The Maharaj Libel Case was an 1862 trial in the Bombay High Court in the Bombay Presidency, British India. The case was filed by Jadunathjee Brajratanjee Maharaj, against Nanabhai Rustomji Ranina and Karsandas Mulji. The case was filed because of an editorial article published by them accusing the Vallabhacharya and Pushtimarg Sect of certain alleged controversial practices that had been followed by the leaders. This case highlighted conflicts between traditional yet controversial social practices such as charan seva amidst emerging reformist ideas in colonial India, garnering significant public attention and praise for Mulji's efforts.[1][2][3][4]

Background

The case arose when the plaintiff, Jadunathjee Brajratanjee Maharaj, a religious leader, filed a case of libel against a reformer and journalist Karsandas Mulji for writing an article in the newspaper, Satyaprakash, titled Hinduo No Asli Dharam Ane Atyar Na Pakhandi Mato (lit. 'The True/Original Religion of the Hindus and the Present Hypocritical/phoney Sects'). In this article he questioned the values of a Hindu sect called the Pushtimarg or Vallabha Sampradaya. The article was claimed to be libelous by the plaintiff. In particular were accusations that Jadunathjee had sexual liaisons with women followers and that men were expected to show their devotion by offering their female family members for sex with the religious leaders.[5][6]

Jadunathjee was a religious leader of the Vaishnavite Pushtimarg sect of Hinduism. The sect was founded in the 16th century by Vallabha and worships Krishna as the supreme being. The leadership of the sect remained with Vallabha's direct male descendants who possess the titles of maharaja. Theologically Vallabha and his descendants are accorded partial divinity as mediating figures for Krishna's grace who are able to render Krishna's presence immediately to the devotee.[7][8]

Pushtimarg's followers in Gujarat, Kathiyawad, Kutch, and central India were rich merchants, bankers, and farmers, including the Bhatia, Lohana, and Baniya castes.[9] Many of these mercantile groups migrated to Bombay under British rule as the city was the political and financial capital of western India.[10] The merchant groups were headed by merchant-princes or seths who were heavily involved in the political and cultural milieu of Bombay. The seths, despite their general lack of education, ignorance of English language and British political traditions, were influential in Bombay society as leaders of business communities and maintainers of cultural honour.[11]

By the mid-nineteenth century the British had established political control over the Indian subcontinent and sought to create an administrative-legal framework to manage their colonial interests. British officials sought to compile Indian legal doctrines and apply them to British common law, effectively stripping native groups of civil and criminal self-governance in favour of a unified legal system. This desire to produce legal codes spawned the Orientalist school of Indology, whose grand narrative of Indian history was that of a decline from an ancient golden age into a degenerate, superstitious modern society. The British established schools and colleges that would educate new generations of Anglicized Indians who would be supportive of social reforms. These institutions created a new class of urban English speaking professionals who claimed to be superior leaders of society due to their intricate knowledge of the British administrative machinery. These English-speaking professionals joined various religious reform movements who concurred with the Orientalist view of modern Indian religion, and especially opposed the seths for their role in so-claimed excessive religious patronage.[11]

The Pushtimarg religious heads, the maharajas, began settling Bombay in the 19th century and by 1860 there were five maharajas in the city. The maharajas sought to exert control over their devotees and castes through seth intermediaries, and they were generally successful against anonymous reformers and caste solidarity. One such reformer was Karsandas Mulji, an English-educated reformer who was the editor of the Satyaprakash newspaper. Mulji came from an orthodox Pushtimarg merchant family who were highly respected in Bombay society; however Karsandas was disowned for his reformist views and had to drop out of Elphinstone College. Mulji became well known amongst Bombay reformists, and he launched attacks against the Pushtimarg and the Bombay maharajas for believed sexual depravity. Sexual allegations against the maharajas had first became public in 1855, and the senior-most maharaja in Bombay, Jivanlal, launched rebuttals against the reformers. Jivanlal attempted to silence criticism from Pushtimarg devotees by making his supporters sign a document that would censor their criticism of him under threat of excommunication.[12] Mulji decried Jivanlal's document as a "slavery bond", and in 1860 published a work claiming that Pushtimarg was a heretical sect which advocated sexual mistreatment of women. The Bombay maharajas then decided to bring in Jadunath Brijratan, a well-known maharaja from Surat, to defend their stances. Jadunath had several public and press debates with Mulji and other reformers.[13]

Eventually Jadunathjee Maharaj filed a libel case in the Bombay Supreme Court on 14 May 1861 against Karsandas Mulji, editor of Satyaprakash, a Gujarati weekly newspaper, and its publisher Nanabhai Rustomji Ranina, for defaming the plaintiff in an article published on 21 October 1860.[14]

