The Voyager Golden Records are two identical phonograph records which were included aboard the two Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977.[1] The records contain sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth, and are intended for any intelligent extraterrestrial life form who may find them. The records are a time capsule.

Although neither Voyager spacecraft is heading toward any particular star, Voyager 1 will pass within 1.6 light-years' distance of the star Gliese 445, currently in the constellation Camelopardalis, in about 40,000 years.[2]

Carl Sagan noted that "The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced space-faring civilizations in interstellar space, but the launching of this 'bottle' into the cosmic 'ocean' says something very hopeful about life on this planet."[3]

Background

[edit]The Voyager 1 probe is currently the farthest human-made object from Earth. Both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 have reached interstellar space, the region between stars where the galactic plasma is present.[4] Like their predecessors Pioneer 10 and 11, which featured a simple plaque, both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were launched by NASA with a message aboard—a kind of time capsule, intended to communicate to extraterrestrials a story of the world of humans on Earth.[3]

This is a present from a small, distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.

Contents

[edit]The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University. The selection of content for the record took almost a year. Sagan and his associates assembled 116 images (one used for calibration) and a variety of natural sounds, such as those made by surf, wind, thunder and animals (including the songs of birds and whales). To this they added audio content to represent humanity: spoken greetings in 55 ancient and modern languages, including a spoken greeting in English by U.N. Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim and a greeting by Sagan's six-year-old son, Nick; other human sounds, like footsteps and laughter (Sagan's);[1] the inspirational message Per aspera ad astra in Morse code; and musical selections from different cultures and eras. The record also includes a printed message from U.S. president Jimmy Carter.[5]

The collection of images includes many photographs and diagrams both in black and white, and color. The first images are of scientific interest, showing mathematical and physical quantities, the Solar System and its planets, DNA, and human anatomy and reproduction. Care was taken to include not only pictures of humanity, but also some of animals, insects, plants and landscapes. Images of humanity depict a broad range of cultures. These images show food, architecture, and humans in portraits as well as going about their day-to-day lives. Many pictures are annotated with one or more indications of scales of time, size, or mass. Some images contain indications of chemical composition. All measures used on the pictures are defined in the first few images using physical references that are likely to be consistent anywhere in the universe.

The musical selection is also varied, featuring works by composers such as J.S. Bach (interpreted by Glenn Gould), Mozart, Beethoven (played by the Budapest String Quartet), and Stravinsky. The disc also includes music by Guan Pinghu, Blind Willie Johnson, Chuck Berry, Kesarbai Kerkar, Valya Balkanska, and electronic composer Laurie Spiegel, as well as Azerbaijani folk music (Mugham) by oboe player Kamil Jalilov.[6][7][8][9][10] The inclusion of Berry's "Johnny B. Goode" was controversial, with some claiming that rock music was "adolescent", to which Sagan replied, "There are a lot of adolescents on the planet."[11] The selection of music for the record was completed by a team composed of Carl Sagan as project director, Linda Salzman Sagan, Frank Drake, Alan Lomax, Ann Druyan as creative director, artist Jon Lomberg, ethnomusicologist Robert E. Brown, Timothy Ferris as producer, and Jimmy Iovine as sound engineer.[11][12] It also included the sounds of humpbacked whales from the 1970 album by Roger Payne, Songs of the Humpback Whale.[13]

The Golden Record also carries an hour-long recording of the brainwaves of Ann Druyan.[11] During the recording of the brainwaves, Druyan thought of many topics, including Earth's history, civilizations and the problems they face, and what it was like to fall in love.[14]

After NASA had received criticism over the nudity on the Pioneer plaque (line drawings of a naked man and woman), the agency chose not to allow Sagan and his colleagues to include a photograph of a nude man and woman on the record. Instead, only a silhouette of the couple was included.[15] However, the record does contain "Diagram of vertebrate evolution", by Jon Lomberg, with drawings of an anatomically correct naked male and naked female, showing external organs.[16] The person waving on the diagram was also changed: on the Pioneer plaque, the man is waving, while on the "Vertebrate evolution" image, the woman is waving.

The pulsar map and hydrogen molecule diagram are shared in common with the Pioneer plaque.

The 116 images (one used for calibration) are encoded in analogue form and composed of 512 vertical lines. The remainder of the record is audio, designed to be played at 16+2⁄3 revolutions per minute.

