| Australian involvement in the Vietnam War | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |

Australian soldiers from 7 RAR waiting to be picked up by US Army helicopters following a cordon and search operation near Phước Hải on 26 August 1967. This image is etched on the Vietnam Forces National Memorial, Canberra. | |

| Location | |

| Objective | To support South Vietnam against Communist attacks |

| Date | 31 July 1962 – 18 December 1972 |

| Executed by | Approximately 61,000 military personnel[1] |

| Casualties | 521 killed, ~3,000 wounded |

Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War began with a small commitment of 30 military advisors in 1962, and increased over the following decade to a peak of 7,672 Australian personnel following the Menzies Government's April 1965 decision to upgrade its military commitment to South Vietnam's security.[2] By the time the last Australian personnel were withdrawn in 1972, the Vietnam War had become Australia's longest war, eventually being surpassed by Australia's long-term commitment to the War in Afghanistan. It remains Australia's largest force contribution to a foreign conflict since the Second World War, and was also the most controversial military action in Australia since the conscription controversy during World War I. Although initially enjoying broad support due to concerns about the spread of communism in Southeast Asia, an increasingly influential anti-war movement developed, particularly in response to the government's imposition of conscription.

The withdrawal of Australia's forces from South Vietnam began in November 1970, under the Gorton Government, when 8 RAR completed its tour of duty and was not replaced. A phased withdrawal followed and, by 11 January 1973, Australian involvement in hostilities in Vietnam had ceased. Nevertheless, Australian troops from the Australian Embassy Platoon remained deployed in the country until 1 July 1973,[2] and Australian forces were deployed briefly in April 1975, during the fall of Saigon, to evacuate personnel from the Australian embassy. Approximately 60,000 Australians served in the war: 521 were killed and more than 3,000 were wounded.[3]

History

Background

Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War was driven largely by the rise of communism in Southeast Asia after World War II, and the fear of its spread, which developed in Australia during the 1950s and early 1960s.[4] Following the end of the World War II, the French had tried to reassert control over French Indochina, which had been occupied by Japan. In 1950, the communist-backed Việt Minh, led by Ho Chi Minh, began to gain the ascendency in the First Indochina War. In 1954, after the defeat of the French at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, the Geneva Accords of 1954 led to the splitting of the country geographically, along the 17th parallel north of latitude: the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) (recognised by the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China) ruling the north, and the State of Vietnam (SoV), an associated state in the French Union (recognised by the non-communist world) ruling the south.[5]

The Geneva Accords imposed a deadline of July 1956 for the governments of the two Vietnams to hold elections, with a view to uniting the country under one government.[6] In 1955, Ngô Đình Diệm, the prime minister of the State of Vietnam, deposed the head of state Bảo Đại in a fraudulent referendum and declared himself President of the newly proclaimed Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam).[7] He then refused to take part in the elections, claiming that the communist North Vietnam would engage in election fraud and that as a result they would win because they had more people. After the election deadline passed, the military commanders in the North began preparing an invasion of the South.[6] Over the course of the late 1950s and early 1960s this invasion took root in a campaign of insurgency, subversion and sabotage in the South employing guerrilla warfare tactics.[8] In September 1957, Diem visited Australia and was given strong support by both the ruling Liberal Party of Australia of Prime Minister Robert Menzies and the opposition Australian Labor Party (ALP). Diem was particularly feted by the Catholic community, as he pursued policies that discriminated in favour of the Catholic minority in his country and gave special powers to the Catholic Church.[9]

By 1962, the situation in South Vietnam had become so unstable that Diem submitted a request for assistance to the United States and its allies to counter the growing insurgency and the threat that it posed to South Vietnam's security. Following that, the US began to send advisors to provide tactical and logistical advice to the South Vietnamese. At the same time, the US sought to increase the legitimacy of the South Vietnamese government by instituting the Many Flags program, hoping to counter the communist propaganda that South Vietnam was merely a US puppet state,[10] and to involve as many other nations as possible. Thus Australia, as an ally of the United States, with obligations under the ANZUS Pact, and in the hope of consolidating its alliance with the US, became involved in the Vietnam War.[11] Between 1962 and 1972, Australia committed almost 60,000 personnel to Vietnam, including ground troops, naval forces and air assets, and contributed significant amounts of materiel to the war effort.[3]

Australia's military involvement

Australian advisors, 1962–1965

While assisting the British during the Malayan Emergency, Australian and New Zealand military forces had gained considerable experience in jungle warfare and counter-insurgency. According to historian Paul Ham, the US Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, "freely admitted to the ANZUS meeting in Canberra in May 1962, that the US armed forces knew little about jungle warfare".[12] Given the experience that Australian forces had gained in Malaya, it was felt that Australia could contribute in Vietnam by providing advisors who were experts in the tactics of jungle warfare. The Australian government's initial response was to send 30 military advisers, dispatched as the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV), also known as "the Team". The Australian military assistance was to be in jungle warfare training, and the Team comprised highly qualified and experienced officers and NCOs, led by Colonel Ted Serong, many with previous experience from the Malayan Emergency.[13] Their arrival in South Vietnam, during July and August 1962, was the beginning of Australia's involvement in the war in Vietnam.[14]

Relationships between the AATTV and US advisors were generally very cordial, but there were sometimes significant differences of opinion on training and tactics. For example, when Serong expressed doubt about the value of the Strategic Hamlet Program at a US Counter Insurgency Group meeting in Washington on 23 May 1963, he drew a "violent challenge" from US Marine General Victor "Brute" Krulak.[15] Captain Barry Petersen's work with raising an anti-communist Montagnard force in the Central Highlands between 1963 and 1965 highlighted another problem. South Vietnamese officials sometimes found sustained success by a foreigner difficult to accept.[16] Warrant Officer Class Two Kevin Conway, of the AATTV, was killed on 6 July 1964, side by side with Master Sergeant Gabriel Alamo of the USSF, during a sustained Vietcong (VC) attack on Nam Dong Special Forces Camp, becoming Australia's first battle casualty.[17]

