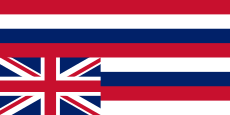

| Part of a series on the |

| Hawaiian sovereignty movement |

|---|

|

| Main issues |

| Governments |

| Historical conflicts |

| Modern events |

| Parties and organizations |

| Documents and ideas |

| Books |

Opposition to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom took several forms. Following the overthrow of the monarchy on January 17, 1893, Hawaii's provisional government—under the leadership of Sanford B. Dole—attempted to annex the land to the United States under Republican Benjamin Harrison's administration. But the treaty of annexation came up for approval under the administration of Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, anti-expansionist, and friend of the deposed Queen Liliuokalani of Hawaii. Cleveland retracted the treaty on March 4, 1893, and launched an investigation headed by James Henderson Blount; its report is known as the Blount Report.

Background

The overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom was a result of progressive governmental control by foreigners and their descendants who were coming in increasing numbers to the islands of Hawaii. Many of these foreigners bought Hawaiian land and invested in the lucrative Hawaiian sugar industry. In 1887, these men forced the then reigning king, Kalākaua, to sign the so-called Bayonet Constitution, which stripped him of much of his power, in turn creating a constitutional monarchy. In 1890, the United States enacted the McKinley Tariff; the new law sharply raised the country's import tariffs, ending the Hawaiian sugar industry's dominance in the North American market and depressing prices, pushing Hawaii into turmoil.[2][3]

Following the sugar crash, in 1893 the reigning Queen Lili'uokalani proposed a new constitution to replace the 1887 one. If adopted, the new constitution would revoke many of the foreigners' powers, and put the queen back in control of the Kingdom. The proposal was backed by the majority of the native population; however, it was naturally opposed by the Americans and other foreigners. Hoping for American intervention, they began planning a coup. Anti-monarchists coalesced, forming the Committee of Safety while royalist leaders formed the Committee of Law and Order in support of the queen and the government.[4] The situation soon escalated as both sides armed themselves. Fearing for American safety, the United States called on USS Boston to land a small force of Marines to protect American interests. Although the Americans were sworn to neutrality and never fired a shot, they did intimidate the royalist defenders, and Queen Lili'uokalani, fearing bloodshed, conceded.[3][5][6]

Blount Report

In an attempt to undo the work of the Harrison administration, Cleveland removed John L. Stevens as Minister to Hawaii, as well as Gilbert C. Wiltse as captain of USS Boston. He then retracted the treaty of annexation from the U.S. Senate, citing the opposition of Hawaiian citizens to annexation. The provisional government then became the Republic of Hawaii.[7]

After withdrawing the annexation treaty, Cleveland sent an emissary (Blount) to investigate the circumstances surrounding the revolution and the situation in Hawaii. The report stated that the provisional government was not established with the consent or approval of the Hawaiian people. It also claimed that Liliuokalani only surrendered after being convinced that the provisional government was supported by the United States and fearing a bloody military conflict. According to Blount, she was told by the revolutionaries that the U.S. president would consider her case after surrendering. After reviewing the report, Cleveland decided not to send back the treaty he had withdrawn. Blount's findings were disputed by the provisional government.[8]

Black Week

On December 14, 1893, Albert Willis arrived in Honolulu aboard USRC Corwin unannounced, bringing an anticipation of an American invasion to restore the monarchy, which became known as the Black Week. Willis was the successor to James Blount as United States Minister to Hawaii. With the hysteria of a military assault, he staged a mock invasion with USS Adams and USS Philadelphia, directing their guns toward the capital. He also ordered Rear Admiral John Irwin to organize a landing operation using troops on the two American ships, which was joined by the Japanese Naniwa and the British HMS Champion.[9][10] After the arrival of Corwin, the provisional government and citizens of Hawaii were ready to rush to arms if necessary, but it was widely believed that Willis' threat of force was a bluff.[11][12]

On December 16, 1893, the British Minister to Hawaii was given permission to land marines from HMS Champion for the protection of British interests; the ship's captain predicted that Liliuokalani would be restored by the U.S. military.[11][12] In a November 1893 meeting with Willis, Liliuokalani indicated that she wanted the revolutionaries punished and their property confiscated, despite Willis' desire for her to grant amnesty to her enemies.[13]

On December 19, 1893, while meeting with the leaders of the provisional government, Willis presented a letter written by Liliuokalani, in which she agreed to grant amnesty to the revolutionaries if she was restored as queen. During the conference, Willis told the provisional government to surrender to Liliuokalani and allow Hawaii to return to its previous condition, but Dole refused to comply with his demands, claiming that he was not subject to the authority of the United States.[8][12][14]

A few weeks later, on January 10, 1894, U.S. Secretary of State Walter Q. Gresham announced that the settlement of the situation in Hawaii would be left up to Congress, citing Willis' unsatisfactory progress. Cleveland said that Willis had carried out the letter of his directions, rather than their spirit.[11]

On January 11, 1894, Willis confirmed that the invasion had been a hoax.[9]

Native Hawaiian Opposition

Response from the queen

Liliuokalani's statement yielding authority, on January 17, 1893, protested the overthrow:[15]

I Liliuokalani, by the Grace of God and under the Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the Constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a Provisional Government of and for this Kingdom.

