John of Brittany | |

|---|---|

| Earl of Richmond | |

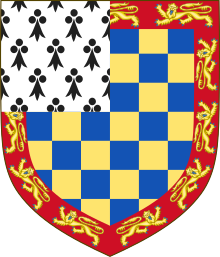

Arms of John of Brittany | |

| Tenure | 1306–1334 |

| Predecessor | John II, Duke of Brittany |

| Successor | John III, Duke of Brittany |

| Other titles | Count of Treguier |

| Other names | Jean de Bretagne |

| Years active | 1294–1327[1] |

| Born | c. 1266 |

| Died | 17 January 1334 Duchy of Brittany |

| Buried | Church of the Franciscans, Nantes |

| Nationality | English, French, Breton[a] |

| Locality | Yorkshire[2] |

| Wars and battles | First War of Scottish Independence • Battle of Falkirk (1298) • Siege of Caerlaverock (1300) • Battle of Old Byland (1322) (POW) |

| Offices | Guardian of Scotland Lord Ordainer |

| Parents | John II, Duke of Brittany Beatrice of England |

John of Brittany (French: Jean de Bretagne; c. 1266 – 17 January 1334), 4th Earl of Richmond, was an English nobleman and a member of the Ducal house of Brittany, the House of Dreux. He entered royal service in England under his uncle Edward I, and also served Edward II. On 15 October 1306 he received his father's title of Earl of Richmond.[3] He was named Guardian of Scotland in the midst of England's conflicts with Scotland and in 1311 Lord Ordainer during the baronial rebellion against Edward II.

John of Brittany served England as a soldier and as a diplomat but was otherwise politically inactive in comparison to other earls of his time.[b] He was a capable diplomat, valued by both Edward I and Edward II for his negotiating skills. John was never married, and upon his death his title and estates fell to his nephew, John III, Duke of Brittany. Although he was generally loyal to his first cousin Edward II during the times of baronial rebellion, he eventually supported the coup of Isabella and Mortimer. After Edward II abdicated in favour of his son Edward III of England, John retired to his estates in France and died in his native Brittany in 1334 with no known issue.

Early life

John was the second surviving son of John II, Duke of Brittany, and his wife Beatrice, who together had three sons and three daughters who survived to adulthood. Beatrice was the daughter of Henry III of England, which made John the nephew of Henry's son and heir Edward I.[5] His father held the title of Earl of Richmond, but was little involved in English political affairs.[6] John was raised at the English court together with Edward I's son Henry, who died in 1274.[7] He participated in tournaments in his youth, but never distinguished himself in his early roles as a soldier.[1]

Service to Edward I

When in 1294 the French king confiscated King Edward's Duchy of Aquitaine, John travelled to France[8] as the lieutenant of the Duchy,[9] but failed to take Bordeaux. During Easter of 1295 he had to flee the town of Rions.[10] In January 1297 he shared defeat at the Siege of Bellegarde with Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. After this defeat, he returned to England.[11]

Despite his poor results in France he remained highly regarded by his uncle King Edward I, who treated him almost as a son.[12] After his return to England John became involved in the Scottish Wars. He was probably at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298. He was certainly at the Siege of Caerlaverock in 1300.[11] The nobles who joined Edward I at the Siege of Caerlaverock, including John of Brittany, were commemorated in the Roll of Caerlaverock which named each noble and described their banner.[c][d] In this roll, the banner and description of John of Brittany immediately follows that of his uncle King Edward I.[e]

His father, the Duke of Brittany, died in 1305, and was succeeded as duke by John's elder brother, Arthur. The following year Edward I invested John with his father's other title, Earl of Richmond.[13] In addition Edward I appointed him Guardian of Scotland, a position which was confirmed upon the accession of Edward II in 1307.[1]

Service to Edward II

The English court viewed John of Brittany as a trusted diplomat.[1] He was a skilled negotiator, and his French connections were a useful asset.[14] By 1307 he was also one of the kingdom's oldest earls.[15] As the relationship between Edward II and his nobility deteriorated, Richmond remained loyal to the king; in 1309 he went on an embassy to Pope Clement V on behalf of Edward's favourite Piers Gaveston.[16] John was allegedly Gaveston's close personal friend, and did not share the antagonistic attitudes held by certain other earls.[17]

