| "The Village Green Preservation Society" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

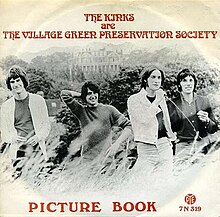

Danish single picture sleeve | ||||

| Song by the Kinks | ||||

| from the album The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society | ||||

| Released | 22 November 1968 | |||

| Recorded | c. 12 August 1968 | |||

| Studio | Pye, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 2:49 | |||

| Label | Pye | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Ray Davies | |||

| Producer(s) | Ray Davies | |||

| The Kinks US chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Official audio | ||||

| "The Village Green Preservation Society" on YouTube | ||||

"The Village Green Preservation Society"[nb 1] is a song by the English rock band the Kinks from their 1968 album The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society. Written and sung by the band's principal songwriter Ray Davies, the song is a nostalgic reflection where the band state their intention to "preserve" British things for posterity. As the opening track, the song introduces many of the LP's themes, and Ray subsequently described it as the album's "national anthem".[4]

Ray was inspired to write "The Village Green Preservation Society" after he heard someone express that the Kinks had been preserving "nice things from the past".[5] Written and recorded in August 1968 as sessions for the band's next album neared completion, the song was intended to be a new title track after he remained unsatisfied with the album's working title Village Green. The song pairs pop and rock music with elements of English music hall, indicating Ray's continued interest in the genre. It has received generally favourable reviews from critics, but later commentators dispute how much of its lyrics were to be considered ironic; some consider them reactionary and others find the tone partially parodic. Coinciding with the band's "God Save the Kinks" promotional campaign, the song was issued as a US single in July 1969, though it failed to chart. The Kinks regularly included the song in their live set list in the 1970s, '80s and '90s.

Background and recording

I was looking for a title for the album [Village Green] about three months ago, when we had finished most of the tracks, and somebody said that one of the things the Kinks have been doing for the last three years is preserving nice things from the past, so I thought I'd write a song which said this ...[5]

Ray Davies composed "The Village Green Preservation Society" around August 1968, after the other eleven songs for the Kinks' next album had been recorded. In a contemporary interview, he explained that the song's central inspiration spawned from a conversation where someone suggested that the Kinks had been preserving "nice things from the past",[5] and he hoped to capture the idea within a single song.[6][7] Ray had been unsatisfied with the LP's working title Village Green but was unsure how to replace it; after composing the song, he re-titled the album The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society.[6]

The Kinks recorded "The Village Green Preservation Society" around 12 August 1968 in Pye Studio 2,[8] one of two basement studios at Pye Records' London offices.[9] Ray is credited as the song's producer,[10] and Pye's in-house engineer Brian Humphries operated the four-track mixing console.[11] The author Andy Miller writes the song's arrangement is defined by Mick Avory's "especially exuberant" drumming and the "similarly light and effective" piano contribution, played by either Ray or session keyboardist Nicky Hopkins.[12][nb 2] Ray's organ contribution is emphasised in the mix over Dave Davies's acoustic rhythm guitar.[15]

Composition

Music and lyrics

The musical composition of "The Village Green Preservation Society" is simple, employing four chords and a midway modulation from C to D major.[12] Miller considers it a pop song,[16] and The Harvard Dictionary of Music characterises it as a rock song with elements of English music hall.[17] The author Patricia Gordon Sullivan considers it one of several songs on Village Green played in the style of music hall, a theme she writes Ray established on the band's 1967 album Something Else by the Kinks.[18] Ray later recalled that though he never went to a music hall performance as a child, his style of composition was heavily influenced by his father, who regularly went to musicals and dances and encouraged his children to sing songs at the piano.[19]

The lyrics of "The Village Green Preservation Society" help establish the themes of Village Green;[20] Ray subsequently described the song as the album's "national anthem".[4] The lyrics state the band's intention to "preserve" things from the past and consists of a listing of institutions to be saved for posterity.[21] Things listed include vaudeville, the George Cross medal and its recipients, draught beer and virginity, among others.[22][nb 3] In addition to "The Village Green Preservation Society", the singers adopt other identifiers, like "the Custard Pie Appreciation Consortium" and "the Skyscraper Condemnation Affiliate".[23] Ray and Dave harmonise closely throughout, and Ray's voice is emphasised at the midway point and its closing.[24] The song concludes with its final lyric "God save the village green!", backed with falsetto harmony vocals.[24]

