Jacques Lemercier | |

|---|---|

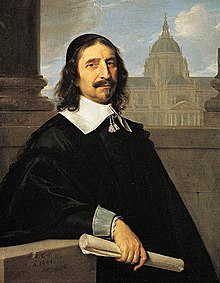

Jacques Lemercier in 1644 by Philippe de Champaigne with the Sorbonne Chapel in the background | |

| Born | c. 1585 Pontoise, France |

| Died | 13 January 1654 Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Practice | architect |

| Buildings | |

| Projects | Versailles |

Jacques Lemercier (French pronunciation: [ʒak ləmɛʁsje]; c. 1585 in Pontoise – 13 January 1654 in Paris) was a French architect and engineer, one of the influential trio that included Louis Le Vau and François Mansart who formed the classicizing French Baroque manner, drawing from French traditions of the previous century and current Roman practice the fresh, essentially French synthesis associated with Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIII.

Life and career

Lemercier was born in Pontoise. He was the son of a master mason, probably Nicolas Lemercier,[1][2] one of a large interrelated tribe of professionals. Profiting by a voyage to Italy with a long stay in Rome, presumably from about 1607 to 1610, Lemercier developed the simplified classicizing manner established by Salomon de Brosse, who died in 1636, and whose Palais du Luxembourg for Marie de Medici Lemercier would see to completion.

On his return to France, after several years working as an engineer building bridges, his first major commission, however, was to complete the Parisian Church of the Oratorians, (1616), which had been begun by Clément Métezeau; its success made his reputation. As early as 1618 he appears as architecte du roy, with a salary of 1200 livres, out of which he had to reimburse his atelier. In 1625 Richelieu put him in charge of the main royal project, the galleries being added to the Louvre, where Lemercier was working to the design established by Pierre Lescot a generation before; for the sake of regularity, Lescot's ranges in the Cour Carré were multiplied round further courtyards, quadrupling the building area, each of the four sides having a pavilion at its center. In this manner Lemercier built the northern half of the west side and the famous Pavillon de l'Horloge at the center of the west wing. Its high squared dome breaks the wing's roofline and three arched openings provide access to the enclosed court. Two superposed orders of columns and rich sculptural decor in pediments and niches, on piers and panels are kept under control by strong horizontal cornice lines.

During 1638 and 1639, Lemercier was appointed premier architecte charged with supervision of all the royal building enterprises, in which capacity he fell into a disagreeable dispute with the cultivated Nicolas Poussin about the decorations in the Louvre.

The Hôtel de Liancourt (1623) stands out among Lemercier's Paris hôtels particuliers for aristocratic patrons.

Lemercier built (from 1627 on) Richelieu's Paris residence, the Palais-Cardinal, today's Palais Royal. "Richelieu's palace was destroyed by fire in 1763. Only one remnant survives: a wall fragment with a relief of ship anchors and prows, signs of the Cardinal's role as Superintendent of the Navy, which appeared throughout the palace."[3] This remnant is located in the Galerie des Proues, on the east side of the second court (on the garden side), the so-called Cour d'Honneur.[4] A more expansive town-planning project, one of the most ambitious non-military French projects of the century, was the palatial residence, the grand parish church and the entire new town of Richelieu, in Poitou (Indre-et-Loire). The lost Château de Richelieu itself was an improvisation on the theme set by Brosse's Luxembourg. Also for the Cardinal Lemercier rebuilt the Château de Rueil, not so far from Paris, also demolished. The Château of Thouars, with its majestic long façade, is his also, and survives.

Less known, because gardens are less permanent, are parterre gardens laid out to Lemercier's designs, at Montjeu, at Richelieu and at Rueil (Mignot; Gady).

At the Sorbonne, the college has been rebuilt, but its domed church (1635) is the acknowledged surviving masterpiece of Lemercier. The hemispherical dome on a tall octagonal drum, first of its type in France, has four small cupolas in the angles of the Greek cross above the two Corinthian orders on the façade, of full columns below, flat pilasters above. The interior was intended to be frescoed. The square intersection is surrounded by cylindrical vaults and a semicircular choir apse. The north side consists of a portico. In the church Richelieu was interred in 1642.

At the royal abbey church of Val-de-Grâce Lemercier succeeded the elder Mansart who completed the structure to the cornice line, and refused to agree to a change in the building's design.[5] Lemercier completed it with a dome.

Lemercier was engaged by Louis XIII in initial planning for an expansion of the hunting lodge at Versailles, a project which was only realized by other architects, notably Louis Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart, under the guidance of Louis XIV.

One of his last commissions was the design of the Church of Saint-Roch, where the cornerstone was laid by Louis XIV in 1653. With a length of 126 m. it is one of the largest churches of Paris. the deep choir emphasizes the extent of the interior, scarcely interrupted by the discreet low dome over the crossing, which is hidden on the exterior beneath the transept roof. Lemercier completed the choir and crossing and the rest of the interior was carried out to his plan. Work was interrupted 1701–1740 save for a chapel inserted 1705–1710 designed by Jules Hardouin-Mansart. The present façade is an 18th-century composition by Robert de Cotte.

In a long career, the scrupulous Lemercier amassed no fortune. Through in 1645, Lemercier was receiving, as first among the royal architects (premier architecte du Roi), a salary of 3,000 livres, after his death— in the house he had built for himself, still standing at n° 46 rue de l’Arbre Sec (Gady)— it was necessary to sell the large library he had collected, in order to settle his debts.

Lemercier died in Paris. He was succeeded as first royal architect by Louis Le Vau.

See also

Other French architects of the first half of the 17th century:

Work

Saint-Jérôme Church in Toulouse

Notes

- ^ Sturgis, Russell (1901). A Dictionary of Architecture and Building, Volume II. New York: Macmillan. p. 739.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan (2016). The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199674992.

- ^ Ballon 2002, p. 247.

- ^ Not to be confused with a cour d'honneur, a term usually applied to the entrance court of an hôtel particulier.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Bibliography

- Ballon, Hilary (2002). "The Architecture of Cardinal Richelieu", pp. 246–259, in Richelieu: Art and Power, edited by Hilliard Todd Goldfarb. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. ISBN 9789053494073.

- Gady, Alexandre, 2005. Jacques Lemercier, architecte et ingénieur du roi ISBN 2-7351-1042-7 Review by Thierry Sarment. The first monograph devoted to Jacques Lemercier.

- Mignot, Claude (2004). "Jacques Lemercier" at culture.gouv.fr.