Pregnancy rate is the success rate for getting pregnant. It is the percentage of all attempts that leads to pregnancy, with attempts generally referring to menstrual cycles where insemination or any artificial equivalent is used, which may be simple artificial insemination (AI) or AI with additional in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Definitions

There is no universally accepted definition of the term. Thus in IVF pregnancy rates may be based on initiated treatment cycles, cycles that underwent oocyte retrieval, or cycles where an embryo transfer was performed. In terms of outcome, "pregnancy" may refer to a positive pregnancy test, evidence of a pregnancy with a "viable" fetus or implantation. Furthermore, pregnancy rates can be influenced in IVF by transferring multiple embryos that may result in multiple births. A strict definition in the IVF setting would refer to the singleton pregnancy rate that determines how many live singletons are born in relation to initiated IVF cycles.

Related end-points

In some cases, success rates include delivery or presence of a live baby (preferably specified as delivery rate or live birth rate respectively).

Fertilization rate

In IVF or its derivatives, fertilization rate may be used to measure how many oocytes become fertilized by sperm cells. A fertilization rate of zero in one cycle, where no oocytes become fertilized, is termed a total fertilization failure.[1] Repeated ICSI treatment may be useful or necessary in couples with total fertilization failure.[1]

Implantation rate

Implantation rate is the percentage of embryos which successfully undergo implantation compared to the number of embryos transferred in a given period. In practice, it is generally calculated as the number of intrauterine gestational sacs observed by transvaginal ultrasonography divided by the number of transferred embryos.[2] As an example, one center in the United States reported an implantation rate in IVF of 37% at a maternal age of less than 35 years, 30% at 35 to 37 years, 22% at 38 to 40 years, and 12% at 41 to 42 years.[3]

Successful implantation of the zygote into the uterus is most likely 8 to 10 days after conception. If the zygote has not implanted by day 10, implantation becomes increasingly unlikely in subsequent days.[4]

Live birth rate

Live birth rate is the percentage of all cycles that lead to live birth, and is the pregnancy rate adjusted for miscarriages and stillbirths. For instance, in 2007, Canadian clinics reported a live birth rate of 27% with in vitro fertilisation.[5]

General factors

There is a substantial connection between age and female fertility. Menarche, the first menstrual period, usually occurs around 12–13, although it may happen earlier or later, depending on each girl. After puberty, female fertility increases and then decreases, with advanced maternal age causing an increased risk of female infertility.

A 2001 review suggested a paternal age effect on fertility, where older men have decreased pregnancy rates.[7]

Pregnancy rate for sexual intercourse

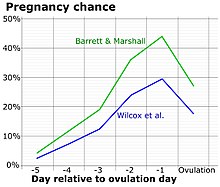

The time with the highest likelihood of pregnancy resulting from sexual intercourse covers the menstrual cycle time from some 5 days before until 1 to 2 days after ovulation.[10] In a 28‑day cycle with a 14‑day luteal phase, this corresponds to the second and the beginning of the third week. A variety of methods have been developed to help individual women estimate the relatively fertile and the relatively infertile days in the cycle; these systems are called fertility awareness.

There are many fertility testing methods, including urine test kits that detect the LH surge that occurs 24 to 36 hours before ovulation; these are known as ovulation predictor kits (OPKs).[11] Computerized devices that interpret basal body temperatures, urinary test results, or changes in saliva are called fertility monitors. Fertility awareness methods that rely on cycle length records alone are called calendar-based methods.[12] Methods that require observation of one or more of the three primary fertility signs (basal body temperature, cervical mucus, and cervical position)[13] are known as symptoms-based methods.[12]

For optimal pregnancy chance, there are recommendations of sexual intercourse every 1 or 2 days,[14] or every 2 or 3 days.[15] Studies have shown no significant difference between different sex positions and pregnancy rate, as long as it results in ejaculation into the vagina.[16] According to the American Pregnancy Association, the following factors of sexual intercourse may increase pregnancy chances:

- The woman raising her hips about 3 to 4 inches in order to allow gravity to assist with drawing the sperm towards the cervix opening and into the uterus, but there is no scientific data that confirms any beneficial effect of this practice.[16]

