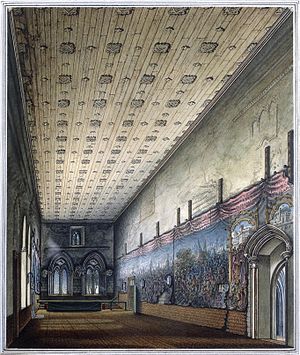

The Great History of Troy tapestries are a lost series of tapestries woven in Flanders around 1475 which were bought by Henry VII of England from Jean, son of Pasquier Grenier, between 1488 and 1490 and hung in the Painted Chamber of Westminster Palace until 1799.[1] Each tapestry contained two or three episodes taken from the Roman de Troie by Benoît de Sainte-Maure.[2] In 1789, notable architects including Robert Adam, James Wyatt, and George Dance the Younger recommended rebuilding Westminster and consequently the tapestries were taken down in 1800 and eventually sold twenty years later. Fourteen years after this sale the Palace of Westminster burned and "it is some consolation to reflect that the tapestries, had they remained, would have shared the same irrevocable fate as the paintings, whereas there is possibly some faint chance that in the clearing of old lumber rooms they may some day come to light, tattered and moth-eaten, but not past preservation, and restored to honour by the veneration of a later age."[3]

Tapestry depictions

The tapestries depicted characters from the story of Troy but in fifteenth-century European dress and the artist John Carter (1748-1817) observed in 1799 that "there is hardly one mark of the Roman or Grecian manners, and but for the name of the several characters engaged in the history written on their dresses, we might conclude the representation related to some eventful period of our own history, where are to be found the circumstances of royal audiences, disembarkation, warriors invoking their patron saint, a monarch in despair, an army on shipboard landing and attacking the wall of a city; a grand battle on land; several knights brought together in a religious building for the purpose of concluding an attack on other powers; a second grand battle; other royal conferences; with a third battle, which concludes this amazing performance."[4]

Henry Currie Marillier (1865-1951) noted that the series "consisted originally of eleven(?) large panels. ... Of sets known to have existed, the finest in all probability was one woven by Pasquier Grenier, of Tournai, [sic, Grenier was a dealer only] and presented to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, by the City of Bruges in 1474. ... A second set was woven for Louis XI of France. ... Most of [the sets] have disappeared. The complete tapestries had French verses running in a label along the top, and Latin distichs below. Few, if any, now have preserved more than fragments of these legends."[5]

Copies

John Carter drew the tapestries in the 1790s and those drawings and the manuscript copies of his letters on the subject to the Gentleman's Magazine made their way into the "Gardner collection of prints, which was sold at Sotheby's in May, 1924, and came into possession of the Westminster Public Library. ... In addition to eight rough sketches of the tapestries -- the five Trojan panels [Plates I, A, B; II, D, E; III, G] and three others -- there are twenty-two large and more highly finished drawings of heads, etc, ..."[6]

Some of the above material is now in Westminster City Archives and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The British Museum and the Yale Center for British Art also have sketches of the Painted Chamber and the tapestries done by Carter.

Provenance and last known location

Sold in 1820 for £10 to Charles Yarnold of Great St. Helen's, London.[7] The tapestries were sold by Yarnold's estate in 1825 to a Mr. Matheman for £7 when they were described as "Plantagenet tapestries." At least five of the tapestries were bought for 60 guineas by a Mr. Teschemacher in 1829 and all the tapestries were subsequently lost.[8] The Teschemacher in question may be a member of the family of James Englebert Teschemacher, who was in London in 1829, removed to Cuba in 1830, and then went to New York City in February 1832 before finally settling in Boston, Massachusetts.

Notes

References

- Binski, Paul. 1986. "The Painted Chamber at Westminster." London: Society of Antiquaries of London. https://archive.org/details/paintedchamberat0000bins/mode/1up

- Brooke, Stephanie. 2022. “ANCESTRY, TRADITION & CONTEXT: The Birth of a Royal Marriage Bed.” Peregrinations 8 (3): 1–32. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=asu&AN=160953147&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Capon, William. 1835. “Notes and Remarks, by the Late Mr William Capon, to Accompany His Plan of the Ancient Palace of Westminster.” Vetusta Monumenta V, 1–7

- Carter, John. 1799. “The Painted Chamber; Plan for a Parliament House.” The Gentleman's Magazine 69, no. 2: 552.

- Carter, John. 1798a. “The Pursuits of Architectural Innovation.” The Gentleman's Magazine 68, no. 2: 764–65.

- Carter, John. 1798b. “The Pursuits of Architectural Innovation 2.” The Gentleman's Magazine 68, no. 2: 824–25.

- Carter, John. 1799b. “The Pursuits of Architectural Innovation 7.” The Gentleman's Magazine 69, no. 1: 92–94.

- Lindfield, Peter N. 2023. "John Carter FSA (1748–1817): A New Corpus of Drawings, and the Painted Chamber." Visual Culture in Britain, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14714787.2022.2094456

- Marillier, H. C. 1925. “The Tapestries of the Painted Chamber; the “Great History of Troy”.” The Burlington Magazine 46, no. 262: 35–42

- Victoria and Albert Museum. 2009. "The walls of the Painted Chamber, Westminster Palace" object record. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O765339/the-walls-of-the-painted-watercolour-drawing-john-carter/