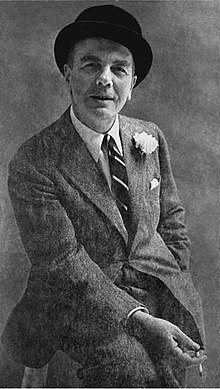

Iles Brody | |

|---|---|

Brody c. 1953 | |

| Born | Illés Bródy December 27, 1899 |

| Died | November 11, 1953 (aged 53) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Other names | Elias Brody |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Notable work | Gone with the Windsors |

| Spouse(s) | Vera Robertson (1927–1932; divorced) Marie Hollingsworth (1938–??; likely divorced) Sanna Klaveness (1949–1953; his death) |

| Relatives | Sándor Bródy (father) |

Illés Bródy ([ˈileːʃ] EE-laysh, December 27, 1899 – November 11, 1953)[1][a] was a Hungarian-born journalist and writer who lived in the United States from the 1930s.[5] After a false start as a portrait artist, he became known as a food writer and gourmet. For his writing career his preferred spelling of his own name was Iles Brody; other sources sometimes anglicized his name as Elias Brody.

Early life

Brody was born in Budapest, Hungary, the youngest son of writers Sándor Bródy and Isabella Rosenfeld.[5][8] His family was Jewish.[10] After serving in the Hungarian cavalry in his youth,[11] he travelled extensively throughout Europe.[5]

In 1927, he married American Follies dancer Vera "Kittens" Leightmer (née Robertson, 1899–1997).[12][13][14] The couple had met in Paris, married in Budapest,[3] and settled in New York City, but the marriage proved tumultuous and ended in divorce in 1932:[15] Brody (then described as a portrait artist) had reportedly bashed Leightmer prior to their engagement, and attempted suicide several times during the course of their relationship.[16][17][18] The couple was also involved in a highly publicized court case when Leightmer unsuccessfully sued a prominent American banker, Jefferson Seligman, for breach of promise.[19]

In 1932, after separating from Leightmer, Brody was convicted in London, England of blackmailing two American sisters, Mildred Reid Burke and Constance Reid Netcher. Although he maintained his innocence, he was jailed for ten months and was deported from England after serving his sentence.[20][21][22]

In 1938, after returning to the U.S., he married Marie Hollingsworth in Virginia.[23] This marriage appears to have also ended in divorce prior to 1949.

Later writing career

In the late 1930s, Brody returned to New York City, where he became a regular columnist for Esquire magazine. As a former cavalry officer, his early contributions were on equestrian sports and horsemanship. He later became a food writer, with a long-running column called "Man the Kitchenette", which – somewhat unusually for the era – offered culinary advice intended for a male readership.[5][24] He also wrote for Gourmet magazine.[25]

Brody published two books relating to gastronomy: On the Tip of My Tongue (1944)[26] and The Colony: Portrait of a Restaurant and its Famous Recipes (1945), a history of the noted New York restaurant.[27]

His third and final book, for which he is probably best remembered, was Gone with the Windsors (1953), a best-selling[1] exposé of Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. American critic E.V. Durling described it as "the most brilliantly written book so far dealing with the lives and loves of the Duke and Duchess."[28] Other reactions were less favorable: the British tabloid The People denounced the work as "scurrilous", called attention to Brody's 1932 blackmail conviction, and discouraged Brody's prospective British publishers from publishing the book in Britain.[22] Brody had struggled for three years to find a U.S. publisher for Gone with the Windsors,[29] and was reportedly pressured by associates of the Duke and Duchess not to publish the book.[30] The Duchess of Windsor is reported to have expressed relief when Brody died shortly after its publication.[31][11]

Death

Brody died suddenly of a heart attack on November 11, 1953, while staying at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco.[29][7] He was survived by his third wife, Sanna Klaveness,[32][33] whom he had married in 1949.[34]

Bibliography

- On the Tip of My Tongue (1944)

- The Colony (1945)

- Gone with the Windsors (1953)

Notes

References

- ^ a b "Iles Brody, 54, Wrote 'Gone With the Windsors'". The New York Times. November 12, 1953. p. 31. (subscription required)