Increased Australian commitment, 1965–1970

In August 1964 the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) sent a flight of Caribou transports to the port town of Vũng Tàu.[3] By the end of 1964, there were almost 200 Australian military personnel in South Vietnam, including an engineer and surgical team as well as a larger AATTV team.[18] To boost the size of the Army by providing a greater pool for infantrymen, the Australian Government had introduced conscription for compulsory military service for 20-year-olds, in November 1964, despite opposition from within the Army and many sections of the broader community.[19][20] Thereafter, battalions serving with in South Vietnam all contained National Servicemen.[21] With the war escalating the AATTV increased to approximately 100 men by December.[22]

On 29 April 1965, Menzies announced that the government had received a request for further military assistance from South Vietnam. "We have decided...in close consultation with the Government of the United States—to provide an infantry battalion for service in Vietnam." He argued that a communist victory in South Vietnam would be a direct military threat to Australia. "It must be seen as part of a thrust by Communist China between the Indian and Pacific Oceans" he added.[23]

The question of whether a formal request was made by the South Vietnamese government at that time has been disputed. Although the South Vietnamese Prime Minister, Trần Văn Hương, made a request in December 1964,[24][25] Hương's replacement, Phan Huy Quát, had to be "coerced into accepting an Australian battalion",[25] and stopped short of formally requesting the commitment in writing, simply sending an acceptance of the offer to Canberra, the day before Menzies announced it to the Australian parliament.[26] In that regard, it has been argued that the decision was made by the Australian government, against advice of the Department of Defence,[27] to coincide with the commitment of US combat troops earlier in the year, and that the decision would have been made regardless of the wishes of the South Vietnamese government.[25][28]

As a result of the announcement, the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1 RAR) was deployed. Advanced elements of the battalion departed Australia on 27 May 1965.[29] Accompanied by a troop of armoured personnel carriers from the 4th/19th Prince of Wales's Light Horse, as well as logistics personnel, they embarked upon HMAS Sydney and, following their arrival in Vietnam in June,[29] they were attached to the US 173rd Airborne Brigade, along with a Royal New Zealand Army artillery battery at Bien Hoa Base Camp.[30] Throughout 1965, they undertook several operations in Biên Hòa Province and subsequently fought significant actions, including Gang Toi, Operation Crimp and Suoi Bong Trang.[31] Meanwhile, 1 RAR's attachment to US forces had highlighted the differences between Australian and American operational methods,[32][33] and Australian and US military leaders subsequently agreed that Australian combat forces should be deployed in a discrete province. That would allow the Australian Army to "fight their own tactical war", independently of the US.[34]

In April 1966, 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF) was established in Phước Tuy Province, based at Nui Dat. 1 ATF consisted of two (and, after 1967, three) infantry battalions, a troop, and later a squadron, of armoured personnel carriers from the 1st Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, and a detachment of the Special Air Service Regiment (SASR), as well as support services under the command of the 1st Australian Logistic Support Group (1 ALSG), based in Vũng Tàu. A squadron of Centurion tanks was added in December 1967. The New Zealand battery and a battery from the U.S 35th Field Artillery Regiment were integrated into the task force. New Zealand infantry units were deployed in 1967 and, after March 1968, were integrated into Australian battalions serving with 1 ATF. The combined infantry forces were thereafter designated "ANZAC Battalions".[2] Special forces from the New Zealand Special Air Service were also attached to each Australian SASR squadron from late 1968.[35] 1 ATF's responsibility was the security of Phước Tuy Province, excluding larger towns.[2]

The RAAF contingent was also expanded, growing to include three squadrons — No. 35 Squadron, flying Caribous, No. 9 Squadron flying UH-1 Iroquois battlefield helicopters and No. 2 Squadron flying Canberra bombers. Based at Phan Rang Air Base in Ninh Thuận Province, the Canberras flew many bombing sorties, and two were lost, while the Caribou transport aircraft supported anti-communist ground forces, and the Iroquois helicopters were used in troop-lifts and medical evacuation and, from Vũng Tàu Air Base, as gunships in support of 1 ATF. At its peak it included over 750 personnel.[36]

During the war, RAAF CAC-27 Sabre fighters from No. 79 Squadron were deployed to Ubon Air Base in Thailand as part of Australia's SEATO commitments. The Sabres took no part in direct hostilities against North Vietnam, and were withdrawn in 1968.[37] The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) also made a significant contribution, which involved the deployment of one destroyer, on six-month rotations, deployed on the gun-line in a shore bombardment role. The RAN Helicopter Flight Vietnam and a RAN Clearance Diving Team were also deployed. The ageing aircraft carrier, HMAS Sydney, after being converted to a troop-ship, was used to convey the bulk of Australian ground forces to South Vietnam.[38] Female members of the Army and RAAF nursing services were present in Vietnam from the outset and, as the force grew, the medical capability was expanded by the establishment of the 1st Australian Field Hospital at Vũng Tàu on 1 April 1968.[39]

From an Australian perspective, the most famous engagement in the war was the Battle of Long Tan, which took place on 18 and 19 August 1966. During the battle, a company from 6 RAR, despite being heavily outnumbered, fought off an assault by a force of regimental strength. 18 Australians were killed and 24 wounded, while at least 245 VC were killed. It was a decisive Australian victory and is often cited as an example of the importance of combining and coordinating infantry, artillery, armour and military aviation. The battle had considerable tactical implications as well, being significant in allowing the Australians to gain dominance over Phước Tuy Province and, although there were other large-scale encounters in later years, 1 ATF was not fundamentally challenged again.[40] Regardless, during February 1967, 1 ATF sustained its heaviest casualties in the war to that point, losing 16 men killed and 55 wounded in a single week, the bulk of them during Operation Bribie. 1 ATF appeared to have lost the initiative and, for the first time in nine months of operations, the number of Australians killed in battle, or from friendly fire, mines or booby traps, had reversed the task force's kill ratio.[41]

Such losses underscored the need for a third battalion, and the requirement for tanks to support the infantry, a realisation which challenged the conventional wisdom of Australian counter-revolutionary warfare doctrine, which had previously allotted only a minor role to armour. Yet, it was nearly a year before more Australian forces finally arrived.[42] To Brigadier Stuart Graham, the 1 ATF commander, Operation Bribie confirmed the need to establish a physical barrier, to deny the VC freedom of movement and thereby regain the initiative. The subsequent decision to establish an 11-kilometre (6.8 mi) barrier minefield from Đất Đỏ to the coast increasingly came to dominate task force planning. Ultimately, that would prove both controversial and costly for the Australians. Despite initial success, the minefield became a source of munitions for the VC to use against 1 ATF and, in 1969, the decision was made to remove it.[43][44]