Jimmy Iovine, who was still early in his career as a music producer, served as sound engineer for the project at the recommendation of John Lennon, who was contacted to contribute but was unable to take part.[17]

Sagan's team wanted to include the Beatles 1969 song "Here Comes the Sun" on the record, but the record company EMI, which held the copyrights, declined.[18][19] In the 1978 book Murmurs of Earth, the failure to secure permission for the song is cited as one of the legal challenges faced by the team compiling the Voyager Golden Record.[20] In the book, Sagan said that the Beatles favoured the idea, but "[they] did not own the copyright, and the legal status of the piece seemed too murky to risk."[21] When asked about the obstacle presented by EMI with regard to "Here Comes the Sun", despite the artists' wishes, Ann Druyan said in 2015: "Yeah, that was one of those cases of having to see the tragedy of our planet. Here's a chance to send a piece of music into the distant future and distant time, and to give it this kind of immortality, and they're worried about money ... we got this telegram [from EMI] saying that it will be $50,000 per record for two records, and the entire Voyager record cost $18,000 to produce."[22] However, this was denied in 2017 by Timothy Ferris; in his recollection, "Here Comes the Sun" was not seriously considered for inclusion.[17]

In July 2015, NASA uploaded the audio contents of the record to the audio streaming service SoundCloud.[23][24]

Images

[edit]- Select images on the Voyager Golden Record

-

A woman in a store

-

A photo of Jupiter with its diameter indicated

-

This image depicts humans licking, eating, and drinking as modes of consumption.

-

This is a photograph of the Arecibo Observatory marked with an indication of scale.

-

This image is a photograph of page 6 from Isaac Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica Volume III, De mundi systemate (The system of the world).

-

This is a photograph of Egypt, Red Sea, Sinai Peninsula and the Nile from Earth orbit annotated with chemical composition of Earth's atmosphere.

Playback

[edit]

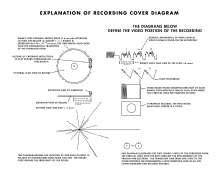

In the upper left-hand corner of the record cover is a drawing of the phonograph record and the stylus carried with it. The stylus is in the correct position to play the record from the beginning. Written around it in binary notation is the correct time of one rotation of the record, 3.6 seconds, expressed in time units of 0.70 billionths of a second, the time period associated with a fundamental transition of the hydrogen atom. The drawing indicates that the record should be played from the outside in. Below this drawing is a side view of the record and stylus, with a binary number giving the time to play one side of the record—about an hour (more precisely, between 53 and 54 minutes).

The information in the upper right-hand portion of the cover is designed to show how pictures are to be constructed from the recorded signals. The top drawing shows the typical signal that occurs at the start of a picture. The picture is made from this signal, which traces the picture as a series of vertical lines, similar to analog television (in which the picture is a series of horizontal lines). Picture lines 1, 2 and 3 are noted in binary numbers, and the duration of one of the "picture lines", about 8 milliseconds, is noted. The drawing immediately below shows how these lines are to be drawn vertically, with staggered "interlace" to give the correct picture rendition. Immediately below this is a drawing of an entire picture raster, showing that there are 512 (29) vertical lines in a complete picture. Immediately below this is a replica of the first picture on the record to permit the recipients to verify that they are decoding the signals correctly. A circle was used in this picture to ensure that the recipients use the correct ratio of horizontal to vertical height in picture reconstruction.[25] Color images were represented by three images in sequence, one each for red, green, and blue components of the image. A color image of the spectrum of the sun was included for calibration purposes.

The drawing in the lower left-hand corner of the cover is the pulsar map previously sent as part of the plaques on Pioneers 10 and 11. It shows the location of the Solar System with respect to 14 pulsars, whose precise periods are given. The drawing containing two circles in the lower right-hand corner is a drawing of the hydrogen atom in its two lowest states, with a connecting line and digit 1 to indicate that the time interval associated with the transition from one state to the other is to be used as the fundamental time scale, both for the time given on the cover and in the decoded pictures.[26]

Manufacturing

[edit]

Blank records were provided by the Pyral S.A. of Créteil, France. CBS Records contracted the JVC Cutting Center in Boulder, Colorado to cut the lacquer masters which were then sent to the James G. Lee record-processing center in Gardena, California to cut and gold-plate eight Voyager records. After the records were plated they were mounted in aluminum containers and delivered to JPL.[27][28]

