The Farmers' Market Nutrition Program (FMNP) is a federal assistance program in the United States associated with the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (known as WIC) that provides fresh, unprepared, locally grown fruits and vegetables and nutrition education to WIC participants. Women, infants (over four months old) and children that have been certified to receive WIC program benefits or who are on a waiting list for WIC certification are eligible to participate in the FMNP.[1]

The Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program (SFMNP) is a related program that targets low-income seniors, generally defined as individuals who are at least 60 years old and who have household incomes of not more than 185 percent of the federal poverty level.[2] Eligible recipients in both programs receive coupons in addition to their regular benefits which can be used to buy eligible foods from farmers, farmers' markets or roadside fruit and vegetable stands that have been approved by the state agency to accept coupons.[1] As such, both programs have been noted for increasing the accessibility of fresh fruits and vegetables among low-income populations.[3][4][5]

Together, the FMNP and SFMNP inject an estimated $40 million into farmers' markets annually, and have been instrumental in subsidizing the creation and operation of numerous new farmers' markets in underserved communities, especially in New York City.[5][6][7] National FMNP funding, however, has remained stagnant for several years. It is currently at $20 million per year, with no signs that this amount is likely to increase in the near future.[8] A nascent body of academic literature has focused on various aspects of the programs including health and nutrition outcomes; barriers to participation; and farmer benefits.

Context

Low-income consumers often face inadequate food environments ("food deserts") in which the accessibility of healthy foods including fresh fruits and vegetables is severely limited. Few food retail outlets combined with the high cost of healthy food options contribute to poor food selections for many low-income consumers.[9][10] As such, convenience stores, which stock heavily processed, energy-dense foods, along with fast food restaurants are often the main sources of nutrition for residents of many low-income communities.[11]

Low income then is associated with lower than average intakes of both fruits and vegetables. Fewer than one in five WIC children consume the recommended quantity of vegetables each day, while fewer than half consume the recommended quantity of fruits. The elderly also suffer from insufficient fruit and vegetable intake.[12] Negative health outcomes among low-income consumers including rising obesity rates then have increasingly been linked to unequal access to fresh and healthy food.[13] The FMNP and SFMNP represent attempts at increasing the accessibility and consumption of healthy, fresh foods among low-income populations through a comprehensive approach including the distribution of coupons to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables, and nutrition education for program participants.[1][2] The programs are designed to create incentives for participants to seek out fresh produce in venues that highlight its appeal.[12]

History

Farmers' Market Nutrition Program

The WIC Farmers' Market Nutrition Act of 1992 that established the FMNP was introduced to the House of Representatives on November 5, 1991, by Democratic Representative Dale Kildee, and was co-sponsored by Democratic Representative William D. Ford and Republican Representative William F. Goodling. The purpose of the act was to authorize grants for state programs designed to: (1) provide nutritious unprepared foods (such as fruits and vegetables) from farmers' markets to women, infants, and children who are nutritionally at risk; and (2) expand the awareness and use of farmers' markets and increase their sales. The bill passed in the House on June 22, 1992, and in the Senate on June 23, 1992. It was signed by President George H. W. Bush and became Public Law No. 102-314 on July 2, 1992. The act amended the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act and the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 to make the special supplemental food (WIC) farmers' market program permanent and open to all states.[14]

Three nondiscretionary provisions were mandated in the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 regarding the FMNP including the option to authorize roadside stands, a reduction in the required amount of state matching funds, and an increase in the maximum Federal benefit level. These changes were intended to increase state agency flexibility in managing the FMNP Program. The first two provisions became effective on October 1, 2004, while the increased maximum Federal FMNP benefit level was effective as of June 30, 2004.[15] The program was reauthorized through 2015 by Congress in the passage of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, which was signed by President Barack Obama on December 13, 2010 and became Public Law 111-296.[16] Most recently, FMNP is funded at approximately $22.3 million for Fiscal Year 2018.[1]

Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program

In 2001, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) began the Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program (SFMNP) as a pilot program to improve the diets of low-income seniors. The SFMNP has three purposes: (1) to provide fresh, nutritious, fruits and vegetables from farmers' markets, roadside stands and community supported agriculture; (2) to increase the consumption of agricultural commodities; and (3) to aid in the development of new and additional farmers' markets, roadside stands, and community supported agricultural programs.[17]

The Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002, also known as the 2002 Farm Bill, established the use of $5 million for fiscal year 2002, and $15 million for each of fiscal years 2003 through 2007, of the funds available to the Commodity Credit Corporation to carry out and expand the senior farmers' market nutrition program.[18] The Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008, known as the 2008 Farm Bill, provided $20.6 million annually to operate the program through 2012,[2] and made minor amendments to the program including the exclusion of SFMNP benefits in determining income eligibility for other federal assistance programs and the prohibition of the collection of state or local taxes on purchase of food with SFMNP benefits.[19]

Program Implementation

Farmers' Market Nutrition Program

The FMNP is administered through a federal/state partnership in which the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) provides cash grants to state agencies such as state agriculture departments or health departments. Participating state agencies must provide matching funds for the program in an amount that is equal to at least 30 percent of the administrative cost of the program, except Indian Tribal Organizations which may provide a negotiated match contribution that is less than 30 percent but not less than 10 percent.[20] In fiscal year 2010, grants to states ranged from $6,337 to $3,593,015.[20]

State agencies must submit a State Plan describing the manner in which the state agency intends to implement, operate and administer all aspects of the FMNP within its jurisdiction. Each state agency is responsible for authorizing participating individual farmers, farmers’ markets, and roadside stands. Only authorized producers may accept and redeem FMNP coupons.[1] Participating farmers' markets are selected to participate in the programs based in part on hours of market operation, market location, and the amount and proportion of sales involving fresh, unprocessed fruits and vegetables covered by the FMNP to ensure the greatest accessibility to program participants.[20]

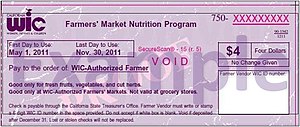

The federal food coupon benefit level for FMNP recipients may not be less than $10 and no more than $30 per year, per recipient. However, state agencies may supplement the federal benefit level.[1] FMNP vouchers are worth $19 on average per person per year.[12] Coupons are submitted to the state agency for reimbursement. Nutrition education is provided by the state agency along with the coupons to improve and expand recipients’ diets by adding fresh fruits and vegetables and to educate them on how to select and prepare the foods purchased with their coupons.[1] Certain foods are not eligible for purchase with FMNP benefits including dried fruits or vegetables, potted fruit or vegetable plants, potted or dried herbs, wild rice, nuts of any kind (even raw), eggs, maple syrup, cider, honey, and molasses.

Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program

The SFMNP is similarly administered through a federal/state partnership. State agencies such as the State Department of Agriculture, Aging, or Health typically administers the program on a state level. The federal SFMNP benefit level, whether a household or individual, may not be less than $20 per year or more than $50 per year. State agencies may also supplement the benefit level with state, local or private funds. SFMNP vouchers are worth $35 on average per person per year.[12]

Eligible foods to be purchased with SFMNP coupons include fresh, nutritious, unprocessed fruits, vegetables, honey, and fresh-cut herbs. State agencies may limit SFMNP sales to specific foods that are locally grown in order to encourage SFMNP recipients to support the farmers in their own states. Certain foods are not eligible for purchase with SFMNP benefits including dried fruits or vegetables, potted fruit or vegetable plants, potted or dried herbs, wild rice, nuts of any kind (even raw), eggs, maple syrup, cider, and molasses. Nutrition education is also provided to SFMNP recipients by the state agency, often through an arrangement with the local WIC agency or through a cooperating senior center.[2]

Controversy

Uneven state implementation has created controversy surrounding the FMNP and the SFMNP as states maintain significant leeway in how they administer the program. While the rules regarding the program are uniform across all states, the scale and methods of implementation are noticeably diverse. The median annual funding level for a state FMNP is around $300,000, and, in general, there is a correlation between state population and FMNP funding. State agencies that applied at the start of each program have had longer to request expansion funds. Large states like California, Texas, and New York boast annual funding of well over $1 million.[8]

However, as the two cases below demonstrate, smaller states in which the farmers market culture is still in its nascent phase have struggled to adequately administer the program to serve all eligible recipients. Unequal funding levels among states combined with significant leeway in state administration of the programs reveal points of contention regarding the implementation and effectiveness of both the FMNP and the SFMNP.

