During World War II, it was estimated that between 35,000 and 50,000 members of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces surrendered to Allied service members prior to the end of World War II in Asia in August 1945.[1] Also, Soviet troops seized and imprisoned more than half a million Japanese troops and civilians in China and other places.[2] The number of Japanese soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen who surrendered was limited by the Japanese military indoctrinating its personnel to fight to the death, Allied combat personnel often being unwilling to take prisoners,[3] and many Japanese soldiers believing that those who surrendered would be killed by their captors.[4][5]

Western Allied governments and senior military commanders directed that Japanese POWs be treated in accordance with relevant international conventions. In practice though, many Allied soldiers were unwilling to accept the surrender of Japanese troops because of atrocities committed by the Japanese. A campaign launched in 1944 to encourage prisoner-taking was partially successful, and the number of prisoners taken increased significantly in the last year of the war.

Japanese POWs often believed that by surrendering they had broken all ties with Japan, and many provided military intelligence to the Allies. The prisoners taken by the Western Allies were held in generally good conditions in camps located in Australia, New Zealand, India and the United States. Those taken by the Soviet Union were treated harshly in work camps located in Siberia. Following the war the prisoners were repatriated to Japan, though the United States and Britain retained thousands until 1946 and 1947 respectively and the Soviet Union continued to hold hundreds of thousands of Japanese POWs until the early 1950s. The Soviet Union gradually released some POWs throughout the next few decades, but some did not return until the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, while others who had settled and started families in the Soviet Union opted to remain.[2]

Japanese attitudes to surrender

During the 1920s and 1930s, the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) adopted an ethos which required soldiers to fight to the death rather than surrender.[6] This policy reflected the practices of Japanese warfare in the pre-modern era.[7] During the Meiji period the Japanese government adopted western policies towards POWs, and few of the Japanese personnel who surrendered in the Russo-Japanese War were punished at the end of the war. Prisoners captured by Japanese forces during this and the First Sino-Japanese War and World War I were also treated in accordance with international standards.[8] The relatively good treatment that prisoners in Japan received was used as a propaganda tool, exuding a sense of "chivalry" in comparison to the more barbaric perception of Asia that the Meiji government wished to avoid.[9] Attitudes towards surrender hardened after World War I. While Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention covering treatment of POWs, it did not ratify the agreement, claiming that surrender was contrary to the beliefs of Japanese soldiers. This attitude was reinforced by the indoctrination of young people.[10]

The Japanese military's attitude towards surrender was institutionalized in the 1941 "Code of Battlefield Conduct" (Senjinkun), which was issued to all Japanese soldiers. This document sought to establish standards of behavior for Japanese troops and improve discipline and morale within the Army, and included a prohibition against being taken prisoner.[13] The Japanese Government accompanied the Senjinkun's implementation with a propaganda campaign which celebrated people who had fought to the death rather than surrender during Japan's wars.[14] While the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) did not issue a document equivalent to the Senjinkun, naval personnel were expected to exhibit similar behavior and not surrender.[15] Most Japanese military personnel were told that they would be killed or tortured by the Allies if they were taken prisoner.[16] The Army's Field Service Regulations were also modified in 1940 to replace a provision which stated that seriously wounded personnel in field hospitals came under the protection of the 1929 Geneva Convention for the Sick and Wounded Armies in the Field with a requirement that the wounded not fall into enemy hands. During the war, this led to wounded personnel being either killed by medical officers or given grenades to commit suicide.[17] Aircrew from Japanese aircraft which crashed over Allied-held territory also typically committed suicide rather than allow themselves to be captured.[18]

Those who know shame are weak. Always think of [preserving] the honor of your community and be a credit to yourself and your family. Redouble your efforts and respond to their expectations. Never live to experience shame as a prisoner. By dying you will avoid leaving a stain on your honor.