Case and judgement

The defense's lawyers sought to have the case thrown out on the argument that Mulji's comments did not attack Jadunath personally but rather as a religious leader, and that a secular court did not have jurisdiction over religious matters. These attempts failed, and the British judges stated Jadunath had the right to defend his reputation in court, but that the case would give no value to Jadunath's status as a religious leader nor to Pushtimarg theology, but rather Jadunath would be treated as an ordinary citizen of the British empire whose actions would be viewed through the British laws of universal morality.[15]

Jadunath continued to use his traditional means of authority to defeat Mulji, and ordered seths to ensure the loyalty of devotees. In one instance Bhatia seths (including Gokuldas Lilahadhar) convened a meeting of two hundred people of their caste to further this aim. This meeting came to the attention of the British Supreme Court, which resulted in the Bhatia Conspiracy case in which the seths were convicted for mass witness tampering and forced to pay fines to the court.[16] That case made public the divisions growing in the devotional community over the status of the maharajas and their loyalty to them.[17]

Plaintiff's Case

Thirty-five witnesses were called by Jadunath's side to serve as character witnesses, all from mercantile castes and including several seths. The devotee witnesses did their best to defend Jadunath with the limited theological knowledge they possessed, but none knew Sanskrit or Braj Bhasha and were not fully versed in Pushtimarg history. One notable witness, Gopaldas Madhavdas, stated he did not know of any sexual immoralities conducted by Jadunath or any other maharaj, and stated they were highly honoured religious leaders of the merchant communities. Gopaldas viewed and venerated the maharajas as gurus rather than Krishna, but stated that others in the community did view the maharajas as incarnations of Krishna. Another witness, Jamunadas Sevaklal, gave a similar testimony stating he had no knowledge of immoralities or sexual orgies of the maharajas, and stated the maharajas in his view were gurus who were the representations of Krishna although others worshipped them as gods. When Gopaldas and Jamunadas were directly questioned on whether the maharajas were gods or humans, they were confused and could not provide definite answers.[18]

Jadunath himself took the stand, and claimed knowledge of Sanskrit, Braj Bhasha, and Gujarati, but then later stated he had never actually read any Braj Bhasha Pushtimarg text. When asked about certain texts that supported the veneration of maharajas, Jadunath stated he was personally unfamiliar with those texts and at one point in the trial claimed the Shrinathji Temple was in Kankroli rather than Nathdwara. Jadunath stated that the maharajas were simply mortal spiritual guides and that only their ancestor Vallabha was an incarnation of Krishna. He stated the veneration the maharajas received was in accordance with Hindu scriptures and that only the maharajas could directly worship the Krishna images, so devotees would worship the maharajas. He denied all sexual allegations relating to him and any other maharajas, stating the adulterous love of Krishna and the gopis in Vrindavan was merely a metaphor for the relationship between devotees and Krishna, not an endorsement of infidelity.[19]

Defense's Case

Karsandas Mulji himself took the stand, and stated the maharajas were oppressive leaders who encouraged sexual debauchery. He stated that Jadunath should rather be sued for libel, given his public attacks against Mulji. Mulji restated his earlier claims that the Pushtimarg was not the "true" Hinduism of the Vedic age, but rather a heretic sect that encouraged devotees to hand over their wives and daughters for the maharajas' pleasure.[20]

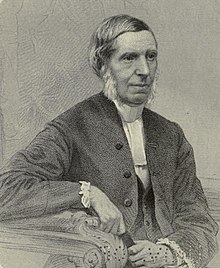

A missionary, Reverend John Wilson, also took the stand. Wilson claimed knowledge of Sanskrit and Old Hindi as well as the Vedas, Puranas, and Shastras, and was thus sent by the defense as an authority on Hinduism. Wilson however was not intimately familiar with the Pushtimarga, and referred to Professor H. H. Wilson's works on the sect. He criticized the maharajas for the practice of lavish seva to Krishna, which he stated was in opposition to the asceticism of "true" Hinduism. He stated the maharajas were uneducated spiritual leaders who were worshipped as incarnations of Krishna solely due to their genealogical descent from Vallabha, and that their religious scriptures sanctioned the offering of devotees' wives and daughters to them.[21]

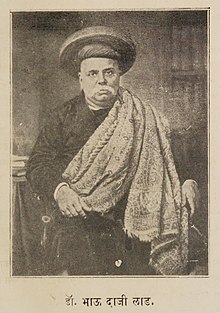

Two expert witnesses were also brought to the stand, Bhau Daji and Dhiraj Dalpatram, who were physicians to Jadunath. They said that they had treated Jadunath and other maharajas for syphilis, which they stated was due to sexual relations with female devotees. Dalpatram even stated that Jadunath had himself admitted to him that he had caught the disease from a female devotee.[22]