- ^ "Hungary Civil Registration, 1895-1980: Births, 1899". FamilySearch. Retrieved 25 November 2019. (registration required)

- ^ a b "Hungary Civil Registration, 1895-1980: Marriages, 1927". FamilySearch. Retrieved 23 November 2019. (registration required)

- ^ "New York, Southern District, U.S District Court Naturalization Records, 1824-1946". Family Search. Retrieved 23 November 2019. (registration required)

- ^ a b c d e Fakazis, Elizabeth (2011). "Esquire Mans the Kitchenette". Gastronomica. 11 (3): 29–39. doi:10.1525/gfc.2011.11.3.29. ISSN 1529-3262. JSTOR 10.1525/gfc.2011.11.3.29. (registration required)

- ^ "California Death Index, 1940-1997". FamilySearch. Retrieved 23 November 2019. (registration required)

- ^ a b "California, San Francisco County Records, 1824-1997". FamilySearch.org. Retrieved 23 November 2019. (registration required)

- ^ a b Brody, Alexander (May 2004). "Akit az Isten jókedvében teremtett". Ketezer.hu (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on August 9, 2016.

- ^ "Windsors' Critic Succumbs at 54". Spokane Chronicle. November 12, 1953. p. 14.

- ^ Singer, Isidore; Weisz, Max (1906). "Bródy, Sándor". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ a b Morton, Andrew (2018). Wallis in Love: The Untold True Passion of the Duchess of Windsor. Michael O'Mara Books. ISBN 978-1-78243-723-9.

- ^ "Kittens' Birthday a Double Riddle". The Sunday News. New York. September 22, 1929. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Obituaries: Vera L. Cuyler". Tampa Bay Times. April 11, 1997. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Social Register's 'Very Grave Social Error'". The Salt Lake Tribune. December 29, 1940 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Follies Girl gets Divorce from Artist". Chicago Tribune. June 8, 1932. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Beats Up Follies Girl, Shoots Self, Then Marries Her". The St. Louis Star. May 4, 1928. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fierce Love Leads To Suicide Attempt". Brooklyn Daily Times. December 18, 1929. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "But They 'Love Her and Leave Her'". The San Francisco Examiner. February 14, 1932. p. 83 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Kittens' Neighbors Turn Catty". Daily News. New York. November 8, 1929. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "He Gave Them Black Eyes O.K.; He Gave Them Blackmail K.O." Minneapolis Sunday Tribune. June 19, 1932. p. 48 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Iles Brody Gets 10 Months Term in London". Daily News. New York. April 14, 1932. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Here's the Kind of Worm He Is". The People. London. September 27, 1953 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required)

- ^ "Virginia, Marriage Certificates, 1936-1988". FamilySearch.org. Retrieved 23 November 2019. (registration required)

- ^ Breazeale, Kenon (2000). "In Spite of Women: Esquire Magazine and the Construction of the Male Consumer". In Scanlon, Jennifer (ed.). The Gender and Consumer Culture Reader. NYU Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-8147-8132-6.

- ^ Reichl, Ruth, ed. (2006). History in a Glass: Sixty Years of Wine Writing from Gourmet. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 9780679643128.

- ^ "Good Taste". The West Australian. Perth. April 5, 1947. p. 5 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ DeCasseres, Benjamin (October 14, 1945). "The World of Books". Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph. p. 59 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Durling, E.V. (September 11, 1953). "On The Side". The Salt Lake Tribune. p. 8A – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Barkham, John (December 6, 1953). "Among Books, Authors". Tampa Bay Times. p. 4G.

- ^ Sifakis, Carl (2005). The Mafia Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Facts on File Inc. p. 269. ISBN 0816056943.

- ^ Maxwell, Elsa (December 18, 1955). "What the Duchess of Winsdor Won't Tell in her Memoirs". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. pp. 7, 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Deaths: Brody, Iles". The New York Times. November 16, 1953. p. 25.

- ^ "Deaths: LURIE, Sanna Klaveness". The New York Times. June 5, 2005.

- ^ Winchell, Walter (December 15, 1948). "On Broadway". Chillicothe Gazette. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.