| Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

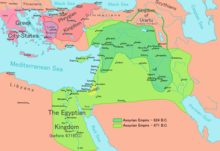

Map of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 824 BC (dark green) and in its apex in 671 BC (light green), under King Esarhaddon | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Medes Babylonians |

Assyrians Egypt | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Cyaxares Nabopolassar |

Sinsharishkun † Ashur-uballit II †(?) Necho II | ||||||

The Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire was the last war fought by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, between 626 and 609 BC. Succeeding his brother Ashur-etil-ilani (r. 631–627 BC), the new king of Assyria, Sinsharishkun (r. 627–612 BC), immediately faced the revolt of one of his brother's chief generals, Sin-shumu-lishir, who attempted to usurp the throne for himself.

Though this threat was dealt with relatively quickly, the instability caused by the brief civil war may have made it possible for another official or general, Nabopolassar (r. c. 626 – 605 BC), to rise up and seize power in Babylonia.

Sinsharishkun's inability to defeat Nabopolassar, despite repeated attempts over the course of several years, allowed Nabopolassar to consolidate power and form the Neo-Babylonian Empire, restoring Babylonian independence after more than a century of Assyrian rule. The Neo-Babylonian Empire, and the newly-formed Median Empire under King Cyaxares (r. 625–585 BC), then invaded the Assyrian heartland. In 614 BC, the Medes captured and sacked Assur, the ceremonial and religious heart of the Assyrian Empire, and in 612 BC, their combined armies attacked and razed Nineveh, the Assyrian capital.

Sinsharishkun's fate is unknown but it is assumed that he died in the defense of his capital. He was succeeded as king only by Ashur-uballit II (r. 612–609 BC), possibly his son, who rallied what remained of the Assyrian army at the city of Harran and, bolstered by an alliance with Egypt, ruled for three years, in a last attempt to resist the Medo-Babylonian invasion of his realm.

Background

In the first half of the seventh century, the Neo-Assyrian Empire was at the height of its power, controlling the entire Fertile Crescent, and allied with Egypt. However, when Assyrian king Assurbanipal died of natural causes in 631 BC,[4] his son and successor Ashur-etil-ilani was met with opposition and unrest, a common occurrence in Assyrian history.[5] An Assyrian official called Nabu-rihtu-usur attempted to usurp the Assyrian throne with the help of another official, Sin-shar-ibni, but the king, likely with the help of Sin-shumu-lishir, stopped Nabu-rihtu-usur and Sin-shar-ibni crushing the conspiracy relatively quickly.[4][5] However, it is possible that some of Assyria's vassals used the reign of what they perceived to be a weak ruler to free themselves from Assyrian control and even attack Assyrian outposts. In c. 628 BC, Josiah, an Assyrian vassal and the king of Judah in the Levant, extended his land so that it reached the coast, capturing the city of Ashdod and settling some of his own people there.[6] Ashur-etil-ilani's end is unclear, but it is frequently assumed, without any supporting evidence, that Ashur-etil-ilani's brother Sinsharishkun fought with him for the throne and,[7] ultimately, ascended to the throne in the middle of 627 BC.[8] Roughly at the same time, the vassal king of Babylon, Kandalanu, died which led to Sinsharishkun also becoming the ruler of Babylon, as proven by inscriptions by him in southern cities such as Nippur, Uruk, Sippar and Babylon itself.[9] Around this time, the Neo-Assyrian Empire was also in the midst of a 125-year-long megadrought stretching from 675 to 550 BC, which further weakened the empire.[10]

Course of the war

Rise of Babylon

Sinsharishkun's rule of Babylon did not last long, as almost immediately in the wake of him coming to the throne, the general Sin-shumu-lishir rebelled.[8] Sin-shumu-lishir was a key figure during Ashur-etil-ilani's reign, putting down several revolts and possibly being the de facto leader of the country. The new king might have endangered his position, therefore he revolted in an attempt to seize power for himself.[9] Sin-shumu-lishir seized some cities in northern Babylonia, including Nippur and Babylon itself and would rule there for three months before being defeated by Sinsharishkun.[8] Nabopolassar, possibly using the political instability caused by the previous revolt and the ongoing interregnum in the south,[8][11] assaulted both Nippur and Babylon.[n 1] and in the aftermath of a failed Assyrian counterattack, Nabopolassar was formally crowned King of Babylon on November 22/23, 626 BC, restoring Babylonia as an independent kingdom.[12]