Interpretation

The lyrics of ... "[The] Village Green Preservation Society" have been discussed often in writing on the Kinks, with the usual intention of finding out just how genuinely nostalgic or how tongue-in-cheek [Ray] Davies was with lines such as "God save little shops, china cups and virginity." Davies's equivocal approach to almost everything – which makes this question interesting in the first place – also makes it, as usual, impossible to answer.[25]

Later commentary regarding "The Village Green Preservation Society" centres around the song's degree of irony.[25] The academic Mark Doyle considers the song emblematic of an ambiguity which characterises Ray's songwriting, holding a tension between both longing for the past and the rejection of longing, leaving it unclear whether the song should be interpreted seriously or satirically.[26][nb 4] He writes that in its tension between being either an earnest call for preservation of English heritage or a satire of traditionalists, Ray's writing forces the listener to evaluate the merits of both positions.[26] Like Doyle, the band biographers Rob Jovanovic and Johnny Rogan each suggest that the song is simultaneously ironic and Ray's sincere expression of love for many of the things listed.[29][nb 5]

Some commentators consider elements of the song reactionary, such as the opposition to office blocks and skyscrapers.[32] Rogan compares the sentiments to the UK Conservation Society's 1966 founding promise to "[fight] against the menace of decreasing standards".[33] Ray countered interpretations that the song was reactionary in a 1984 interview, instead characterising it as "a warm feeling, like a fantasy world that I can retreat to".[34] The author Barry J. Faulk writes that following Ray's November 1968 explanation that the song was meant to capture the Kinks' penchant for preservation, the song's message was meant to directly contrast with that of contemporary rock songs like the Rolling Stones' 1968 single "Street Fighting Man".[35] Miller writes that though it "lack[s] the righteousness and glamour" of the Rolling Stones' single, "The Village Green Preservation Society" is a "quiet song of defiance".[36][nb 6] Doyle considers the band's defiant sentiments an "anti-authoritarian preservationism of the little man",[38] pointing to Dave's later explanation of the song's opening harmonies: "It was like, 'We're impenetrable. We might not have a lot, but you can't kill us. You're going to have to shoot us.'"[39]

"The Village Green Preservation Society" includes elements of autobiography and self-parody.[40] Ray and Dave grew up in Fortis Green, a suburban neighbourhood of Muswell Hill in North London;[41] though the area did not have a traditional village green as a common area,[42] Ray has regularly described the area in rural terms.[43] In a 2009 interview, he explained that "North London was my village green, my version of the countryside", further mentioning Waterlow Park in the nearby suburb of Highgate and its small lake as an influence.[44][45][nb 7] In the two weeks before "The Village Green Preservation Society" was recorded, Ray moved out of his East Finchley semi-detached home on Fortis Green and into a larger Tudor house in the suburbs of Borehamwood, Hertfordshire.[48] In the song, Ray sings for God to save Tudor houses, antique tables and billiards, which Rogan thinks was Ray's self-mockery over his increased social standing.[49] Rogan further suggests "the Anglocentric ideal has already been tainted" by the mention of Donald Duck, an American creation,[50] but cultural researcher Jon Stratton writes Britons could still be nostalgic for the character since he had been popular in Britain since before the Second World War.[51]

Release

Ray sequenced "The Village Green Preservation Society" as the opening track of his original twelve-track edition of The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society.[52] In the United Kingdom, Pye planned to release the album on 27 September 1968, but Ray halted its release in mid-September in order to expand its track listing.[53][nb 8] Pye released the expanded fifteen-track edition of the album in the UK on 22 November 1968, retaining "The Village Green Preservation Society" as the album's opening track.[10] To help promote the album, the Kinks performed the song on 26 November 1968 for BBC Radio 1 programme Saturday Club at the Playhouse Theatre in central London.[10][nb 9] The band also lip-synced the song for ITV programme Time For Blackburn (Pop, People & Places), broadcast on 21 December 1968.[54]

