Hopisinom | |

|---|---|

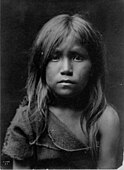

A Hopi girl with a customary Hopi squash blossom hairstyle, woven wearing blanket, jewelry, and an olla. | |

| Total population | |

| 19,338 (2010)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Arizona) | |

| Languages | |

| Hopi, English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Native American Church, Hopi religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pueblo peoples, Uto-Aztecan peoples |

| People | Hopi |

|---|---|

| Language | Hopilàvayi, Hand Talk |

| Country | Hopitutskwa |

The Hopi are Native Americans who primarily live in northeastern Arizona. The majority are enrolled in the Hopi Tribe of Arizona[2] and live on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona; however, some Hopi people are enrolled in the Colorado River Indian Tribes of the Colorado River Indian Reservation[2] at the border of Arizona and California.

The 2010 U.S. census states that about 19,338 US citizens self-identify as being Hopi.[1]

The Hopi language belongs to the Uto-Aztecan language family.

The primary meaning of the word Hopi is "behaving one, one who is mannered, civilized, peaceable, polite, who adheres to the Hopi Way."[3] Some sources contrast this to other warring tribes that subsist on plunder.[4] Hopi is a concept deeply rooted in the culture's religion, spirituality, and its view of morality and ethics. To be Hopi is to strive toward this concept, which involves a state of total reverence for all things, peace with these things, and life in accordance with the instructions of Maasaw, the Creator or Caretaker of Earth. The Hopi observe their religious ceremonies for the benefit of the entire world.

Hopi organize themselves into matrilineal clans. Children are born into the clan of their mother. Clans extend across all villages. Children are named by the women of the father's clan. After the child is introduced to the Sun, the women of the paternal clan gather, and name the child in honor of the father's clan. Children can be given over 40 names.[5] The village members decide the common name. Current practice is to use a non-Hopi or English name or the parent's chosen Hopi name. A person may also change the name upon initiation to traditional religious societies, or a major life event.

The Hopi understand their land to be sacred and understand their role as caretakers of the land that they inherited from their ancestors.[citation needed] Agriculture is significant to their lifeways and economy. Precontact architecture reflects early Hopi society and perceptions of home and family. Many Hopi homes share traits of neighboring Pueblo tribes. Early communal structures, especially Pueblo Great Houses, include living rooms, storage rooms, and religious sanctuaries, called kivas. Each of these rooms allowed for specific activities.[6]

The Hopi encountered Spaniards in the 16th century, and are historically referred to as Pueblo people, because they lived in villages (pueblos in the Spanish language). The Hopi are thought to be descended from the Ancestral Pueblo people (Hopi: Hisatsinom), who constructed large apartment-house complexes and had an advanced culture that spanned the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southwestern Colorado.[7] It is thought that Hopi people descend from those Ancestral Puebloan settlements along the Mogollon Rim of northern Arizona.

Hopi villages are now located atop mesas in northern Arizona. The Hopi originally settled near the foot of the mesas but in the course of the 17th century moved to the mesa tops for protection from the Utes, Apaches, and Spanish.[8]

On December 16, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur passed an executive order creating an Indian reservation for the Hopi. It was smaller than the surrounding land that was annexed by the Navajo Reservation, which is the largest reservation in the country.[9]

As of 2005[10] the Hopi Reservation is entirely surrounded by the much larger Navajo Reservation. As the result of land disputes from 1940 to 1970 or earlier, the two nations used to share the government designated Navajo–Hopi Joint Use Area, but this continued to be a source of conflict. The partition of this area, commonly known as Big Mountain, by Acts of Congress in 1974 and 1996, but as of 2008 has also resulted in long-term controversy.[11][12]

On October 24, 1936, the Hopi Tribe ratified its constitution, creating a unicameral government where all powers are vested in a Tribal Council. The powers of the executive branch (chairman and vice chairman) and judicial branch, are limited. The traditional powers and authority of the Hopi Villages were preserved in the 1936 Constitution.[13]

Oraibi

Old Oraibi is one of four original Hopi villages. It was founded before A.D. 1100 and is one of the oldest continuously inhabited villages within the territory of the United States. In the 1540s the village was recorded as having 1,500– 3,000 residents.[9]

Early European contact, 1540–1680

The first recorded European contact with the Hopi was by the Spanish in 1540. Spanish General Francisco Vásquez de Coronado went to North America to explore the land. While at the Zuni villages, he learned of the Hopi tribe. Coronado dispatched Pedro de Tovar and other members of their party to find the Hopi villages.[14] The Spanish wrote that the first Hopi village they visited was Awatovi. They noted that there were about 16,000 Hopi and Zuni people.[9] A few years later, the Spanish explorer García López de Cárdenas investigated the Rio Grande and met the Hopi. They warmly entertained Cardenas and his men and directed him on his journey.[14]

In 1582–1583 the Hopi were visited by Antonio de Espejo’s expedition. He noted that there were five Hopi villages and around 12,000 Hopi people.[9] During that period the Spanish explored and colonized the southwestern region of the New World, but never sent many forces or settlers to the Hopi country.[14] Their visits to the Hopi were random and spread out over many years. Many times the visits were from military explorations.