In 625–623 BC, Sinsharishkun's forces again attempted to defeat Nabopolassar, campaigning in northern Babylonia. The Assyrian campaigns were initially successful, seizing the city of Sippar in 625 BC and repelling Nabopolassar's attempt to reconquer Nippur. Another Assyrian vassal, Elam, also stopped paying tribute to Assyria during this time and several Babylonian cities, such as Der, revolted and joined Nabopolassar. Realizing the threat this posed, Sinsharishkun led a massive counterattack himself which saw the successful recapture of Uruk in 623 BC.[13] Sinsharishkun could possibly have ultimately been victorious but another revolt, led by an Assyrian general, occurred in the empire's western provinces in 622 BC.[13] This general, whose name remains unknown, took advantage of the absence of Sinsharishkun's forces to march on Nineveh, met an army which surrendered without fighting and successfully seized the Assyrian throne. The surrender of the army indicates that the usurper was an Assyrian and possibly even a member of the royal family, or at least a person that would be acceptable as king.[14] Sinsharishkun then abandoned his Babylonian campaign to defeat the usurper, accomplishing the task after roughly a hundred days of civil war; however the absence of the Assyrian army saw the Babylonians conquer the last remaining Assyrian outposts in Babylonia in 622–620 BC.[13] The Babylonian siege of Uruk had begun by October 622 BC, and though control of the ancient city would shift between Assyria and Babylon, it was firmly under Babylonian rule by 620 BC,[15] and Nabopolassar consolidated his rule over the entirety of Babylonia.[16] During the next several years, the Babylonians scored several other victories against the Assyrians and by 616 BC, Nabopolassar's forces had reached as far as the Balikh River. Pharaoh Psamtik I, Assyria's ally, marched his forces to help Sinsharishkun. The Egyptian Pharaoh had over the last few years campaigned in order to establish dominance over the small city-states of the Levant, and it was in his interests that Assyria survived as a buffer state between his own empire and those of the Babylonians and Medes in the east.[16] A joint Egyptian-Assyrian campaign to capture the city of Gablinu was undertaken in October of 616 BC, but ended in defeat, after which the Egyptian allies kept to the west of the Euphrates, only offering limited support.[17] In 616 BC, the Babylonians defeated the Assyrian forces at Arrapha and pushed them back to the Little Zab.[18] Nabopolassar failed to seize Assur, the ceremonial and religious center of Assyria, in May of the next year, forcing him to retreat to Takrit, but the Assyrians were unable to capture Takrit and end his rebellion.[17]

Medes' intervention

In October or November 615 BC, the Medes under King Cyaxares invaded Assyria and conquered the region around the city of Arrapha in preparation for a great final campaign against the Assyrians.[17] That same year, they defeated Sinsharishkun at the Battle of Tarbisu, and in 614 BC, they conquered Assur, plundering the city and killing many of its inhabitants.[1][18][19][20] Nabopolassar only arrived at Assur after the plunder had already begun and met with Cyaxares, allying with him, signing an anti-Assyrian pact and Nebuchadnezzar, son of Nabopolassar married a Median princess. Shortly after, Sinsharishkun made his last attempt at a counterattack, rushing to rescue the besieged city of Rahilu, but Nabopolassar's army had retreated before a battle could take place.[21] In 612 BC, the Medes and Babylonians joined their forces to besiege Nineveh, taking the city after a lengthy and brutal siege, with the Medes playing a major part in the city's downfall.[21][22][23][24] Although Sinsharishkun's fate is not entirely certain, it is commonly accepted that he died in the defense of Nineveh.[25][26]

After the destruction of Assur in 614 BC, the traditional Assyrian coronation was impossible,[27] so Ashur-uballit II was crowned in Harran, which he made his new capital. While the Babylonians saw him as the Assyrian king, the few remaining subjects Ashur-uballit II governed likely did not share this view, and his formal title remained crown prince (mar šarri, literally meaning "son of the king").[28] However, Ashur-uballit not formally being king does not indicate that his claim to the throne was challenged, only that he had yet to go through with the traditional ceremony.[29] Ashur-uballit's main objective would have been to retake the Assyrian heartland, including Assur and Nineveh. Bolstered by the forces of his allies, Egypt and Mannea, this ambition was quite possible, and his temporary rule from Harran as crown prince, rather than legitimately crowned king, may have seemed more like a temporary circumstance. Instead, Ashur-uballit's rule at Harran composes the final years of the Assyrian state, which at this point, had effectively ceased to exist as an Empire.[2][29][30] After Nabopolassar himself had travelled the recently conquered Assyrian heartland in 610 BC in order to ensure stability, the Medo-Babylonian army embarked on a campaign against Harran in November of 610 BC.[30] Intimidated by the approach of the Medo-Babylonian army, Ashur-uballit and a contingent of Egyptian reinforcements fled the city into the deserts of Syria.[31] The siege of Harran lasted from the winter of 610 BC to the beginning of 609 BC, and the city eventually capitulated.[32] Ashur-uballit's failure at Harran ended the ancient Assyrian monarchy, which would never be restored.[33]

After the Babylonians had ruled Harran for three months, Ashur-uballit, along with a large force of Egyptian soldiers attempted to retake the city, launching a siege in June or July of 609 BC.[31][34] His siege lasted at most two months, until August or September, before being forced to retreat by Nabopolassar; they may have retreated even earlier.[34]