Other witnesses, such as Mathuradas Lowjee, supported the physician's testimonies. Lowjee was a member of the Pushtimarg, but ever since sexual allegations against the maharajas became public in 1855, he kept his distance from the maharajas and refused to venerate them all the while maintaining his theological commitment to the sect. He stated that Pushtimarg devotees, including members of his own Bhatia caste, viewed the maharajas as literal incarnations of Krishna. He stated senior members of the caste had "Ras Mandalis", which re-enacted the dances between Krishna and the gopis. He stated he once stumbled upon a maharaja having sexual intercourse with a female devotee. When Lowjee asked Jivanlal to stop the maharajas illicit behaviour, Jivanlal told him that he could not due to the powerful addiction of male sexual desire, as well as the fact that women's donations were a major source of financial income for the sect.[23]

Lakhmidas Khimji confirmed Lowjee's testimony, stating he once observed Jadunath grope the breasts of a fourteen year old girl and later stumbled upon Jadunath having sexual intercourse with her. Khimji stated on a few occasions he observed a widow companion of Jadunath procure married women for his sexual pleasure. Kalabhai Lalubhai also claimed Jadunath had sexual relations with women and girls as young as fourteen.[24]

Judgement

Justice Arnould

Justice Joseph Arnould ruled in favour of Mulji. Arnould was particularly influenced by Reverend Wilson's and Bhau Daji's testimonies. Arnould stated that Mulji's comments in Satyaprakash were not false and not specifically attacking Jadunath. Arnould agreed that the Pushtimarg was a degraded sect of Hinduism that promoted debauchery and loose morals. He stated Mulji did nothing wrong in exposing the "evil and barbarous" practices of the maharajas.[25]

Chief Justice Sausse

Chief Justice Matthew Richard Sausse was the senior of the two judges in the case, and overruled Arnould's judgement to find Mulji guilty of libel. Sausse was also greatly impressed by the defense's witnesses, which in his view affirmed the defendant's claim that the Pushtimarg was a heterodox sect and that Jadunath engaged in salacious behaviour. However, Sausse ruled that Mulji took a private dispute within the Pushtimarg and published his grievances in a public newspaper which was a form of malice. Sausse stated Mulji attacked Jadunath publicly without provocation, and that even if the sexual allegations against Jadunath were true, they were a private matter and newspapers could not attack people on private matters without public interest. Nevertheless, Sausse suspected the reliability of Jadunath and his witnesses' testimonies and only awarded him five rupees on the libel charge. Sausse sided with the defendants on the pleas that the Pushtimarg was a heterodox sect and agreed that the defendant's publications were true, and awarded Mulji eleven thousand five hundred rupees.[26][14][27]

Reaction

The libel case stirred unprecedented interest in the public. Karsandas Mulji's efforts and the court decision received praise from the liberals and the press.[14][28] For his part, Mulji was cited by the local English press as 'Indian Luther', after the Christian reformer Martin Luther.[29]

During and after the case, Pushtimarg devotees struggled to come to terms with the sexual allegations against the maharajas. Generally, devotees continued to have social contact with the maharajas as their religious leaders. In the next two decades however, some merchant devotees in Bombay built new temples and theological journals independent of the maharajas.[30]

In 1875, Dayananda Saraswati came to Bombay and attacked the Pushtimarg on similar lines as Mulji, calling it a heterodox sect with false religious leaders who contradicted "true" Hinduism.[31]

In popular culture

Maitri Goswami, Dhawal Patel et al. have written a book titled Doctrines of Pushtibhaktimarga: Allegations, Conspiracies and Facts (In context of Maharaj Libel Case)[6] based on the case.

Saurabh Shah, Gujarati author and journalist, wrote a novel titled Maharaj based on the case[32] which was awarded the Nandshankar award by the Narmad Sahitya Sabha.[33]

Netflix's 2024 period drama film Maharaj, directed by Siddharth P. Malhotra and produced by Aditya Chopra under YRF Entertainment starring Aamir Khan’s son Junaid Khan (in his debut) and Jaideep Ahlawat, is based on the Maharaj Libel Case and Saurabh Shah's novel. The Gujarat High Court stayed the release of the film, based on a Hindu group's plea that claimed the film could incite violence against followers of Pushtimarga Sampradaya.[34][35] It was finally released on 21 June 2024 for streaming on Netflix.[36]

References

- ^ "More controversy brews after stay order on movie 'Maharaj'".

