

- ^ Ampuero, Luis P. (1894). Proceso politico contra el ex-presidente de la republica General Hilarion Daza, sus ministros de estado y otros ciudadanos particulares (in Spanish).

- ^ Naranjo, Rodrigo (2011). Para desarmar la narrativa maestra: un ensayo sobre la Guerra del Pacífico (in Spanish). Universidad Católica del Norte. ISBN 978-956-287-324-6.

Bibliography

- Mesa José de; Gisbert, Teresa; and Carlos D. Mesa, "Historia de Bolivia", 3rd edition.

External links

- 1840 births

- 1894 deaths

- Assassinated Bolivian politicians

- Bolivian expatriates in Italy

- Bolivian expatriates in France

- Bolivian generals

- Bolivian military personnel of the War of the Pacific

- Bolivian people of Italian descent

- Defense ministers of Bolivia

- Leaders ousted by a coup

- Leaders who took power by coup

- People from Sucre

- People murdered in Bolivia

- Presidents of Bolivia

- 1894 murders in South America

- Assassinated presidents of Bolivia

- Assassinated presidents in South America

- Politicians assassinated in the 1890s

- National presidents assassinated in the 19th century