The record is a copper disk 12 inches (30 cm) in diameter plated first with nickel and then gold.[3] The record's cover is aluminum and electroplated upon it is an ultra-pure sample of the isotope uranium-238. Uranium-238 has a half-life of 4.468 billion years. It is possible (e.g., via mass spectrometry) that a civilization that encounters the record will be able to use the ratio of remaining uranium to the other elements to determine the age of the record.[29]

The records also had the inscription "To the makers of music – all worlds, all times" hand-etched on its surface. The inscription was located in the "takeout grooves", an area of the record between the label and playable surface. Since this was not in the original specifications, the record was initially rejected, to be replaced with a blank disc. Sagan later convinced the administrator to include the record as is.[30]

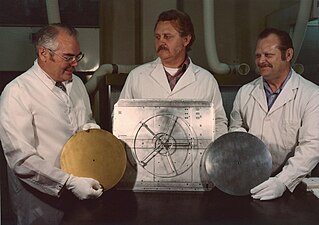

- Manufacturing at the James G. Lee Record Processing center in Gardena, California

-

Phonograph record

-

Recording section

-

Record etching

-

Record etching

-

Gold plating

-

Gold plating

-

Gold plating control

Journey

[edit]

Voyager 1 was launched in 1977, passed the orbit of Pluto in 1990, and left the Solar System (in the sense of passing the termination shock) in November 2004. It is now in the Kuiper belt. In about 40,000 years, it and Voyager 2 will each come to within about 1.8 light-years of two separate stars: Voyager 1 will have approached star Gliese 445, located in the constellation Camelopardalis, and Voyager 2 will have approached star Ross 248, located in the constellation of Andromeda.

In May 2005, it was reported that Voyager 1 had entered the heliosheath,[31] the region beyond the termination shock. The termination shock is where the solar wind, a thin stream of electrically charged gas blowing continuously outward from the Sun, is slowed by pressure from gas between the stars. At the termination shock, the solar wind slows abruptly from its average speed of 300–700 km/s (670,000–1,570,000 mph) and becomes denser and hotter.

In March 2012, Voyager 1 was over 17.9 billion km from the Sun and traveling at a speed of 3.6 AU per year (approximately 61,000 km/h (38,000 mph)), while Voyager 2 was over 14.7 billion km away and moving at about 3.3 AU per year (approximately 56,000 km/h (35,000 mph)).[32]

On September 12, 2013, NASA announced that Voyager 1 had left the heliosheath and entered interstellar space,[33] although it still remains within the Sun's gravitational sphere of influence.

Of the eleven instruments carried on Voyager 1, four are still operational and continue to send back data. It is expected that at least one science instrument will remain operational through 2025 and that engineering data could be transmitted for several more years afterward.[34]

Publications

[edit]Most of the images used on the record (reproduced in black and white), together with information about its compilation, can be found in the 1978 book Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record by Carl Sagan, F. D. Drake, Ann Druyan, Timothy Ferris, Jon Lomberg, and Linda Salzman.[35] A CD-ROM version was issued by Warner New Media in 1992.[36] Author Ann Druyan, who later married Carl Sagan, wrote about the Voyager Record in the epilogue of Sagan's final book Billions and Billions (1997).[37]

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of the record, Ozma Records launched a Kickstarter project to release the record contents in LP format as part of a box set also containing a hardcover book, turntable slipmat, and art print.[38] The Kickstarter was successfully funded with over $1.4 million raised. Ozma Records then produced another edition of the three-disc LP vinyl record box set that also includes the audio content of the Golden Record, softcover book containing the images encoded on the record, images sent back by Voyager, commentary from Ferris, art print, turntable slipmat, and a collector's box. This edition was released in February 2018 along with a 2xCD-Book edition.[39][40] In January 2018, Ozma Records' "Voyager Golden Record; 40th Anniversary Edition" won a Grammy Award for best boxed or limited-edition package.[41]

Track listing

[edit]The track listing is as it appears on the 2017 edition released by Ozma Records.

