Katherine Mary Clerk Maxwell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Katherine Mary Dewar 1824 Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Scotland |

| Died | 12 December 1886 (aged 61–62) Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England |

| Resting place | Parton, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland |

| Known for | Research supporting experiments of James Clerk Maxwell |

| Spouse |

James Clerk Maxwell

(m. 1858; died 1879) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physical sciences |

Katherine Mary Clerk Maxwell (née Dewar; 1824 – 12 December 1886) was the wife of Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell. She aided him in some of his work on colour vision and his experiments on the viscosity of gases. She was born Katherine Dewar in 1824 in Glasgow[1][2] and married Clerk Maxwell in Aberdeen in 1858.[3][4]

Early life and marriage

Katherine Mary Dewar was born in 1824 in Glasgow,[1][2] the daughter of Susan Place[1] and the Presbyterian Rev. Daniel Dewar,[5] later Principal of Marischal College, Aberdeen.[3] Few details of her early life appear to have been recorded.

When she was in her early 30s she met James Clerk Maxwell (seven years her junior) while he was Professor of Natural Philosophy at Marischal College (1856–1860).[1] Maxwell and her father, Rev. Daniel Dewar, developed a friendship which resulted in Maxwell frequently visiting the Dewar household and joining the Dewars on a family holiday.[6] James announced their engagement in February 1858[7] and they were married in the parish of Old Machar, Aberdeen, on 2 June 1858.[3][4] The couple did not have children.

Scientific contribution

Before and during their marriage Katherine aided James in some of his experiments on colour vision and gases.[1][7] In his paper "On the Theory of Compound Colours, and the Relations of the Colours of the Spectrum", published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1860, James recorded the observations of two individuals. He reveals himself as the first observer, labeled J, but describes the second individual anonymously as "another observer (K)."[8] Lewis Campbell confirms that the observer K was indeed Katherine.[7]

Colour vision experiments

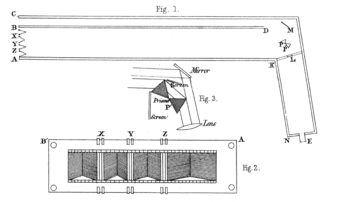

The apparatus used in the colour vision experiments is depicted in Fig. 1. It was constructed by joining a box of 5 feet (1.5 m) (AK) with a box of 2 feet (0.61 m) (KN) at a 100-degree angle. A mirror at M reflects light coming through the opening at BC towards a lens at L. Two equilateral prisms at P refract light coming from the three slits at X, Y, and Z. This illuminated the prisms with the combination of the spectral colours created by the diffraction of the light from the slits. This light was also visible through the lens at L. The observer then peered through the slit at E while the operator adjusted the position and width of each slit at X, Y, and Z until the observer could not distinguish the prism light from the pure white light reflected by the mirror. The position and width of each slit was then recorded.

James and Katherine performed this experiment in their home in London. Their neighbours reportedly thought that they were "mad to spend so many hours staring into a coffin."[7] Katherine's observations differed from James's on several accounts. James described these differences in section XIII of his publication, noting that there was a "measurable difference" between the colours perceived by each observer.[8] Campbell also cites readings by Maxwell's cousin Charles Hope Cay to be different from Katherine's, although a third observer is not listed in this particular Philosophical Transactions publication.[7] This led Maxwell to develop his theory of colour vision and to discover the commonly occurring blindness of the Foramen Centrale to blue light.

Viscosity of gas experiments

In a letter to P.G. Tait, James Clerk Maxwell wrote about Katherine's contribution to measurements of gaseous viscosity associated with his paper "On the Dynamical Theory of Gases", saying that Katherine "did all the real work of the kinetic theory" and that she was now "...engaged in other researches. When she is done I will let you know her answer to your inquiry [about experimental data]".[1][9] Katherine's main work for these experiments involved keeping a fire continuously stoked for hours on end in order to produce steam from a kettle and so maintain a constant temperature for the gases whose viscosity Maxwell was measuring.[7]

Personal life

After the merger of Marischal College with Kings College to form the new University of Aberdeen in 1860, Maxwell lost his position and the couple moved to London for five years, where Maxwell served as professor of Natural Philosophy at King's College. Katherine nursed her husband through smallpox in September 1860 at the Maxwell family estate in Scotland, then through erysipelas following a riding incident in September 1865.[7] The Maxwells were avid riders. In a letter to a friend and colleague, James mentioned their regular outings to the Brig of Urr, mounted on their horses Darling and Charlie.[7] Charlie was a bay pony that James bought for Katherine at a horse fair where James allegedly contracted smallpox.[6] Charlie was named after Charles Hope Cay, the cousin to whom James wrote.

The couple moved to the Maxwell estate, Glenlair, in 1865, with James using this time to write up some of his key work.[7] In 1871 James Clerk Maxwell was appointed Cambridge University's first Cavendish Professor of Experimental Physics.[4] During this time the couple lived in Cambridge but continued to spend summers at Glenlair.[2]

Katherine had a number of health issues[7] and suffered a prolonged illness in 1876, which her husband nursed her through.[10] Despite this, and Katherine's role in caring for her husband, Margaret Tait (wife of P. G. Tait) is said to have accused Katherine of derailing her husband's career because of her illness and James Clerk Maxwell's care for her.[1]

Katherine was widowed when James Clerk Maxwell died of stomach cancer in Cambridge on 5 November 1879.[7] On the day of his death James expressed concern for Katherine's health.[7] Katherine continued to live in their house on Scroope Terrace in Cambridge, but little else is known of her life during the seven years between her husband's death and her own.[1]

She died in Cambridge on 12 December 1886 and is buried alongside her husband in Parton, Dumfries and Galloway.[11]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lightman, Bernard (2004). The Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century British Scientists: Volume 3: K-Q. Bristol, UK: Thoemmes Continuum. pp. 1381–2. ISBN 978-1855069992.

- ^ a b c Flood, Raymond; McCartney, Mark; Whitaker, Andrew (9 January 2014). James Clerk Maxwell: Perspectives on his Life and Work. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191641251.

- ^ a b c O'Conner, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. "James Clerk Maxwell (biography)". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. School of Mathematics and Statistics University of St Andrews, Scotland. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ a b c "Facts about James Clerk Maxwell". James Clerk Maxwell Foundation. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ Lundy, Darryl. "Katherine Mary Dewar". The Peerage. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ a b Basil., Mahon (1 January 2003). The man who changed everything : the life of James Clerk Maxwell. Wiley. OCLC 52358254.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Campbell, Lewis; Garnett, William (3 June 2010). The Life of James Clerk Maxwell: With a Selection from His Correspondence and Occasional Writings and a Sketch of His Contributions to Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108013703.

- ^ a b Maxwell, J. Clerk (1860). "On the Theory of Compound Colours, and the Relations of the Colours of the Spectrum". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 150: 57–84. doi:10.1098/rstl.1860.0005.

- ^ Clerk Maxwell, James (1877). Letter to P.G. Tait. Maxwell Papers, Cambridge University Library.

my better 1/2, who did all the real work of the kinetic theory is at present engaged in other researches. When she is done I will let you know her answer to your enquiry [about experimental data]

- ^ Everitt, C. W. F. (1975). James Clerk Maxwel: Physicist and Natural Philosopher. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "James Clerk Maxwell's burial place at Parton". www.clerkmaxwellfoundation.org. James Clerk Maxwell Foundation. Retrieved 31 October 2016.