As the war continued to escalate following further American troop increases, 1 ATF was heavily reinforced in late 1967. A third infantry battalion arrived in December 1967, and a squadron of Centurion tanks, and more Iroquois helicopters, were added in early 1968. In all, a further 1,200 men were deployed, taking the total Australian troop strength to over 8,000 men, its highest level during the war. This increase effectively doubled the combat power available to the task force commander.[45]

Although primarily operating out of Phước Tuy, the 1 ATF was also available for deployment elsewhere in the III Corps Tactical Zone. As Phước Tuy progressively came under Australian control, 1968 saw the Australians spending a significant period of time conducting operations further afield. The communist Tet Offensive began on 30 January 1968 with the aim of inciting a general uprising, simultaneously engulfing population centres across South Vietnam. In response, 1 ATF was deployed along likely infiltration routes to defend the vital Biên Hòa–Long Binh complex northeast of Saigon, as part of Operation Coburg between January and March. Heavy fighting resulted in 17 Australians being killed and 61 wounded, while communist casualties included at least 145 killed, 110 wounded and 5 captured, with many more removed from the battlefield.[46] Tet also affected Phước Tuy Province and, although stretched thin, the remaining Australian forces there successfully repelled an attack on Ba Ria, as well as spoiling a harassing attack on Long Dien. A sweep of Hỏa Lòng was conducted, killing 50 VC and wounding 25, for the loss of five Australians killed and 24 wounded.[47] In late February, the communist offensive collapsed, suffering more than 45,000 killed, compared with allied losses of 6,000 men.[48][49] Regardless, Tet proved to be a turning point in the war and, although it was a tactical disaster for the communists, it proved a strategic victory for them. Confidence in the American military and political leadership collapsed, as did public support for the war in the United States.[50]

Tet had a similar effect on Australian public opinion, and caused growing uncertainty in the government about the determination of the United States to remain militarily involved in Southeast Asia.[51] Amid the initial shock, Prime Minister John Gorton unexpectedly declared that Australia would not increase its military commitment in Vietnam.[52] The war continued without respite and, between May and June 1968, 1 ATF was again deployed away from Phước Tuy in response to intelligence reports of another impending offensive. In May 1968, 1 RAR and 3 RAR, with armour and artillery, support fought off large-scale attacks during the Battle of Coral–Balmoral. 25 Australians were killed and nearly 100 wounded, while the North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) lost in excess of 300 killed.[40]

Later, from December 1968 to February 1969, two battalions from 1 ATF again deployed away from their base in Phước Tuy province, operating against suspected PAVN/VC bases in the Hat Dich area, in western Phước Tuy, south-eastern Biên Hòa, and south-western Long Khan provinces, during Operation Goodwood.[53] The fighting lasted 78 days and was one of the longest out-of-province operations mounted by the Australians during the war.[54][55]

From May 1969, the main effort of the task force refocussed on Phước Tuy Province.[56] Later in June 1969, 5 RAR fought one of the last large-scale actions of the Australian involvement in the war, during the Battle of Binh Ba, 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) north of Nui Dat in Phước Tuy Province. The battle differed from the unusual Australian experience, because it involved infantry and armour in close-quarter house-to-house fighting against a combined PAVN/VC force, through the village of Binh Ba. For the loss of one Australian killed, the PAVN/VC lost 107 killed, six wounded and eight captured, in a hard-fought but one-sided engagement.[57]

Due to the losses suffered at Binh Ba, the PAVN was forced to move out of Phước Tuy into adjoining provinces and, although the Australians did encounter main force units in the years to come, the Battle of Binh Ba marked the end of such clashes.[59] Yet, while the VC had largely been forced to withdraw to the borders of the province by 1968–69, control of Phước Tuy was challenged on several occasions in the following years, including during the 1968 Tet Offensive, as well as in mid-1969, following the incursion of the PAVN 33rd Regiment, and again in mid-1971, with further incursions by the 33rd Regiment and several VC main force units and, finally, during the Easter Offensive in 1972. Attacks on South Vietnamese Regional Force outposts, and incursions into the villages, had also continued.[60]

Large-scale battles were not the norm in Phước Tuy Province. More typical was company-level patrolling and cordon and search operations, which were designed to put pressure on enemy units and disrupt their access to the local population. To the end of Australian operations in Phước Tuy, that remained the focus of Australian efforts, and that approach arguably achieved the restoration of South Vietnamese government control in the province.[61] Australia's peak commitment at any one time was 7,672 combat troops and New Zealand's, 552, in 1969.[2]

During that time, the AATTV had continued to operate in support of the South Vietnamese forces, with an area of operations stretching from the far south to the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) which formed the border between North Vietnam and South Vietnam. Members of the team were involved in many combat operations, often commanding formations of Vietnamese soldiers. Some advisors worked with regular Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) units and formations, while others worked with the Montagnard hill tribes, in conjunction with US Special Forces. A few were involved in the controversial Phoenix Program, run by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which was designed to target the VC infrastructure through infiltration, arrest and assassination. The AATTV became Australia's most decorated unit of the war, winning all four Victoria Crosses awarded during the conflict.[22]

Australia also sent some civilian medical staff to help during the war.[62] 43 Australian army nurses served.[63][64]

Australian counter-insurgency tactics and civic action

Historian Albert Palazzo comments that when the Australians entered the Vietnam War, it was with their own "well considered ...concept of war", and this was often contradictory or in conflict with US concepts.[65] The 1 ATF light infantry tactics such as patrolling, searching villages without destroying them (with a view to eventually converting them), and ambush and counter ambush drew criticism from some US commanders. General William Westmoreland is reported to have complained to Major General Tim Vincent that 1 ATF was "not being aggressive enough".[66] By comparison, US forces sought to flush out the enemy and achieve rapid and decisive victory through "brazen scrub bashing" and the use of "massive firepower."[67] Australians acknowledged they had much to learn from the US forces about heliborne assault and joint armour and infantry assaults. Yet the US measure of success—the body count—was apparently held in contempt by many 1 ATF battalion commanders.[68]