Reprise Records issued "The Village Green Preservation Society" as a US single backed with "Do You Remember Walter?" in July 1969.[nb 10] The single did not chart in America but reached number 19 on Danmarks Radio's chart in Denmark,[58] where the song was instead backed with "Picture Book".[59] The US release coincided with Warner Bros. Records' "God Save the Kinks" promotional campaign, which sought to reestablish the band's status in America after their informal four-year performance ban was lifted in the country.[60] The Kinks' return tour of North America ran from October to December 1969, during which they regularly included "The Village Green Preservation Society" as part of their set list.[61] The song also featured in concerts throughout the 1970s, '80s and '90s.[62]

Reception

In his September 1968 preview of Village Green for New Musical Express, critic Keith Altham was especially fond of the title track, which he thought could have made it to No. 1 in the UK had it been issued as a single.[63] The reviewer for Disc and Music Echo similarly counted it as one of the most memorable songs on the album.[64] In Paul Williams's June 1969 review of the album for Rolling Stone magazine, he praised several elements of the song, including its drums, bass and vocals. He added that "[t]he tune, the rhythm, are more of a delight with each verse", and that it was almost "unbearable" that the song had to finish.[65] Following the song's July 1969 US single release, Cash Box magazine's review staff designated it "Choice Programming" – indicating they thought it deserved the special attention of radio programmers – and the reviewer expected that the band's committed followers would enjoy the song's "cute Anglo-rock effort".[66]

Among retrospective assessors, J. H. Tompkins of the website Pitchfork considered the song an example of Ray's best work, done "with a quiet, ironic smile".[67] Critic Stewart Mason of AllMusic agrees that the song is musically one of Ray's best, but he finds its lyric less effective than the Ray's similarly themed 1967 composition "Autumn Almanac". He adds that though "The Village Green Preservation Society" is likely the best known song from Village Green, the album's cult status means that the song holds a different position from the Kinks' biggest hits, ultimately concluding that other critics may have "slightly overpraised" the song.[15] In a piece for Billboard magazine ranking all of the album's tracks, Morgan Enos placed the song ninth out of fifteen, writing that in spite of its cheerful sound, the song "aches with longing".[68]

Notes

- ^ The original release of Village Green included discrepancies between the titles listed on the album sleeve and those on the LP's central label.[1] The song is titled "The Village Green Preservation Society" on the sleeve, but the LP label omits the The.[2] All subsequent reissues of the album include the The.[3]

- ^ Miller believes Nicky Hopkins played piano since a version the Kinks recorded for the BBC on 26 November 1968 features Ray playing the keyboard with "a somewhat less steady hand".[13] Hinman instead writes Hopkins's last appearance on a Kinks' song was likely around mid-July 1968 on "People Take Pictures of Each Other", before the mid-August recording of "The Village Green Preservation Society".[14]

- ^ Other things listed include strawberry jam, the comic book character Desperate Dan, custard pies, the music hall star Old Mother Riley, the American cartoon character Donald Duck, Mrs Mopp from the BBC's radio wartime comedy programme It's That Man Again, the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, Tudor houses, antique tables and billiards.[22]

- ^ Doyle adds that the confusion over Ray's sincerity often extended to his bandmates.[27] Dave subsequently ascribed the listing of virginity as among the things for preservation to "Ray's purist streak taking things a little too far",[28] leading Doyle to question how Dave missed what Doyle thinks is "obvious sarcasm".[27]

- ^ Doyle compares Ray's writing to a type of ambiguity described by the literary critic William Empson in his 1930 work Seven Types of Ambiguity.[30] In particular, the seventh type occurs "when the two meanings of the word, the two values of the ambiguity, are the two opposite meanings defined by the context so that the total effect is to show a fundamental division in the writer's mind."[31]

- ^ Miller writes that the song's satire has often been overlooked due to the passage of time, and that when understood in the context of the unrest Britain was experiencing in 1968, it is not about escapism but instead mocks the certainty of protesters by producing a list of "idiosyncratic demands".[37]

- ^ In April 1966,[46] local residents founded the Highgate Society, which sought to block plans for construction of a major road through the village, a change which organisers argued would "ruin one of the finest rows of houses" anywhere.[47]

- ^ Release of the twelve-track LP went ahead in Sweden and Norway on 9 October 1968, with subsequent releases of that edition following in France, Italy and New Zealand.[53]

- ^ The performance was later included on the 2001 album The Kinks BBC Sessions 1964–1977.[10]

- ^ Rogan writes the single was released in August 1969,[55] as do Hinman and Jason Brabazon in their self-published band discography.[56] Village Green's 50th anniversary release includes a replica of the 7" single, with notes printed on its sleeve stating it was originally released in July 1969.[57]

References

Citations

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 42.

