| Chinese military texts |

|---|

The Jixiao Xinshu (simplified Chinese: 纪效新书; traditional Chinese: 紀效新書; pinyin: Jìxiào xīnshū) or New Treatise on Military Efficiency[1] is a military manual written during the 1560s and 1580s by the Ming dynasty general Qi Jiguang. Its primary significance is in advocating for a combined arms approach to warfare using five types of infantry and two type of support. Qi Jiguang separated infantry into five separate categories: firearms, swordsmen, archers with fire arrows, ordinary archers, and spearmen. He split support crews into horse archers and artillery units. The Jixiao Xinshu is also one of the earliest-existing East Asian texts to address the relevance of Chinese martial arts with respect to military training and warfare. Several contemporary martial arts styles of Qi's era are mentioned in the book, including the staff method of the Shaolin temple.

Background

In the late 16th century the military of the Ming dynasty was in poor condition. As the Mongol forces of Altan Khan raided the northern frontier, China's coastline fell prey to wokou pirates, who were ostensibly Japanese in origin. Qi Jiguang was assigned to the defense of Zhejiang in 1555, where he created his own standards of military organization, equipment, tactics, training, and procedures.[2] He published his thoughts on military techniques, tactics, and strategies in the Jixiao Xinshu after achieving several victories in battle.

Contents

There are two editions of the Jixiao Xinshu. The first edition was written from 1560-1561 and consists of 18 chapters. It is known as the 18-chapter edition. The second edition, published in 1584 during Qi's forced retirement, included re-edited and new material compiled in 14 chapters. It is known as the 14-chapter edition.

The chapters included in the 18-chapter edition are as follows:[3]

| Chapter | Subject |

|---|---|

| 1. | Five-man squads |

| 2. | Signals and commands |

| 3. | Motivating troops |

| 4. | Issuing orders; prohibitions during combat |

| 5. | Training officers |

| 6. | Evaluating soldiers; rewards and punishments |

| 7. and 8. | Field camp activities; in-camp drilling with flags and drums |

| 9. | The march |

| 10. | Use of polearms |

| 11. | Use of the shield |

| 12. | Use of swords |

| 13. | Archery |

| 14. | Quanjing Jieyao Pian (Chapter on the Fist Canon and the Essentials of Nimbleness); unarmed fighting |

| 15. | Devices and formations for defending city walls |

| 16. | Illustrations of standards, banners, and signal drums |

| 17. | Guarding outposts |

| 18. | Coastal warfare |

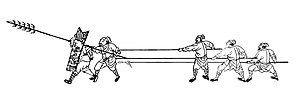

Mandarin duck formation

In the Jixiao Xinshu, Qi Jiguang recommended a 12-man team known as the "mandarin duck formation" (Chinese: 鴛鴦陣; pinyin: yuānyāng zhèn), which consisted of 11 soldiers and one person for logistics.[4]

- 4 men with long lances (twelve feet or longer) (chang qiang shou 長槍手)

- 2 men with sabers and rattan shields, one on each side of the lancers (dun pai shou 盾牌手)

- 2 men with multiple-tip spears (lang xian shou 狼筅手)

- 2 men with tridents or swords (duan bing shou 短兵手)

- 1 corporal (with the squad flag) (dui zhang 隊長)

- 1 cook/porter (logistical personnel) (fuze huoshi de huobing 負責夥食的火兵)

The mandarin duck formation was ideally symmetrical. Excluding the corporal and cook/porter, the ten remaining men could be split into two identical five-man squads. This was so that when Japanese pirates made it past the long lances, the saber-and-shield men formed a protective screen for the vulnerable lancers. In battle, the two saber-and-shield men had different roles. The one on the right would hold the advance position of the squad, while the one on the left was to throw javelins and lure the enemy closer. The two men with multiple-tip spears would entangle the pirates while the lancers attacked them. The trident carriers guarded the flanks and rear.[5]

Firearms

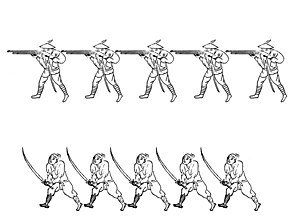

After suffering several defeats to pirates, Qi also made a recommendation for a concerted campaign to integrate musket teams into the army, based on their superior range and firepower compared to bows and arrows.[6] Qi became enamored with the musket after his defeats and became one of the primary proponents of their use in the Ming army. He favored it for its accuracy and its ability to penetrate armor.[6]

Ideally an entire musket team would have ten musketeers, but often had four or two in practice. The optimal musket formation that Qi proposed was a twelve-man musket team similar to the melee mandarin duck formation. However, instead of fighting in a hand to hand formation, they operated on the principle of volley fire, which Qi pioneered prior to the publication of the first edition of the Jixiao Xinshu.[6] The teams could be arranged in a single line, formed two layers deep with five musketeers each, or five layers deep with two muskets per layer. Once the enemy was within range, each layer would fire in succession, and afterwards a unit armed with traditional close combat weapons would move forward ahead of the musketeers. The troops would then enter into melee combat with the enemy together. Alternatively, the musketeers could be placed behind wooden stockades or other fortifications, firing and reloading continuously by turns.[7]