The Spanish colonized near the Rio Grande and, because the Hopi did not live near rivers that gave access to the Rio Grande, the Spanish never left any troops on their land.[15] The Spanish were accompanied by missionaries, Catholic friars. Beginning in 1629, with the arrival of 30 friars in Hopi country, the Franciscan Period started. The Franciscans had missionaries assigned and built a church at Awatovi.

Pueblo Revolt of 1680

Spanish Franciscan priests were only marginally successful in converting the Hopi and persecuted them for adhering to Hopi religious practices. The Spanish occupiers enslaved the Hopi populace, forcing them to labor and hand over goods and crops. Spanish oppression and attempts to convert the Hopi caused the Hopi over time to become increasingly intolerant towards their occupiers.[15] The documentary record shows evidence of Spanish abuses. In 1655, a Franciscan priest by the name of Salvador de Guerra beat to death a Hopi man named Juan Cuna. As punishment, Guerra was removed from his post on the Hopi mesas and sent to Mexico City.[16] In 1656, a young Hopi man by the name of Juan Suñi was sent to Santa Fe as an indentured servant because he impersonated the resident priest Alonso de Posada at Awatovi, an act believed to have been carried out in the spirit of Hopi clowning.[17] During the period of Franciscan missionary presence (1629-1680), the only significant conversions took place at the pueblo of Awatovi.[14] In the 1670s, the Rio Grande Pueblo Indians put forward the suggestion to revolt in 1680 and garnered Hopi support.[15]

The Pueblo Revolt was the first time that diverse Pueblo groups had worked in unison to drive out the Spanish colonists. In the Burning of Awatovi, Spanish soldiers, local Catholic Church missionaries, friars, and priests were all put to death, and the churches and mission buildings were dismantled stone by stone. It took two decades for the Spanish to reassert their control over the Rio Grande Pueblos but the Catholic Inquisition never made it back to Hopiland. In 1700, the Spanish friars had begun rebuilding a smaller church at Awatovi. During the winter of 1700–01, teams of men from the other Hopi villages sacked Awatovi at the request of the village chief, killed all the men of the village, and removed the women and children to other Hopi villages, then completely destroyed the village and burned it to the ground. Thereafter, despite intermittent attempts during the 18th century, the Spanish never re-established a presence in Hopi country.[14]

Hopi-U.S. relations, 1849–1946

In 1849, James S. Calhoun was appointed official Indian agent of Indian Affairs for the Southwest Territory of the U.S. He had headquarters in Santa Fe and was responsible for all of the Indian residents of the area. The first formal meeting between the Hopi and the U.S. government occurred in 1850 when seven Hopi leaders made the trip to Santa Fe to meet with Calhoun. They wanted the government to provide protection against the Navajo, a Southern Athabascan-speaking tribe who were distinct from Apaches. At this time, the Hopi leader was Nakwaiyamtewa.

The US established Fort Defiance in 1851 in Arizona, and placed troops in Navajo country to deal with their threats to the Hopi. General James J. Carleton, with the assistance of Kit Carson, was assigned to travel through the area. They "captured" the Navajo natives and forced them to the fort. As a result of the Long Walk of the Navajo, the Hopi enjoyed a short period of peace.[18]

In 1847, Mormons settled in Utah and tried to convert the Indians to Mormonism.[15] Jacob Hamblin, a Mormon missionary, first made a trip into Hopi country in 1858. He was on good terms with the Hopi Indians, and in 1875 an LDS Church was built on Hopi land.[18]

Education

In 1875, the English trader Thomas Keam escorted Hopi leaders to meet President Chester A. Arthur in Washington D.C. Loololma, village chief of Oraibi at the time, was very impressed with Washington.[9] In 1887, a federal boarding school was established at Keams Canyon for Hopi children.[18]

The Oraibi people did not support the school and refused to send their children 35 miles (56 km) from their villages. The Keams Canyon School was organized to teach the Hopi youth the ways of European-American civilization. It forced them to use English and give up their traditional ways.[9] The children were made to abandon their tribal identity and completely take on European-American culture.[19] Children were forced to give up their traditional names, clothing and language. Boys, who were also forced to cut their long hair, were taught European farming and carpentry skills. Girls were taught ironing, sewing, and "civilized" dining. The school also reinforced European-American religions. The American Baptist Home Mission Society made students attend services every morning and religious teachings during the week.[20] In 1890, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Thomas Jefferson Morgan arrived in Hopi country with other government officials to review the progress of the new school. Seeing that few students were enrolled, they returned with federal troops who threatened to arrest the Hopi parents who refused to send their children to school, with Morgan forcibly taking children to fill the school.[9]

