| Nyatapola | |

|---|---|

𑐒𑐵𑐟𑐵𑐥𑑀𑐮 | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hindusim |

| District | Bhaktapur |

| Province | Bagmati Province |

| Deity | Devi in the form of Siddhi Lakshmi[1] |

| Location | |

| Location | Tamārhi tvā Bhaktapur, Nepal |

| Country | Nepal |

| Geographic coordinates | 27°40′17″N 85°25′43″E / 27.67139°N 85.42861°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Traditional Nepalese architecture[2] |

| Founder | Bhupatindra Malla |

| Completed | 15 July 1702 |

| Specifications | |

| Height (max) | 33.23 m (108.26 ft)[3] |

| Elevation | 1,401 m (4,596 ft)[3] |

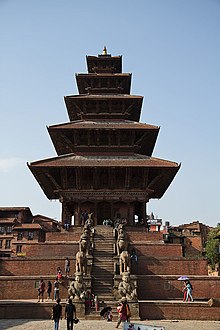

Nyātāpola (from Nepal Bhasa: 𑐒𑐵𑐟𑐵𑐥𑑀𑐮, "ṅātāpola", lit. 'something with five storey') is a five tiered temple located in the central part of Bhaktapur, Nepal.[4][5] It is the tallest monument within the city and is also the tallest temple of Nepal. This temple was commissioned by King Bhupatindra Malla, the construction of which lasted for six months from December 1701 to July 1702.[6] The temple has survived four major earthquakes and its aftershocks including the recent 7.8 magnitude April 2015 earthquake which caused major damage the city of Bhaktapur.[7]

The Nyatapola is noted for its unique architecture as it is one of only two five storey temples in the Kathmandu Valley, the other one being the Kumbheshvara in Lalitpur and its five level plinth which along with steps to the top part also contains pairs of stone statues of animals and deities serving as the temple's guardians.[8] Along with the Bhairava temple and other historical monuments, the Nyatapola forms the Tamārhi square, which forms the central and culturally the most important part of Bhaktapur and a popular tourist destination.

The temple itself has no religious significance to the locals; it is culturally used as a symbol of Bhaktapur. Its silhouette is used by the municipality in its coats of arms as well as by most of the corporations of the city. Reaching to a height of 33 m (108.26 ft), the Nyatapola temple dominates the skyline of Bhaktapur and is the tallest monument there.[4] The Nyatapola Square also divides the town of Bhaktapur into two parts: Thané (lit. 'Upper one') and Konhé (lit. 'Lower one').[9]

The gates of the temple is only opened once a year in July on the anniversary of its establishment during which the Avāla subgroup of the Newars plant a triangular flag on its top and the Karmacharya priests perform a ritual on the deity.[10] Since the public is not allowed in, the deity housed inside is also not known to the public although it is generally accepted that the temple houses a powerful Tantric incarnation of the mother goddess.[4] Even the contemporary manuscript dealing with the construction of the temple does not mention the name of the deity housed inside.[11]

Etymology

Nyatapola is regarded as unique in terms of its name as it one of the only few temples which is not named after the deity residing inside it.[5] Its name is derived from the local Nepal Bhasa name "ṅātāpola", where "ṅātā" means something with five storey while "pola" means roof in the Bhaktapur dialect of Nepal Bhasa .[8] Newar people outside of Bhaktapur use the term "Nyātāpau", where "nyātā" and "pau"has the same meaning as "ṅātā" and "pola".[12]

The name "𑐒𑐵𑐟𑐵𑐥𑑀𑐮 (ṅātāpola)" has been in use since its construction as the temple was referred as such in the ledger of its construction work.[3] Historian Purushottam Lochan Shrestha found a damaged stone inscription being used as a step ladder by soldiers housed in Bhaktapur Durbar Square which uses uses the word "𑐒𑐵𑐟𑐵𑐥𑑀𑐮 (ŋ̊ātāpola)" to refer to the temple.[13] Raj Man Singh Chitrakar who drew a sketch of the Nyatapola temple in 1844 has inscribed this temple as "Gniato Polo temple of Devi".[14] Similarly, Henry Ambrose Oldfield who painted this temple in 1854 has inscribed this temple as "Temple of Devi Bhagwati at Bhatgaon".[15]

History

Sources

Contrary to most of the temples and other important buildings from the Malla dynasty, a stone inscription affiliated to the Nyatapola, which is traditionally attached to the temple itself has not been found.[17] Historian Purushottam Lochan Shrestha found an extremely damaged stone inscription in Bhaktapur Durbar Square being used as a step ladder by the soldiers quartered there in which the name of the temple and a date in which was the date when the temple was consecrated was inscribed.[13] So, far it is the only Malla dynasty stone inscription in which its name is inscribed.