While scholars disagree over whether the Senjinkun was legally binding on Japanese soldiers, the document reflected Japan's societal norms and had great force over both military personnel and civilians. In 1942 the Army amended its criminal code to specify that officers who surrendered soldiers under their command faced at least six months imprisonment, regardless of the circumstances in which the surrender took place. This change attracted little attention, however, as the Senjinkun imposed more severe consequences and had greater moral force.[15]

The indoctrination of Japanese military personnel to have little respect for the act of surrendering led to conduct which Allied soldiers found deceptive. During the Pacific War, there were incidents where Japanese soldiers feigned surrender in order to lure Allied troops into ambushes. In addition, wounded Japanese soldiers sometimes tried to use hand grenades to kill Allied troops attempting to assist them.[19] Japanese attitudes towards surrender also contributed to the harsh treatment which was inflicted on the Allied personnel they captured.[20]

Not all Japanese military personnel chose to follow the precepts set out on the Senjinkun. Those who chose to surrender did so for a range of reasons including not believing that suicide was appropriate or lacking the will to commit the act, bitterness towards officers, and Allied propaganda promising good treatment.[21] During the later years of the war Japanese troops' morale deteriorated as a result of Allied victories, leading to an increase in the number who were prepared to surrender or desert.[22] During the Battle of Okinawa, 11,250 Japanese military personnel (including 3,581 unarmed labourers) surrendered between April and July 1945, representing 12 percent of the force deployed for the defense of the island. Many of these men were recently conscripted members of Boeitai home guard units who had not received the same indoctrination as regular Army personnel, but substantial numbers of IJA soldiers also surrendered.[23]

Japanese soldiers' reluctance to surrender was also influenced by a perception that Allied forces would kill them if they did surrender, and historian Niall Ferguson has argued that this had a more important influence in discouraging surrenders than the fear of disciplinary action or dishonor.[5] In addition, the Japanese public was aware that US troops sometimes mutilated Japanese casualties and sent trophies made out of body-parts home from media reports of two high-profile incidents in 1944 in which a letter-opener carved from a bone of a Japanese soldier was presented to President Roosevelt and a photo of the skull of a Japanese soldier which had been sent home by a US soldier was published in the magazine Life. In these reports Americans were portrayed as "deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman".[24] Hoyt in "Japan’s war: the great Pacific conflict" argues that the Allied practice of taking bones from Japanese corpses home as souvenirs was exploited by Japanese propaganda very effectively, and "contributed to a preference to death over surrender and occupation, shown, for example, in the mass civilian suicides on Saipan and Okinawa after the Allied landings".[24]

The causes of the phenomenon that Japanese often continued to fight even in hopeless situations has been traced to a combination of Shinto, messhi hōkō (self-sacrifice for the sake of group), and Bushido. However, a factor equally strong or even stronger to those, was the fear of torture after capture. This fear grew out of years of battle experiences in China, where the Chinese guerrillas were considered expert torturers, and this fear was projected onto the American soldiers who also were expected to torture and kill surrendered Japanese.[25] During the Pacific War the majority of Japanese military personnel did not believe that the Allies treated prisoners correctly, and even a majority of those who surrendered expected to be killed.[26]

Allied attitudes

The Western Allies sought to treat captured Japanese in accordance with international agreements which governed the treatment of POWs.[20] Shortly after the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941, the British and United States governments transmitted a message to the Japanese government through Swiss intermediaries asking if Japan would abide by the 1929 Geneva Convention. The Japanese Government responded stating that while it had not signed the convention, Japan would treat POWs in accordance with its terms; in effect though, Japan had willfully ignored the convention's requirements. While the Western Allies notified the Japanese government of the identities of Japanese POWs in accordance with the Geneva Convention's requirements, this information was not passed onto the families of the captured men as the Japanese government wished to maintain that none of its soldiers had been taken prisoner.[27]

Allied combatants were reluctant to take Japanese prisoners at the start of the Pacific War. During the first two years following the US entry into the war, US combatants were generally unwilling to accept the surrender of Japanese soldiers due to a combination of racist attitudes and anger at Japan's war crimes committed against US and Allied nationals such as its widespread mistreatment or summary execution of Allied POWs.[20][28] Australian soldiers were also reluctant to take Japanese prisoners for similar reasons.[29] Incidents in which Japanese soldiers booby-trapped their dead and wounded or pretended to surrender in order to lure Allied combatants into ambushes were well known within the Allied militaries and also hardened attitudes against seeking the surrender of Japanese on the battlefield.[30] As a result, Allied troops believed that their Japanese opponents would not surrender and that any attempts to surrender were deceptive;[31] for instance, the Australian jungle warfare school advised soldiers to shoot any Japanese troops who had their hands closed while surrendering.[29] Furthermore, in many instances, Japanese soldiers who had surrendered were killed on the front line or while being taken to POW compounds.[32] The nature of jungle warfare also contributed to prisoners not being taken, as many battles were fought at close ranges where participants "often had no choice but to shoot first and ask questions later".[33]