Hopi land

Agriculture is an important part of Hopi culture, and their villages are spread out across the northern part of Arizona. The Hopi and the Navajo did not have a conception of land being bounded and divided. The Hopi people had settled in permanent villages, while the nomadic Navajo people moved around the four corners. Both lived on the land that their ancestors did. On December 16, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur issued an executive order creating a reservation for the Hopi. It was smaller than the Navajo Reservation, which was the largest in the country.[9]

The Hopi reservation was originally a rectangle 55 by 70 miles (88.5 by 110 km) in the middle of the Navajo Reservation, with their village lands taking about half of the land.[21] The reservation prevented encroachment by white settlers, but it did not protect the Hopis against the Navajos.[9]

The Hopi and the Navajo fought over land, and they had different models of sustainability, as the Navajo were sheepherders. Eventually the Hopi went before the Senate Committee of Interior and Insular Affairs to ask them to help provide a solution to the dispute. The tribes argued over approximately 1,800,000 acres (7,300 km2) of land in northern Arizona.[22] In 1887 the U.S. government passed the Dawes Allotment Act. The purpose was to divide up communal tribal land into individual allotments by household, to encourage a model of European-American style subsistence farming on individually owned family plots of 640 acres (2.6 km2) or less. The Department of Interior would declare remaining land "surplus" to the tribe's needs and make it available for purchase by U.S. citizens. For the Hopi, the Act would destroy their ability to farm, their main means of income[citation needed]. The Bureau of Indian Affairs did not set up land allotments in the Southwest.[23]

Oraibi split

The chief of the Oraibi, Lololoma, enthusiastically supported Hopi education, but his people were divided on this issue.[24] Most of the village was conservative and refused to allow their children to attend school. These natives were referred to as "hostiles" because they opposed the American government and its attempts to force assimilation. The rest of the Oraibi were called "friendlies" because of their acceptance of white people and culture. The "hostiles" refused to let their children attend school. In 1893, the Oraibi Day School was opened in the Oraibi village. Although the school was in the village, traditional parents still refused to allow their children to attend. Frustrated with this, the US Government often resorted to intimidation and force in the form of imprisonment as a means of punishment.

In November 1894, Captain Frank Robinson and a group of soldiers were dispatched to enter the village and arrested 18 of the Hopi resisters. Among those arrested were Habema (Heevi'ima) and Lomahongyoma. In the following days, they realized they had not captured all Hopi resisters and Sergeant Henry Henser was sent back to capture Potopa, a Hopi medicine man, known as "one of the most dangerous of resisters".[25] Eager to rid Orayvi of all resisters, government officials sent 19 Hopi men who they saw as troublesome to Alcatraz Prison, where they stayed for a year.[9] The US Government thought they undermined the Hopi resistance, however this only intensified ill feelings of bitterness and resistance towards the government. When the Hopi prisoners were sent home, they claimed that government officials told them that they did not have to send their children to school, but when they returned, Indian agents denied that this was promised to them.[25] Another Oraibi leader, Lomahongyoma, competed with Lololoma for village leadership. In 1906 the village split after a conflict between hostiles and friendlies. The conservative hostiles left and formed a new village, known as Hotevilla.[18]

Federal recognition

At the dawn of the 20th century, the U.S. government established day schools, missions, farming bureaus, and clinics on every Indian reservation. This policy required that every reservation set up its own police force and tribal courts and appointed a leader who would represent their tribe to the U.S. government. In 1910 in the Census for Indians, the Hopi Tribe had a total of 2,000 members, which was the highest in 20 years. The Navajo at this time had 22,500 members and have consistently increased in population. During the early years of this century, only about three percent of Hopis lived off the reservation.[21] In 1924 Congress officially declared Native Americans to be U.S. citizens with the Indian Citizenship Act.

Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the Hopi established a constitution to create their own tribal government, and in 1936 elected a Tribal Council.[18] The Preamble to the Hopi constitution states that they are a self-governing tribe, focused on working together for peace and agreements between villages in order to preserve the "good things of Hopi life." The constitution consists of 13 articles, addressing territory, membership, and organization of their government with legislative, executive and judicial branches.[26]

Hopi–Navajo land disputes

From the 1940s to the 1970s, the Navajo moved their settlements closer to Hopi land, causing the Hopi to raise the issue with the U.S. government. This resulted in the establishment of "District 6" which placed a boundary around the Hopi villages on the first, second, and third mesas, thinning the reservation to 501,501 acres (2,029.50 km2).[18] In 1962 the courts issued the "Opinion, Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law and Judgment," which stated that the U.S. government did not grant the Navajo any type of permission to reside on the Hopi Reservation that was declared in 1882; and that the remaining Hopi land was to be shared with the Navajo, as the Navajo–Hopi Joint Use Area.[27]

From 1961 to 1964, the Hopi tribal council signed leases with the U.S. government that allowed companies to explore and drill for oil, gas, and minerals in Hopi country. This drilling brought over three million dollars to the Hopi Tribe.[28] In 1974, The Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement Act was passed,(Public Law 93–531; 25 U.S.C. 640d et seq.), followed by the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute Settlement Act of 1996, settling some issues not resolved in 1974.[29] The 1974 Act created the Office of Navajo and Hopi Indian Relocation, which forced the relocation of any Hopi or Navajo living on the other's land. In 1992, the Hopi Reservation was increased to 1,500,000 acres (6,100 km2).[27]

Today's[when?] Hopi Reservation is traversed by Arizona State Route 264, a paved road that links the numerous Hopi villages.

Tribal government

On October 24, 1936, the Hopi Tribe of Arizona ratified a constitution. That constitution created a unicameral government where all powers are vested in a Tribal Council. While there is an executive branch (tribal chairman and vice chairman) and judicial branch, their powers are limited under the Hopi Constitution. The traditional powers and authority of the Hopi villages was preserved in the 1936 constitution.[13]

The Hopi tribe is federally recognized and headquartered in Kykotsmovi, Arizona.

Tribal officers

The current tribal officers are:[30]

- Chairman: Timothy Nuvangyaoma

- Vice Chairman: Clark W. Tenakhongva

- Tribal Secretary: Theresa Lomakema

- Treasurer: Wilfred Gaseoma

- Sergeant-at-Arms: Alfonso Sakeva

Tribal council

Representatives to the council are selected either by a community election or by an appointment from the village kikmongwi, or leader. Each representative serves a two-year term. Representation on the Tribal Council as of December 2017 is as follows:[30]

Village of Upper Moenkopi: Hubert Lewis Sr., Michael Elmer, Robert Charley, Philton Talahytewa Sr.

Village of Bacavi: Dwayne Secakuku, Clifford Quotsaquahu

Village of Kykotsmovi: David Talayumptewa, Phillip Quochytewa Sr., Danny Honanie, Herman G. Honanie

Village of Sipaulavi: Rosa Honanie,

Village of Mishongnovi: Emma Anderson, Craig Andrews, Pansy K. Edmo, Rolanda Yoyletsdewa

First Mesa Consolidated Villages: Albert T. Sinquah, Ivan Sidney Sr., Wallace Youvella Jr., Dale Sinquah

Currently, the villages of Shungopavi, Oraibi, Hotevilla, and Lower Moenkopi do not have a representative on council.[30] The Hopi Villages select council representatives, and may decline to send any representative. The declination has been approved by the Hopi Courts.[31]

Tribal courts

The Hopi Tribal Government operates a Trial Court and Appellate Court in Keams Canyon. These courts operate under a Tribal Code, amended August 28, 2012.[32]

Economic development

The Hopi tribe earns most of its income from natural resources. The tribe's 2010 operating budget was $21.8 million, and projected mining revenues for 2010 were $12.8 million.[33] On the 1,800,000-acre (7,300 km2) Navajo Reservation, a significant amount of coal is mined yearly from which the Hopi Tribe shares mineral royalty income.[23] Peabody Western Coal Company is one of the largest coal operations on Hopi land, with long-time permits for continued mining.[34] Consequently, the closure of a large coal mine in 2019 has compounded existing unemployment. Combined with the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of official help for those who have lost access to the coal they need to burn to heat their homes, Hopi have turned to nonprofits for help.[35]

The Hopi Tribe Economic Development Corporation (HTEDC) is the tribal enterprise charged with creating diverse, viable economic opportunities.[36] The HEDC oversees the Hopi Cultural Center and Walpi Housing Management. Other HTEDC businesses include the Hopi Three Canyon Ranches, between Flagstaff and Winslow and the 26 Bar Ranch in Eagar; Hopi Travel Plaza in Holbrook; three commercial properties in Flagstaff; and the Days Inn Kokopelli in Sedona.[37]