In 1966, journalist Gerald Stone described tactics then being used by Australian soldiers newly arrived in Vietnam:

The Australian battalion has been described ...as the safest combat force in Vietnam... It is widely felt that the Australians have shown themselves able to give chase to the guerrillas without exposing themselves to the lethal ambushes that have claimed so many American dead... Australian patrols shun jungle tracks and clearings... picking their way carefully and quietly through bamboo thickets and tangled foliage... .It is a frustrating experience to trek through the jungle with Australians. Patrols have taken as much as nine hours to sweep a mile of terrain. They move forward a few steps at a time, stop, listen, then proceed again.[69]

Looking back on ten years of reporting the war in Vietnam and Cambodia, journalist Neil Davis said in 1983: "I was very proud of the Australian troops. They were very professional, very well trained and they fought the people they were sent to fight—the Viet Cong. They tried not to involve civilians and generally there were fewer casualties inflicted by the Australians."[70] Another perspective on Australian operations was provided by David Hackworth: "The Aussies used squads to make contact... and brought in reinforcements to do the killing; they planned in the belief that a platoon on the battlefield could do anything."[71]

For some VC leaders there was no doubt the Australian jungle warfare approach was effective. One former VC leader is quoted as saying: "worse than the Americans were the Australians. The Americans style was to hit us, then call for planes and artillery. Our response was to break contact and disappear if we could...The Australians were more patient than the Americans, better guerrilla fighters, better at ambushes. They liked to stay with us instead of calling in the planes. We were more afraid of their style."[72] According to Albert Palazzo, as a junior partner, the Australians had little opportunity to influence US strategy in the war: "the American concept [of how the war should be fought] remained unchallenged and it prevailed almost by default."[73]

Overall, the operational strategy used by the Australian Army in Vietnam was not successful. Palazzo believes that like the Americans, Australian strategy was focused on seeking to engage the PAVN/VC forces in battle and ultimately failed as the PAVN/VC were generally able to evade Australian forces when conditions were not favourable. Moreover, the Australians did not devote sufficient resources to disrupting the logistical infrastructure which supported the PAVN/VC forces in Phước Tuy Province and popular support for them remained strong. After 1 ATF was withdrawn in 1971 the insurgency in Phước Tuy rapidly expanded.[74]

Historians Andrew Ross, Robert Hall, and Amy Griffin, on the other hand make the point that Australian forces more often than not defeated the PAVN/VC whenever they met them, nine times out of ten. When the Australians were able to set ambushes, or openly engage the enemy, they defeated them and killed or destroyed the units that opposed them.[75]

Meanwhile, although the bulk of Australian military resources in Vietnam were devoted to operations against the PAVN/VC forces, a civic action program was also undertaken to assist the local population and government authorities in Phước Tuy. This included projects aimed at winning the support of the people and was seen as an essential element of Australian counter-revolutionary doctrine.[76] Australian forces had first undertaken some civic action projects in 1965 while 1 RAR was operating in Biên Hòa, and similar work was started in Phước Tuy following the deployment of 1 ATF in 1966.[77] In June 1967 the 40-man 1st Australian Civil Affairs Unit (1 ACAU) was established to undertake the program.[78] By 1970 this unit had grown to 55 men, with detachments specialising in engineering, medical, education and agriculture.[77]

During the first three years of the Australian presence civic action was mainly an adjunct to military operations, the unit taking part in the cordon and search of villages and resettlement programs, as well as occasionally in directly aiding and reconstructing villages that had been damaged in major actions. In the final years of the Australian presence it became more involved in assistance to villages and to the provincial administration. While 1 ACAU was the main agency involved in such tasks, at times other task force units were also involved in civic action programs. Activities included construction and public works, medical and dental treatment, education, agriculture development and youth and sports programs.[79]

Although extensive, these programs were often undertaken without reference to the local population and it was not until 1969 that villagers were involved in determining what projects would be undertaken and in their construction. Equally, ongoing staff and material support was usually not provided, while maintenance and sustainment was the responsibility of the provincial government which often lacked the capacity or the will to provide it, limiting the benefit provided to the local population.[78] The program continued until 1 ATF's withdrawal in 1971, and although it may have succeeded in generating goodwill towards Australian forces, it largely failed to increase support for the South Vietnamese government in the province. Equally, while the program made some useful contributions to the civil facilities and infrastructure in Phước Tuy which remained following the Australian departure, it had little impact on the course of the conflict.[80]

Withdrawal of Australian forces, 1970–1973

The Australian withdrawal effectively commenced in November 1970. As a consequence of the overall US strategy of Vietnamization and with the Australian government keen to reduce its own commitment to the war, 8 RAR was not replaced at the end of its tour of duty. 1 ATF was again reduced to just two infantry battalions, albeit with significant armour, artillery and aviation support remaining.[81] The Australian area of operations remained the same, the reduction in forces only adding further to the burden on the remaining battalions.[81] Regardless, following a sustained effort by 1 ATF in Phước Tuy Province between September 1969 and April 1970, the bulk of PAVN/VC forces had become inactive and had left the province to recuperate.[82] By 1971 the province had been largely cleared of local VC forces, who were now increasingly reliant on reinforcements from North Vietnam. As a measure of some success, Highway 15, the main route running through Phước Tuy between Saigon and Vũng Tàu, was open to unescorted traffic. Regardless, the VC maintained the ability to conduct local operations.[61] Meanwhile, the AATTV had been further expanded, and a Jungle Warfare Training Centre was established in Phước Tuy Province first at Nui Dat then relocated to Van Kiep.[83] In November 1970, the unit's strength peaked at 227 advisors.[84][85]

