Silas Chandler | |

|---|---|

Sergeant A.M. Chandler of the 44th Mississippi Infantry Regiment, Co. F., and Silas Chandler, family slave | |

| Born | 1838 Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | September 1919 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Carpenter |

| Spouse | Lucy Garvin |

| Children | 12 |

Silas Chandler (1838 – September 1919) was an enslaved African American who accompanied his owners, Andrew and Benjamin Chandler, referred to as a "manservant" in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. He was also a carpenter and he helped found and build the first black church in his hometown, West Point, Mississippi.

Early life

Silas was born in 1838 on the Chandler plantation in Virginia. He was moved with the family to Mississippi near the towns of Palo Alto, Mississippi and of West Point, Mississippi at about the age of 2. He was trained as a carpenter. Around 1860 he married Lucy Garvin, although marriages between slaves such as this were not recognized by Mississippi law. Lucy was the child of a mulatto house slave named Polly and an unnamed plantation owner.[1]

Civil War

At the outset of the American Civil War, the Chandlers had 36 slaves. Silas was sent to serve Sergeant Andrew Chandler, who initially enrolled in a company called the Palo Alto Confederates which later became part of Company F of the 44th Mississippi Infantry. Silas' descendants believed that Silas had saved money earned doing odd jobs as a carpenter and attempted to buy his freedom before the war started. However, manumission of Silas was likely illegal under Mississippi law,[nb 1] and some descendants believe Silas may have been defrauded of the money he gave to his Chandler masters in an attempted transaction.[2]

In 1861, Andrew and Silas were photographed together armed and wearing Confederate uniforms; both men held bowie knives and Silas held a rifle which was laid across both of their laps. A pistol was stuffed into Silas' shirt, Andrew was holding another pistol and a third pistol was tucked into Andrew's belt. Most of these weapons were probably photographer's props. Silas's service to Andrew during the war included transporting messages between Andrew and the Chandler family. When Andrew was captured in the Battle of Shiloh, he feared that Silas would also be captured and then be sent to the North where he might be freed.[3]

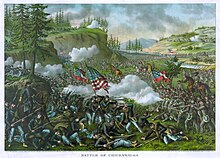

Andrew Chandler was shot in the leg during the 1863 Battle of Chickamauga in Tennessee. Nearly 30% of his regiment were killed or wounded in the battle. The Army surgeon recommended the leg be amputated. Silas may have used a gold coin sewn into his jacket for emergencies to buy a crate of whiskey to bribe the surgeon to let him remove Andrew from the military hospital to be treated elsewhere, and he smuggled Andrew onto a boxcar to Atlanta where they met Andrew's uncle, Kyle Chandler, who brought them back to their home. Another version of the story has Kyle purchasing the whiskey, which may have been for a hometown doctor and not an Army surgeon. Regardless, Silas was instrumental in getting Andrew to Atlanta, away from the Army doctors.[1] Andrew's leg was saved but it never returned to full function. Silas was then sent back to the front to serve as a servant for Andrew's younger brother, Benjamin Chandler, in the 9th Mississippi Cavalry.[3]

Silas was with Benjamin Chandler when he was a part of a detached escort of guards for Confederate President Jefferson Davis when Davis fled Richmond, Virginia. On May 7, 1865, Chandler was a part of that escort which was ordered to disband in order for Davis' escort to be less conspicuous as secrecy became paramount due to the collapse of the Confederacy.[1] Some in the Chandler family later claimed that Silas's service showed his loyalty to the white members of the family, although, others point to his desire to keep in touch with his wife and the birth of his first son, William Henry, during the war as the cause of his loyalty.[3]

After the war

Silas returned to West Point after the war. Silas and Lucy had 12 children, of whom 8 survived childhood: William Henry, Clarence Rufus, Charlie, Robert E., George, Mamie, Willie B., and Sarah. He continued to work as a carpenter and taught the trade to his sons. His family contributed to the building of many homes, churches, banks, and other buildings in the town and throughout the state. In 1868, Silas and other freedmen founded Mount Hermon Baptist Church on land purchased by Silas and his wife Lucy adjacent to his home. Silas purchased and donated the land.[nb 2] Silas Chandler applied for a pension in 1916 which depicts him as a servant rather than a soldier.[3] Andrew Chandler appeared as witness in support of the claim for pension.[4] Silas died in September, 1919, at age 82. His former masters Benjamin and Andrew died in 1909 and 1920 respectively.[1]