Tourism is a source of income. The Moenkopi Developers Corporation, a non-profit entity owned by the Upper village of Moenkopi, opened the 100-room Moenkopi Legacy Inn and Suites in Moenkopi, Arizona, near Tuba City, Arizona.[38] It is the second hotel on the reservation. It provides non-Hopi a venue for entertainment, lectures, and educational demonstrations, as well as tours and lodging. The project is expected to support 400 jobs.[39] The village also operates the Tuvvi Travel Center in Moenkopi.[40] The Tribally owned and operated Hopi Cultural Center on Second Mesa includes gift shops, museums, a hotel, and a restaurant that serves Hopi dishes.[41]

The Hopi people have repeatedly voted against gambling casinos as an economic opportunity.[42]

On November 30, 2017, in his last day as Chairman of the Hopi Tribe, Herman G. Honanie and Governor Doug Ducey signed the Hopi Tribe-State of Arizona Tribal Gaming Compact, a year after the Tribe approved entering into a compact with the State of Arizona. The historic agreement, which gives the Hopi Tribe the opportunity to operate or lease up to 900 Class III gaming machines, makes Hopi the 22nd and last Arizona tribe to sign a gaming compact with the State.[43]

Culture

The Hopi Dictionary gives the primary meaning of the word "Hopi" as: "behaving one, one who is mannered, civilized, peaceable, polite, who adheres to the Hopi Way".[3] Some sources contrast this to other warring tribes that subsist on plunder,[4] considering their autonym, Hopisinom to mean "The Peaceful People" or "Peaceful Little Ones".[44] However, Malotki maintains that "neither the notion 'peaceful' nor the idea 'little' are semantic ingredients of the term".[45]

According to Barry Pritzker, "...many Hopi feel an intimate and immediate connection with their past. Indeed, for many Hopi, time does not proceed in a straight line, as most people understand it. Rather, the past may be past and present more or less simultaneously.". In the present Fourth World, the Hopi worship Masauwu, who admonished them to "always remember their gods and to live in the correct way". The village leader, kikmongwi, "promoted civic virtue and proper behavior".[46]

Traditionally, Hopi are organized into matrilineal clans. When a man marries, the children from the relationship are members of his wife's clan. These clan organizations extend across all villages. Children are named by the women of the father's clan. On the 20th day of a baby's life, the women of the paternal clan gather, each woman bringing a name and a gift for the child. In some cases where many relatives would attend, a child could be given over 40 names, for example. The child's parents generally decide the name to be used from these names. Current practice is to either use a non-Hopi or English name or the parent's chosen Hopi name. A person may also change the name upon initiation into one of the religious societies, such as the kachina society, or with a major life event.[citation needed]

The Hopi practice a complete cycle of traditional ceremonies although not all villages retain or had the complete ceremonial cycle. These ceremonies take place according to the lunar calendar and are observed in each of the Hopi villages. Like other Native American groups, the Hopi have been influenced by Christianity and the missionary work of several Christian denominations. Few have converted enough to Christianity to drop their traditional religious practices.[citation needed]

The most widely publicized of Hopi katsina rites is the "Snake Dance", an annual event during which the performers danced while handling live snakes.[47]

Traditionally the Hopi are micro or subsistence farmers. The Hopi also are part of the wider cash economy; a significant number of Hopi have mainstream jobs; others earn a living by creating Hopi art, notably the carving of katsina dolls, the crafting of earthenware ceramics, and the design and production of fine jewelry, especially sterling silver.

The Hopi collect and dry a native perennial plant called Thelesperma megapotamicum, known by the common name Hopi tea, and use it to make an herbal tea, as a medicinal remedy and a yellow dye.[48]

Albinism

The Hopi have a high rate of albinism. Primarily in Second Mesa and west villages towards Hotevilla—about 1 in 200 individuals.[49]

Notable Hopi people

- Thomas Banyacya (ca. 1909–1999), interpreter and spokesman for traditional Hopi leaders

- Neil David Sr. (born 1944), painter, illustrator, and katsina figure carver

- Dan Evehema (born circa 1893–1999), traditional Hopi leader and author

- Jean Fredericks (1906–1990), Hopi photographer and former Tribal Council chairman[50][51]

- Iva Honyestewa, basket maker, food activist, educator

- Diane Humetewa (born 1964), Appointed by President Obama to be a U.S. District Court Judge

- Fred Kabotie (circa 1900–1986), painter and silversmith

- Michael Kabotie (1942–2009), painter, sculptor, and silversmith

- Jacob Koopee Jr. (Hopi-Tewa, 1970 – 2011), American Hopi/Tewa potter and artist

- Charles Loloma (1912–1991), jeweler, ceramic artist, and educator

- Linda Lomahaftewa, (Hopi/Choctaw, born 1947) printmaker, painter, and educator

- David Monongye (birth date unknown), Hopi traditional leader; Son of Yukiuma, keeper of the Fire Clan Tablets

