Indica (Ancient Greek: Ἰνδικά Indika) is a book by the classical Greek physician Ctesias purporting to describe the Indian subcontinent.[1] Written in the fifth century BC, it is the first known Greek reference to that distant land. Ctesias was the court physician to king Artaxerxes II of Persia, and the book is not based on his own experiences, but on stories brought to Persia by traders, along the Silk Road from Serica, a land north of China and India where domesticated silk originated.

Contents

The book contains the first known reference to the unicorn, ostensibly an ass in India that had a single 1.5 cubit (27 inch) horn on its head, and introduces the European world to the talking parrot, and falconry, which was not yet practiced in Europe.

Among the information apparently conveyed in the book (mostly according to second-hand accounts of its contents):

- The Indus river is identified, and described as being up to twenty miles across.

- India is heavily populated, more than the rest of the world combined

- Indian elephants are first described, before Alexander the Great faced them while conquering part of India.

- While monkeys were well known in the Mediterranean, unusual types are described for India, including a tiny breed with a tail six feet in length

- Indian dogs the size of lions

- Gigantic mountains

- The martikhora (manticore), a red creature with a face like a man's, three rows of teeth, and a scorpion's sting on its tail. This is the earliest known Western reference to the manticore.

- Detailed descriptions of Indian customs, proclaiming them very just and honorable.

- Short, black men called pygmies, who live in the middle of India, who were two cubits tall. They raised livestock that was similarly small, and had a war going on with some cranes. These pygmies had grown their hair out to their knees and their beards past their feet, so long that they did not require any other clothing. When their body is thus entirely covered with hair they fasten it round them with a girdle, so that it serves them for clothes.

- Palm and date trees three times the size of those in Babylon

Legacy

Ctesias' books contains such a mix of obviously dubious apocrypha among its truths that it was sometimes mocked by subsequent authors as a source of wild yarns and myths. It has been argued that some fantastical descriptions may have been, in part, fabricated by Silk Road merchants seeking to increase the perceived value of their goods.[2]

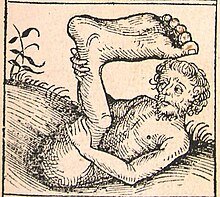

In the second century AD, the satirist Lucian depicted Ctesias as being condemned to a special part of hell reserved for those who spread wild lies during their lifetimes.[2] Indica apparently included such anecdotes as the description of a race of one-legged people called the Monosceli, another whose feet were so big they could be used as umbrellas (the Skiopolae), men with tails like satyrs, and claimed that people in the actual land of Serica (a word thought in some other cases to be the Greek word for part of China) were 18 feet tall.[3] Lucian's own similar book, A True Story, was presented as a satire of Indica, including an introduction that calls Ctesias and other similar authors inexperienced liars. Lucian states that he, himself, will now present a similar lie, but unlike his predecessors, he is at least honest enough to state this plainly up-front.

Conversely, the book did serve as the original source for a great deal of actual knowledge about the East that appears to have been completely absent in Western literature. Though only fragments exist today, its probable contents are very well-known because they were the main reference for Mediterranean knowledge of India, for centuries, and therefore are cited and quoted by many ancient authors whose works do survive to this day.

See also

References

- ^ "Ctesias of Cnidus - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2024-06-23.

- ^ a b Nichols, Andrew (2013-11-01). Ctesias: On India. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4725-1998-6.

- ^ Notes on the Indica of Ctesias