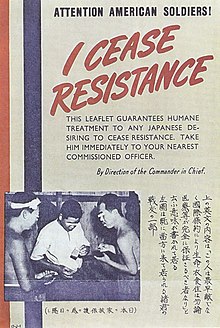

Despite the attitudes of combat troops and nature of the fighting, Allied militaries made systematic efforts to take Japanese prisoners throughout the war. Each US Army division was assigned a team of Japanese Americans whose duties included attempting to persuade Japanese personnel to surrender.[34] Allied forces mounted an extensive psychological warfare campaign against their Japanese opponents to lower their morale and encourage surrender.[35] This included dropping copies of the Geneva Conventions and 'surrender passes' on Japanese positions.[36] This campaign was undermined by Allied troops' reluctance to take prisoners, however.[37] As a result, from May 1944, senior US Army commanders authorized and endorsed educational programs which aimed to change the attitudes of front line troops. These programs highlighted the intelligence which could be gained from Japanese POWs, the need to honor surrender leaflets, and the benefits which could be gained by encouraging Japanese forces to not fight to the last man. The programs were partially successful, and contributed to US troops taking more prisoners. In addition, soldiers who witnessed Japanese troops surrender were more willing to take prisoners themselves.[38]

Survivors of ships sunk by Allied submarines frequently refused to surrender, and many of the prisoners who were captured by submariners were taken by force. US Navy submarines were occasionally ordered to obtain prisoners for intelligence purposes, and formed special teams of personnel for this purpose.[39] Overall, however, Allied submariners usually did not attempt to take prisoners, and the number of Japanese personnel they captured was relatively small. The submarines which took prisoners normally did so towards the end of their patrols so that they did not have to be guarded for a long time.[40]

Allied forces continued to kill many Japanese personnel who were attempting to surrender throughout the war.[41] It is likely that more Japanese soldiers would have surrendered if they had not believed that they would be killed by the Allies while trying to do so.[3] Fear of being killed after surrendering was one of the main factors which influenced Japanese troops to fight to the death, and a wartime US Office of Wartime Information report stated that it may have been more important than fear of disgrace and a desire to die for Japan.[42] Instances of Japanese personnel being killed while attempting to surrender are not well documented, though anecdotal accounts provide evidence that this occurred.[28]

Prisoners taken during the war

Estimates of the numbers of Japanese personnel taken prisoner during the Pacific War differ.[1][28] Japanese historian Ikuhiko Hata states that up to 50,000 Japanese became POWs before Japan's surrender.[43] The Japanese Government's wartime POW Information Bureau believed that 42,543 Japanese surrendered during the war;[17] a figure also used by Niall Ferguson who states that it refers to prisoners taken by United States and Australian forces.[44] Ulrich Straus states that about 35,000 were captured by western Allied and Chinese forces,[45] and Robert C. Doyle gives a figure of 38,666 Japanese POWs in captivity in camps run by the western Allies at the end of the war.[46] Alison B. Gilmore has also calculated that Allied forces in the South West Pacific Area alone captured at least 19,500 Japanese.[47]a

It has been estimated that at the end of the war Chinese Nationalist and Communist forces held 22,293 Japanese prisoners prior to August 1945.[48] The conditions these POWs were held in generally did not meet the standards required by international law. The Japanese government expressed no concern for these abuses, however, as it did not want IJA soldiers to even consider surrendering. The government was, however, concerned about reports that 300 POWs had joined the Chinese Communists and had been trained to spread anti-Japanese propaganda.[49]