Australian combat forces were further reduced during 1971.[2] The Battle of Long Khánh on 6–7 June 1971 took place during one of the last major joint US-Australian operations, and resulted in three Australians killed and six wounded during heavy fighting in which an RAAF UH-1H Iroqouis was shot down.[86] On 18 August 1971, Australia and New Zealand decided to withdraw their troops from Vietnam; the Australian prime minister, William McMahon, announced that 1 ATF would cease operations in October, commencing a phased withdrawal.[87][88] The Battle of Nui Le on 21 September proved to be the last major battle fought by Australian forces in the war, and resulted in five Australians killed and 30 wounded.[89] Finally, on 16 October Australian forces handed over control of the base at Nui Dat to South Vietnamese forces, while the main body from 4 RAR—the last Australian infantry battalion in South Vietnam—sailed for Australia on board HMAS Sydney on 9 December 1971.[90] Meanwhile, D Company, 4 RAR with an assault pioneer and mortar section and a detachment of APCs remained in Vũng Tàu to protect the task force headquarters and 1 ALSG until the final withdrawal of stores and equipment could be completed, finally returning to Australia on 12 March 1972.[91]

Australian advisors continued to train Vietnamese troops until the announcement by the newly elected Australian Labor government of Gough Whitlam that the remaining advisors would be withdrawn by 18 December 1972. It was only on 11 January 1973 that the Governor-General of Australia, Paul Hasluck, announced the cessation of combat operations.[2] Whitlam recognised North Vietnam, which welcomed his electoral success.[92] Australian troops remained in Saigon guarding the Australian embassy until 1 July 1973.[2] The withdrawal from South Vietnam meant that 1973 was the first time since the beginning of World War II in 1939 that Australia's armed forces were not involved in a conflict somewhere in the world.[2] In total approximately 60,000 Australians—ground troops, air-force and naval personnel—served in South Vietnam between 1962 and 1972. 521 died as a result of the war and over 3,000 were wounded.[3] 15,381 conscripted national servicemen served from 1965 to 1972, sustaining 202 killed and 1,279 wounded.[93] Six Australians were listed as missing in action, although these men are included in the list of Australians killed in action and the last of their remains were finally located and returned to Australia in 2009.[94][95] Between 1962 and March 1972 the estimated cost of Australia's involvement in the war was $218.4 million.[96]

In March 1975 the Australian Government dispatched RAAF transport aircraft to South Vietnam to provide humanitarian assistance to refugees fleeing the North Vietnamese Ho Chi Minh Campaign. The first Australian C-130 Hercules arrived at Tan Son Nhat Airport on 30 March and the force, which was designated 'Detachment S', reached a strength of eight Hercules by the second week of April. The aircraft of detachment S transported refugees from cities near the front line and evacuated Australians and several hundred Vietnamese orphans from Saigon to Malaysia. They also regularly flew supplies to a large refugee camp at An Thoi on the island of Phú Quốc.[97] The deteriorating security situation forced the Australian aircraft to be withdrawn to Bangkok in mid-April, from where they flew into South Vietnam each day. The last three RAAF flights into Saigon took place on 25 April, when the Australian embassy was evacuated. While all Australians were evacuated, 130 South Vietnamese who had worked at the embassy and had been promised evacuation were left behind.[98] Whitlam later refused to accept South Vietnamese refugees following the fall of Saigon in April 1975, including Australian embassy staff who were later sent to re-education camps by the communists.[99] The Liberals—led by Malcolm Fraser—condemned Whitlam,[100] and after defeating Labor in the 1975 federal election, allowed South Vietnamese refugees to settle in Australia in large numbers.[101]

Protests against the war

In Australia, resistance to the war was at first very limited. Initially public opinion was strongly in support of government policy in Vietnam and when the leader of the ALP (in opposition for most of the period), Arthur Calwell announced that the 1966 federal election would be fought specifically on the issue of Vietnam the party suffered its biggest political defeat in decades.[102] Anti-war sentiment escalated rapidly from 1967,[103] although it never gained support from the majority of the Australian community.[104] The centre-left ALP became more sympathetic to the communists and Calwell stridently denounced South Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyễn Cao Kỳ as a "fascist dictator" and a "butcher" ahead of his 1967 visit[105]—at the time Ky was the chief of the Republic of Vietnam Air Force and headed a military junta. Despite the controversy leading up to the visit, Ky's trip was a success. He dealt with the media effectively, despite hostile sentiment from some sections of the press and public.[106] After hostile questioning from Tribune journalist Harry Stein, Ky personally offered Stein space on his own flight to visit South Vietnam for himself.[107]

-

Anti-Vietnam War demonstration Martin Place to Garden Island Dock, Sydney, 1966

-

Police officers and protestors, 1966

-

1966 protest: one sign reads, "Was Anti-Semitism an Excuse for Hitler - Is Anti-Communism An Excuse for Murder?"

-

Anti-Vietnam War demonstration at Phillip Street Court, Sydney, 1968

The introduction of conscription by the Australian government in response to a worsening regional strategic outlook during the war was consistently opposed by the ALP and by many sections of society, and some groups resisted the call to military service by burning the letters notifying them of their conscription, which was punishable by a monetary fine, or incited young men to refrain from registering for the draft, which was punishable by imprisonment.[108] Growing public uneasiness about the death toll was fuelled by a series of highly publicised arrests of conscientious objectors, and exacerbated by revelations of atrocities committed against Vietnamese civilians, leading to a rapid increase in domestic opposition to the war between 1967 and 1970.[109] Following the 1969 federal election, which Labor lost again but with a much reduced margin, public debate about Vietnam was increasingly dominated by those opposed to government policy.[110] On 8 May 1970, moratorium marches were held in major Australian cities to coincide with the marches in the US. The demonstration in Melbourne, led by future deputy prime minister Jim Cairns, was supported by an estimated 100,000 people.[111] Across Australia, it was estimated that 200,000 people were involved.[3]

Nevertheless, opinion polls taken at the time demonstrated that the moratorium failed to achieve its goals and had only a very limited impact upon public opinion, over half the respondents saying that they still supported national service and slightly less stating that they did not want Australia to pull out of the war.[112] The numbers that resisted the draft remained low. Indeed, by 1970 it was estimated that 99.8 per cent of those issued with call up papers complied with them.[113]

Further moratoria were undertaken on 18 September 1970 and again on 30 June 1971. Arguably, the peace movement had lost its original spirit, as the political debate degenerated, according to author Paul Ham, towards "menace and violence".[114] Dominated by elements Ham describes as "left-wing extremists", the organisers of the events extended invitations to members of the North Vietnamese government to attend, although this was prevented by the Australian government's refusing to grant them visas. Attendance at the subsequent marches was lower than that of May 1970, and as a result of several factors including confusion over the rules regarding what the protesters were allowed to do, aggressive police tactics, and agitation from protesters, the second march became violent.[115] In Sydney, 173 people were arrested, while in Melbourne the police attempted to control the crowd with a baton-charge.[115]