Therefore, the main source about the construction history of the Nyatapola comes from a palm leaf manuscript named as "siddhāgni koṭyāhuti devala pratiṣṭhā" by modern scribes.[18] It is a ledger written in Nepal Bhasa contains the name, wage and work time of every single person who contributed in the construction, details and cost of every single religious ritual performed and the detailed time line of the construction.[3] The manuscript began with the following sentence:

Hail the god Ganesha. After performing a siddhāgni koṭyāhuti yagya, Maharaja Bhupatindra Malla inaugurated the Nyatapola temple.[19]

The construction of the Nyatapola was completed in a short period of six months mainly because all the required materials were already preapred.[20] Similarly, citizens from most cities within the Kingdom of Bhaktapur and the Kingdom of Lalitpur either directly helped in the construction or donated raw materials for it.[21]

In Nepalese architecture, wood and bricks are the main materials for construction. For the Nyatapola, timber was collected from November 1701. Workers from all the settlements within the Kingdom of Bhaktapur were sent to nearby forest of Bhaktapur to chop down Sal trees.[22] The workers were sent in groups based on their hometown and worked for at least a month and were paid based on the amount of days they worked.[23] The first group which contained nineteen woodcutters from Thimi were paid an average of 112 dam per 28 days of work.[22] The second group contained eight cutters from Banepa and twenty one from Thimi.[24] A total of 29 mohar and 14 dam were paid to this group who on average worked for 30 days.[24] The third group contained eight cutters form the town of Khampu were paid 7 mohar and 8 dam in total while twelve workers from Bhaktapur were paid 7 mohar and 40 dam.[25] Another group containing seventeen workers form Panauti worked for 32 days on average and were paid 20 mohar and 20 dam in total.[26] Sixteen workers from Nala worked for 30 days on average and were paid 17 mohar and 20 dam in total while thirteen workers from Sāngā were paid 15 mohar and 36 dam in total.[27] Lastly, fourteen workers from Dhulikhel were paid 14 mohar and 12 dam in total.[28] Among the woodcutters, most workers worked am average of 30 days; the workers form Bhaktapur worked the fewest in total.[22] A cutter from Bhaktapur named Bvāsama worked for eight days, the least among the cutters and was paid 32 dams while a few cutters from Thimi, Sāngā, Dhulikhel, Panauti and Banepa worked for 39 days, the highest among the workers and were paid 1 mohar and 37 dam for it.[24]

Apart from that Sal timber was donated by citizens form all the districts of the city of Bhaktapur and from other towns all over the kingdom.[29] The "siddhāgni koṭyāhuti devala pratiṣṭhā" manuscript contains the dimensions of every single timber donated by the public.[30] Apart from that, Sal timber was donated by soldiers and officials of the kingdom was well. Citizens from the all over Kingdom of Lalitpur including all the districts of the capital, Bungamati, Khokana and other cities within the kingdom donated Sal timber was well.[31]

Most of the stones for the Nyatapola temple were donated by citizens and local heads of the twenty four historical districts of the city of Bhaktapur while some were donated by the people of Thimi, Banepa, Panauti and Nagadesh.[32] Except for the one used to carved the deity, most of these stone arrived during the latter part of the construction.[32] The manuscript reports that 1528 stones were used for the construction.[32] While the dimensions of these stones were not given, it is written that it took 12–31 workers to transport the stones from the quarry to Bhaktapur.[32] The stone in which the deity housed inside was carved was brought in April 1702 by 636 workers who were paid 53 mohar and 1 dam in total.[32] The statue of the deity was entirely carved in three months by a group of thirty artisans.[32] The group was led by Tulasi Lohakarmi who received a tola of gold as a reward during the inauguration along with his wage.[32] Other sculptors who also received gold as a reward included Vishvanāth, Raksharāma, Daksharāma, Manoharasingha and Keshavarāya.[32]

The statues of two wrestlers at the lowermost plinth were carved by a group of fourteen sculptors from Lalitpur, four of whom are labelled as 'child' in the manuscript.[33] The sculptors labelled as 'child' were Krishna Raj, who worked for 37 days, Raksmidhil, who worked 28 days, Chandrasingha, who worked for 27 days and Meru, who worked for 10 days.[34] The statues of the wrestlers were carved in 40 days at most and 4 days at least.[34]