The Japanese government sought to suppress information about captured personnel. On 27 December 1941, it established a POW Information Bureau within the Ministry of the Army to manage information concerning Japanese POWs. While the Bureau cataloged information provided by the Allies via the Red Cross identifying POWs, it did not pass this information on to the families of the prisoners. When individuals wrote to the Bureau to inquire if their relative had been taken prisoner, it appears that the Bureau provided a reply which neither confirmed or denied whether the man was a prisoner. Although the Bureau's role included facilitating mail between POWs and their families, this was not carried out as the families were not notified and few POWs wrote home. The lack of communication with their families increased the POWs feelings of being cut off from Japanese society.[50]

Intelligence gathered from Japanese POWs

The Allies gained considerable quantities of intelligence from Japanese POWs. Because they had been indoctrinated to believe that by surrendering they had broken all ties with Japan, many captured personnel provided their interrogators with information on the Japanese military.[43] Australian and US troops and senior officers commonly believed that captured Japanese troops were very unlikely to divulge any information of military value, leading to them having little motivation to take prisoners.[52] This view proved incorrect, however, and many Japanese POWs provided valuable intelligence during interrogations. Few Japanese were aware of the Geneva Convention and the rights it gave prisoners to not respond to questioning. Moreover, the POWs felt that by surrendering they had lost all their rights. The prisoners appreciated the opportunity to converse with Japanese-speaking Americans and felt that the food, clothing and medical treatment they were provided with meant that they owed favours to their captors. The Allied interrogators found that exaggerating the amount they knew about the Japanese forces and asking the POWs to 'confirm' details was also a successful approach. As a result of these factors, Japanese POWs were often cooperative and truthful during interrogation sessions.[53]

Japanese POWs were interrogated multiple times during their captivity. Most Japanese soldiers were interrogated by intelligence officers of the battalion or regiment which had captured them for information which could be used by these units. Following this they were rapidly moved to rear areas where they were interrogated by successive echelons of the Allied military. They were also questioned once they reached a POW camp in Australia, New Zealand, India or the United States. These interrogations were painful and stressful for the POWs.[54] Similarly, Japanese sailors rescued from sunken ships by the US Navy were questioned at the Navy's interrogation centres in Brisbane, Honolulu and Noumea.[55] Allied interrogators found that Japanese soldiers were much more likely to provide useful intelligence than Imperial Japanese Navy personnel, possibly due to differences in the indoctrination provided to members of the services.[55] Force was not used in interrogations at any level, though on one occasion headquarters personnel of the US 40th Infantry Division debated, but ultimately decided against, administering sodium penthanol to a senior non-commissioned officer.[56]

Some Japanese POWs also played an important role in helping the Allied militaries develop propaganda and politically indoctrinate their fellow prisoners.[57] This included developing propaganda leaflets and loudspeaker broadcasts which were designed to encourage other Japanese personnel to surrender. The wording of this material sought to overcome the indoctrination which Japanese soldiers had received by stating that they should "cease resistance" rather than "surrender".[58] POWs also provided advice on the wording for propaganda leaflets which were dropped on Japanese cities by heavy bombers in the final months of the war.[59]

Allied prisoner of war camps

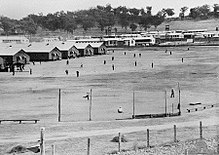

Japanese POWs held in Allied prisoner of war camps were treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention.[60] By 1943 the Allied governments were aware that personnel who had been captured by the Japanese military were being held in harsh conditions. In an attempt to win better treatment for their POWs, the Allies made extensive efforts to notify the Japanese government of the good conditions in Allied POW camps.[61] This was not successful, however, as the Japanese government refused to recognise the existence of captured Japanese military personnel.[62] Nevertheless, Japanese POWs in Allied camps continued to be treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions until the end of the war.[63]

Most Japanese captured by US forces after September 1942 were turned over to Australia or New Zealand for internment. The United States provided these countries with aid through the Lend Lease program to cover the costs of maintaining the prisoners, and retained responsibility for repatriating the men to Japan at the end of the war. Prisoners captured in the central Pacific or who were believed to have particular intelligence value were held in camps in the United States.[64]