Lord Ordainers

By 1310 the relationship between Edward II and his earls had deteriorated to the point where a committee of earls took control of government from the king. The earls disobeyed a royal order not to carry arms to parliament, and in full military attire presented a demand to the king for the appointment of a commission of reform. At the heart of the deteriorating situation was the peers' opinion of Edward II's relationship with Piers Gaveston, and his reputedly outrageous behaviour. On 16 March 1310, the king agreed to the appointment of Ordainers, who were to be in charge of the reform of the royal household.[18] John of Brittany was one of eight earls appointed to this committee of 21, referred to as the Lords Ordainers.[19] He was among the Ordainers considered loyal to Edward II and was also by this time one of the older remaining earls.

John then travelled to France for diplomatic negotiations, before returning to England. Gaveston was exiled by the Ordainers but later made an irregular return. Gaveston was killed in June 1312 by Thomas of Lancaster and other nobles.[20] It fell upon John, together with Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, to reconcile the two parties after this event.[21] In 1313 he followed Edward II on a state visit to France, and thereafter generally remained a trusted subject. In 1318 he witnessed the Treaty of Leake, which restored Edward to full power.[22]

War with Scotland

In 1320 he again accompanied Edward II to France, and the next year he carried out peace negotiations with the Scots.[23] When in 1322 Thomas of Lancaster rebelled and was defeated at the Battle of Boroughbridge, Richmond was present at his trial, and when Lancaster was sentenced to death.[24] After this, the English invaded Scotland only to have their army starved when Robert the Bruce burned the country before them. The Bruce brought his army into England and crossed the Solway Firth in the west, making his way in a south-easterly direction towards Yorkshire; he brought many troops recruited in Argyll and the Isles. The boldness and speed of the attack soon exposed Edward II to danger, even in his own land. On his return from Scotland, the king had taken up residence at Rievaulx Abbey with Queen Isabella. His peace was interrupted when the Scots made a sudden and unexpected approach in mid-October. All that stood between them and a royal prize was a large English force under the command of John of Brittany. John had taken up a position on Scawton Moor, between Rievaulx and Byland Abbey. To dislodge John from his strong position on the high ground, Bruce used the same tactics that brought victory at the earlier Battle of the Pass of Brander. As Moray and Douglas charged uphill a party of Highlanders scaled the cliffs on the English flanks and charged downhill into John of Brittany's rearguard. Resistance crumbled, and the Battle of Old Byland turned into a rout. John himself was taken prisoner and given a tongue lashing by King Robert the Bruce for his treatment of the Scottish Queen while she was an English prisoner.[25][f][26] John remained in captivity until 1324, when he was released for a ransom of 14,000 marks.[1]

After his release, he continued his diplomatic activities in Scotland and France.

Final years

In March 1325 John of Brittany made a final return to France, where for the first time he made himself a clear opponent of Edward II. His lands in England were confiscated by the Crown.[1] In France, John aligned himself with Queen Isabella, Edward II's wife, who had been sent on a diplomatic mission to France, and had disobeyed her husband's orders to return to England.[27][g] Later when Edward II was forced to abdicate and his son Edward III ascended to the English throne, John of Brittany's English lands were restored. He spent his last years on his French estates, and he remained largely cut off from English political affairs. He died on 17 January 1334, and was buried in the church of the Franciscans in Nantes.[1][11][h]

John of Brittany never married and as far as is known had no issue. He was succeeded as Earl of Richmond by his nephew John (Arthur's son).[3]

Notes

- ^ During his lifetime, the Duchy of Brittany remained independent of both the Kingdoms of England and France, and maintained relations with both the English and French courts. His particular career is indicative of that of a medieval Breton noble who was active in England during the period of the Norman Conquest following the Battle of Hastings in 1066, but ended his life's work in his home territory of the Duchy of Brittany. See place of retirement and interment as Nantes.

- ^ John of Brittany was not an accomplished soldier, and among the earls of England he was politically quite insignificant.[4]

- ^ The Roll states: " Son nevou Johan de Bretaigne, Por ce ke plus esr de li près, Soi je plus tost nomer après. Si le avoit-il ben deservi, Cum cil ki son oncle ot servi, De se enfance peniblement, E deguerpi outréement Son pere e son autre lignage, Por demourer de son maisnage, Kant li Rois ot bosoign de gens, Baniere avoit cointe e parée, De or e de asur eschequeré, A rouge ourle o jaunes lupars, De ermine estoit la quart pars.""