That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America whose Minister Plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the Provisional Government.

Now to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do this under protest and impelled by said force yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the Constitutional Sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.

Dole received her letter, but neither read it nor challenged her claim of surrendering to the "superior force of the United States of America."[15] He then sent representatives to Washington, D.C. to negotiate a treaty of annexation.[7]

Efforts by native Hawaiians

Natives of the Hawaiian Islands rallied behind two groups: Hui Aloha ʻĀina (Hawaiian Patriotic League) and Hui Kālaiʻāina (Hawaiian Political Association). The majority of native Hawaiians refused to sign an oath of loyalty to the provisional government, and continually protested against the proposed constitution of 1894 - the women’s branch of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina wrote to western foreign ministers, calling the constitution “illiberal and despotic”.[16]

The Royal Hawaiian Band refused to take the oath of loyalty, and were promptly fired, and, without a wage, were told that they would ‘soon be eating rocks’. The band reformed separately from the government and performed in the United States to raise awareness for the Hawaiian cause. The ‘Rock-eating song’ composed at the time is still sung today.[17]

On January 5, 1895, native islanders staged an armed revolution - the 1895 Wilcox rebellion - but the attempt was quelled by Republic of Hawaii supporters. Those leading the attempt were jailed, along with Liliuokalani, who was accused of not stopping the revolt.[18][19] Native Hawaiian women made and wore striped dresses in solidarity with those imprisoned, and the women’s branch of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina cared for the families of those who were jailed.[20]

Resistance to annexation

Protest against annexation by Liliuokalani

June 17, 1898 official protest from Queen Liliuokalani in Washington, DC.[21]

I, Liliuokalani of Hawaii, by the will of God named heir apparent on the tenth day of April, A.D. 1877, and by the grace of God Queen of the Hawaiian Islands on the seventeenth day of January, A.D. 1893, do hereby protest against the ratification of a certain treaty, which, so I am informed, has been signed at Washington by Messrs. Hatch, Thurston, and Kinney, purporting to cede those Islands to the territory and dominion of the United States. I declare such a treaty to be an act of wrong toward the native and part-native people of Hawaii, an invasion of the rights of the ruling chiefs, in violation of international rights both toward my people and toward friendly nations with whom they have made treaties, the perpetuation of the fraud whereby the constitutional government was overthrown, and, finally, an act of gross injustice to me.

Because the official protests made by me on the seventeenth day of January, 1893, to the so-called Provisional Government was signed by me, and received by said government with the assurance that the case was referred to the United States of America for arbitration.

Because that protest and my communications to the United States Government immediately thereafter expressly declare that I yielded my authority to the forces of the United States in order to avoid bloodshed, and because I recognized the futility of a conflict with so formidable a power.

Because the President of the United States, the Secretary of State, and an envoy commissioned by them reported in official documents that my government was unlawfully coerced by the forces, diplomatic and naval, of the United States; that I was at the date of their investigations the constitutional ruler of my people.

Because neither the above-named commission nor the government which sends it has ever received any such authority from the registered voters of Hawaii, but derives its assumed powers from the so-called committee of public safety, organized on or about the seventeenth day of January, 1893, said committee being composed largely of persons claiming American citizenship, and not one single Hawaiian was a member thereof, or in any way participated in the demonstration leading to its existence.

Because my people, about forty thousand in number, have in no way been consulted by those, three thousand in number, who claim the right to destroy the independence of Hawaii. My people constitute four-fifths of the legally qualified voters of Hawaii, and excluding those imported for the demands of labor, about the same proportion of the inhabitants.

Because said treaty ignores, not only the civic rights of my people, but, further and longer across the land, the hereditary property of their chiefs. Of the 4,000,000 acres composing the territory said treaty offers to annex, 1,000,000 or 915,000 acres has in no way been heretofore recognized as other than the private property of the constitutional monarch, subject to a control in now way differing from other items of a private estate.

Because it is proposed by said treaty to confiscate said property, technically called the crown lands, those legally entitled thereto, either now or in succession, receiving no consideration whatever for estates, their title to which has been always undisputed, and which is legitimately in my name at this date.

Because said treaty ignores, not only all professions of perpetual amity and good faith made by the United States in former treaties with the sovereigns representing the Hawaiian people, but all treaties made by those sovereigns with other and friendly powers, and it is thereby in violation of international law.

Because, by treating with the parties claiming at this time the right to cede said territory of Hawaii, the Government of the United States receives such territory from the hands of those whom its own magistrates (legally elected by the people of the United States, and in office in 1893) pronounced fraudulently in power and unconstitutionally ruling Hawaii.