Prisoners who were thought to possess significant technical or strategic information were brought to specialist intelligence-gathering facilities at Fort Hunt, Virginia or Camp Tracy, California. After arriving in these camps, the prisoners were interrogated again, and their conversations were wiretapped and analysed. Some of the conditions at Camp Tracy violated Geneva Convention requirements, such as insufficient exercise time being provided. However, prisoners at this camp were given special benefits, such as high quality food and access to a shop, and the interrogation sessions were relatively relaxed. The continuous wiretapping at both locations may have also violated the spirit of the Geneva Convention.[66]

Japanese POWs generally adjusted to life in prison camps and few attempted to escape.[67] There were several incidents at POW camps, however. On 25 February 1943, POWs at the Featherston prisoner of war camp in New Zealand staged a strike after being ordered to work. The protest turned violent when the camp's deputy commander shot one of the protest's leaders. The POWs then attacked the other guards, who opened fire and killed 48 prisoners and wounded another 74. Conditions at the camp were subsequently improved, leading to good relations between the Japanese and their New Zealand guards for the remainder of the war.[68] More seriously, on 5 August 1944, Japanese POWs in a camp near Cowra, Australia attempted to escape. During the fighting between the POWs and their guards 257 Japanese and 4 Australians were killed.[69] Other confrontations between Japanese POWs and their guards occurred at Camp McCoy in Wisconsin during May 1944 as well as a camp in Bikaner, India during 1945; these did not result in any fatalities.[70] In addition, 24 Japanese POWs killed themselves at Camp Paita, New Caledonia in January 1944 after a planned uprising was foiled.[71] News of the incidents at Cowra and Featherston was suppressed in Japan,[72] but the Japanese Government lodged protests with the Australian and New Zealand governments as a propaganda tactic. This was the only time that the Japanese Government officially recognized that some members of the country's military had surrendered.[73]

The Allies distributed photographs of Japanese POWs in camps to induce other Japanese personnel to surrender. This tactic was initially rejected by General Douglas MacArthur when it was proposed to him in mid-1943 on the grounds that it violated the Hague and Geneva Conventions, and the fear of being identified after surrendering could harden Japanese resistance. MacArthur reversed his position in December of that year, however, but only allowed the publication of photos that did not identify individual POWs. He also directed that the photos "should be truthful and factual and not designed to exaggerate".[74]

Post-war

Millions of Japanese military personnel surrendered following the end of the war. Soviet and Chinese forces accepted the surrender of 1.6 million Japanese and the western allies took the surrender of millions more in Japan, South-East Asia and the South-West Pacific.[75] In order to prevent resistance to the order to surrender, Japan's Imperial Headquarters included a statement that "servicemen who come under the control of enemy forces after the proclamation of the Imperial Rescript will not be regarded as POWs" in its orders announcing the end of the war. While this measure was successful in avoiding unrest, it led to hostility between those who surrendered before and after the end of the war and denied prisoners of the Soviets POW status. In most instances the troops who surrendered were not taken into captivity, and were repatriated to the Japanese home islands after giving up their weapons.[43]

Repatriation of some Japanese POWs was delayed by Allied authorities. Until late 1946, the United States retained almost 70,000 POWs to dismantle military facilities in the Philippines, Okinawa, central Pacific, and Hawaii. British authorities retained 113,500 of the approximately 750,000 POWs in south and south-east Asia until 1947; the last POWs captured in Burma and Malaya returned to Japan in October 1947.[76] The British also used armed Japanese Surrendered Personnel to support Dutch and French attempts to reassert control in the Dutch East Indies and Indochina respectively.[77] At least 81,090 Japanese personnel died in areas occupied by the western Allies and China before they could be repatriated to Japan. Historian John W. Dower has attributed these deaths to the "wretched" condition of Japanese military units at the end of the war.[78][79]

China

Nationalist Chinese forces took the surrender of 1.2 million Japanese military personnel following the war. While the Japanese feared that they would be subjected to reprisals, they were generally treated well. This was because the Nationalists wished to seize as many weapons as possible, ensure that the departure of the Japanese military did not create a security vacuum and discourage Japanese personnel from fighting alongside the Chinese communists.[80] Over the next few months, most Japanese prisoners in China, along with Japanese civilian settlers, were returned to Japan. The Nationalists retained over 50,000 POWs, most of whom had technical skills, until the second half of 1946, however. Tens of thousands of Japanese prisoners captured by Chinese communists were serving in their military forces in August 1946 and more than 60,000 were believed to still be held in Communist-controlled areas as late as April 1949.[76] Hundreds of Japanese POWs were killed fighting for the People's Liberation Army during the Chinese Civil War. Following the war, the victorious Chinese Communist government began repatriating Japanese prisoners home, though some were put on trial for war crimes and had to serve prison sentences of varying length before being allowed to return. The last Japanese prisoner returned from China in 1964.[81][82]