Social attitudes and treatment of veterans

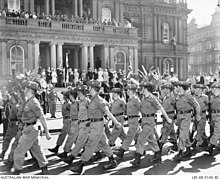

Initially there was considerable support for Australia's involvement in Vietnam, and all Australian battalions returning from Vietnam participated in well attended welcome home parades through either Sydney, Adelaide, Brisbane or Townsville, even during the early 1970s.[116] Regardless, as opposition to the war increased service in Vietnam came to be seen by sections of the Australian community in less than sympathetic terms and opposition to it generated negative views of veterans in some quarters. In the years following the war, some Vietnam veterans experienced social exclusion and problems readjusting to society. Nevertheless, as the tour of duty of each soldier during the Vietnam War was limited to one year (although some soldiers chose to sign up for a second or even a third tour of duty), the number of soldiers suffering from combat stress was probably more limited than it might otherwise have been.[117]

As well as the negative sentiments towards returned soldiers from some sections of the anti-war movement, some Second World War veterans also held negative views of the Vietnam War veterans. As a result, many Australian Vietnam veterans were excluded from joining the Returned Servicemen's League (RSL) during the 1960s and 1970s on the grounds that the Vietnam War veterans did not fight a "real war".[118] The response of the RSL varied across the country, and while some rejected Vietnam veterans, other branches, particularly those in rural areas, were said to be very supportive.[118] Many Vietnam veterans were excluded from marching in Anzac Day parades during the 1970s because some soldiers of earlier wars saw the Vietnam veterans as unworthy heirs to the ANZAC title and tradition, a view that hurt many Vietnam veterans and resulted in continued resentment towards the RSL.[118] In 1972 the RSL decided that Vietnam veterans should lead the march, which attracted large crowds throughout the country.[119]

Australian Vietnam veterans were honoured at a "Welcome Home" parade in Sydney on 3 October 1987, and it was then that a campaign for the construction of the Vietnam War Memorial began.[120] This memorial, known as the Vietnam Forces National Memorial, was established on Anzac Parade in Canberra, and was dedicated on 3 October 1992.[121]

Effect on Australian foreign and defence policy

In the aftermath of the Vietnam War the withdrawal of the US from South-East Asia forced Australia to adopt a more independent foreign policy, moving away from forward defence and reliance on powerful allies to a greater emphasis on the defence of continental Australia and military self-reliance, albeit in the context of a continued alliance with the United States. This later had important implications for the military's force structure in the 1980s and 1990s.[122] The experience in Vietnam also caused an intolerance for casualties which resulted in successive Australian governments becoming more cautious towards the deployment of military forces overseas.[123] Regardless, the "imperative to deploy forces overseas" remained a feature of Australian strategic behaviour in the post-Vietnam era,[124] while the US alliance has continued to be a fundamental aspect of its foreign policy into the early 21st century.[125] A major difference in the wars since Vietnam where Australians have been sent to fight by their government (with no prior parliamentary vote)[126][127] is that no personnel were conscripted.[128]

Timeline

| 1950 |

|

| 1957 |

|

| 1962 |

|

| 1963 |

|

| 1964 |

|

| 1965 |

|

| 1966 |

|

| 1967 |

|

| 1968 |

|

| 1969 |

|

| 1970 |

|

| 1971 |

|

| 1972 |

|

In Australian popular culture

- Khe Sanh (song, 1978) Song by Cold Chisel, sung by Jimmy Barnes, writtten by Don Walker, speaking of veterans' alienation from, and rejection by, the Australian community who had sent them to fight.

- I was only 19 (song, 1983). Sung by Redgum, written by John Schumann, and asserted to have been influential in the reintegration of Australian Vietnam vets and their acceptance into society.[149][150]

- The odd angry shot (film, 1979) (where an Australian Vietnam vet responds "no" to the question as to whether he fought in Vietnam)

- the odd angry shot (novel, 1975)

Note that all the cultural items above appeared prior to 1987, the year of the "Welcome Home" parade in Sydney[120] and formed part of the process of acceptance back into the Australian community of Vietnam veterans.

See also

- Australian Army battle honours of the Vietnam War

- Canada and the Vietnam War

- History of the Australian Army

- Military History of Australia

- New Zealand in the Vietnam War

- Order of battle of Australian forces during the Vietnam War

- Role of United States in the Vietnam War

- South Korea in the Vietnam War

Notes

- ^ "About this Nominal Roll". Nominal Roll of Vietnam Veterans. Department of Veterans' Affairs. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Vietnam War 1962–1972". Website. Army History Unit. Archived from the original on 5 September 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "Vietnam War 1962–1972". Encyclopaedia. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 1 July 2006.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 42.

- ^ a b Ham 2007, p. 59.

- ^ Nalty 1998, p. 8.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 59–71.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 57.

- ^ McNeill 1984, p. 4.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 236.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 91.

- ^ McNeill 1984, p. 6.

- ^ As a point of comparison, there were 16,000 US advisors in Vietnam at the same time.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 93–94.

- ^ McNeill 1984, p. 67.

- ^ "Vietnam—Australia's Longest War: A Calendar of Military and Political Events". Vietnam Veterans Association of Australia. 2006. Retrieved 1 July 2006.

- ^ Harpur 1990, p. 98.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 166–172.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 238.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 175.

- ^ a b Dennis et al 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 118–119

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 237.

- ^ a b c Ham 2007, p. 121.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 123.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Andrew 1975, pp. 172–173.

- ^ a b Ham 2007, p. 128.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 131.

- ^ Dennis et al 2008, p. 555.

- ^ Kuring 2004, pp. 321–322

- ^ McNeill 1993, pp. 171–172

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 179.

- ^ Crosby 2009, p. 195

- ^ Dennis 1995, p. 510.

- ^ Stephens 2006, pp. 254–257.

- ^ Dennis 1995, p. 519.

- ^ O'Keefe 1994, p. 135.

- ^ a b Dennis 1995, p. 619.