- ^ [The King's nephew] John of Brittany remained close to the king and so is named after him. He acted in a much deserving way and from childhood lived apart from his father and his paternal line to live with the King in his household. When the King needed help [Earl John's] banner appeared.[The banner is described: bordered in red with yellow leopards, and hermine in one quarter].

- ^ The close placement next to the King is consistent with John's membership in the King's household and their close relationship. It would not be surprising as a confirmation that when the King was present on the field of battle, John remained close to him for various reasons.

- ^ Edward II escaped the battle leaving behind his treasury including the Great Seal.

- ^ In September 1326 Isabella, her lover Mortimer, and a small army, invaded England. By January 1327 Edward II had been forced to abdicate, and his son was declared King Edward III.[28]

- ^ This is believed to be Notre Dame in Nantes. Many early Breton nobles were buried throughout Nantes.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Jones 2004.

- ^ Given-Wilson 1996, p. 186.

- ^ a b Fryde 1961, p. 446.

- ^ Phillips 1972, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Phillips 1972, p. 16.

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 235.

- ^ Johnstone 1923.

- ^ Prestwich 1997, pp. 378–9.

- ^ "Principal Office Holders in the Duchy" and "King's Lieutenants in the Duchy (1278–1453)", The Gascon Rolls Project (1317–1468).

- ^ Prestwich 1997, pp. 381–2.

- ^ a b c Cokayne 1910–59.

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 132.

- ^ Prestwich 2007, p. 361.

- ^ Phillips 1972, p. 271.

- ^ McKisack 1959, p. 1.

- ^ Hamilton 1988, p. 69.

- ^ Hamilton 1988, pp. 56, 67.

- ^ McKisack 1959, p. 10.

- ^ Prestwich 2007, p. 182.

- ^ Chaplais 1994, p. 88.

- ^ Phillips 1972, pp. 42–4.

- ^ Phillips 1972, p. 172.

- ^ Phillips 1972, pp. 192, 204.

- ^ Maddicott 1970, pp. 311–2.

- ^ Scott, Ronald McNair (1988). Robert the Bruce, King of Scots. New York: Peter Bedrick Books. p. 204.

- ^ Barrow 1965, p. 317.

- ^ McKisack 1959, p. 82.

- ^ McKisack 1959, pp. 83–91.

Sources

- Barrow, G. W. S. (1965). Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. ISBN 9780748620227.

- Chaplais, P. (1994). Piers Gaveston: Edward II's Adoptive Brother. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-820449-3.

- Cokayne, George (1910–59). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom. Vol. x (New ed.). London: The St. Catherine Press. pp. 814–8.

- Fryde, E. B. (1961). Handbook of British Chronology (Second ed.). London: Royal Historical Society. p. 446.

- Given-Wilson, Chris (1996). The English Nobility in the Late Middle Ages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14883-9.

- Hamilton, J. S. (1988). Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall, 1307–1312: Politics and Patronage in the Reign of Edward II. Detroit; London: Wayne State University Press; Harvester-Wheatsheaf. ISBN 0-8143-2008-2.

- Johnstone, Hilda (1923). "The wardrobe and household of Henry, son of Edward I". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 7 (3): 384–420. doi:10.7227/BJRL.7.3.4.

- Jones, Michael (2004). "Brittany, John of, earl of Richmond (1266?–1334)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/53083.

- McKisack, May (1959). The Fourteenth Century: 1307–1399. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821712-9.

- Maddicott, J.R. (1970). Thomas of Lancaster, 1307–1322. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821837-0. OCLC 132766.

- Phillips, J.R.S. (1972). Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke 1307–1324. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822359-5. OCLC 426691.

- Prestwich, Michael (1997). Edward I (updated ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07209-0.

- Prestwich, Michael (2007). Plantagenet England: 1225–1360 (new ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822844-8.

- Roll of Caerlaverock.

Further reading

- Lobineau, G.A. (1707). Histoire de Bretagne (in French).

- Liubimenko, Inna Ivanovna (1908). Jean de Bretagne comte de Richmond Sa vie et son activité en Angleterre en Écosse et en France (1266–1334) (in French). Lille.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)