| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | President Hoover |

| Namesake | Herbert Hoover |

| Owner | Dollar Steamship Lines[1] |

| Operator | Dollar Steamship Lines |

| Port of registry | San Francisco[1] |

| Route | |

| Ordered | 26 October 1929[4] |

| Builder | Newport News Shipbuilding[1] |

| Yard number | 339[5] |

| Laid down | 25 March 1930[6] |

| Launched | 9 December 1930[4][7] |

| Completed | 11 July 1931 (delivered)[6] |

| Out of service | 12 December 1937[8] |

| Homeport | San Francisco |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Ran aground, 11 December 1937; written off and scrapped in situ[3][7][8] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | |

| Beam | 81.0 ft (24.7 m)[1] |

| Draft | 34 ft (10 m)[7] |

| Depth | 52.0 ft (15.8 m)[1] |

| Installed power | 26,500 shp[4] |

| Propulsion | |

| Speed | 20.5 knots (38 km/h; 24 mph) cruising;[5] 22.2 knots (41 km/h; 26 mph) maximum[7] |

| Capacity | |

| Crew | 324 (1930);[7][10] 330 (1937)[2] |

| Sensors and processing systems | direction finding equipment[1] |

| Notes | sister ship: President Coolidge |

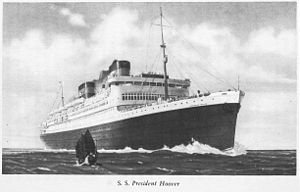

SS President Hoover was an ocean liner built for the Dollar Steamship Lines. She was completed in 1930 and provided a trans-Pacific service between the US and the Far East. In 1937 she ran aground on an island off Formosa (now known as Taiwan) during a typhoon and was declared a total loss. She had a sister ship, President Coolidge, that was completed in 1931, was made a troopship in 1941 and was lost after striking a mine while attempting to enter the harbor at Espiritu Santo in 1942.

History

Building

Dollar Lines ordered both the President Hoover and President Coolidge on 26 October 1929.[4] The Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company of Newport News, Virginia, USA, built the two ships, completing the Hoover in 1930 and Coolidge in 1931.[1] They were the largest merchant ships built in the USA up to that time.[7] First Lady Lou Henry Hoover launched and christened President Hoover on December 9, 1930.[4][7]

Each ship had turbo-electric transmission, with a pair of steam turbo generators generating current that powered propulsion motors on the twin propeller shafts. Westinghouse built the turbo generators and propulsion motors for President Coolidge but General Electric built the turbo generators and propulsion motors for President Hoover.[1] 12 oil-fired Babcock & Wilcox high-pressure boilers supplied the steam for President Hoover's turbo-generators.[4] The electric propulsion motors produced 26,500 shp at 133 RPM.[4]

President Hoover's accommodation was air conditioned[4] and there was a 'phone in every cabin.[10] There were swimming pools on deck,[10] gymnasiums,[10] a dance floor[8] and Otis elevators.[4] Décor was in contemporary Art Deco style and the First Class lounge was decorated with murals by the artist Frank Bergman of New York.[4]

Robert Dollar had bought his first ship in 1895, founded Dollar Lines in 1903 and was now 87 years old. On August 6, 1931, three days before President Hoover was launched, he toured her and declared "This ship is a wonder".[4][10] Dollar lived until May 1932, just a few months after President Hoover and President Coolidge made their maiden voyages.

Trans-Pacific service

President Hoover and President Coolidge ran between San Francisco and Manila via Japan and China.[7] The United States Postal Service subsidised them to carry mail, which helped Dollar to run the two ships at a profit.[7]

However, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931–32, the Japanese attack on the Great Wall in 1933 and the Japanese invasion of China starting in July 1937 all deterred US travel to the Far East, and Dollar Lines became increasingly unprofitable.[7]

Bombed in the Yangtze River

After the Battle of Shanghai had broken out in August 1937, President Hoover was diverted from Hong Kong to evacuate US nationals from Shanghai.[3] On 30 August[11][12] the liner was moored in the Yangtze River, awaiting clearance to enter the Wusong River[3] to reach the Port of Shanghai when, despite a 30-foot (9.1 m)-long[2] US flag draped on her top deck abaft the bridge[3] to identify her to aircraft as a neutral US ship, the Republic of China Air Force mistook her for the Japanese troopship Asama Maru and bombed her.[3][13]

One bomb hit President Hoover's top deck, killing a crewman from the mess hall.[3] Fragments from another bomb penetrated the main saloon, wounding six crew and two passengers.[3] One of President Hoover's radio officers transmitted a distress call stating that Chinese aircraft were attacking her.[3] Both an IJN destroyer and a Royal Navy cruiser came in response, but in the event only medical help was needed.[3] Despite her casualties President Hoover sustained only minor damage, but she aborted the rescue mission to Shanghai[3] and returned to San Francisco for repairs.[2]

Chiang Kai-shek, leader of China's National Military Commission, had known Robert Dollar and was reportedly furious that his aircraft had attacked his late friend's ship.[2] He threatened to have the officer responsible executed until he found that it was his chief air force advisor Claire Lee Chennault.[2] Chiang's wife Soong Mei-ling had hired Chennault only two months previously, and the Generalissimo relented and instead paid the Texan a $10,000 bonus soon afterwards.[2]