- ^ McNeill and Ekins 2003, p. 126.

- ^ McNeill and Ekins 2003, p. 269.

- ^ McNeill and Ekins 2003, pp. 126–128.

- ^ Palazzo 2006, pp. 79–83.

- ^ McNeill and Ekins 2003, p. 249.

- ^ McNeill and Ekins 2003, p. 303.

- ^ McNeill and Ekins 2003, pp. 308–310.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 345.

- ^ McNeill and Ekins 2003, p. 311.

- ^ McNeill and Ekins 2003, p. 310.

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 193.

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 196.

- ^ Ekins and McNeill 2012, p. 727.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 477–478.

- ^ Horner 1990, pp. 457–459.

- ^ Frost 1987, p. 118.

- ^ McKay and Nicholas 2001, p. 212.

- ^ Dapin, Mark (26 October 2014). "Memories of Australia's part in the Vietnam War are clouded by myth". Herald Sun. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 290.

- ^ Ekins & McNeill 2012, p.692.

- ^ a b Dennis 1995, p. 620.

- ^ "Nurses: Australian Surgical Team, South Australian staff, Bien Hoa Provincial Hospital". Health Museum of South Australia. Retrieved 12 January 2022 – via eHive.

- ^ Brayley, Annabelle (2017). Our Vietnam Nurses. Melbourne: Penguin Random House. ISBN 9780143785798.

- ^ Biedermann, Narelle (2004). Tears on My Pillow: Australian nurses in Vietnam. Milsons Point: Random House. ISBN 9781740511995.

- ^ Palazzo 2006, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 316.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 418.

- ^ Stone 1966, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Neil Davis, quoted in Bowden 1987, p. 143.

- ^ Hackworth & Sherman 1989, p. 495.

- ^ Chanoff and To.ai 1996, p. 108.

- ^ Palazzo 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Palazzo 2006, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Ross, Hall & Griffin, p.255

- ^ Frost 1987, p. 61.

- ^ a b Frost 1987, p. 166.

- ^ a b Palazzo 2006, p. 116.

- ^ Frost 1987, pp. 166–168.

- ^ Frost 1987, pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b Horner 2008, p. 231.

- ^ Horner 2008, p. 232.

- ^ Lyles 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Hartley 2002, p. 244.

- ^ Guest and McNeill 1992, p. xiii.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 2001, pp. 291–292.

- ^ a b Horner 2008, p. 233.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 551–552.

- ^ a b Odgers 1988, p. 246.

- ^ a b c Odgers 1988, p. 247.

- ^ Ekins and McNeill 2012, pp. 640–641.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 317–320, 325–326.

- ^ "National Service Scheme". Encyclopaedia. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 1 July 2006.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 649–650.

- ^ Blenkin, Max (30 August 2009). "Last Aussie Vietnam War soldiers coming home". News.com.au. News Limited. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Ekins, Ashley. "Impressions: Australians in Vietnam. Overview of Australian military involvement in the Vietnam War, 1962–1975". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1995, pp. 322–326.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1995, pp. 329–331.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 332–335.

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 336.

- ^ Jupp 2001, pp. 723–724, 732–733.

- ^ Dennis et al 2008, p. 557.

- ^ Edwards 2014, p. 162

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 248.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 143–146.

- ^ Deery, Phillip (1 November 2015). ""Lock up Holt, Throw away Ky": The Visit to Australia of Prime Minister Ky, 1967". Labour History. 109 (1): 55–75. doi:10.5263/labourhistory.109.0055. ISSN 1839-3039.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 271, 335, 458 & 528.

- ^ Ham 2007, pp. 449–461.

- ^ Dennis et al 2008, p. 558.

- ^ The Australian, 9 May 1970, estimated the crowd as 100,000. Also Strangio, Paul (13 October 2003). "Farewell to a conscience of the nation". The Age. Retrieved 1 July 2006.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 526.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 527.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 528.

- ^ a b Ham 2007, p. 529.

- ^ Woodruff 1999, p. 230.

- ^ Pols, Hans. "War, Trauma, and Psychiatry". HPS (History and Philosophy of Science) in the Science Alliance Newsletter. The University of Sydney—History and Philosophy of Science. Archived from the original on 22 November 2005. Retrieved 1 July 2006.

- ^ a b c Ham 2007, p. 565.

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 307.

- ^ a b Ham 2007, p. 650.

- ^ Fontana, Shane (1995). "Dedication of the Australian Vietnam Forces National Memorial in Canberra". Vietnam Veterans. Bill McBride. Archived from the original on 16 June 2006. Retrieved 2 July 2006.

- ^ Edwards 2014, pp. 261–264.

- ^ Blaxland 2014, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Blaxland 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Edwards 2014, pp. 265–268.

- ^ "Fact check: Who has a say in sending Australian troops to war?". ABC News. 8 September 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ "The Australian parliament must have the power to decide if we go to war | Australian Greens". greens.org.au. 20 July 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ "The Big Question: should Australia consider bringing back conscription?". stories.uq.edu.au. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Edwards 1991, p. 17.

- ^ Hartley 2002, p. 240.

- ^ "Australian Army Training Team Vietnam". Australian military units. Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ Caufield 2007, p. 80.

- ^ Hartley 2002, p. 242.

- ^ "Chronology" (PDF). Impressions:Australians in Vietnam. Australian War Memorial. 1997. Retrieved 3 July 2006.

- ^ "In for the long haul: 40th Anniversary of the First Air Force Deployment to Vietnam". Air Force News. Royal Australian Air Force. 2004. Retrieved 3 July 2006.

- ^ Caufield 2007, p. 101.

- ^ Caufield 2007, p. 87.

- ^ Caufield 2007, p. 89.

- ^ Caufield 2007, pp. 357–358.

- ^ Coulhard-Clark 2001, p. 286.

- ^ "Hyland, Charles Keith (1914–1989)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 2007.

- ^ McAulay 1988, p. 338.

- ^ a b Rayner, Michelle (2002). "Warnes, Catherine Anne (1949–1969)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. p. 496. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 525.

- ^ Markey, Ray (1998). "In Praise of Protest: The Vietnam Moratorium" (PDF). Illawarra Unity. Illawarra Branch of the Australian Society for the Study of Labour History; University of Wollongong. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2006. Retrieved 3 July 2006.