Legacy

The relationship between Silas and Andrew and Silas' role in the Confederate Army has long been of interest. In a 1949 newspaper article in the West Point, Mississippi Daily Times includes the photo and gives Silas the title of slave, not soldier. However, by the 1990s, a descendant of Silas's named Bobbie Chandler believed that Silas might have been a soldier—possibly having learned this from a write-up in the neo-Confederate publication, the Southern Partisan.[3]

In 1994, the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy placed a metal cross beside his tomb in West Point, Mississippi to honor his service as a Confederate soldier. One of the catalysts of the 1994 ceremony was the use of the photo in a Washington Times story in the early 1990s. For that story, a copy of the photo was donated by Bobbie Chandler, who was working for the paper. Since the 1994 ceremony, accounts of black Confederate troops surged in popularity, accounts which are held up in defense of the display of Confederate symbols on public land. Also in 1994, an anthology of essays about black Confederate soldiers written by Andrew Chandler Battaille Sr., a descendant of Andrew Chandler, wrote, "It is not difficult to speculate that as a result of sharing these very trying life experiences that a special bond existed between [Andrew and Silas]".[3] In a 2007 book, Clint Johnson calls Silas the most well-recognized black Confederate soldier.[5] As late as 2010, the Corinth Interpretive Center at Shiloh said that during the war, Silas was Andrew's "former slave" and says that "both boys fought together at Chickamauga" and that Silas received a "Mississippi Confederate Veteran Pension", while in reality Silas was a slave during the war and Silas' pension was under the "Application of Indigent Servants of Soldiers and Sailors of the Late Confederacy" and the center later updated its presentation.[6] In 2010, Andrew Chandler Battaile, Jr. had the original tintype of the photo appraised on the TV show, Antiques Roadshow, and later the relationship between Andrew and Silas was featured in the show History Detectives. In the 2000s and 2010s, pro-Confederate websites sold merchandise depicting the pair. The pair continued to be used as an example of black Confederate soldiers at least up until January 2016, where they were used in a syndicated column of the Richmond Times-Dispatch.[3]

Descendants of both Andrew and Silas Chandler have agreed that Chandler was a slave and not a soldier and had the Confederate honors at Silas's grave removed.[3]

Notes

- ^ There were various laws restricting the manumission of slaves. In 1857, there was a "blanket ban" and after 1805, manumission required an act of the state legislature (Klebaner 1955). The 1842 law discussed in the paper the article references may refer to a law from that year outlawing manumission in wills (Mills 2001). Mississippi State Supreme Court Cases Ross v Vertner (1840) accepted manumission by last will and testimate but required the person to emigrate, while Mitchell v Wells (1859) notes the 1842 law and denies the right of manumission (Mills 2001). Sampson & Levin 2012, Coddington 2013, Levin 2014, and Serwer 2016 state that Silas was not freed while serving Andrew and Benjamin during the war, and Sampson & Levin 2012, Levin 2014, and Serwer 2016 state that manumission of Chandler would have been illegal.

- ^ Some believed that this land was given to Silas by his former owners, although this story has been disproved, see Serwer 2016

References

- ^ a b c d Coddington 2013.

- ^ Sampson & Levin 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Serwer 2016.

- ^ "Investigations: Chandler Tintype". History Detectives. Season 9. Episode 12. PBS.

- ^ Johnson 2007.

- ^ Levin 2014.

Bibliography

- Coddington, Ronald S. (September 24, 2013). "A Slave's Service in the Confederate Army". The New York Times Opinionator Blog.

- Johnson, Clint (2007). The Politically Incorrect Guide to The South: (And Why It Will Rise Again). Regnery Publishing. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-59698-616-9.

- Klebaner, Benjamin Joseph (1955). "American Manumission Laws and the Responsibility for Supporting Slaves". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 63 (4): 443–53. JSTOR 4246165.

- Levin, Kevin M. (2014). "Black Confederates Out of the Attic and Into the Mainstream". The Journal of the Civil War Era. 4 (4): 627–35. doi:10.1353/cwe.2014.0073. JSTOR 26062221. S2CID 161822821.

- Levin, Kevin M. (2019). Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War's Most Persistent Myth. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-5326-6.

- Mills, Michael P. (2001). "Slave Law in Mississippi from 1817-1861: Constitutions, Codes and Cases". Mississippi Law Journal. 71: 153.

- Sampson, Myra Chandler; Levin, Kevin M. (February 2012). "The Loyalty of Silas Chandler". Civil War Times. 51 (1): 30–4.

- Serwer, Adam (April 17, 2016). "The Secret History Of The Photo At The Center Of The Black Confederate Myth". BuzzFeed.