- Disc one

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Greeting from Kurt Waldheim, Secretary-General of the United Nations" | 0:44 | |

| 2. | "Greetings in 55 Languages" (by Various Artists) | 3:46 | |

| 3. | "United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs" (by Various Artists) | 4:04 | |

| 4. | "The Sounds of Earth" (by Various Artists) | 12:19 | |

| 5. | "Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047: I. Allegro" (by Munich Bach Orchestra/Karl Richter) | Johann Sebastian Bach | 4:44 |

| 6. | "Ketawang: Puspåwarnå (Kinds of Flowers)" (by Pura Paku Alaman Palace Orchestra/K.R.T. Wasitodipuro) | Mangkunegara IV | 4:47 |

| 7. | "Cengunmé" (by Mahi musicians of Benin) | 2:11 | |

| 8. | "Alima Song" (by Mbuti of the Ituri Rainforest) | 1:01 | |

| 9. | "Barnumbirr (Morning Star) and Moikoi Song" (by Tom Djäwa, Mudpo, and Waliparu, recorded by Sandra LeBrun Holmes) | 1:29 | |

| 10. | "El Cascabel" (by Antonio Maciel and Los Aguilillas with Mariachi México de Pepe Villa/Rafael Carrión) | Lorenzo Barcelata | 3:20 |

| 11. | "Johnny B. Goode" | Chuck Berry | 2:41 |

| 12. | "Mariuamangɨ" (by Pranis Pandang and Kumbui of the Nyaura Clan) | 1:25 | |

| 13. | "Sokaku-Reibo (Depicting the Cranes in Their Nest)" (Goro Yamaguchi) | 5:04 | |

| 14. | "Partita for Violin Solo No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006: III. Gavotte en Rondeau" (by Arthur Grumiaux) | Bach | 2:58 |

| 15. | "The Magic Flute (Die Zauberflöte), K. 620, Act II: Hell's Vengeance Boils in My Heart" (by Edda Moser/Bavarian State Opera Orchestra and Chorus/Wolfgang Sawallisch) | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | 3:00 |

| 16. | "Chakrulo" (by Georgian State Merited Ensemble of Folk Song and Dance (Head: Anzor Kavsadze)) | 2:21 |

- Disc two

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Roncadoras and Drums" (by Musicians from Ancash) | 0:55 | |

| 2. | "Melancholy Blues" (by Louis Armstrong and His Hot Seven) | Marty Bloom and Walter Melrose | 3:06 |

| 3. | "Muğam" (by Kamil Jalilov) | 2:35 | |

| 4. | "The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du Printemps), Part II—The Sacrifice: VI. Sacrificial Dance (The Chosen One)" (by Columbia Symphony Orchestra/Igor Stravinsky) | Stravinsky | 4:38 |

| 5. | "The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book II: Prelude and Fugue No. 1 in C Major, BWV 870" (by Glenn Gould) | Bach | 4:51 |

| 6. | "Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Opus 67: I. Allegro Con Brio" (by Philharmonia Orchestra/Otto Klemperer) | Ludwig van Beethoven | 8:49 |

| 7. | "Izlel e Delyu Haydutin" (by Valya Balkanska) | 5:04 | |

| 8. | "Navajo Night Chant, Yeibichai Dance" (Ambrose Roan Horse, Chester Roan, and Tom Roan) | 1:01 | |

| 9. | "The Fairie Round" (by Early Music Consort of London/David Munrow) | Anthony Holborne | 1:19 |

| 10. | "Naranaratana Kookokoo (The Cry of the Megapode Bird)" (by Maniasinimae and Taumaetarau Chieftain Tribe of Oloha and Palasu'u Village Community) | 1:15 | |

| 11. | "Wedding Song" (by young girl from Huancavelica, recorded by John Cohen[42]) | 0:42 | |

| 12. | "Liu Shui (Flowing Streams)" (by Guan Pinghu) | 7:36 | |

| 13. | "Bhairavi: Jaat Kahan Ho" | Kesarbai Kerkar | 3:34 |

| 14. | "Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground" | Blind Willie Johnson | 3:32 |

| 15. | "String Quartet No. 13 in B-flat Major, Opus 130: V. Cavatina (Ludwig van Beethoven)" (by Budapest String Quartet) | by Ludwig van Beethoven | 6:41 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Lafrance, Adrienne (30 June 2017). "Solving the Mystery of Whose Laughter Is On the Golden Record". The Atlantic. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "Voyager – Interstellar Mission". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. January 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Voyager – Golden Record". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ "NASA Spacecraft Embarks on Historic Journey Into Interstellar Space". NASA. September 12, 2013. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ^ Gambino, Megan. "What Is on Voyager's Golden Record?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Anne Kressler. Azerbaijani Music Selected for Voyager Spacecraft Archived 2019-07-03 at the Wayback Machine // Azerbaijan International. — Summer 1994 (2.2). — P. 24-25.