- ^ Freudenberg 2009, p. 247.

- ^ 'History maker turns historian' Adelaide Advertiser, 16 January 1988, p. 2

- ^ Interview with Robert Martin [sound recording], Peter Donovan, 1989 Adelaide Gaol Oral History Project State Library of South Australia

- ^ Simon Owens (25 April 1989). Interview - "Frankie" from I was only 19 - John Schuman, Frank Hunt with Bert Newton. Retrieved 1 January 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ Sky News Australia (25 April 2023). ‘I’m very proud of it’: John Schumann reflects on his song ‘I Was Only 19’. Retrieved 1 January 2025 – via YouTube.

References

- Andrews, E.M (1975). A History of Australian Foreign Policy. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. ISBN 0582682533.

- Blaxland, John (2014). The Australian Army from Whitlam to Howard. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107043657.

- Bowden, Tim (1987). One Crowded Hour. Sydney: Collins Australia. ISBN 0-00-217496-0.

- Caufield, Michael (2007). The Vietnam Years: From the Jungle to the Australian Suburbs. Sydney, New South Wales: Hachette Australia. ISBN 9780733619854.

- Chanoff, David; Doan Van Toai (1996). Vietnam, A Portrait of its People at War. London: Taurus & Co. ISBN 1-86064-076-1.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1995). The RAAF in Vietnam. Australian Air Involvement in the Vietnam War 1962–1975. The Official History of Australia's Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1975. Vol. Four. Sydney: Allen & Unwin in association with the Australian War Memorial. ISBN 1-86373-305-1.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (First ed.). St Leonards: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (2001). The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (Second ed.). Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-634-7.

- Crosby, Ron (2009). NZSAS: The First Fifty Years. Auckland: Viking. ISBN 978-0-67-007424-2.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin (1995). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (First ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553227-9.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin; Bou, Jean (2008). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (Second ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Edwards, Peter. "Australian Government and the Involvement in the Vietnam War". Vietnam Generation. 3 (2): 16–25.

- Edwards, Peter (1992). Crises and Commitments: The Politics and Diplomacy of Australia's Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1965. The Official History of Australia's Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1975. Vol. One. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86373-184-9.

- Edwards, Peter (1997). A Nation at War: Australian Politics, Society and Diplomacy During the Vietnam War 1965–1975. The Official History of Australia's Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1975. Vol. Six. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-282-6.

- Edwards, Peter (2014). Australia and the Vietnam War: The Essential History. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing. ISBN 9781742232744.

- Ekins, Ashley; McNeill, Ian (2012). Fighting to the Finish: The Australian Army and the Vietnam War 1968–1975. The Official History of Australia's Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1975. Vol. Nine. St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781865088242.

- Freudenberg, Graham (2009). A Certain Grandeur: Gough Whitlam's Life in Politics (revised ed.). Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-07375-7.

- Frost, Frank (1987). Australia's War in Vietnam. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 004355024X.

- Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69791-0.

- Hackworth, David; Sherman, Julie (1989). About Face, the Odyssey of an American Warrior. Melbourne: MacMillan. ISBN 0-671-52692-8.

- Ham, Paul (2007). Vietnam: The Australian War. Sydney: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-7322-8237-0.

- Harper, James (1990). War Without End. Longman Cheshire. ISBN 0-582-86826-2.

- Hartley, John (2002). "The Australian Army Training Team Vietnam". In Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey (eds.). The 2002 Chief of Army's Military History Conference: The Australian Army and the Vietnam War 1962–1972. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Army History Unit. pp. 240–247. ISBN 0-642-50267-6. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015.

- Horner, David, ed. (1990). Duty First: The Royal Australian Regiment in War and Peace (First ed.). North Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-442227-X.

- Horner, David; ed (2008). Duty First: A History of the Royal Australian Regiment (Second ed.). Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-374-5.

- Jupp, James (2001). The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, its People, and Their Origins. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80789-1.

- Kuring, Ian (2004). Redcoats to Cams: A History of Australian Infantry 1788–2001. Loftus, New South Wales: Australian Military Historical Publications. ISBN 1876439998.

- Lyles, Kevin (2004). Vietnam ANZACs – Australian & New Zealand Troops in Vietnam 1962–72. Elite Series 103. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-702-6.

- McAulay, Lex (1988). The Battle of Coral: Vietnam Fire Support Bases Coral and Balmoral, May 1968. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 0-09-169091-9.

- McKay, Gary; Graeme Nicholas (2001). Jungle Tracks: Australian Armour in Vietnam. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-449-2.

- McNeill, Ian (1984). The Team. Australian Army Advisors in Vietnam 1962–1972. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 0-642-87702-5.

- McNeill, Ian; Ekins, Ashley (2003). On the Offensive: The Australian Army and the Vietnam War 1967–1968. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86373-304-3.

- Nalty, Bernard C. (1998). The Vietnam War. Salamander Books. ISBN 0-7607-1697-8.

- Odgers, George (1988). Army Australia: An Illustrated History. Frenchs Forest: Child & Associates. ISBN 0-86777-061-9.

- O'Keefe, Brendan (1994). Medicine at War: Medical Aspects of Australia's Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1950–1972. The Official History of Australia's Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1975. Vol. Three. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-863733-01-9.

- Palazzo, Albert (2006). Australian Military Operations in Vietnam. Canberra: Army History Unit, Australian War Memorial. ISBN 1-876439-10-6.

- Stephens, Alan (2006). The Royal Australian Air Force: A History (Paperback ed.). South Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-555541-7.

- Stone, Gerald (1966). War Without Honour. Brisbane: Jacaranda Press. OCLC 3491668.

- Woodruff, Mark (1999). Unheralded Victory: Who Won the Vietnam War?. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 0004725409.

- Ross, Andrew; Hall, Robert; Griffin, Amy (2015). The Search for Tactical Success in Vietnam: An Analysis of Australian Task Force Combat Operations. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10709-844-2.

External links

- Vietnam War Bibliography: Australia and New Zealand

- "Australia's Vietnam War: Exploring the Combat Actions of the 1st Australian Task Force". Australian Defence Force Academy.

- "Australia and the Vietnam War". Department of Veterans' Affairs. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.