Soviet Union

Hundreds of thousands of Japanese also surrendered to Soviet forces in the last weeks of the war and after Japan's surrender. The Soviet Union claimed to have taken 594,000 Japanese POWs, of whom 70,880 were immediately released, but Japanese researchers have estimated that 850,000 were captured.[28] Unlike the prisoners held by China or the western Allies, these men were treated harshly by their captors, and over 60,000 died by Russian sources. Some American historians estimate that at least 250,000 people died.[83] Japanese POWs were forced to undertake hard labour and were held in primitive conditions with inadequate food and medical treatments. This treatment was similar to that experienced by German POWs in the Soviet Union.[84] The treatment of Japanese POWs in Siberia was also similar to that suffered by Soviet prisoners who were being held in the area.[85] Between 1946 and 1950, many of the Japanese POWs in Soviet captivity were released; those remaining after 1950 were mainly those convicted of various crimes. They were gradually released under a series of amnesties between 1953 and 1956. After the last major repatriation in 1956, the Soviets continued to hold some POWs and release them in small increments. Some ended up spending decades living in the Soviet Union, and could only return to Japan in the 1990s. Some, having spent decades away and having started families of their own, elected not to permanently settle in Japan and remain where they were.[2][86]

Due to the shame associated with surrendering, few Japanese POWs wrote memoirs after the war.[28]

See also

- Japanese prisoners of war in the Soviet Union

- Japanese Surrendered Personnel

- Internment of Japanese Americans

- Takenaga incident

Notes

^a Gilmore provides the following numbers of Japanese POWs taken in the SWPA during each year of the war –

- 1942: 1,167

- 1943: 1,064

- 1944: 5,122

- 1945: 12,194[47]

Footnotes

- ^ a b Fedorowich (2000), p. 61

- ^ a b c Kristof, Nicholas D. (12 April 1998). "Japan's Blossoms Soothe a P.O.W. Lost in Siberia". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Bergerud (1997), pp. 415–16

- ^ Johnston (2000), p. 81

- ^ a b Ferguson (2004), p. 176.

- ^ Drea (2009), p. 257

- ^ Strauss (2003), pp. 17–19

- ^ Strauss (2003), pp. 20–21

- ^ "MIT Visualizing Cultures". visualizingcultures.mit.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-03.

- ^ Strauss (2003), pp. 21–22

- ^ "Australian War Memorial 013968". Collection database. Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ McCarthy (1959), p. 450

- ^ Drea (2009), p. 212

- ^ a b Straus (2003), p. 39

- ^ a b Straus (2003), p. 40

- ^ Dower (1986), p. 77

- ^ a b Hata (1996), p. 269

- ^ Ford (2011), p. 139

- ^ Doyle (2010), p. 206

- ^ a b c Straus (2003), p. 3

- ^ Strauss (2003), pp. 44–45

- ^ Gilmore (1998), pp. 2, 8

- ^ Hayashi (2005), pp. 51–55

- ^ a b Harrison, p. 833

- ^ Interrogation: World War II, Vietnam, and Iraq, National Defense Intelligence College, Washington, DC. (2008), ISBN 978-1932946239, pp. 31–34

- ^ Gilmore (1998), p. 169

- ^ Straus (2003), p. 29

- ^ a b c d e La Forte (2000), p. 333

- ^ a b Johnston (2000), p. 95

- ^ Dower (1986), p. 64

- ^ Gilmore (1998), p. 61

- ^ Dower (1986), p. 69

- ^ Johnston (1996), p. 40

- ^ Bergerud (2008), p. 103

- ^ Gilmore (1998), p. 2

- ^ Ferguson (2007), p. 550

- ^ Gilmore (1998), pp. 62–63

- ^ Gilmore (1998), pp. 64–67

- ^ Sturma (2011), p. 147

- ^ Sturma (2011), p. 151

- ^ Ferguson (2007), p. 544

- ^ Dower (1986), p. 68

- ^ a b c Hata (1996), p. 263

- ^ Ferguson (2004), p. 164

- ^ Straus (2003), p. ix

- ^ Doyle (2010), p. 209

- ^ a b Gilmore (1998), p. 155

- ^ ed. Coox, Alvin and Hilary Conroy "China and Japan: A Search for Balance since World War I", pp. 308.