Aground on Kasho-to

After repairs President Hoover returned to service, departing from San Francisco on 22 November 1937[3] for Kobe and Manila.[2] She was barely more than half-full, with only 503 passengers.[2] During the voyage the Dollar Lines management signaled President Hoover's Master, George W Yardley, "You must be in Manila, absolutely urgent that you arrive not later than 6 a.m. 12th December,[3] make all possible speed".[8]

President Hoover's course from Kobe to Manila avoided Hong Kong, Shanghai and the Taiwan Strait in order to keep clear of the Sino-Japanese War zone.[2][3] Instead President Hoover took an unfamiliar course down the east coast of Taiwan,[3][8] which since 1895 had been under Japanese rule. The Japanese colonial authorities had turned off the lighthouses in Taiwan so Hoover navigated by dead reckoning.[3] A strong monsoon blowing from the northeast made it difficult to calculate her course accurately,[8] and a heavy mist made visibility extremely poor.[3]

At about 0100 hrs on 11 December[2][3] (local date) President Hoover struck a reef about 500 metres (1,600 ft)[2][3] from the shore of Zhongliao Bay[2] on the north coast of Kasho-to (綠島),[8] a volcanic island about 18 nautical miles (33 km) off Taitung City in south-eastern Taiwan. Her bottom was torn open as far aft as her engine room[8] and she came to rest with a slight list to port.[3] At about 0200 hrs[3] President Hoover fired distress flares and her radio officer sent an SOS signal.[2] The Hamburg America Line cargo ship D/S Preußen received the SOS and arrived around dawn, but the heavy sea[2] and shallow water[3] prevented her from approaching close enough to help.

Captain Yardley tried at first to refloat the ship by having the crew jettison cargo and bunker oil overboard.[2][3] Thick black fuel oil spread over the sea and onto the beach,[8] either deliberately discharged[2] or through the reef damaging the ship's bunkers. But as the monsoon continued to blow from the northeast, and lightening President Hoover only helped the wind and strong waves to drive her further onto the reef until she was only 100 metres (330 ft) from shore.[2][3]

A junior member of the Purser's department, Eugene Lukes, recalled:

... the general alarms went off, and we were getting all the passengers out, getting everybody up on deck. It was blowing, the seas were starting to smack against the side of the ship, it was pitch black. And pretty soon we could see little bobbing lights along the shoreline, little oil lanterns so we obviously stirred up the natives. As it got lighter we could see that we had ripped out the bottom almost clear back to the engine room. There was a lot of oil, and it oiled the sea and the beach. There was no backing off, so we had to get the passengers ashore. We lowered the lifeboats with people in them.[8]

Some of the villagers of Zhongliao fled to the mountains because at the sight of President Hoover close to shore, and the sound and sight of her distress flares, they feared that the Sino-Japanese fighting had reached their island.[2][3] With the dawn, villagers realised what had really happened, and put to sea in motor fishing boats to help.[3][8]

Abandoning the ship

President Hoover's crew prepared to evacuate passengers.[8] In order to keep boats on course between the ship and the shore in the monsoon wind, they put a wire cable ashore and tautened it with a winch aboard ship.[8] In each boat two crewmen wearing strong gloves, one each in the bow and the stern, would slide their hands along the cable to guide boats from ship to shore.[8] Some passengers alleged that President Hoover's crew were inexperienced, and that when trying to get the wire cable ashore to prepare for the evacuation they capsized two of the lifeboats in shallow water.[14]

At low tide around 1300 hrs Yardley ordered the evacuation of the passengers.[2][3] President Hoover's crew lowered her lifeboats, villagers approached with their boats and both ferried passengers ashore.[8] It took about 15 minutes for a boat to make each trip along the cable from ship to shore.[3] Because of the black oil on the water, some of the women passengers were reluctant to step from the lifeboats to wade ashore, so crewmen carried them.[8] At about 1500 hrs the flagship of the Japanese 4th Fleet, the Myōkō-class cruiser Ashigara arrived with an unidentified Mutsuki-class destroyer to observe and protect President Hoover.[2] It took 36 hours from the line being secured to the last passenger being brought ashore.[2][3]

There were no deaths, but some passengers suffered hypothermia in the December wind and cold and were treated by the ship's doctor.[3] From where they landed the survivors had to walk about 2 miles (3 km) to Zhongliao village.[3] There as many as possible were accommodated in the village school, with the remainder being distributed to villagers' houses.[3]

According to Time, while the passengers were being taken ashore a small number[3] of the crewmen aboard President Hoover plundered the ship's liquor supply.[2]

According to Dr. Claude Conrad, a missionary official of Washington, D. C.: "A majority of the ship's crew came into camp more or less incapacitated and abusive from the effects of free indulgence in the ship's liquor stores. Out of control of officers partially in the same condition, many of the crew men continued most of the night terrorizing passengers and natives." However, when the liquored seamen began hunting for women passengers sleeping in scattered houses ashore, some officers and other passengers formed a vigilante group to protect them. There was no actual molestation. There would have been no disturbance at all ashore, said some of the passengers, if the Hoover's officers had been permitted by Japanese police to land with their guns.[14]

