| |

| Author | John Ryan, George Dunford and Simon Sellars |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Micronationalism |

| Published | September 2006 |

| Publisher | Lonely Planet |

| Publication place | Australia |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 160 |

| ISBN | 978-1-74104-730-1 |

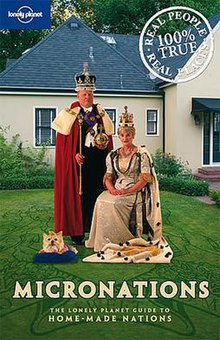

Micronations: The Lonely Planet Guide to Home-Made Nations is an Australian gazetteer about micronations, published in September 2006 by Lonely Planet. It was written by John Ryan, George Dunford and Simon Sellars. Self-described as a humorous guidebook and written in a light-hearted tone, the book's profile of micronations offers information on their flags, leaders, currencies, maps and other facts. It was re-subtitled Guide to Self-Proclaimed Nations in later publications.

Ryan first became interested in the concept of micronationalism upon his discovery of the Principality of Hutt River. While pitching the idea to the staff at Lonely Planet, Sellars, who founded his own micronation as a child, overheard Ryan and pestered him for several months after the book's concept had been approved by the publisher until Ryan finally agreed to accept him as a co-writer. Dunford was later also invited by Ryan.

Background and publication

Context

Micronations are political entities that claim independence and mimic acts of sovereignty as if they were a sovereign state, but lack any legal recognition. They are classified separately from states with limited recognition or quasi-states as they lack the legal basis in international law for their existence.[1] According to Collins English Dictionary, many exist "only on the internet or within the private property of [their] members"[2] and seek to simulate a state rather than to achieve international recognition; their activities are generally non-threatening, often leading sovereign states to not actively contest the territorial claims they put forth.[3][4] The word micronation has no basis in international law.[5] Lonely Planet is a travel guide publisher based in Australia.[6]

The earliest-published book about micronationalism was How to Start Your Own Country (1979) by libertarian science-fiction author Erwin S. Strauss, in which Strauss documents various approaches to sovereignty and their chances of success.[7] It has since been dubbed the seminal work on the topic.[8] This was followed by two French-language publications—L'Etat c'est moi: histoire des monarchies privées, principautés de fantaisie et autres républiques pirates in 1997 by French writer and historian Bruno Fuligni and Ils ne siègent pas à l'ONU in 2000 by Swiss academic Fabrice O'Driscoll, who also founded the French Institute of Micropatrology.[9][10]

Development and publication

Micronations: The Lonely Planet Guide to Home-Made Nations—later re-subtitled Guide to Self-Proclaimed Nations—was published in September 2006 by Lonely Planet as a "fully illustrated, humorous mock-guidebook" to micronations.[7][10] The book is authored by Australian journalist John Ryan, freelance journalist George Dunford, and writer and blogger Simon Sellars.[P 1] Ryan, the principal author of the book, became interested in the concept of micronationalism upon his discovery of the Principality of Hutt River located in Australia. After further researching the topic and finding out about the Conch Republic in the United States, Ryan became even more inspired by micronations, saying that as he kept researching "[He] just saw that there were these strange little nations popping up all over the place."[11][12]

According to Sellars in an interview with BLDGBLOG, he overheard Ryan discussing the idea for a book about micronations with one of the Lonely Planet staff while he was working as an editor for the company. Upon hearing it had been approved, Sellars pestered Ryan for several months until Ryan agreed to accept him as a co-writer. Dunford was later also invited by Ryan. Sellars—who founded his own micronation when he was a kid—became interested in the concept because of his fondness of parallel universes in fiction—"anything that distorts or reflects or comments on the 'real' world – or sets up an alternative world".[13]

Content

Micronations: The Lonely Planet Guide to Home-Made Nations has 160 pages, and includes an introduction and a full index.[P 2] It is fully illustrated.[14] The book's profile of micronations offers information on their flags, leaders, currencies, maps and other facts. Sidebars throughout the book provide overviews of such topics as coinage and stamps, as well as a profile of Emperor Norton. Micronations: The Lonely Planet Guide to Home-Made Nations is split into three parts: "Serious Business",[P 3] which includes what the authors equate as serious secessionist attempts, "My Backyard, My Nation",[P 4] which includes local and jocular micronations, and "Grand Dreams",[P 5] which includes largely imaginative micronations.

Below are the micronations featured in the book, ordered by section:

Serious Business

- Principality of Sealand, United Kingdom

- Freetown Christiania, Denmark

- Principality of Hutt River, Australia

- Kingdom of Lovely, United Kingdom

- Whangamomona, New Zealand

- Gay and Lesbian Kingdom of the Coral Sea Islands, Australia

- Kingdom of Elleore, Denmark

- Sovereign Military Order of Malta (not a micronation)[a]