- ^ Straus (2003), p. 24

- ^ Hata (1996), p. 265

- ^ Gilmore (1998), p. 172

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. 116, 141

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. 141–47

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. 126–27

- ^ a b Ford (2011), p. 100

- ^ Straus (2003), p. 120

- ^ Fedorowich (2000), p. 85

- ^ Doyle (2010), p. 212

- ^ Doyle (2010), p. 213

- ^ MacKenzie (1994), p. 512

- ^ MacKenzie (1994), p. 516

- ^ MacKenzie (1994), pp. 516–17

- ^ MacKenzie (1994), p. 518

- ^ Krammer (1983), p. 70

- ^ "Australian War Memorial – 067178". Collection database. Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. 134–39

- ^ Straus (2003), p. 197

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. 176–78

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. 186–91

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. 191–95

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. 178–86

- ^ MacKenzie (1994), p. 517

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. 193–94

- ^ Fedorowich (2000), pp. 80–81

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. xii–xiii

- ^ a b Dower (1999), p. 51

- ^ Kibata (2000), p. 146

- ^ Dower (1986), p. 298 and note 6, p. 363

- ^ MacArthur (1994), p. 130, note 36

- ^ Straus (2003), pp. xiii–xiv

- ^ Lynch, Michael: The Chinese Civil War 1945–49

- ^ Coble, Parks M.: China's War Reporters, p. 143

- ^ Nimmo, William F.: Behind a Curtain of Silence: Japanese in Soviet Custody, 1945-1956

- ^ Straus (2003), p. xiv

- ^ La Forte (2000), p. 335

- ^ "The last Japanese man remaining in Kazakhstan: A Kafkian tale of the plight of a Japanese POW in the Soviet Union". 7 February 2011.

References

- Aldrich, Richard J. (2005). The Faraway War: Personal Diaries of the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific. London: Doubleday. ISBN 0385606796.

- Bergerud, Eric (1997). Touched with Fire. The Land War in the South Pacific. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140246967.

- Bergerud, Eric (2008). "No Quarter. The Pacific Battlefield". In Yerxa, Donald A. (ed.). Recent Themes in Military History: Historians in Conversation. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1570037399.

- Carr-Gregg, Charlotte (1978). Japanese Prisoners of War in Revolt. The Outbreaks at Featherston and Cowra during World War II. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 0702212261.

- Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy. Race and Power in the Pacific War. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 039450030X.

- Dower, John W. (1999). Embracing Defeat. Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: W.W. Norton & Company / The New Press. ISBN 0393046869.

- Doyle, Robert C. (2010). The Enemy in Our Hands: America's Treatment of Enemy Prisoners of War, from the Revolution to the War on Terror. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813134604.

- Drea, Edward J. (1989). "In the Army Barracks Of Imperial Japan". Armed Forces & Society. 15 (3). Inter-University Seminar on Armed Forces and Society: 329–48. doi:10.1177/0095327X8901500301. ISSN 1556-0848. S2CID 144370000.

- Drea, Edward J. (2009). Japan's Imperial Army. Its Rise and Fall, 1853–1945. Modern War Studies. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0700616633.

- Fedorowich, Fred (2000). "Understanding the Enemy: Military Intelligence, Political Warfare and Japanese Prisoners of War in Australia, 1942–45". In Towle, Philip; Kosuge, Margaret; Kibata Yōichi (eds.). Japanese prisoners of war. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1852851929.

- Ferguson, Niall (2004). "Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat". War in History. 11 (2). SAGE Publications: 148–92. doi:10.1191/0968344504wh291oa. ISSN 1477-0385. S2CID 159610355.

- Ferguson, Niall (2007). The War of the World. History's Age of Hatred. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0141013824.