Therefore I, Liliuokalani of Hawaii, do hereby call upon the President of that nation, to whom alone I yielded my property and my authority, to withdraw said treaty (ceding said Islands) from further consideration. I ask the honorable Senate of the United States to decline to ratify said treaty, and I implore the people of this great and good nation, from whom my ancestors learned the Christian religion, to sustain their representatives in such acts of justice and equity as may be in accord with the principles of their fathers, and to the Almighty Ruler of the universe, to him who judgeth righteously, I commit my cause.

Done at Washington, District of Columbia, United States of America, this seventeenth day of June, in the year eighteen hundred and ninety-seven.

[Endorsement]

Efforts against annexation by native Hawaiians

After William McKinley, who favored annexation, became President of the United States in 1897, a new treaty of annexation was signed and sent to United States Senate for approval. In response, the Hawaiian Patriotic League and its female counterpart petitioned Congress, opposing the annexation treaty. In September and October of that year, Hui Aloha ʻĀina collected 556 pages for a total of 21,269 signatures of native Hawaiians — or over half of native residents — opposing annexation. Hui Kālaiʻāina collected around 17,000 signatures for restoring the monarchy, but their version has been lost to history.

Four Hawaiian delegates: James Keauiluna Kaulia, David Kalauokalani, William Auld, and John Richardson traveled to Washington, DC to present the Kūʻē Petitions to Congress which convened in December. After presenting the petition to the U.S. Senate and then lobbying senators, they were able to force the treaty's failure in 1898.[18][19]

However, in 1898, the Senate passed the Newlands Resolution due to the Spanish–American War; the resolution resulted in Hawaii's annexation for use as a Pacific military base.[18]

References

- ^ Spencer, Thomas P. (1895). Kaua Kuloko 1895. Honolulu: Papapai Mahu Press Publishing Company. OCLC 19662315.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 533, 587–588.

- ^ a b "Teaching With Documents: The 1897 Petition Against the Annexation of Hawaii". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 593; Menton & Tamura 1999, pp. 21–23

- ^ Russ 1992, p. 67: She...defended her act[ions] by showing that, out of a possible 9,500 native voters in 1892, 6,500 asked for a new Constitution.

- ^ "On This Day: A Revolution In Hawaii". The New York Times. January 28, 1893. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ a b Carter 1897, p. 101

- ^ a b "Defied By Dole". Clinton Morning Age. Vol. 11, no. 66. January 10, 1894. p. 1.

- ^ a b Report Committee Foreign Relations, United States Senate, Accompanying Testimony, Executive Documents transmitted Congress January 1, 1893, March 10, 1891, p 2144

- ^ History of later years of the Hawaiian Monarchy and the revolution of 1893 By William De Witt Alexander, p 103

- ^ a b c "Hawaiian Papers". Manufacturers and Farmers Journal. Vol. 75, no. 4. January 11, 1894. p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Willis Has Acted". The Morning Herald. United Press. January 12, 1894.

- ^ "Minister Willis's Mission" (PDF). The New York Times. January 14, 1894.

- ^ "Quiet at Honolulu". Manufacturers and Farmers Journal. Vol. 75, no. 4. January 11, 1894. p. 2.

- ^ a b Kuykendall 1967, p. 603

- ^ Silva, Noenoe K. (2006). Aloha betrayed: native Hawaiian resistance to American colonialism. A John Hope Franklin Center Book (4. print ed.). Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0-8223-3350-0.

- ^ Silva, Noenoe K. (2006). Aloha betrayed: native Hawaiian resistance to American colonialism. A John Hope Franklin Center Book (4. print ed.). Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-8223-3350-0.

- ^ a b c Schamel, Wynell and Charles E. Schamel. "The 1897 Petition Against the Annexation of Hawaii." Social Education 63, 7 (November/December 1999): 402–408.

- ^ a b Noenoe K. Silva (1998). "The 1897 Petitions Protesting Annexation". Archived from the original on 2012-03-17. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ^ Silva, Noenoe K. (2006). Aloha betrayed: native Hawaiian resistance to American colonialism. A John Hope Franklin Center Book (4. print ed.). Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8223-3350-0.

- ^ "Lili'uokalani's Protest to the Treaty of Annexation". www.hawaii-nation.org.

Bibliography

- Carter, W. S., ed. (August 1897). "The Annexation of Hawaii". Locomotive Firemen's Magazine. 23 (2).

- Kuykendall, Ralph S. (1967). The Hawaiian Kingdom, Volume 3: 1874–1893, The Kalakaua Dynasty. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1.

- Menton, Linda K.; Tamura, Eileen (1999). A History of Hawaii, Student Book. Honolulu: Curriculum Research & Development Group. ISBN 978-0-937049-94-5. OCLC 49753910.

- Russ, William Adam (1992). The Hawaiian Revolution (1893–94). Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-0-945636-43-4.

Further reading

- Dewey, Davis Rich (1907). National problems, 1885–1897. Harper & Brothers.

- Van Dyke, Jon M. (2007). Who Owns the Crown Lands of Hawaii?. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3210-0.