Kingdom of the Aurès Regnum Aurasium | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 484–703 | |||||||||

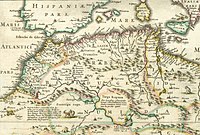

The approximate extent of the Kingdom of the Aurès around the time of the collapse of the Vandal Kingdom | |||||||||

| Capital | Arris (400s – 500s) Khenchela (600s – 700s)a | ||||||||

| Common languages | Berber, African Romance | ||||||||

| Religion | Christianity | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• c. 484 – c. 516 | Masties | ||||||||

• c. 516 – 539 | Iabdas | ||||||||

• 668–703 | Dihya | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Separation from the Western Roman Empire | 429 | ||||||||

• Death of the vandal king Huneric | 484 | ||||||||

| 703 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Algeria | ||||||||

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

The Kingdom of the Aurès (Latin: Regnum Aurasium) was an independent Christian Berber kingdom primarily located in the Aurès Mountains of present-day north-eastern Algeria.[1] Established in the 480s by King Masties following a series of Berber revolts against the Vandalic Kingdom, which had conquered the Roman province of Africa in 435 AD, Aurès would last as an independent realm until the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb in 703 AD when its last monarch, Queen Dihya, was slain in battle.

Much like the larger Mauro-Roman Kingdom, the Kingdom of the Aurès combined aspects of Roman and Berber culture in order to efficiently rule over a population composed of both Roman provincials and Berber tribespeople. For instance, King Masties used the title of Dux and later Imperator to legitimize his rule and openly declared himself a Christian. Despite this, Aurès would not recognize the suzerainty of the remaining Roman Empire in the East (often called the Byzantine Empire by modern historians) and King Iabdas unsuccessfully invaded the Praetorian prefecture of Africa, established after the Byzantines had defeated the Vandals. One possible reason towards why the Berbers could not be integrated as successfully into the Byzantine Empire as they had been before was the Byzantine shift in language from Latin to Greek, the Berbers were thus no longer bilingual with the language of their nominal rulers.

Despite these hostilities, the Byzantines supported Aurès during the Muslim invasion of the Maghreb, hoping that the kingdom could act as a resistance to the Arabs. The final Queen of the kingdom, Dihya, was the final leader of the Berber resistance against the Arabs, which ended with her death and the fall of the Kingdom of the Aurès in 703 AD.

History

Establishment

According to the Eastern Roman historian Procopius, the Moors only began to truly expand and consolidate their power following the death of the powerful vandal king Gaiseric in 477 AD, after which they won many victories against the Vandal kingdom and established more or less full control over the former province of Mauretania. Having feared Gaiseric, the Moors under Vandal control revolted against his successor Huneric following his attempt to convert them to Arian Christianity and the harsh punishments incurred on those who did not convert. In the Aurès Mountains, this led to the foundation of the independent Kingdom of the Aurès, which was fully independent by the time of Huneric's death in 484 AD and would never again come under Vandal rule. Under the rule of Huneric's successors Gunthamund and Thrasamund, the wars between the Berbers and the Vandals continued. During Thrasamund's reign, the Vandals suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of a Berber king ruling the city Tripolis, named Cabaon, who almost completely destroyed a Vandal army that had been sent to subjugate the city.[2]

As the new Berber kingdoms adopted the military, religious and sociocultural organization of the Roman Empire, they continued to be fully within the Western Latin world. The administrative structure and titulature used by the Berber rulers suggests a certain romanized political identity in the region.[3] This Roman political identity was maintained not only in the large Mauro-Roman Kingdom but in smaller kingdoms, such as the Kingdom of the Aurès, where King Masties claimed the title of Imperator during his rule around 516 AD, postulating that he had not broken trust with either his Berber or Roman subjects.[4]

Masties had established a realm in Numidia and the Aurés Mountains, with the Arris as his own residence, and used Imperator to legitimize his rule over the Roman provincials, also openly declaring himself a Christian during his rebellion against Huneric. According to his own 516 AD inscription, Masties had reigned for 67 years as a dux, and 10 years as Imperator up until that point.[5][6]

The Vandalic War and its aftermath

Byzantine records referring to the Vandal Kingdom, which had occupied much of the old Roman province of Africa and coastal parts of Mauretania, often refer to it with regards to a trinity of peoples; Vandals, Alans and Moors, and though some Berbers had assisted the Vandals in their conquests in Africa, Berber expansion was more often than not focused against the Vandals rather than with them, which would lead to some expansion of even the smaller local kingdoms, such as the Aurès.[7]

Following the Byzantine re-conquest of the Vandal Kingdom, the local governors began to experience problems with the local Berber tribes. The province of Byzacena was invaded and the local garrison, including the commanders Gainas and Rufinus, was defeated. The newly appointed Praetorian prefect of Africa, Solomon, waged several wars against these Berber tribes, leading an army of around 18,000 men into Byzacena. Solomon would defeat them and return to Carthage, though the Berbers would again rise and overrun Byzacena. Solomon would once again defeat them, this time decisively, scattering the Berber forces. Surviving Berber soldiers retreated into Numidia where they joined forces with Iabdas, King of the Aurès.[8][9] Masuna, King of the Mauro-Roman Kingdom and allied with the Byzantines, and another Berber king, Ortaias (who ruled a kingdom in the former province of Mauretania Sitifensis),[10] urged Solomon to pursue the enemy Berbers into Numidia, which he did. Solomon did not engage Iabdas in battle however, distrusting the loyalty of his allies, and instead constructed a series of fortified posts along the roads linking Byzacena with Numidia.[9][11]

