Sir James Douglas, 7th of Drumlanrig, (1498–1578) was a Scottish nobleman active in a turbulent time in Scotland's history.

Life

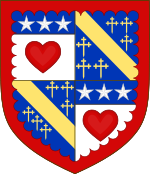

He was the son of Sir William Douglas, 6th of Drumlanrig (b. bef. 1484, k. 9 Sep 1513, Battle of Flodden) and Elizabeth Gordon of Lochinvar. As the descendant of William Douglas, 1st Earl of Douglas (b.1323 d.1384) and his first wife Margaret of Mar, he was a ‘Black Douglas’. Other descendants of the Earl from his mistress, Margaret Stewart, were known as ‘Red Douglas’. These two branches of the family were sometimes opposed, and this rivalry was revived in the time of the 7th Lord Drumlanrig.[1] Complicating matters was the fact that Drumlanrig's wife, Margaret, was the sister of the powerful ‘Red’ Earl of Angus, Archibald Douglas (b.1489 d.1557)

Guardianship of James V

One point of contention between Drumlanrig and Angus was over the guardianship of the infant King James V, whose father James IV had been killed at Flodden in 1513. His widow, Margaret Tudor, had quickly married the pro-English 6th Earl of Angus.[2] By doing so, she invalidated her position as tutrix (guardian) to her son, and this led to a tussle between her and the governor of the king's council, the pro-French John Stewart, Duke of Albany, over guardianship of the child.

Eventually her hasty marriage to the Earl of Angus was to devolve into a ‘long, acrimonious and very public separation’, ending in divorce.[3] She was therefore opposed to the guardianship by Angus over her son, after Albany's regency lapsed in 1524. At this point, Scotland had become ‘a Douglas kingdom in all but name',[4] with Angus ‘filling virtually all posts of authority with his relatives’.[4] James V was held as a virtual prisoner by Angus, leading to several failed attempts to free him. Drumlanrig was involved in one such attempt in July 1526, known as the Battle of Melrose.[5]

Only in 1528 did James, aged 16, free himself and assume authority over the kingdom. Despite his efforts two years previously to rescue him, Drumlanrig was considered by the new king ‘as one of a dangerous family’[6] and he was warded in Edinburgh Castle.

Return to favour

‘Thereafter little is heard of him till about the year 1550’,[6] although it is apparent he was working to significantly expand his sizeable family (see below). His return to favour after this year is apparent in the number of concessions granted to him by the government, acting in the name of Mary, Queen of Scots, who had left for France in 1548.

- In 1551 he was given a pardon for his part in the events of 1526.

- In 1552 he was appointed a commissioner to meet commissioners from England to discuss the border between the two countries.[7]

- In 1553 he was made Warden of the West Marches, with full powers of justiciary, an office he occupied for many years until retiring at an old age.[7]

Guardianship of Janet and Marion Carruthers

In 1548, after the death of Sir Simon Carruthers of Mouswald, he was made guardian of his two young daughters, Marion and Janet. He had responsibility for ensuring their upbringing and marriage. It is likely that he eyed their family property with a covetous eye, since he persuaded Janet, on marrying, to surrender part of her estate to him in exchange for money. Marion rejected both his choice of husband and his offer to buy her half of the estate, leading to an appeal by him to the Privy Council.[8] In 1564 she was found dead in an apparent suicide at the base of the battlements of Comlongon Castle, where she had gone to take refuge. The court eventually awarded her half of the estate to Drumlanrig's heir, William.[8]

The return of the Queen

In 1561, Mary Queen of Scots returned to Scotland. Drumlanrig was probably not a natural adherent of the Queen, being a Protestant whilst Mary was a Catholic. Along with John Knox, Drumlanrig had signed the First Book of Discipline in Edinburgh this same year,[7] described by a later historian as ‘an owner’s manual for the new religion’.[9] (Drumlanrig was also one of those who visited John Knox on his deathbed in 1572)

Concerned that her marriage to the Catholic Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley heralded a return to the Catholic religion, he joined other Protestant lords in a faint-hearted rebellion in 1565, later called the ‘Chaseabout Raid’.

When the King and Queen advanced in force upon Dumfries, most of the Protestant lords went off to Carlisle, but Maxwell, Drumlanrig and Gordon of Lochinvar remained to meet their sovereign, and Mary won them over to her side.[6]

Two years later, after the death of Mary Queen of Scot's husband Lord Darnley (a relation of Drumlanrig's wife Margaret), and Mary's quick remarriage to the Earl of Bothwell, Drumlanrig again joined the Protestant ‘Confederate Lords’ in revolt.This saw her (much smaller) army capitulate without a fight at Carberry Hill in June 1567.[10] The Queen later spoke bitterly about both Drumlanrig and his son William, describing them as ‘hell houndis, bludy tyrantis without saullis or feir of God’.[7] An aftershock of his opposition to Mary arose in 1571, when following a dispute with the Laird of Wormiston (a supporter of Queen Mary), he was ambushed and taken prisoner. Whilst in prison, he wrote a touching letter to his son, whose fate he was unsure of.

Willie, Thou sall wit that I am haill and feare. Send me word thairfoir how thow art, whether deid or livand? Gif thow be deid, I doubt not but freindis will let me know the treuth; and gif thow be weill, I desire na muir,”[11]

Marriage and issue

On his death in 1578, it is said that he had ‘raised his family to a very high degree of influence in the south-west of Scotland’.[12] He had 18 children by 2 wives and mistresses. His first wife was Margaret Douglas, sister to the Earl of Angus, with whom he had 10 children. Divorced c. 1539, he married Christian Montgomery, who became mother to another 6 of his children, including his heir, William Douglas of Hawick. Because William predeceased his father, the title and estate was inherited by Drumlanrig's grandson, James Douglas.

Robert Douglas, Provost of Lincluden was his son by one of his mistresses.[13]

References

- ^ Maxwell, Herbert (1902). A History of the House of Douglas from the Earliest Times Down to the Legislative Union of England and Scotland. London: Fremantle & Co. p. 251.

- ^ Oliver, Neil (2009). A History of Scotland. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-7538-2663-8.

- ^ Lynch, Michael (1991). Scotland. A New History. London: Pimlico. pp. 162. ISBN 9780712698931.

- ^ a b Ross, David (2008). Scotland. History of a Nation. New Lanark: Lomond Books. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-947782-58-0.

- ^ Maxwell, Herbert (1902). A History of the House of Douglas... p. 251.

- ^ a b c Maxwell, Herbert (1902). A History of the Douglas... p. 252.

- ^ a b c d Ramage, Craufurd Tait (1876). Drumlanrig Castle and the Douglases. Dumfries: J.Anderson & Son. p. 41.

- ^ a b Maxwell, Herbert (1902). A History of the House of Douglas... p. 254.

- ^ Oliver, Neil (2009). A History of Scotland. p. 221.

- ^ Ross, David (2008). Scotland. History of a Nation. p. 160.

- ^ Ramage, Craufurd Tate (1876). Drumlanrig Castle and the Douglases: with the Early History and Ancient Remains of Durisdeer, Closeburn and Morton. Dumfries: J.Anderson & Son. p. 42.

- ^ Maxwell, Herbert (1902). A History of the House of Douglas... p. 259.

- ^ David Laing, Works of John Knox, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1848), p. 386 fn.