- Akhzivland, Israel

- Northern Forest Archipelago, United States

- Principality of Seborga, Italy

- Freedonia, United States

- Great Republic of Rough and Ready, United States

My Backyard, My Nation

- Republic of Molossia, United States

- Empire of the United States, United States

- Copeman Empire, United Kingdom

- Empire of Atlantium, Australia

- North Dumpling Island, United States

- Republic of Kugelmugel, Austria

- Grand Duchy of the Lagoan Isles, United Kingdom

- Kingdom of Vikesland, Canada

- Great United Kiseean Kingdom, Finland and Romania

- Kingdom of Romkerhall, Germany

- Ibrosian Protectorate, United Kingdom

- Sovereign Kingdom of Kemetia, United Kingdom

- Kingdom of Talossa, United States

- Aerican Empire, United States

- Republic of Cascadia, United States and Canada

- Principality of Trumania, United States

- Kingdom of Redonda, Antigua and Barbuda

Grand Dreams

- Grand Duchy of Westarctica, Antarctica

- Borovnia, fictional

- Maritime Republic of Eastport, United States

- Republic of Rathnelly, Canada

- Republic of Saugeais, France

- Barony of Caux, France

- Nutopia, non-territorial

- Conch Republic, United States

- Le Royaume de L'Anse-Saint-Jean, Canada

- Royal Republic of Ladonia, Sweden

- Dominion of British West Florida, United States

- Grand Duchy of Elsanor, United States

- Principality of Snake Hill, Australia

- SoS (State of Sabotage), Finland

Critical reception

Peter Needham, writing for The Australian, and Jesse Walker, in The American Conservative, both appreciated the book's light-hearted approach to micronations. Needham, extending his appreciation to the work's approach to politics, called the book "amusing"[16] while Walker compared it to Strauss' How to Start Your Own Country and reflected that Micronations had a greater focus on whimsical "tongue-in-cheek projects", citing Molossia as an example.[12] Jo Sargent, writing in The Geographical Magazine, was more critical, saying that while he thinks Lonely Planet produces excellent guidebooks, Micronations was more limited to eccentric micronational leaders rather than their micronations.[17]

Needham also appreciated the work's scope, quipping that "the prospect of a listing in future editions" would be an added incentive to those wanting to found their own micronations.[16] Conversely, Sargent thought that, although the book was amusing at first and has some interesting entries, the large number of micronations eventually becomes uninteresting. He stated that there is only "so many 'wacky' young men deciding that life is unfair and setting up a nation in their bedroom" that one can read about before getting bored.[17] Walker concluded their review by saying that the book makes for "entertaining reading," and wrote that it might be useful as an actual guide to the profiled micronations if one wished to visit them.[12]

See also

- Micronations and the Search for Sovereignty (2021)

- How to Rule Your Own Country: The Weird and Wonderful World of Micronations (2022)

- List of micronations

Footnotes

References

Primary sources

References which are cited to the book itself:

- ^ Ryan, Dunford & Sellars 2006, pp. 153–54: "The Authors"

- ^ Ryan, Dunford & Sellars 2006, "Table of contents"

- ^ Ryan, Dunford & Sellars 2006, pp. 7–60

- ^ Ryan, Dunford & Sellars 2006, pp. 61–108

- ^ Ryan, Dunford & Sellars 2006, pp. 109–152

Source

- Ryan, John; Dunford, George; Sellars, Simon (2006). Micronations: The Lonely Planet Guide to Home-Made Nations. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-730-1.

Secondary sources

- ^ Hobbs & Williams 2021, pp. 76–78.

- ^ "Micronation". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. n.d. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Oeuillet, Julien (7 December 2015). "Springtime of micronations spearheaded by Belgian "Grand-Duke" Niels". The Brussels Times. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Moreau, Terri Ann (2014). Subversive Sovereignty: Parodic Representations of Micropatrias Enclaved by the United Kingdom (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of London. p. 138. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Grant, John P.; Barker, J. Craig, eds. (2009). "micronations". Encyclopaedic Dictionary of International Law (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-195-38977-7. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023 – via Oxford Reference.

- ^ Fildes, Nic (2 October 2007). "BBC gives Lonely Planet guides a home in first major acquisition". The Independent. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ a b McDougall, Russel (15 September 2013). "Micronations of the Caribbean". In Fumagalli, Maria Cristina; Hulme, Peter; Robinson, Owen; Wylie, Lesley (eds.). Surveying the American Tropics: A Literary Geography from New York to Rio. Liverpool University Press. p. 233. doi:10.5949/liverpool/9781846318900.003.0010. ISBN 978-1-84631-8-900.

- ^ de Castro, Vicente Bicudo (11 March 2022). "Harry Hobbs and George Williams' Micronations and the Search for Sovereignty" (PDF). Shima. 16 (1). Shima Publishing: 422. doi:10.21463/shima.159. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Foucher-Dufoix, Valérie; Dufoix, Stéphane (February 2012). "La patrie peut-elle être virtuelle ?" [Can the homeland be virtual?]. Pardés (in French). 52. In Press: 17. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023 – via Cairn.info.

- ^ a b Vieira, Fátima (2022). "Micronations and Hyperutopias". In Marks, Peter; Wagner-Lawlor, Jennifer A.; Vieira, Fátima (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Utopian and Dystopian Literatures. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 282. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-88654-7_22. ISBN 978-3-030-88654-7.

- ^ Chadwick, Alex (1 November 2007). "'Lonely Planet' Explores Micronations". NPR. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Walker, Jesse (19 November 2007). "Big Ideas Need Small Places". The American Conservative. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ Manaugh, Geoff (23 November 2006). "The Lonely Planet Guide to Micronations: An Interview with Simon Sellars". BLDGBLOG. Archived from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Micronations / John Ryan ; George Dunford ; Simon Sellars". National Library of Australia. n.d. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ Hobbs & Williams 2021, p. 73.

- ^ a b Needham, Peter (16 September 2006). "Born to rule". The Australian. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ a b Sargent, Jo (October 2006). "It's a small world after all". The Geographical Magazine. Vol. 78, no. 10. Geographical Magazine Ltd. p. 91. ISSN 0016-741X.

Bibliography

- Hobbs, Harry; Williams, George (2021). Micronations and the Search for Sovereignty. Cambridge Studies in Constitutional Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-15013-2. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2023.