Though the Roman Empire had once exercised control over the Berbers and the Berbers continued to nominally respect Roman authority during Byzantine rule over North Africa, they could not be as easily integrated as before partly due to the Byzantine shift in language from Latin to Greek, the Berbers were no longer bilingual with the language of their nominal rulers.[12]

Wars against the Arabs

Despite previous hostilities, the Byzantine Empire supported the Kingdom of the Aurès during the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb, hoping that the kingdom would act as resistance to the Arabs.[12] Even with the fall of the Mauro-Roman kingdom in the 570s, its capital of Altava appears to have somewhat remained a seat of Berber power. The Altavan king Kusaila, the last Berber king to rule from Altava, died fighting against the Umayyad Caliphate. At the Battle of Mamma in 690 AD, a combined Byzantine-Altavan army was defeated and Kusaila was killed.[13]

With the death of Kusaila, the torch of resistance passed to a tribe known as the Jerawa tribe, who had their home in the Aurès Mountains: his Christian Berber troops after his death fought later under Dihya, the queen of the Kingdom of the Aurès and the last ruler of the romanized Berbers.[13] Dihya led the Berber resistance against the Arabs but was killed in battle in 703 AD near a well that still bears her name, Bir al Kahina ("Kahina" coming from al-Kāhina, her nickname in Arabic), in Aures.[14]

List of known kings and queens of the Aurès

| Monarch | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Masties | c. 484 – c. 516 | Founded the kingdom following a revolt against the Vandal king Huneric. Claimed the title Imperator.[5][6] |

| Iabdas | c. 516 – 539 | Led a short-lived conflict against the newly re-conquered Byzantine North Africa.[8][9] Fled to Mauretania following his defeat at the hands of the Byzantines in 539 AD.[15] |

| Dihya | c. 668 – 703 | Ruling Queen. The final ruler of Aurès and the romanized Berbers. Said to have ruled for 35 years, ruler of the entire Berber resistance from 690 AD onwards.[13] |

References

Citations

- ^ Austin Markus, Robert (2009). From Augustine to Gregory the Great: History and Christianity in Late Antiquity. Variorum Reprints. p. 11-12. ISBN 9780860781172.

- ^ Procopius.

- ^ Conant 2012, p. 280.

- ^ Rousseau 2012.

- ^ a b Merrills & Miles 2009, pp. 127–128.

- ^ a b Modéran 2003.

- ^ Wolfram 2005, p. 170.

- ^ a b Martindale 1992, p. 1171.

- ^ a b c Bury 1958, p. 143.

- ^ Grierson 1959, p. 126.

- ^ Martindale 1992, p. 1172.

- ^ a b Rubin 2015, p. 555.

- ^ a b c Talbi 1971, pp. 19–52.

- ^ Julien & Le Tourneau 1970, p. 13.

- ^ Raven 2012, pp. 213–219.

Sources

- Bury, John Bagnell (1958). History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian, Volume 2. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20399-9.

- Conant, Jonathan (2004). Literacy and Private Documentation in Vandal North Africa: The Case of the Albertini Tablets within Merrills, Andrew (2004) Vandals, Romans and Berbers: New Perspectives on Late Antique North Africa. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-4145-7.

- Conant, Jonathan (2012). Staying Roman: Conquest and Identity in Africa and the Mediterranean, 439–700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107530720.

- Grierson, Philip (1959). "Matasuntha or Mastinas: a reattribution". The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. 19: 119–130. JSTOR 42662366.

- Julien, Charles André; Le Tourneau, Roger (1970). Histoire de L'Afrique du Nord (in French). Praeger. ISBN 9780710066145.

- Martindale, John Robert (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume 3, AD 527–641. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521201599.

- Merrills, Andrew; Miles, Richard (2009). The Vandals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1405160681.

- Modéran, Yves (2003). Les Maures and l'Afrique romaine. 4e.–7e. siècle (= Bibliothèque des écoles françaises d'Athènes et de Rome, vol. 314) (in French). Rome: Publications de l'École française de Rome. ISBN 2-7283-0640-0.

- Procopius (545). "Book III–IV: The Vandalic War (pts. 1 & 2)". History of the Wars.

- Raven, Susan (2012). Rome in Africa. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415081504.

- Rousseau, Philip (2012). A Companion to Late Antiquity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-405-11980-1.

- Rubin, Barry (2015). The Middle East: A Guide to Politics, Economics, Society and Culture. Routledge. ISBN 978-0765680945.

- Talbi, Mohammed (1971). Un nouveau fragment de l'histoire de l'Occident musulman (62–196/682–812): l'épopée d'al Kahina (in French). Cahiers de Tunisie vol. 19. pp. 19–52.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wolfram, Herwig (2005). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520244900.