The Nyatapola temple was made with 1,135,350 bricks plus additional 102,304 bricks were used to pave the plinths.[35] Additionally, bricks were used to pave the road and courtyards in the local Tamārhi district as well.[36] For the bricks, kilns were established in December 1701 at five spots around the city gates.[29] However, most of the bricks were bought from dealers and the siddhāgni koṭyāhuti devala pratiṣṭhā manuscript contains the name of the seller and the cost of bricks purchased.[29]

From 20 February 1702, the manufacturing of the gājula (golden pinnacle placed on the top of a temple) started.[37] The gājula was manufactured by a team of 40 smiths with Navamising as their leader who received one tolā of gold as a reward during the inauguration.[37] The gājula took 99 days to manufacture and was placed on top of the temple during the inauguration day.[38]

Similarly, nyākalis or metal workers started their work of making small wind bells from 16 November 1701.[39] For the bells, Bhupatindra Malla 493 mohar for 322 kg of brass and bronze while around 107 mohar from the savings of the Taleju temple were used to buy 250 kg of brass and bronze.[39] Altogether, 529 wind bells were made; 48 were hung on the topmost roof, 80 on the second, 104 on the third, 128 on the fourth and 168 were hung on the lowermost roof.[40] Among the 529 wind bells one remained as extra which the locals called an "unlucky bell".[40]

Where the Nyatapola temple exists today, there may have been a smaller five tiered temple.[41] The temple has been referred as "ṅātapula" in the "siddhāgni koṭyāhuti devala pratiṣṭhā" manuscript.[41] Although, no other historical records of the "ṅātapula" has been found and the manuscript itself only lists the temple once when it states that "the ṅātapula was demolished in order to construct the Nyatapola".[41] In order to make space for the construction of the temple, the acquisition of houses took place in Tamārhi district. [42] The "siddhāgni koṭyāhuti devala pratiṣṭhā" manuscript does not mention these events but Dūkhi Bhāro, whose property was seized for the construction has mentioned it in his version of Ramayana that he authored.[43]

On Wednesday of the seventh day of the bright half of the month of Asadha in Nepal Sambat 824, Dūkhi Bhāro completed the Vanakānda act of the Ramayana. Dūkhi Bhāro was deeply saddened and with the aim of forgetting his sadness, wrote this book. Dūkhi's father, Gayā gifted him a house with good heart in Talamanghi district which Sri Sri Bhupatindra Malla Māhārājā acquired it in order to build the Nyatapola temple and gave him another house at Shivavāhāla in Bhōlāche district as a replacement for my previous house. After Dūkhi, his wife Sūkhū Māyā, his son Indrasing, his daughters Mahesvari and Chandesvari, his mother Basundharā and his father Gayā moved in the new house, Dūkhi's heart was not content, he was dissatisfied and saddened. Dūkhi spent his days chanting the name of Rāma and composed this Ramayana. May all be well and may Lakshmi grow more.

— Dūkhi Bhāro, Ramayana, Vanakānda[44]

There is an area in eastern part of Bhaktapur called "palikhela" meaning "land given in exchange" in Nepal Bhasa which seems to be the spot where some of the people were given houses in exchange for the acquired lands for the construction of the Nyatapola temple .[45] Dūkhi Bhāro states that he was given a new home in Bhōlāche district in the northern part of Bhaktapur but was saddened by the loss of his ancestral land and coped by authoring a Ramayana in Nepal Bhasa.[38] He directed the play in various parts of Bhaktapur.[35] Bhāro further writes that:

This Lankākānda book was finished on the Monday of the sixth day of the bright half of the month of Māgha of Nepal Sambat 821. This was written by Dūkhi Bhāro. He wrote this with the hopes of clearing sorrows in his heart; Dūkhi did not write this to exhibit his knowledge and feed his pride. There may have been some errors on the letters, there may have been some mistakes. Readers are requested to not blame the author for his mistakes but a learned person is requested to mend the errors and mistakes in the author's writing. While writing this book, Dūkhi Bhāro's sons Rudrasing and Harising, daughters Mahesvari and Chandesvari, wife Sūkhū Māyā and mother Basundharā, all seven are in sound health. Right this moment, Sri Sri Bhupatindra Malla Deva has inaugurated Jaya and Pratap and Dūkhi Bhāro has completed his book. May all be well and fortunate. May wealth grow among all. May all who chant the name of Krishna, who write the good deeds of Krishna have a sound health and happy life, and spend his after life with Narayana in happiness and not have to reincarnate.