- Helen Naha (1922–1993) potter

- Tyra Naha, potter

- Dan Namingha (Hopi-Tewa, born 1950), painter and sculptor

- Elva Nampeyo (Hopi-Tewa), potter

- Fannie Nampeyo (Hopi-Tewa), potter

- Iris Nampeyo (Nampeyo, (Hopi-Tewa), circa 1860–1942), potter

- Lori Piestewa (1979–2003), US Army Quartermaster Corps soldier killed in Iraq War

- Dextra Quotskuyva (1928–2019), potter

- Emory Sekaquaptewa (1928–2007), Hopi leader, linguist, lexicon maker, commissioned officer of US Army (West Point graduate), jeweler, silversmith

- Phillip Sekaquaptewa (born 1956), jeweler, silversmith (nephew of Emory)

- Don C. Talayesva (ca. 1891–1985), autobiographer and traditionalist

- Lewis Tewanima (1888–1969), Olympic distance runner and silver medalist

- Tuvi (Chief Tuba) (circa 1810–1887), first Hopi convert to Mormonism after whom Tuba City, Arizona, was named

Gallery

-

Hopi Women's Dance, 1879, Oraibi, Arizona, photo by John K. HillersStreet

-

Hopi Basket Weaver

-

Hopi Basket Weaver c. 1900, photo by Henry Peabody

-

Iris Nampeyo, world-famous Hopi ceramist, with her work, c. 1900, photo by Henry Peabody

-

Hopi girl at Walpi, c. 1900, with squash blossom hairstyle indicative of her eligibility for courtship, the squash flower being a symbol of fertility.[52]

-

Hopi Indian man weaving a blanket by C. C. Pierce, ca.1900

-

Hopi woman dressing hair of unmarried girl, c. 1900, photo by Henry Peabody

-

Hopi girl, photo by Edward S. Curtis (circa 1905)

-

Traditional Hopi homes, c. 1906, photo by Edward S. Curtis

-

Four young Hopi women grinding grain, c. 1906, photo by Edward S. Curtis

-

Hopi girl, 1922, photo by Edward S. Curtis

-

Hopi woman, 1922, photo by Edward S. Curtis

-

Hopi girls, 1922, photo by Edward S. Curtis

-

Traditional Hopi village of Walpi, 1941, photo by Ansel Adams

-

Children with chopper bicycle, Hopi Reservation, 1970

-

Hopi dancers in 2017

See also

References

- ^ a b Bureau, U. S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)[permanent dead link] - ^ a b Newland, Bryan (January 2, 2023). "Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Federal Register (88 FR 2112): 2112–16.

- ^ a b The Hopi Dictionary Project, Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology (1998), Hopi Dictionary / Hopìikwa Lavàytutuveni: A Hopi-English Dictionary of the Third Mesa Dialect, Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 99–100, ISBN 0-8165-1789-4

- ^ a b Connelly, John C., "Hopi Social Organization." In Alfonso Ortiz, vol. ed., Southwest, vol. 9, in William C. Sturtevant, ed., Handbook of North American Indians, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1979: 539–53, p. 551

- ^ "Hopi-Tewa | Land Acknowledgment Toolkit". NMAHC. Retrieved 2024-04-19.

- ^ Adams, E. Charles (January 1983). "The Architectural Analogue to Hopi Social Organization and Room Use, and Implications for Prehistoric Northern Southwestern Culture". American Antiquity. 48 (1): 44–61. doi:10.2307/279817. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 279817. S2CID 161329464.

- ^ "Ancestral Pueblo culture." Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Fewkes, Jesse Walter (1900), Tusayan Migration Traditions, 19th Annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 580–1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Whiteley, Peter M. Deliberate Acts, Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press, 1988: 14–86.

- ^ "Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement".

- ^ "NAVAJO - HOPI Land Dispute, history, maps, links". www.kstrom.net. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ "The Navajo-Hopi Land Issue: A Chronology". Archived from the original on 2008-05-30.

- ^ a b Justin B. Richland, Arguing With Tradition, (University of Chicago Press, 2004) 35.

- ^ a b c d e Brew, J.O. "Hopi Prehistory and History to 1850." In Alonso Ortiz, vol. ed., Southwest, vol. 9, in William C. Sturtevant, gnl. ed., Handbook of North American Indians, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1979: 514–523.

- ^ a b c d Clemmer, Richard O. Roads in the Sky, Boulder, Colorado.: Westview Press, Inc., 1995: 30–90.

- ^ Scholes, France V. Troublous Times in New Mexico, 1659-1670. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1942. 1942

- ^ Daughters, Anton. "A Seventeenth-Century Instance of Hopi Clowning?" Kiva 74:4 (Summer 2009) 2009

- ^ a b c d e f Dockstader, Frederick J. "Hopi History, 1850–1940." In Alonso Ortiz, vol. ed., Southwest, vol. 9, in William C. Sturtevant, gnl. ed., Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1979: 524–532.