Tennessee

In the summer of 2011, turmoil hit a Memphis farmers' market when an influx of senior citizens flocked to the market to use their SFMNP vouchers. The farmers' market was not equipped to handle the sheer number of customers. Lines, up to three hours long, were prohibitive for the elderly and the few farmers at the market that were certified to accept SFMNP vouchers quickly sold out of their produce. The state of Tennessee's decision to limit voucher use to food grown only by Tennessee farmers; the elimination of an option to use vouchers at roadside stands; miscommunication; and an inefficient and prohibitive farmer certification system were to blame for this volatile situation. The Memphis farmers' market experience with the SFMNP underscores the way in which state implementation of the program can in fact deter recipients from redeeming their coupons and highlights the problems endemic to individual state implementation of the program.[21]

Mississippi

The state of Mississippi has also run into problems with state implementation of the programs. Because of limited state funding for the FMNP, Mississippi is extremely selective in what counties and markets the program is implemented. As a result, recipients can currently use vouchers in only five markets (out of sixty in the whole state) and one farm stand. Limited financial resources have also restricted selection of program participants. If Mississippi offered all WIC participants FMNP vouchers at the current rate, the state could only cover three counties with the program.[8]

Participation

States

Farmers' Market Nutrition Program

In fiscal year 2011, grants were awarded to 46 state agencies and federally recognized Indian Tribal Organizations (ITOs): District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, and 36 states: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

In addition, six ITOs administer the Program: Chickasaw (Oklahoma); Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma; Osage Nation, Oklahoma; the Mississippi Band of Choctaws; the Five Sandoval Indian Pueblos, New Mexico; and the Pueblos of San Felipe, New Mexico.[1]

Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program

In fiscal year 2011, grants were awarded to 51 state agencies and federally recognized Indian Tribal Organizations (ITOs) to operate the SFMNP: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Chickasaw Nation (Oklahoma), Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Five Sandoval Pueblos (New Mexico), Florida, Georgia, Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa & Chippewa Indians (Michigan), Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Oklahoma, Osage Nation (Oklahoma), Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, Rhode Island, San Felipe Pueblo (New Mexico), South Carolina, Standing Rock Sioux (North Dakota), Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.[2]

Expansion

New State agencies are selected based on the availability of funds after base grants for currently participating state agencies are funded.[20] FMNP regulations thus stipulate that maintaining funding at the same level for states already participating in FMNP takes priority in allocation of funds over program expansion either by increasing funding in existing states or by funding new states hoping to participate in the program. These stipulations combined with stagnate overall funding for the FMNP indicate that program expansion into new states is not a priority.[8]

Recipients

In fiscal year 2010, 2.15 million WIC participants received FMNP benefits[1] out of 9.17 million total monthly WIC recipients.[22] In fiscal year 2010, 844,999 low-income seniors received SFMNP benefits.[2]

Farmers

In fiscal year 2010, 18,245 farmers, 3,647 farmers' markets and 2,772 roadside stands were authorized to accept FMNP coupons. Coupons redeemed through the FMNP resulted in over $15.7 million in revenue to farmers for fiscal year 2010.[1] In fiscal year 2010, 106 farmers at 4,601 farmers' markets as well as 3,681 roadside stands and 163 community supported agriculture programs were authorized to accept SFMNP coupons.[2]

Academic Research

Health and Nutrition Benefits

Available research permits no firm conclusions about the impact of the FMNP and SFMNP on participants’ consumption of fresh produce or on any associated nutrition-related effects because of methodological limitations.[20] The extremely low value of the benefits provided in the programs has also been noted to severely limit their ability to drastically improve the diets of program participants.[12] The results of the following studies do, however, provide insights into how the programs may influence fruit and vegetable intake and change behaviors and perceptions related to healthy eating.

- Comparing women from WIC and the FMNP, Kropf et al. (2007), of the School of Human and Consumer Sciences at Ohio University, Athens, found that although household food security status or perceived health status did not differ based on FMNP participation, women who participated in the FMNP had a greater perceived diet quality, greater perceived benefit of fruit and vegetable intake, and were at advanced stages of change with regard to fruit and vegetable intake. Further, vegetable intake servings were greater among FMNP participants.[23]

- Kunkel et al. (2003), of the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition at Clemson University, conducted a survey by mail with a random sample of 1500 SFMNP recipients in South Carolina and found that based on purchasing behavior and self-reports of behavior change, seniors participating in the SFMNP in South Carolina increased their overall fruit and vegetable consumption.[24]

Nutrition Education

The nutrition education component of the FMNP has also been studied by researchers seeking to better understand the effects of the information distributed on program outcomes.