— Dūkhi Bhāro, Ramayana, Lankākānda[46]

Starting from Thursday, 25 December 1701, around 40–69 workers were hired to first demolish the "ṅātapula" and then to dig the foundation for the Nyatapola temple.[47] It took the workers six days to demolish the ṅātapula after which the required rituals for the new temple was completed.[47] On 4 January 1702, Bhupatindra Malla inaugurated the foundation by carrying three bricks on his shoulder and laying them on the foundation thereby commencing the construction work. After the inauguration waves of people from Bhaktapur, Thimi, Sanga, Dhulikhel, Banepa, Panauti, Chaukot, Shreekhandapur and the Kingdom of Lalitpur started coming regularly to assist the construction.[20] Since the raw materials were already prepared the construction picked up pace and after two months the five level plinth had been constructed.[20] In April, as the festival Biskāh jātrā approached, construction was temporarily halted for 15 days.[21] After the festival ended, monsoon season came near. So, the construction picked up speed; citizens from all over the Nepal Mandala assisted the construction and by 7 May 1702, the lowermost floor was tiled.[48]

Siddhāgni koṭyāhuti yagya

The siddhāgni koṭyāhuti yagya was a yagya ritual where ten million oblations were offered into the yagya fire.[49] A similar ritual was performed by King Siddhi Narasingha Malla during the establishment of the temple of Krishna at Lalitpur in 1636.[50] Bhupatindra Malla had the ritual performed for the inauguration of the Nyatapola temple and the establishment of the deity inside it as well as for religious purposes like to appease the Navagraha and the Ajimā goddesses for the protection of the city.[50] The gochāya (Nepal Bhasa: 𑐐𑑂𑐰𑐕𑐵𑐫, lit. 'offering of bettlenut') ceremony denoting the yagya's start was performed on the second day of the dark half of the month of Vaisakha in Nepal Sambat 822.[50] By then the second roof from the bottom was being tiled. For the occasion, 450 full bettlenuts, 250 half-cut bettlenuts and two coconuts costing 2 mohar and 23 dam were placed in the spot of the yagya.[51] The yagya fire was lit on the ninth day of the bright half of Jyestha in Nepal Sambat 822.[52] Several gilt cooper statues of Hindu deities was consecrated for the occasion out of which a statue of a five headed Hanumāna still survives and was auctioned at Bonhams.[49] People from all over the Kathmandu Valley started coming with their musical instruments and offerings to visit the yagya.[53] As per the siddhāgni koṭyāhuti devala pratiṣṭhā manuscript, only 48 people (names given) were allowed inside the yagya including Bhupatindra Malla.[54] The manuscript also contains the details of all the religious rites performed with the yagya.[1]

Architectural elements

There are five plinths on the stairways to the entrance of the temple and each of the plinth has a pair of stone guardians. Each of the pair is said to ten times stronger than the one below them.[4] At the bottom are two Rajput wrestlers named Jai and Pratap who are said to be ten times stronger than normal men. Above them are the giant statues of two elephants and above them are the statues of two Singhas, which is a mythical big cat and can be found throughout South and Southeast Asia.[55][56] Above the cats are the statues of two Sārdūlas , a griffin-like creature of local Newari mythology.[56] And in the topmost plinths are the Tantric deities, Simhanī and Vyāghranī, the lioness and tigress deity who are the strongest of all the guardians.

There are also a total of five Ganesha idols on four shrines, one on each corner of the structure(one of the shrines, the south western one has two idols on one shrine)[8]

Siddhi Lakshmi

The temple of Nyatapola is dedicated to the Tantric deity of Siddhi Lakshmi, who is considered the ancestral deity of the Malla royal family of Bhaktapur and is also regarded as the mother deity of the Newars of Bhaktapur.[57] Carvings of the goddess can be seen all over the temple. However, as she holds the topmost position in Tantric divinity, her primary visage is kept secret from public. Only Karmāchārya priests are allowed enter the temple.[8]

The image of Siddhi Lakshmi inside the temple is said to be of immense beauty, at least 10 feet (3.048 metres) in height,[5] featuring the goddess standing with her feet on the shoulders of Bhairava—a fierce manifestation of Shiva. Siddhi Lakshmi can be seen with 9 heads and 18 arms.[58] Around the image, lie other numerous deities. It is said that her image was installed using Tantric methods, due to which, her image is hidden from the public.[8]

