| Probrachylophosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

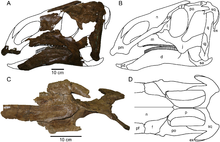

| Skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Saurolophinae |

| Genus: | †Probrachylophosaurus Freedman Fowler & Horner, 2015 |

| Species: | †P. bergei

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Probrachylophosaurus bergei Freedman Fowler & Horner, 2015

| |

Probrachylophosaurus bergei is a species of large herbivorous brachylophosaurin hadrosaurid dinosaur known from the Late Cretaceous Campanian Judith River Formation, of Montana and the Foremost Formation of Alberta.[1]

The significance of this particular hadrosaur taxon is that it is a transitional species between the genera Acristavus and Brachylophosaurus evolving from a crestless ancestor (the former genus) to its crested descendant (the latter genus) while changing the morphology of its nasal bones.[2]

Discovery and naming

In 1981 and 1994, Mark Goodwin of the University of California Museum of Paleontology excavated limb bones and a vertebra near Rudyard in the north of Montana, at a site originally discovered by Kyoko Kishi. After a school class found some more bones, in 2007 and 2008 a team of the Museum of the Rockies secured the remainder of a hadrosaur skeleton, among which the skull. The fossil was donated to the Museum of the Rockies by land owners Nolan and Cheryl Fladstol; and John and Claire Wendland.[2] In 2009, 2010 and 2011, the find was reported in the scientific literature as a possible new species of Brachylophosaurus.[3][4][5]

In 2015, the type species Probrachylophosaurus bergei was named and described by Elizabeth A. Freedman Fowler and Jack Horner. The generic name is a combination of Latin pro, "before", and Brachylophosaurus and refers to the genus being situated in a lower position in the stratification than its relative Brachylophosaurus. The specific name honours Sam Berge, one of the landowners, and his friends who have supported the research.[2] Probrachylophosaurus was one of eighteen dinosaur taxa from 2015 to be described in open access or free-to-read journals.[6]

The holotype, MOR 2919, was found in a layer of the Judith River Formation dating from the Campanian and being between 79.8 and 79.5 million years old, plus or minus two hundred thousand years. It consists of a partial skeleton with skull, of an adult individual. It contains the right premaxilla, both maxillae, the left jugal, a part of the right lacrimal, the rear of a left nasal bone, the middle part of a right nasal bone, the skull roof from the frontal bones to the exoccipitals, both squamosals, both quadrate bones, the predentary of the lower jaws, both dentaries, a right surangular, eleven neck vertebrae, eleven back vertebrae, twenty-nine tail vertebrae, nineteen chevron bones, nineteen ribs, the entire pelvis, both lower legs, a right second metatarsal and a right fourth metatarsal. The bones have not been found in articulation.[2]

Specimen MOR 1097, a fragmentary skull of a subadult individual, was referred to the species. It had been found at a kilometre distance from the holotype.[2]

Description

Probrachylophosaurus is a large hadrosaurid. Its holotype is the largest brachysaurolophin specimen known.[2] Because of this size the fossil has been nicknamed "Super-Duck". Its size has been estimated at 10 metres (33 ft) in length and 5 metric tons (5.5 short tons) in body mass.[7] Recent body mass estimate suggests that it reached more than 4.3 metric tons (4.7 short tons).[8]

In 2015, several distinguishing traits were established. Two of these are autapomorphies, unique derived characters. The skull crest is made of massive bone and is entirely formed by the nasal bones which, in adult individuals, overhang the supratemporal fenestrae over a distance of less than two centimetres. This crest is at its midline extremely thickened, resulting at the position of the rear frontals bones it overgrowths, in a pointed strongly triangular transverse cross-section, the upper angle of which in rear view is less than 130°. Additionally, these autapomorphies form a unique combination with traits that in themselves are not unique. The rear lacrimal bone is transversely wide as in Acristavus but not Brachylophosaurus. Of the front branch of the jugal, the lower corner is positioned behind the level of the upper corner, as with Acristavus but not Brachylophosaurus. The squamosals touch each other at the skull midline as with Acristavus but not Brachylophosaurus. The nasal bone skull crest is massive and almost horizontally oriented to the rear as in Brachylophosaurus but different from Acristavus.[2]