- In an economic evaluation of the FMNP, Just and Weninger (1997), economists from the University of Maryland at College Park, and Utah State University respectively, found that the magnitude of the benefit of the FMNP depends heavily on the benefits of information distributed along with the coupons. Specifically, distributed information improves recipients' abilities to transform fruits and vegetables into better-tasting food or better health; demand is enhanced; and participants benefit directly through increased consumption and indirectly by greater valuation of all fruit and vegetable consumption.[25]

- Anderson et al. (2001) of the Michigan Department of Community Health, the Michigan Public Health Institute, and Michigan State University similarly found through a self-administered survey questionnaire of 455 WIC recipients that combining education about the use, storage, and nutritional value of fruits and vegetables with the use of coupons was critical to the success of the FMNP in Michigan.[26]

Collaboration

Federal/state collaborations define the implementation of both the FMNP and SFMNP. The two research projects below focus on the importance of collaboration in increasing the effectiveness of the FMNP.

- In New York State, three agencies undertook a statewide initiative to increase the effectiveness of the FMNP. In an analysis of this initiative, Conrey et al. (2003), of the Division of Nutritional Sciences at Cornell University, found that enhanced effectiveness of the program as measured by increased redemption rates was possible through a coordinated, collaborative initiative with activities at state and local levels including inter-agency collaboration; hiring a coordinating staff person to focus on the program; supporting capacity building at the local level; and making available high quality resources for program implementation.[27]

- In another study of a collaboration initiative based on the typology of a ‘‘comprehensive, multisectorial collaboration’’ to support the FMNP, Dollahite et al. (2005) also of the Division of Nutritional Sciences at Cornell University, found that collaboration efforts that provided partners with the opportunity to work cooperatively and innovatively improved outcomes for both low-income participants and farmers. Positive outcomes resulted from improved communication and understanding. Community capacity building occurred through the development of strategies to decrease barriers to FMNP participation.[28]

Barriers to Participation

The average FMNP coupon redemption rate between 1994 - 2006 was 59 percent with $28,076,755 issued per year in coupons and $16,616,6855 redeemed.[29] Several important barriers have been identified to participation in the FMNP.

- Caines (2004) in collaboration with The Farmers' Market Alliance and Just Harvest: A Center for Action Against Hunger in Pennsylvania conducted surveys in the waiting rooms of WIC offices in Pennsylvania to ascertain barriers WIC FMNP recipients encounter when redeeming their WIC FMNP checks. Inconvenient market hours were identified as the primary barrier preventing FMNP recipients from shopping at farmers' markets, followed by location and lack of transportation.[30]

Farmer Benefits

United States Department of Agriculture farm subsidies disproportionately benefit commodity crop farmers while farmers who grow fruits and vegetables typically receive no regular direct subsidies.[31] Many small growers then rely on the guaranteed income from the 2008 farm bill’s $15 million Seniors Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program and the separate $25 million Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program.[32] As such, benefits to farmers on the production end of the FMNP and SFMNP have also been the subject of academic research.

- Surveying 102 farmers in South Carolina by mail (53 percent of whom returned the survey) regarding their experiences participating in the SFMNP, Kunkel et al. (2003) discovered that farmers reported positive opinions about the program for both seniors and themselves and expressed a desire for advance notice about the program to prepare for the next year’s crop as many reported running out of fruits and vegetables by the end of the program in September.[24]

- From a survey administered in six states (Iowa, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont, Washington) exploring the economics of the FMNP, Just and Weninger (1997) found that farmers' profits increased by about 8 percent of coupon redemption at the state level, as farmers gain about 7 to 9 percent of the amount of coupon redemption.[25]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "WIC Farmers' Market Nutrition Program". USDA Food and Nutrition Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 12 October 2011. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program". USDA Food and Nutrition Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 12 October 2011. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ Pressler, Margaret (17 August 2003). "Markets, Farmers' Meat and Potatoes". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ Johnson, Pableaux (21 July 2004). "$20 to Spend, Surrounded by Ripeness". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "A More Balanced Farm Bill". The New York Times. 3 April 2002. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012.

- ^ Briggs, Suzanne; Fisher, Andy; Lott, Megan; Miller, Stacy; Tessman, Nell; Community Food Security Coalition; Farmers Market Coalition (June 2010). Real Food, Real Choice: Connecting SNAP Recipients with Farmers Markets (PDF) (Report). Community Food Security Coalition. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Medina, Jennifer (8 October 2004). "Bleak Landscapes, Green Produce; Poor Neighborhoods See Rise in Farmers' Markets". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Broad, Emily; Blake, Myra; Brand, Lee; Greenfield, Matthew; Klein, Jennifer; Knicley, Jared; Kraus, Erica; Policicchio, Jared (May 2010). Food Assistance Programs and Mississippi Farmers Markets (PDF) (Report). Delta Directions. Harvard Law School Mississippi Delta Project. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ Jetter, Karen M; Cassady, Diana L (1 January 2006). "The Availability and Cost of Healthier Food Alternatives". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 30 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.039. PMID 16414422.