Cultural significance

Legend tells of the days when the Lord Bhairava, the Hindu God of destruction was causing havoc in society (1078 AD). Bhairava's temple stood in Taumadhi Square. To counteract his destructive behavior the king decided to call goddess Bhagavati, then Bhagavati took the form of Siddhi Laxmi and then carried Bhairava in her hand and built a more powerful temple on the honor of Siddhi Laxmi (Narayani Devi) in front of the Bhairab Temple. To make the brick and wood temple strong and powerful, King Bhupatindra Malla ordered guardians be placed in pairs on each level of the base leading up to the Nyatapola Temple. On the first level is a pair of likenesses of Bhaktapur's strongest man, Jaya mal Pata, a famous wrestler. Next, two elephants followed by two lions, two griffons and finally "Baghini" and "Singhini", the tiger and lion goddesses. After subduing Bhairaba, peace prevailed in the city. The Temple is the tallest temple in the Kathmandu Valley and stands 30 m high. It withstood the 1934 Nepal–Bihar earthquake.

The image of Siddhi Lakshmi is locked within the temple, and only the priests are allowed to enter to worship her. The five-storeyed temple, locally known as Nyatapola, stands in the northern side of Taumadhi Square in Bhaktapur. This is the only temple that is named after the dimension of architecture rather than from the name of the deity residing inside. The temple was erected in fewer than five months by King Bhupatindra Malla in 1701–1702 A.D.

Impact from earthquakes

The Bhairav kale survived the 2015 earthquake in spite of having the tallest shikhara in the valley. Many other temples were also damaged in the 2015 earthquake.[59][60] It had also survived the 1934 Nepal–Bihar earthquake that had damaged many other temples.[61] The ziggurat structure, and the 5 story timber and brick tower acts as a robust plinth, which allows for base isolation, separating the structure from the shaking caused by the earthquake.[62] Additionally, the use of triangulation on the roof means that any debris will fall away from the temple, rather than straight through it, as you might find in newer urban builds.

Historical Sources and records

These details were found while going into the Siddhagni Kotyahuti Devala Pratistha manuscript.[63] From the start of digging the foundation to the completion of roofing, it took merely eighty-eight days. The excavation work for foundation lasted for seven days. Then was commenced construction of six plinths. That was accomplished in thirty-one days, and immediately after that started the erection of the superstructure. That was also completed within thirty-four days, after which roofing work was started from top to the lowest roof. In sixteen days all the five roofs were completed paving them with mini-tiles (Jhingati). Then they had to wait for an auspicious day for erecting the icons in the sanctum sanctorum and fix the pinnacle on the top of the temple. For this, they did wait for 38 days. In the meantime, the fire-sacrifice (Siddhagni Kotyahuti Yajna) was going on.

Presented here are six pages (three folios) of the facsimile copies of the manuscript which recorded major events from beginning to the end, as a summary of records in advance, incorporated in the manuscript containing 264 folios. There are fifty major records in the summary six-page facsimile.

The manuscript is preserved in the National Archives of Nepal. It is readily available for readers in microfilm as well, which can be read in the office or could be purchased in photocopy paying certain rupees per page.

The name of the manuscript is recorded as Siddhagni Kotyahuti Devala Pratistha. The name itself kept the enthusiasts on the subject of ancient architecture behind the curtain from knowing it. The accession number of the manuscript is ca. I. 1115 NGMPP micro number A 249/5. The manuscript is written in the Newar script in yellow Nepalese paper coated with Harital (orpiment). The size is 17.2 x 46.5 cm. Each page has nine lines. The manuscript has 264 folios, and the rest are missing Dr. Janak Lal Vaidya thinks. Some folios are ink-stained and some are damaged by rats. All the rest of the folios are in good condition.

Out of these six facsimile pages, Dr. Janak Lal Vaidya has published three folios (1, 2 and 4) without any transliteration and translation in Abhilekh No.8 published by the National Archives of Nepal. It is, however, necessary at least to give a full picture of the detailed records in those six important pages.

There is still interesting information contained in the following folios of the manuscript which were published by Dr. Janak Lal Vaidya in his articles published in Abhilekh, No. 8 and No. 14 and Kheluita No. 11 in English, Nepali and Newar respectively.

Gallery

-

Festival

-

Wooden construction details

-

Wooden construction

-

Nyatpola & Bhairav Temples

-

Bhairav Temple from Nyatpola

-

Taumadhi Square

-

Wooden wheels of a disassembled festival cart for Bisket Jatra

-

Bhojanalaya overlooking the temples

-

Wide view of Nyatapola Temple

-

Another Side of Nyatapola Temple

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ a b Vaidya 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Dhaubhadel 2021, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e Vaidya 2004, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d "Nyatapola, the tallest pagoda of Nepal". Bhaktapur.com. 2019.