- ^ Pecina, Ron and Pecina, Bob. Neil David's Hopi World. Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2011. ISBN 978-0-7643-3808-3

- ^ Adams, David Wallace. "Schooling the Hopi: Federal Indian Policy Writ Small, 1887–1917", The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 48, No. 3. University of California Press, (1979): 335–356.

- ^ a b Johansson, S. Ryan., and Preston, S.H. "Tribal Demography: The Hopi and Navaho Populations as Seen through Manuscripts from the 1900 U.S. Census", Social Science History, Vol. 3, No. 1. Duke University Press, (1978): 1–33.

- ^ United States Congress, Senate, Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute: Hearing before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, 1974, Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, (1974): 1–3.

- ^ a b Hopi Education Endowment Fund Archived 2009-10-11 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed: November 13, 2009.

- ^ Talayesva, Don. C. (1970). Sun Chief: The Autobiography of a Hopi Indian (2nd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-300-19103-5.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Matthew (2010). Education beyond the Mesas. University of Nebraska. ISBN 9780803216266.

- ^ "Constitution of the Hopi Tribe" Archived 2021-04-14 at the Wayback Machine, National Tribal Justice Resource Center's Tribal Codes and Constitutions. November 28, 2009.

- ^ a b "Navajo-Hopi Joint Use Area". Hopi Cultural Preservation Office. November 12, 2009. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ Clemmer, Richard O. (1979). "Hopi History, 1940–1974". In Ortiz, Alfonso; Sturtevant, William C. (eds.). Southwest. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 9. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 533–538. OCLC 26140053.

- ^ "Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute Settlement Act of 1996, PUBLIC LAW 104–301" (PDF). October 11, 1996. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Tribal Government". The Hopi Tribe.

- ^ In The Matter of Village Authority To Remove Tribal Council Representatives, Hopi Appellate Court, Appellate Court Case No. 2008-AP 0001

- ^ "Hopi Code" (PDF). The Hopi Tribe. 28 August 2012.

- ^ Berry, Carol (13 January 2010). "Hopi Tribal Council's new structure irks some critics". Indiancountrytoday.com.

- ^ Berry, Carol (14 January 2009). "Coal permit expansion approved as Hopi chairman resigns". Indiancountrytoday.com.

- ^ Sevigny, Melissa (16 January 2023). "Grassroots efforts bring firewood to Hopi people". NPR. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ Hopi Tribe Economic Development Corporation

- ^ May, Tina (6 January 2010). "Hopi Economic Development Corp. Transition Team Off to a Fast Start". Hopi-nsn.gov. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ "New Hopi Hotel near Tuba City is Now Open!". Experiencehopi.com. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Fonseca, Felicia (9 December 2009). "Hopi hotel showcases Arizona tribe's culture". Indiancountrytoday.com.

- ^ "Tuvvi Travel Center". Experiencehopi.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ "Hopi Cultural Center". Hopi Cultural Center. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ Helms, Kathy (20 May 2004). "Hopi again vote down gambling". Gallup Independent. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ "Hopi tribe last in the state to sign gaming compact". azcentral. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ Smith, L. Michael (2000). "Hopi: The Real Thing". Ausbcomp.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-01.

- ^ Malotki, Ekkehart (1991), "Language as a key to cultural understanding: New interpretations of Central Hopi concepts", Baessler-Archiv, 39: 43–75

- ^ Pritzker, Barry (2011). The Hopi. New York: Chelsea House. pp. 16–17, 25. ISBN 9781604137989.

- ^ "Hopi people". Encyclopedia Britannica. 28 March 2008.

- ^ "Medicinal Plants of the Southwest Thelesperma megapotamicum". New Mexico State University. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Hedrick, Philip (June 2003). "Hopi Indians, "cultural" selection, and albinism". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (2): 151–156. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10180. PMID 12740958.

- ^ Masayesva, Victor. Hopi Photographers, Hopi Images. Tucson, AZ: Sun Tracks & University of Arizona Press, 1983: 42. ISBN 978-0-8165-0809-9.

- ^ Hoxie, Frederick. Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996: 480. ISBN 978-0-395-66921-1

- ^ Nanda, Serena; Warms, Richard L (April 4, 2023). "11, Matrilineal Families". Cultural Anthropology. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781071858271. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- Adams, David Wallace. "Schooling the Hopi: Federal Indian Policy Writ Small, 1887–1917." The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 48, No. 3. University of California Press, (1979): 335–356.

- Brew, J.O. "Hopi Prehistory and History to 1850." In Alonso Ortiz, vol. ed., Southwest, vol. 9, in William C. Sturtevant, gnl. ed., Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1979: 514–523.