- ^ Morland, Kimberly; Wing, Steve; Diez Roux, Ana; Poole, Charles (1 January 2002). "Neighborhood Characteristics Associated with the Location of Food Stores and Food Service Places". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 22 (1): 23–29. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00403-2. hdl:2027.42/56186. PMID 11777675.

- ^ Larson, Nicole I; Story, Mary T; Nelson, Melissa C (1 January 2009). "Neighborhood Environments: Disparities in Access to Healthy Foods in the U.S.". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 36 (1): 74–81. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. PMID 18977112..

- ^ a b c d e "Detailed Information on the Senior and Woman, Infants, and Children Farmers' Market Programs Assessment". Expectmore.gov. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Drewnowski, Adam; Specter, SE (2004). "Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 79 (1): 6–16. doi:10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6. PMID 14684391.

- ^ WIC Farmers' Market Nutrition Act (House resolution 3711). 102nd United States Congress. 11 May 1991. Retrieved 21 October 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Nondiscretionary Provisions of Public Law 108-265, the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004". USDA Food and Nutrition Service. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (Senate Bill 3307). 11th United States Congress. 5 May 2010. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2011. Archived 7 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "USDA Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program". National Resource Center on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Aging. Florida International University. 3 November 2004. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Farm Security and Rural Investment Act (House Resolution 2646). 107th United States Congress. 26 July 2001.

- ^ Food, Conservation, and Energy Act (House Resolution 6124). 110th United States Congress. 22 May 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e "WIC Farmers' Market Nutrition Program (FMNP)". Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance. Federal Service Desk. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "Food Fight Turmoil at the Memphis Farmers Market exposes flaws in Tennessee’s food-voucher system" Sayle, Hannah. 2011 August 18. Accessed on 7 November 2011

- ^ "Women, Infants and Children Frequently Asked Questions about WIC" Archived 2011-11-25 at the Wayback Machine United States Department of Agriculture undated Accessed 19 November 2011

- ^ Kropf, Mary L., David H. Holben, John P. Holcomb Jr., and Heidi Anderson. 2007. "Food Security Status and Produce Intake and Behaviors of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program Participants." Journal of the American Dietetic Association 107: 1903-1908

- ^ a b Kunkel, Mary E., Barbara Luccia, and Archie C. Moore. 2003. "Evaluation of the South Carolina Seniors Farmers' Market Nutrition Education Program"Journal of the American Dietetic Association 103(7): 880-883

- ^ a b Just, R. E. and Q. Weninger. 1997. “Economic Evaluation of the Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 79: 902-917

- ^ Anderson, J., D. Bybee, R. Brown, D. McLean, E. Garcia, M. L. Breer, and B. Schillo. 20011. "5 A Day Fruit and Vegetable Intervention Improves Consumption in a Low Income Population" Journal of the American Dietetic Association 101(2):195-202

- ^ Conrey, Elizabeth, J., Edward A. Frongillo, Jamie S. Dollahite, and Matthew R. Griffin.2003. "Integrated Program Enhancements Increased Utilization of Farmers' Market Nutrition Program." Journal of Nutrition 133:1841-184

- ^ Dollahite, J. S., J. A. Nelson, E. A. Frongillo, and M. R. Griffin. 2005. “Building Community Capacity Through Enhanced Collaboration in the Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program.” Agriculture and Human Values 22: 339-354.

- ^ "WIC Farmers' Market Nutrition Program (FMNP): Nondiscretionary Provisions of Public Law 108-265, the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004", Federal Register: The Daily Journal of the United States Government. official website. accessed 10 December 2011

- ^ Caines, Roxanne. 2004. "The WIC Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program in Allegheny County: Barriers to Participation and Recommendations for a Stronger Future"

- ^ "The Washington Post" 3 October 2011. Allen, Arthur. "U.S. Touts Fruit and Vegetables while Subsidizing Animals that Become Meat"

- ^ The New York Times 10 May 2007. Kummer, Corby. "Less Green at the Farmers' Market"