Classification

Probrachylophosaurus was, within the Hadrosaurinae, placed in the Brachylophosaurini by the describing authors. Adding the traits of Probrachylophosaurus to two earlier datasets of cladistic analyses, resulted in slightly conflicting positions. In one analysis it was recovered as the sister species of Brachylophosaurus; in the other as a sister species of a clade consisting of Brachylophosaurus and Maiasaura. In both evolutionary trees Acristavus was in a more basal position. The authors suggested that Acristavus might have been a direct ancestor of Probrachylophosaurus and the latter, in view of its intermediate smaller crest form, again an ancestor of Brachylophosaurus that lived about 1.5 million years later.[2]

The revised analysis of Albert Prieto-Márquez resulted in the following evolutionary tree:[2]

Paleobiology

The describing article also published the result of histological research of the bone structure of the left shinbone of the type specimen. This bone showed fourteen LAGs, lines of arrested growth, that likely represented yearly seasons of low food intake. The age of the holotype would thus be about fourteen years. The distance between the lines indicated this individual had not yet reached its maximum size, but closely approached it, proof that it was not simply a subadult Brachylophosaurus specimen with a small crest.[2]

The lines also showed a general slowing of the growth after the fifth year. This could have been an indication sexual maturity was reached at that age. If so, the onset of maturity was about two years later than with Maiasaura.[2]

References

- ^ Thompson, Michael G.W.; Bedek, Fern V.; Schröder-Adams, Claudia; Evans, David C.; Ryan, Michael J. (2021-10-01). "The oldest occurrence of brachylophosaurin hadrosaurids in Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 58 (10): 993–1004. Bibcode:2021CaJES..58..993T. doi:10.1139/cjes-2020-0007. ISSN 0008-4077. S2CID 238720084.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fowler, Elizabeth A. Freedman, and John R. Horner. "A New Brachylophosaurin Hadrosaur (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) with an Intermediate Nasal Crest from the Campanian Judith River Formation of Northcentral Montana." PLOS One 10.11 (2015): e0141304.

- ^ Freedman, E.A., 2009, "Variation in nasal crest size of Brachylophosaurus canadensis (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae): Ontogenetic and stratigraphic implications of a large new specimen from the Judith River Formation of northcentral Montana", Abstracts of papers, Sixty-ninth Annual Meeting, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (3): 99A-100A

- ^ Freedman, E.A., and Fowler, D.W., 2010, "Stratigraphic correlation of Judith River Formation (Campanian, Upper Cretaceous) exposures in Kennedy Coulee (northcentral Montana) to the Foremost Formation (Alberta): implications for anagenesis in hadrosaurid dinosaurs", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, SVP Program and Abstracts Book, 92

- ^ Freedman, E.A., 2011, "A new species of Brachylophosaurus (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae) from the Judith River Formation (Late Cretaceous: Campanian) of northcentral Montana", International Hadrosaur Symposium, Royal Tyrrell Museum, Drumheller, Alberta. Abstract Volume, 53-54

- ^ "The Open Access Dinosaurs of 2015". PLOS Paleo. Archived from the original on 2017-07-15. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-1-78684-190-2. OCLC 985402380.

- ^ Wosik, M.; Chiba, K.; Therrien, F.; Evans, D.C. (2020). "Testing Size–frequency Distributions As a Method of Ontogenetic Aging: A Life-history Assessment of Hadrosaurid Dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada, with Implications for Hadrosaurid Paleoecology". Paleobiology. 46 (3): 379–404. Bibcode:2020Pbio...46..379W. doi:10.1017/pab.2020.2.