- Having sexual intercourse in the morning, by providing the best sperm quality.[16]

- Avoiding hot tubs before sex because the high temperature is harmful to sperm.[16]

- Avoiding vaginal douching before or after sex because the altered vaginal acidity is harmful to sperm, and washes away the fertility-beneficial cervical mucus.[16]

- Avoiding lubricants unless they are sperm-friendly.[16]

Pregnancy rate for artificial insemination

Generally, the pregnancy rate for artificial insemination is 10–15% per menstrual cycle using ICI,[17] and 15–20% per cycle for IUI.[17]

Pregnancy rate for in vitro fertilization

With enhanced technology, the pregnancy rates are substantially higher today[when?] than a couple of years ago. In 2006, Canadian clinics reported an average pregnancy rate of 35%.[5]

References

- ^ a b Liu J, Nagy Z, Joris H, et al. (October 1995). "Analysis of 76 total fertilization failure cycles out of 2732 intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles". Hum. Reprod. 10 (10): 2630–6. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135758. PMID 8567783.

- ^ Levi Setti, P. E.; Albani, E.; Matteo, M.; Morenghi, E.; Zannoni, E.; Baggiani, A. M.; Arfuso, V.; Patrizio, P. (2012). "Five years (2004-2009) of a restrictive law-regulating ART in Italy significantly reduced delivery rate: analysis of 10 706 cycles". Human Reproduction. 28 (2): 343–349. doi:10.1093/humrep/des404. ISSN 0268-1161. PMID 23175501.

- ^ About the Fertility Lab from Cleveland Clinic. Data from 2012

- ^ Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR (1999). "Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 340 (23): 1796–1799. doi:10.1056/NEJM199906103402304. PMID 10362823.

- ^ a b Success rate climbs for in vitro fertilization The Canadian Press. December 15, 2008 at 8:27 PM EST

- ^ te Velde, E. R. (2002). "The variability of female reproductive ageing and also on how the body is built". Human Reproduction Update. 8 (2): 141–154. doi:10.1093/humupd/8.2.141. ISSN 1355-4786. PMID 12099629.

- ^ Kidd SA, Eskenazi B, Wyrobek AJ (2001). "Effects of male age on semen quality and fertility: a review of the literature". Fertil Steril. 75 (2): 237–48. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(00)01679-4. PMID 11172821.

- ^ Dunson, D.B.; Baird, D.D.; Wilcox, A.J.; Weinberg, C.R. (1999). "Day-specific probabilities of clinical pregnancy based on two studies with imperfect measures of ovulation". Human Reproduction. 14 (7): 1835–1839. doi:10.1093/humrep/14.7.1835. ISSN 1460-2350. PMID 10402400.

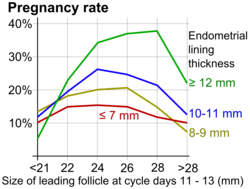

- ^ Palatnik, Anna; Strawn, Estil; Szabo, Aniko; Robb, Paul (2012). "What is the optimal follicular size before triggering ovulation in intrauterine insemination cycles with clomiphene citrate or letrozole? An analysis of 988 cycles". Fertility and Sterility. 97 (5): 1089–1094.e3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.018. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 22459633.

- ^ Pages .242,374 in: Weschler, Toni (2002). Taking Charge of Your Fertility (Revised ed.). New York: HarperCollins. pp. 359–361. ISBN 0-06-093764-5.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: LH urine test (home test)

- ^ a b "Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use:Fertility awareness-based methods". Third edition. World Health Organization. 2004. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Page 52 in: Weschler, Toni (2002). Taking Charge of Your Fertility (Revised ed.). New York: HarperCollins. pp. 359–361. ISBN 0-06-093764-5.

- ^ "How to get pregnant". Mayo Clinic. 2016-11-02. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ^ "Fertility problems: assessment and treatment, Clinical guideline [CG156]". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 2018-02-16. Published date: February 2013. Last updated: September 2017

- ^ a b c d e f Dr. Philip B. Imler & David Wilbanks. "The Essential Guide to Getting Pregnant" (PDF). American Pregnancy Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-01. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ^ a b Utrecht CS News Subject: Infertility FAQ (part 4/4)