Other witnesses reported that some of the passengers also got drunk.[3]

Repatriation from Kasho-to

The US Navy had sent two Clemson-class destroyers to help: USS Alden from Manila and USS Barker from Olongapo Naval Station.[3] However, in the heavy sea they made only 12 knots (22 km/h) and did not arrive until 1245 hrs the next day, 12 December.[3] A Japanese officer from Ashigara boarded Alden and cleared the two US warships to enter Japanese territorial waters.[3] Alden sent a party of two officers and 15 enlisted men aboard President Hoover to secure her specie vault, whose contents included registered mail and other valuables, and both destroyers sent landing parties ashore to restore order among the survivors.[3]

On 12 December at about 1500 hrs a Japanese cargo ship, Toriyama Maru, arrived to deliver food and other necessities to the survivors.[3] On 13 December American Mail Line's President McKinley arrived offshore.[3][8]

On the morning of 14 December news reached Alden and Barker that two days earlier Japanese aircraft had sunk the US gunboat USS Panay in the Yangtze River near Nanjing.[3] Alden and Barker discreetly prepared racks of ammunition for their 4"/50 caliber guns, but the IJN ships continued to stand by and assist.[3] President McKinley moved closer inshore and embarked about 400 of President Hoover's passengers and about 230 of her crew.[3] Japanese Navy flat-bottomed boats brought them from the shore out to meet President McKinley's boats and a motor launch, which then ferried them out to the liner.[3] President McKinley then left for Manila, leaving behind President Hoover's officers, steerage passengers and the last 100 of her crew on Kasho-to.[3]

On 15 December Dollar Lines' President Pierce arrived and rescued President Hoover's steerage passengers, officers and remainder of her crew.[3][8] USS Alden remained guarding the wreck until 23 December, when the Japanese authorities took over.[3]

Aftermath

Many failed attempts were made to rescue the ship.[7] In February 1938 President McKinley returned, bringing Chinese laborers and Dollar Lines personnel who carried out some salvage and recovery work.[3] Dollar Lines surveyed the ship and concluded that she would be a constructive total loss.[3][7] Dollar Lines stripped what it could from the wreck and then sold her for $500,000 to the Kitagawa Ship Salvage Company,[3][7]

It took the Japanese salvagers the next three years to break up the wreck.[3][7] By then Dollar Steamship Lines as a company had ceased to exist. In June 1938 President Hoover's sister ship President Coolidge was arrested for an unpaid debt of $35,000,[2] and in August 1938 the United States Maritime Commission intervened by reorganising the company as American President Lines.

Members of the US public gave money to the American Red Cross for a lighthouse to be built near Zhongliao village on Kasho-to (now called Green Island).[2] Lyudao Lighthouse was designed by Japanese engineers, built by local islanders in 1938[2] and is 33.3 metres (109 ft) high.[15]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lloyd's Register, Steamships and Motor Ships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1933. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "Part Two: The Wreck of the SS President Hoover". SS President Hoover. The Takao Club. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay Tully, Anthony; Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander (2012). "Stranding of S.S. PRESIDENT HOOVER – December 1937". Rising Storm – The Imperial Japanese Navy and China 1931–1941. Imperial Japanese Navy Page. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Part One: Robert Dollar and the SS President Hoover". SS President Hoover. The Takao Club. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b Vleggert, Nico; Pablobini; Gothro, Phil (10 January 2012). "SS President Hoover (+1937)". WreckSite. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Newport News Shipbuilding & Drydock Company". Pacific Marine Review. Vol. 28, no. 9. September 1931. p. 387. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Hoover Namesakes". Hoover Heads. Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Memoirs of the Sea List". Narrative. American President Lines. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Lloyd's Register, Steamers & Motorships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1934. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Traveling in style". Vessel History. American President Lines. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ United States Department of State (1937). "Foreign Relations of the United States Diplomatic Papers, 1937, The Far East, Volume IV (Cables: The bombing of the American Dollar Line steamship President Hoover by Chinese aviators)". United States Department of State. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ "The inexperience of Chinese airmen ..." The China Journal. XXVII (3). September 1937. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander; Tully, Anthony (2012). "The Beginning of The Second Sino-Japanese War – "The Marco Polo Bridge Incident" and the Fall of Peiping and Shanghai – 1937". Rising Storm – The Imperial Japanese Navy and China 1931–1941. Imperial Japanese Navy Page. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b "The Hoover Affair". Time. 27 December 1937. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "Lyudao Lighthouse". About Taitung. Department of Culture and Tourism, Taitung Government. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

External links

- Photo: Turbo-Electric Passenger Liner President Hoover

- "America's Finest For Transpacific Service" (August 1931 feature article on ship with photos)

- "A New Spirit in the Architectural Treatment of Passenger Accommodations" (August 1931 feature article, pages 317–326, on ship's passenger spaces with photos)

- "Outfitting A Modern American Liner" (series of pieces, pages 327–339, on ship equipment and systems, photos)

- Ship profile & plans