Once the enemy has approached to within 100-paces, listen for one's own commander (總) to fire once, and then each time a horn is blown the arquebusiers fire one layer. One after another, five horn tones, and five layers fire. Once this is done, listen for the tap of a drum, at which then one platoon (哨) [armed with traditional weapons] comes forward, proceeding to in front of the arquebusiers. They [the platoon members] then listen for a beat of the drum, and then the blowing of the swan-call horn, and they then give a war cry and go forth and give battle.[8]

— Jixiao Xinshu (18-chapter edition, 1560)

Each squad was drilled in coordinated and mutually supportive combat scenarios with clearly defined roles. Because Qi's troops were recruited from peasant stock, and were not considered the equals of their Japanese foes, Qi Jiguang emphasized the use of combined arms and squad tactics. Units were rewarded or punished collectively: an officer was executed if his entire unit fled the enemy, and if a squad leader was killed in battle, the whole squad would be put to death.[9]

Weapons production

The standard procedure for the procurement of weapons for a commander such as Qi Jiguang was for production quotas to be assigned by provincial officials to each local district under the commander's responsibility. The resulting weapons produced under this system varied widely in quality. Muskets in particular exploded with alarming frequency, leading Qi to eschew reliance on firearms in favor of using melee tools such as swords, rattan shields, and sharpened bamboo poles.[10] However, later in his career Qi became a strong proponent of integrating muskets after suffering several defeats to the pirates. Qi's reconsideration of firearms in warfare led to the creation of the first well-drilled musket teams in China. Qi was also a pioneer of the musket volley fire technique, which would later be adopted throughout China and Korea. Included in the manual are several passages detailing the usage of muskets, the volley fire technique, and an estimation of the percentage of firearms that would likely fail to fire.[11]

The manual provides the following description of the forging of swords:

The following steps in the manufacturing process of the short sword are necessary:

- The material of iron used must be forged many times (that is, heated, hammered and folded numerous times).

- The cutting edge must be made from the best steel, free of impurities.

- The entire part of the blade where the back or ridge of the blade joins the cutting edge must be filed so that they appear seamlessly joined together. This process is necessary to enable the sword to cut well.

Unarmed fighting

In Chapter 14 of the Jixiao Xinshu, this latter section known as the Quanjing Jieyao Pian, covers the subject of unarmed combat. Qi Jiguang regarded unarmed fighting as being useless on the battlefield. However, he recognized its value as a form of basic training to strengthen his troops, improving their physical fitness and confidence.[12]

In 32 verses, Qi describes several empty-hand ploys from among the martial arts of the period. The descriptions of the techniques are written in verse, typically with seven characters per line, three sections per verse.

These pithy descriptions rarely describe any technique in reproduceable detail. They allude to techniques rather obliquely, with a rough picture, with a follow up ploy or action, and often a boast.

While a hanfull of postures are illustrated, the tone of the verses implies that the reader should already be familiar with the techniques mentioned, or that Qi had little interest in actually divulging any empty hand fighting methods in his text.

Around 40 martial postures are identified in Qi's text by name. They are:

- Going Out the door posture

- Single whip stance

- Golden rooster stands on one leg

- Reclined ox stance

- spy technique

- short strike

- Yellow flower close in tightly

- push to upend Mt.Tai

- Aloes wood posture

- Seven star strike

- Mount the dragon backwards

- lower jabbing position

- Ambush crouch posture

- Elbow in hand position

- splitting strike and pushing press

- One instant step

- Capture and grab stance

- middle four level position

- Crouched tiger posture

- upper four level position

- Reverse stabbing position

- Back-facing bow stance

- Well railing four-wise balanced

- rapid boring split

- Ghost kicking foot

- fall recovery

- elbow that bores the heart

- Finger opposition posture

- Beast head position

- Spirit fist

- Grounded sparrow beneath the dragon

- Sun-facing hand

- Knockdown posture

- Wild goose wings stance

- clipping split

- Straddling tiger posture

- Loose hands scissor maneuver

- Eagle seizes the rabbit position

- Canonball against the head maneuver

- Shuan shouh strike

- Banner and drum posture

Some of these techniques are preserved in modern martial arts. 15 techniques have extremely similar or exact names to those in modern-day Taijiquan, especially Chen Style. They are:

- Going Out the Door position [aka Block Brushing Clothes, or Casually Fixing Clothes]

- Single Whip stance

- Golden Rooster stands on one leg

- Spy technique [Seek the Spy/Measure the Horse]

- Push and upend Mt. Tai [Cover Head Push Mountain]

- Seven Star strike

- Mount the dragon backwards [Mount The Donkey Backwards]

- Elbow in hand position [Fist Under Elbow]

- Capture and Grab stance [Small Catch & Grab]

- Red fist

- Elbow that bores the heart

- Beast Head position

- Wild Goose Wings stance [White Goose (or Crane) Spreads Wings]

- Straddling Tiger posture

- Canonball Against the Head maneuver

Techniques: Cannon Towards Head, Goose Spreads Wings; are described in enough detail to be recognized as almost exactly the same to this day. Others such as Single Whip, Golden Rooster, Push Mountain, Seven Star Stance, Red Fist, Beast Head Pose, are staples of several northern Chinese martial arts in general.