- ^ a b c Dhaubhadel 2021, pp. 33–50.

- ^ Dhaubhadel 2021, pp. 43–48.

- ^ Dhaubhadel 2021, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e Arora, Vanicka (2021). "Five Stories of Nyatapola Temple" (PDF). Our World Heritage.

- ^ Machamasi, Amit (2021). "Biska celebration begins in Bhaktpaur". Nepali Times.

- ^ Dhaubhadel 2021, p. 48.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 66.

- ^ Tuladhar, Artha Ratna (2017). Legends of Bhaktapur. Nepal. Nepal: Ratna Books. p. 4. ISBN 9789937080712.

- ^ a b Shrestha, Purushottam Lochan (1 February 2022). "भक्तपुरका असुरक्षित अभिलेख– ४". Online Majdoor. Archived from the original on 24 November 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "The Nyatapola Temple, Bhatgaon". Global Nepali Museum. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Oldfield, Henry Ambrose (1974). Sketches from Nepal, Historical and Discriptive, with an Essay on Nepalese Buddhism & Illustrations of Religions Monuments & Architecture. Cosmo Publications. p. 8.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 401.

- ^ Dhaubhadel 2021, p. 38.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 113.

- ^ a b c Dhaubhadel 2021, p. 44.

- ^ a b Dhaubhadel 2021, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Vaidya 2004, p. 80.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Vaidya 2004, p. 81.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 82.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 85.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 86.

- ^ a b c Vaidya 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 88.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vaidya 2004, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Vaidya 2004, p. 30.

- ^ a b Vaidya 2004, p. 141.

- ^ a b Dhaubhadel 2021, p. 52.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 109.

- ^ a b Vaidya 2004, p. 37.

- ^ a b Vaidya 2004, p. 38.

- ^ a b Vaidya 2004, p. 31.

- ^ a b Dhaubhadel 2021, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Vaidya 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 36.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 76.

- ^ a b Vaidya 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Dhaubhadel 2021, p. 46.

- ^ a b Buhnemann, Gudrun (June 2021). "Hanumān worship under the kings of the late Malla period in Nepal". Tantric Communities in Context. Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna: 425–468.

- ^ a b c Vaidya 2004, p. 53.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 54.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 55.

- ^ Dhaubhadel 2021, p. 47.

- ^ Vaidya 2004, p. 158.

- ^ "Singha-The Mythical Creature". Youtube. 2020. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Mythical Creatures of Nepal". OYE KTM. 2020.

- ^ "Bhaktapur's famed Nyatapola receives post-earthquake facelift". kathmandupost.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Nyatapola Jirnodwar (in Newari and Nepali). Bhaktapur: Bhaktapur Municipality. 2021. pp. 55–170. ISBN 978-9937-0-8663-9.

- ^ Just returned from Bhaktapur, Nepal: Lesson learned the hardest way, ETN NEPAL, APR 29, 2015

- ^ Man, baby rescued from rubble in Nepal, CNN, Apr 29, 2015, Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta reports from Nepal, at 1:48

- ^ Nepal earthquake: Centuries of architectural heritage gone in 80 seconds, PTI, Mid-Day, 01-May-2015

- ^ Teo, Sheilin. "Nepal's traditional seismic resistant designs". Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Research Note Work Index Of Nyatapola Temple, Contributions to Nepalese Studies, Vol. 32, NO.2 (July 2005), 267–275.

Bibliography

- Vaidya, Janaka Lāla (2004). Siddhāgni koṭyāhuti devala pratishṭhā: pān̐catale mandira/Nyātapolala Devalako nirmāṇa pratishṭhā kārya sambandhī abhilekha granthako anusandhānātmaka viśleshṇātmaka adhyayana (in Nepali). Nepāla Rājakīya Prajñā-Pratishṭhāna. ISBN 978-99933-50-99-6.

- Dhaubhadel, Om (2021). "Gaganachumbi sānskritika dharōhara ngātāpōlah". Ngātāpōlah jirnodvār (in Nepali). Bhaktapur Municipality: 33–53. ISBN 9789937086639.

- Niels Gutschow and Bernhard Kolver (1975). Bhaktapur Ordered Space Concepts and Functions in A Town of Nepal by Niels Gutschow & Bernhard Kolver. Wiesbaden. ISBN 3515020772.