- ^ "'Maharaj' review: A royal slog".

- ^ "Maharaj movie review: Junaid Khan and his debut are both strictly passable".

- ^ "As 'Maharaj' is stayed, issue of freedom of expression raised in 1862 libel case returns to life".

- ^ Shodhan, A. (1997). "Women in the Maharaj libel case: a re-examination". Indian Journal of Gender Studies. 4 (2): 123–39. doi:10.1177/097152159700400201. PMID 12321343. S2CID 25866333.

- ^ a b Patel, Dhawal; Goswami, Maitri; Sharma, Utkarsha; Shirodariya, Umang; Bhatt, Ami; Mehrishi, Pratyush; Goswami, Sharad (2021-04-21). Doctrines of Pushtibhaktimarga: A True representation of the views of Sri Vallabhacharya: In the context of Maharaj Libel Case (in Hindi). Shree Vallabhacharya Trust, Mandvi - Kutch. ISBN 978-93-82786-37-5.

- ^ * Barz, Richard (2018). "Vallabha Sampradāya/Puṣṭimārga". In Jacobsen, Knut A.; Basu, Helene; Malinar, Angelika; Narayanan, Vasudha (eds.). Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism Online. Brill.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 255.

- ^ Thakkar 1997, p. 48.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 269.

- ^ a b Saha 2004, p. 258-279.

- ^ "The untold story of Karsandas Mulji, the journalist who won the fight against the Maharaj". The Indian Express. 2024-07-01. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 281-289.

- ^ a b c Thakkar 1997, p. 46–52.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 290-291.

- ^ Mehta, Makarand (2002). Gujarati Vishwakosh (Gujarati Encyclopedia). Vol. 15. Ahmedabad: Gujarati Vishwakosh Trust. p. 451.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 291-293.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 293-296.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 296-298.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 298-299.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 299-300.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 300-301.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 301-303.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 303.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 304.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 304-306.

- ^ Maharaj Libel Case Including Bhattia Conspiracy Case, No. 12047 o f 1861, Supreme Court Plea Side: Jadunathjee Birzrattanjee Maharaj Vs Karsondass Mooljee and Nanabhai Rustamji. Bombay: D. Lukhmidass & Co. 1911. pp. 399, 419.

- ^ Yagnik, Achyut (2005-08-24). Shaping Of Modern Gujarat. Penguin UK. pp. 93–94. ISBN 9788184751857.

- ^ Kumar, Anu (9 September 2017). "The Long History of Priestly Debauchery". Economic and Political Weekly. 52 (36). Mumbai: 79–80. eISSN 2349-8846. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 26697565.(subscription required)

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 307.

- ^ Saha 2004, p. 209.

- ^ Shah, Saurabh (2014-01-18). Maharaj - Gujarati eBook. R R Sheth & Co Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9789351221708.

- ^ Shah, Saurabh (2014-01-18). Maharaj - Gujarati eBook. R R Sheth & Co Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789351221708.

- ^ "Court stays release of 'Maharaj', here's everything you need to know about Maharaj Libel Case of 1862".

- ^ dkbj (2024-06-06). "Junaid Khan-starrer 'Maharaj' went through 30 writing drafts, 100-plus narrations » Yes Punjab - Latest News from Punjab, India & World". Yes Punjab - Latest News from Punjab, India & World. Retrieved 2024-06-14.

- ^ "Ira Khan, Kiran Rao Form Junaid's Cheer Squad After Release Of His Debut Film Maharaj".

Sources

- Saha, Shandip (2004). Creating a Community of Grace: A History of the Puṣṭi Mārga in Northern and Western India (1493-1905) (Thesis). University of Ottawa.

- Lütt, Jürgen (1987). "Max Weber and the Vallabhacharis". International Sociology. 2 (3): 277–287. doi:10.1177/026858098700200305. S2CID 143677162.

- Scott, J. Barton (2015). "How to Defame a God: Public Selfhood in the Maharaj Libel Case". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 38 (3): 387–402. doi:10.1080/00856401.2015.1050161. hdl:1807/95441. S2CID 143251675.

- Haberman, David L. (1993-08-01). "On Trial: The Love of the Sixteen Thousand Gopees". History of Religions. 33 (1): 44–70. doi:10.1086/463355. ISSN 0018-2710. S2CID 162268682.

- Thakkar, Usha (4 January 1997). "Puppets on the Periphery-Women and Social Reform in 19th Century Gujarati Society". Economic and Political Weekly. 32 (1–2). Mumbai: 46–52. ISSN 0012-9976.(subscription required)