Some theorize that modern Taijiquan started as the gambits described in the 32 Empty hand verses of Qi Jiguang being taken by Chen Wangting as the basis for his supposedly new art. There does seem to be notable overlap, but the number of named techniques covers only a fraction of the techniques even in early lists of Taijiquan routines, much less the latter ones. It is just as likely many techniques were simply widespread in that era.

In the chapter's introduction, Qi names sixteen different fighting styles, all of which he considered to have been handed down in an incomplete fashion, "some missing the lower part, some missing the upper".[13]

Among the arts listed is the Shaolin staff method, which was later documented in detail in Cheng Zongyou's Exposition of the Original Shaolin Staff Method, published around 1610.[14] By contrast, Shaolin unarmed fighting techniques are not mentioned.

The entire listing of late Ming dynasty martial arts was later copied without attribution by a manual of the Shaolin style, the Hand Combat Classic (Quanjing quanfa beiyao). However, the later manual, with a preface dated to 1784, altered the text, adding a spurious claim that the history of hand combat had originated at the Shaolin Monastery.[15]

Qi's discussion of hand-to-hand combat makes no mention of a spiritual element to the martial arts, nor does it allude to breathing or qi circulation. By contrast, Chinese martial arts texts from the Ming–Qing transition onward represent a synthesis of functional martial arts techniques with Daoist daoyin health practices, breathing exercises, and meditation.[16][17]

Influence

Qi Jiguang was one of several Ming authors to document the military tactics and martial arts techniques of the era. The earliest known documentation of specific styles of Chinese martial arts were produced during the late Ming piracy crisis, as scholars and generals such as Qi and his contemporary Yu Dayou turned their attention to reversing the decline of the Ming military. In the late 16th century, the Japanese invasions of Korea also spurred great interest in military training methods within the Korean government. Qi Jiguang's writings were of particular interest because of his successful campaigns against Japanese pirates several decades prior. The 14-chapter edition of the Jixiao Xinshu served as a model for the oldest-known extant Korean military manual, the Muyejebo, and was disseminated among Korean military thinkers.

In Japan both the 14- and 18-chapter editions were published several times, and some methods from the Jixiao Xinshu were transferred over to the Heiho Hidensho (Okugisho), a Japanese strategy book written by Yamamoto Kansuke in the 16th century.

Gallery

-

Layout of the 'mandarin duck formation'

-

The 'second power formation' is a split 'mandarin duck squad'

-

The 'lesser third power formation'

-

The 'third power formation'

-

The army prepares for combat and deploys in battle lines.

-

A fortified camp formation from the Jixiao Xinshu

See also

- Wujing Zongyao – Chinese military compendium written from around 1040 to 1044

- Huolongjing – mid-14th-century Chinese military treatise

- Wubei Zhi – Chinese military book compiled in 1621

References

- ^ Shahar 2008, p. 62

- ^ Huang 1981, p. 159

- ^ Gyves 1993, pp. 16–18

- ^ Huang 1981, p. 168

- ^ Huang 1981, pp. 168–169

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 172.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 174.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 173.

- ^ Huang 1981, pp. 167–169

- ^ Huang 1981, pp. 170–171

- ^ Huang 1981, p. 172

- ^ Gyves 1993, p. 33

- ^ Gyves 1993, pp. 34–35

- ^ Shahar 2008, pp. 56–57

- ^ Shahar 2008, pp. 116–117

- ^ Shahar 2008, pp. 148–149

- ^ Lorge 2011, p. 202

Bibliography

- Gyves, Clifford M. (1993), An English Translation of General Qi Jiguang's "Quanjing Jieyao Pian" (PDF), University of Arizona, archived (PDF) from the original on November 9, 2013

- Qi, Ji Guang 紀效新書·卷首~卷六 Military Effectiveness New Treatise (18 Chapter) 01-06, Archive.org (185p)

- Qi, Ji Guang 紀效新書·卷七~卷十 Military Effectiveness New Treatise (18 Chapter) 07-10, Archive.org (172p)

- Qi, Ji Guang 紀效新書·卷十一~卷十四 Military Effectiveness New Treatise (18 Chapter) 11-14, Archive.org (134p)

- Qi, Ji Guang 紀效新書·卷十五~卷十七 Military Effectiveness New Treatise (18 Chapter) 15-17, Archive.org (189p)

- Qi, Ji Guang 紀效新書·卷十八 Military Effectiveness New Treatise (18 Chapter) 18, Archive.org (107p)

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Huang, Ray (1981), 1587, a Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-02518-7

- Lorge, Peter A. (2011), Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-87881-4

- Shahar, Meir (2008), The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-3349-7