- Clemmer, Richard O. "Hopi History, 1940–1974." In Alonso Ortiz, vol. ed., Southwest, vol. 9, in William C. Sturtevant, gnl. ed., Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1979: 533–538.

- Clemmer, Richard O. "Roads in the Sky." Boulder, Colorado.: Westview Press, Inc., 1995: 30–90.

- "Constitution of the Hopi Tribe. National Tribal Justice Resource Center's Tribal Codes and Constitutions". Tribalresourcecenter.org. November 13, 2009. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- Dockstader, Frederick J. "Hopi History, 1850–1940." In Alonso Ortiz, vol. ed., Southwest, vol. 9, in William C. Sturtevant, gnl. ed., Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1979: 524–532.

- "Hopi Cultural Preservation Office". Northern Arizona University. November 12, 2009. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- "Partners". Hopi Education Endowment Fund. November 13, 2009. Archived from the original on October 11, 2009.

- Johansson, S. Ryan., and Preston, S.H. "Tribal Demography: The Hopi and Navaho Populations as Seen through Manuscripts from the 1900 U.S. Census." Social Science History, Vol. 3, No. 1. Duke University Press, (1978): 1–33.

- Pecina, Ron and Pecina, Bob. Neil David's Hopi World. Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2011. ISBN 978-0-7643-3808-3. 86-89

- U.S. Department of State, Navajo–Hopi Land Dispute: Hearing before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, 1974. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, (1974): 1–3.

- Whiteley, Peter M. "Deliberate Acts." Tucson, Arizona: The University of Arizona Press, 1988.: 14–86.

Further reading

- Clemmer, Richard O. "Roads in the Sky: The Hopi Indians In A Century of Change". Boulder: Westview Press, 1995.

- Harold Courlander, "Fourth World of the Hopi" University of New Mexico Press, 1987

- "Voice of Indigenous People – Native People Address the United Nations" Edited by Alexander Ewen, Clear Light Publishers, Santa Fe NM, 1994, 176 pages. Thomas Banyacya et al. at the United Nations

- Glenn, Edna; Wunder, John R.; Rollings, Willard Hughes; et al., eds. (2008). Hopi Nation: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law (Ebook ed.). digitalcommons.unl.edu.

- Harry James, Pages from Hopi History University of Arizona Press, 1974

- Laird, W. David (1977). Hopi Bibliography: Comprehensive and Annotated. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0816506337.

- Susanne and Jake Page, Hopi, Abradale Press, Harry N. Abrams, 1994, illustrated oversize hardcover, 230 pages, ISBN 0-8109-8127-0, 1982 edition, ISBN 0-8109-1082-9

- Secakuku, Alph H. (1995). Hopi Kachina Tradition: Following the Sun and Moon. Flagstaff: Northland Publishing. ISBN 978-0873586443.

- Alfonso Ortiz, ed. Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 9, Southwest. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1979. ISBN 0-16-004577-0.

- New York Times article, "Reggae Rhythms Speak to an Insular Tribe" by Bruce Weber, September 19, 1999

- Pecina, Ron and Pecina, Bob. Neil David's Hopi World. Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2011. ISBN 978-0-7643-3808-3

- Frank Waters, The Book of the Hopi. Penguin (Non-Classics), (June 30, 1977), ISBN 0-14-004527-9

- Frank Waters, Masked Gods:Navaho & Pueblo Ceremonialism, Swallow Press, 1950; Ohio University Press, 1984, ISBN 0-8040-0641-5

- James F. Brooks, Mesa of Sorrows: A History of the Awat'ovi Massacre, W.W. Norton & Company, 2016; ISBN 9780393061253

External links

- Official website

- A Summary of Hopi Native American History Archived 2021-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Four Corners Postcard: General information on Hopi Archived 2019-05-01 at the Wayback Machine, by LM Smith

- The Unwritten Literature of the Hopi, by Hattie Greene Lockett at Project Gutenberg

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Hopi Indians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Hopi Indians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Frank Waters Foundation Archived 2019-03-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Sikyatki (ancestral Hopi) pottery

- Hopi Cultural Preservation Office

- Hopi movie "Techqua Ikachi" part 1 and Hopi movie "Techqua Ikachi" part 2 on YouTube

![Hopi girl at Walpi, c. 1900, with squash blossom hairstyle indicative of her eligibility for courtship, the squash flower being a symbol of fertility.[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cd/Hopi_walpi.jpg/136px-Hopi_walpi.jpg)

![Hopi Indian man weaving a blanket by C. C. Pierce [de], ca.1900](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Hopi_Indian_man_weaving_a_blanket%2C_ca.1900_%28CHS-3931%29.jpg/160px-Hopi_Indian_man_weaving_a_blanket%2C_ca.1900_%28CHS-3931%29.jpg)