- Ford, Douglas (May 2010). "US Perceptions of Military Culture and the Japanese Army's Performance During the Pacific War". War & Society. 29 (1). Maney Publishing: 71–93. doi:10.1179/204243410X12674422128911. ISSN 0729-2473. S2CID 155012892.

- Ford, Douglas (2011). The Elusive Enemy : U.S. Naval Intelligence and the Imperial Japanese Fleet. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1591142805.

- Frank, Richard B. (2001). Downfall. The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0141001461.

- Gilmore, Allison B. (1995). ""We Have Been Reborn": Japanese Prisoners and the Allied Intelligence War in the Southwest Pacific". Pacific Historical Review. 64 (2). Berkeley: University of California Press. doi:10.2307/3640895. JSTOR 3640895.

- Gilmore, Allison B. (1998). You can't fight tanks with bayonets: psychological warfare against the Japanese Army in the Southwest Pacific. Studies in war, society, and the military. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803221673.

- Hata, Ikuhiko (1996). "From Consideration to Contempt: The Changing Nature of Japanese Military and Popular Perceptions of Prisoners of War Through the Ages". In Moore, Bob; Fedorowich, Kent (eds.). Prisoners of War and Their Captors in World War II. Oxford: Berg. ISBN 185973152X.

- Hayashi, Hirofumi (2005). "Japanese Deserters and Prisoners of War in the Battle of Okinawa". In Moore, Bob; Hately-Broad, Barbara (eds.). Prisoners of War, Prisoners of Peace: Captivity, Homecoming, and Memory in World War II. New York: Berg. pp. 34–58.

- Johnston, Mark (1996). At the Front Line. Experiences of Australian Soldiers in World War II. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521560373.

- Johnston, Mark (2000). Fighting the enemy: Australian soldiers and their adversaries in World War II. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521782228.

- Kibata, Yoichi (2000). "Japanese Treatment of British Prisoners of War: The Historical Context". In Towle, Philip; Kosuge, Margaret; Kibata Yōichi (eds.). Japanese prisoners of war. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1852851929.

- Krammer, Arnold (1983). "Japanese Prisoners of War in America". Pacific Historical Review. 52 (52). Berkeley: University of California Press: 67–91. doi:10.2307/3639455. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3639455.

- La Forte, Robert S. (2000). "World War II–Far East". In Vance, Jonathan F (ed.). Encyclopedia of Prisoners of War and Internment. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576070689.

- MacArthur, Douglas (1994). MacArthur in Japan: The Occupation: Military Phase. Reports of General MacArthur. Washington D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History.

- MacKenzie, S.P. (1994). "The Treatment of Prisoners of War in World War II". The Journal of Modern History. 66 (3). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press: 487–520. doi:10.1086/244883. ISSN 0022-2801. S2CID 143467546.

- McCarthy, Dudley (1959). South–West Pacific Area – First Year: Kokoda to Wau. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 2009-05-25.

- Straus, Ulrich (2003). The Anguish of Surrender: Japanese POWs of World War II. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295983361.

- Sturma, Michael (2011). Surface and Destroy : The Submarine Gun War in the Pacific. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813129969.

Further reading

- Connor, Stephen (2010). "Side-stepping Geneva: Japanese Troops under British Control, 1945–7". Journal of Contemporary History. 45 (2): 389–405. doi:10.1177/0022009409356751. JSTOR 20753592. S2CID 154374567.

- Corbin, Alexander D. (2009). The History of Camp Tracy : Japanese WWII POWs and the Future of Strategic Interrogation. Fort Belvoir: Ziedon Press. ISBN 978-0578029795.

- Igarashi, Yoshikuni (2005). "Belated Homecomings: Japanese Prisoners of War in Siberia and their Return to Post-war Japan". In Moore, Bob; Hately-Broad, Barbara (eds.). Prisoners of War, Prisoners of Peace: Captivity, Homecoming, and Memory in World War II. New York: Berg. p. 105121. ISBN 1845201566.

- Sareen, T.R. (2006). Japanese Prisoners of War in India, 1942–46 : Bushido and Barbed Wire. Folkestone: Global Oriental Ltd. ISBN 978-1901903942.