- ^ Natalie Angier. The Canon: The Beautiful Basics of Science. — Faber & Faber, 2009. — P. 408.

- ^ Mike Wehner. You can now buy the NASA audio record that we sent to aliens Archived 2019-07-12 at the Wayback Machine // bgr.com. — November 28th, 2017.

- ^ Aida Huseynova. New images of Azerbaijani Mugham in Twentieth Century // The Music of Central Asia. — Indiana University Press, 2016. — P. 400.

- ^ Margaret Kaeter. Nations in Transitions: The Caucasian Republics. — Infobase Publishing, 2004. — P. 91.

- ^ a b c Gambino, Megan (April 22, 2012). "What Is on Voyager's Golden Record?". The Smithsonian. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ Ferris, Timothy (20 August 2017). "How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made". The New Yorker. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Roth, Mark (1982). "The resounding humpback". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 71 (2): 513. Bibcode:1982ASAJ...71..513R. doi:10.1121/1.387428.

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1997). Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-41160-7.

- ^ Lomberg, Jon, "Pictures of Earth" in Sagan, Carl (1979). Murmurs of Earth. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-34528-396-2.

- ^ "Voyager Record Photograph Index". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ a b Ferris, Timothy (August 20, 2017). "How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made". The New Yorker. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ Deecke, Arved (June 12, 2015). "The Truly Most Expensive Record Ever: 2.5 billion dollars (no Beatles and no nudity)". Kvart & Bølge. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ Shribman, David (July 18, 2019). "Review: The Voyager spacecraft holds a golden record for aliens. 'Vinyl Frontier' tells why". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Phillips, Tony (April 28, 2011). "Voyager, The Love Story". NASA Science. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Sagan, Carl; Drake, Frank D.; Lomberg, Jon; Sagan, Linda Salzman; Druyan, Ann; Ferris, Timothy (1978). Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-41047-5.

- ^ Haskoor, Michael (August 5, 2015). "A Space Jam, Literally: Meet the Creative Director Behind NASA's 'Golden Record,' an Interstellar Mixtape". Vice. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Greetings to the Universe". Retrieved April 20, 2016 – via SoundCloud.

- ^ "Sounds of Earth". Retrieved April 20, 2016 – via SoundCloud.

- ^ Barry, Ron (2017-09-05). "How to decode the images on the Voyager Golden Record". Boing Boing. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ "Voyager Record". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Voyager & the Golden Record". NASA/JPL. 29 October 2015 – via Flickr.

- ^ "Voyager Interstellar Record Collection, 1976-1977" (PDF). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-31.

- ^ "Voyager - Making of the Golden Record". voyager.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2020-03-28.

- ^ Ferris, Timothy (September 5, 2007). "The Mix Tape of the Gods". The New York Times. Retrieved February 11, 2009. The writer of the article claims to have made the inscription.

- ^ "Voyager Enters Solar System's Final Frontier". NASA. May 24, 2005. Archived from the original on May 16, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ "Voyager – The Interstellar Mission". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ "NASA Spacecraft Embarks on Historic Journey Into Interstellar Space". NASA. September 12, 2013. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ "Voyager – Frequently Asked Questions". voyager.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1978). Murmurs of Earth. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-41047-5.

- ^ Sagan, Carl et al. (1992) Murmurs of Earth (computer file): The Voyager Interstellar Record. Burbank: Warner New Media.

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1997). Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium. Random House. ISBN 0-679-41160-7.

- ^ "Voyager Golden Record: 40th Anniversary Edition". Kickstarter. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ Sodomsky, Sam (November 28, 2017). "NASA's Voyager Golden Record Gets New Vinyl Reissue". Pitchfork. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ Andrews, Travis (November 28, 2017). "NASA launched this record into space in 1977. Now, you can own your own copy". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ Cofield, Calla (January 31, 2018). "Reprint of NASA's Golden Record Takes Home a Grammy". Space.com. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Russell, Tony (October 14, 2019). "John Cohen obituary: Film-maker, photographer, folk music revivalist and founder member of the New Lost City Ramblers". The Guardian. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- Originally based on public domain text from the NASA website Archived 2017-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, where selected images and sounds from the record can be found.

External links

[edit]- "The Golden Record". JPL/NASA.