Aftermath

The eventual fate of Ashur-uballit is unknown and his siege of Harran in 609 BC is the last time he, or the Assyrians in general, are mentioned in Babylonian records.[31][34] After the battle at Harran, Nabopolassar resumed his campaign against the remainder of the Assyrian army in the beginning of the year 608 or 607 BC. It is thought that Ashur-uballit was still alive at this point, for in 608 BC, the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II, Psamtik I's successor, personally led a large Egyptian army into former Assyrian territory to rescue his ally and turn the tide of the war. There is no mention of a large battle between the Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians and Medes in 608 BC, which would have been mentioned in contemporary sources as it marked conflict of the four greatest military powers of their day, and there are no later mentions of Ashur-uballit, it is possible he died at some point during 608 BC, before such a battle could occur.[31] The historian M.B. Rowton speculates Ashur-uballit could have lived until 606 BC,[31] however, by this time, references to the Egyptian army in Babylonian sources bear no reference to the Assyrians or their king.[27]

Although Ashur-uballit is no longer mentioned after 609 BC, the Egyptian campaigns in the Levant continued for some time until a crushing defeat at the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BC. Throughout the next century, Egypt and Babylon, brought into direct contact with each other through Assyria's fall, would frequently be at war with each other over control in the Fertile Crescent.[34][35]

Notes

References

- ^ a b Liverani 2013, p. 539.

- ^ a b Frahm 2017, p. 192.

- ^ Curtis 2009, p. 37.

- ^ a b Ahmed 2018, p. 121.

- ^ a b Na’aman 1991, p. 255.

- ^ Ahmed 2018, p. 129.

- ^ Ahmed 2018, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d Lipschits 2005, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Na’aman 1991, p. 256.

- ^ Mary Caperton Morton (15 January 2020). "Megadrought Helped Topple the Assyrian Empire". Eos. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ Beaulieu 1997, p. 386.

- ^ Lipschits 2005, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Lipschits 2005, p. 15.

- ^ Na’aman 1991, p. 263.

- ^ Boardman 1992, p. 62.

- ^ a b Lipschits 2005, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Lipschits 2005, p. 17.

- ^ a b Boardman 2008, p. 179.

- ^ Bradford 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Potts 2012, p. 854.

- ^ a b Lipschits 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Frahm 2017, p. 194.

- ^ Dandamayev & Grantovskiĭ 1987, pp. 806–815.

- ^ Dandamayev & Medvedskaya 2006.

- ^ Yildirim 2017, p. 52.

- ^ Radner 2019, p. 135.

- ^ a b Reade 1998, p. 260.

- ^ Radner 2019, pp. 135–136.

- ^ a b Radner 2019, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b Lipschits 2005, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e Rowton 1951, p. 128.

- ^ Bertman 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Radner 2019, p. 141.

- ^ a b c d Lipschits 2005, p. 20.

- ^ Edwards 1970, p. 14.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Sami Said (3 December 2018). Southern Mesopotamia in the time of Ashurbanipal. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-139617-0.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1997). "The Fourth Year of Hostilities in the Land". Baghdader Mitteilungen. 28: 367–394.

- Bertman, Stephen (14 July 2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-518364-1.

- Boardman, John (16 January 1992). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22717-9.

- Boardman, John (28 March 2008). The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 3, Part 2, The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

- Bradford, Alfred S. (2001). With Arrow, Sword, and Spear: A History of Warfare in the Ancient World. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-95259-4.

- Curtis, Adrian (16 April 2009). Oxford Bible Atlas. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-162332-5.

- Dandamayev, M.; Grantovskiĭ, È. (1987). "ASSYRIA i. The Kingdom of Assyria and its Relations with Iran". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 8. pp. 806–815.

- Dandamayev, M.; Medvedskaya, I. (2006). "MEDIA". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen (1970). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22804-6.

- Frahm, Eckart (12 June 2017). A Companion to Assyria. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3593-4.

- Lipschits, Oded (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah Under Babylonian Rule. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-095-8.

- Liverani, Mario (4 December 2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-75084-9.

- Na’aman, Nadav (1991). "Chronology and History in the Late Assyrian Empire (631—619 B.C.)". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie. 81 (1–2): 243–267. doi:10.1515/zava.1991.81.1-2.243. S2CID 159785150.

- Potts, Daniel T. (15 August 2012). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-6077-6.

- Radner, Karen (2019). "Last Emperor or Crown Prince Forever? Aššur-uballiṭ II of Assyria according to Archival Sources". State Archives of Assyria Studies. 28: 135–142.

- Reade, J. E. (1998). "Assyrian eponyms, kings and pretenders, 648–605 BC". Orientalia (NOVA Series). 67 (2): 255–265. JSTOR 43076393.

- Rowton, M. B. (1951). "Jeremiah and the Death of Josiah". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 2 (10): 128–130. doi:10.1086/371028. S2CID 162308322.

- Yildirim, Kemal (2017). "Diplomacy in Neo-Assyrian Empire (1180-609) Diplomats in the Service of Sargon II and Tiglath-Pileser III, Kings of Assyria". International Academic Journal of Development Research. 5 (1): 128–130.