- ^ Anon.(a) 1968.

- ^ Doggett 1998; Miller & Sandoval 2004; Neill 2018.

- ^ a b Miller 2003, p. 46; Rogan 2015, p. 355.

- ^ a b c

- The Kinks (2014). The Anthology: 1964–1971: "Interview: Ray Davies Talks About Village Green Preservation Society" (CD). Sanctuary, Legacy. Event occurs at 0:17. 88875021542.

- Himes, Geoffrey (11 February 2019). "The Curmudgeon: Ray Davies – Preserving Old, Rural Ways as a Kind of Rebellion". Paste. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022.

- Miller 2003, pp. 46, 148.

- ^ a b Miller 2003, p. 46.

- ^ Dawbarn 1968, p. 8.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 118, 121.

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d Hinman 2004, p. 121.

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 21: (operated four-track); Hinman 2004, p. 124: (Humphries).

- ^ a b Miller 2003, p. 47.

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 47n8.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 117, 118.

- ^ a b Mason, Stewart. "The Village Green Preservation Society – The Kinks". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 58.

- ^ Randel 2003, p. 734.

- ^ Sullivan 2002, pp. 94, 99.

- ^ Miller 2003, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Miller 2003, pp. 50, 58–59; Faulk 2010, p. 118; Hasted 2011, p. 128.

- ^ Faulk 2010, p. 118; Rogan 1998, p. 62.

- ^ a b Jovanovic 2013, p. 149; Rogan 2015, p. 356.

- ^ Doyle 2020, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b Miller 2003, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b Gelbart 2003, pp. 231–232.

- ^ a b Doyle 2020, pp. 15–18.

- ^ a b Doyle 2020, p. 18.

- ^ Davies 1996, p. 107, quoted in Doyle 2020, p. 18.

- ^ Doyle 2020, pp. 15–18; Jovanovic 2013, p. 149; Rogan 2015, p. 356.

- ^ Doyle 2020, p. 16.

- ^ Empson 1953, pp. 192–193, quoted in Doyle 2020, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Hasted 2011, p. 129; Rogan 2015, p. 356.

- ^ MacEwan 1966, p. 31, quoted in Rogan 2015, p. 356.

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 48.

- ^ Faulk 2010, p. 117.

- ^ Miller 2003, pp. 48, 51.

- ^ Miller 2003, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Doyle 2020, p. 129.

- ^ Davies 1996, p. 107, quoted in Doyle 2020, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 51; Rogan 2015, p. 356.

- ^ Kitts 2008, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Fleiner 2017, p. 125; Baxter-Moore 2006, p. 163n3.

- ^ Baxter-Moore 2006, p. 157; Kitts 2008, p. 1.

- ^ McNair, James (18 June 2009). "Ray Davies' well-respected legacy". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022.

- ^ Fleiner 2017, pp. 121, 210.

- ^ Anon. 1966, p. 16.

- ^ Adams, Tim (30 October 2022). "The battle for Highgate: George Michael's old house at centre of face off over 'resort for super-rich'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 118.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 356.

- ^ Rogan 1998, p. 62.

- ^ Stratton 2010, p. 53.

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 39n5.

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 122.

- ^ Rogan 1984, p. 197.

- ^ Hinman & Brabazon 1994, quoted in Davies 1996, p. 273.

- ^ Anon. 2018: "Originally released on Reprise Records, July 1969, as US 7" single 0847."

- ^ "Top 20 – Uge 2". danskehitlister.dk. 29 April 1969. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Anon.(b) 1968.

- ^ Hasted 2011, p. 147.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 351.

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 39; Altham 1968, p. 10.

- ^ Anon.(c) 1968, p. 2.

- ^ Williams 1969.

- ^ Anon. 1969, p. 50.

- ^ Tompkins, J. H. (26 July 2004). "The Kinks: The Village Green Preservation Society". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

- ^ Enos, Morgan (22 November 2018). "'The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society' at 50: Every Song From Worst to Best". Billboard. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022.

Sources

- Altham, Keith (21 September 1968). "Kinks Reminiscing on the Village Green" (PDF). New Musical Express. p. 10 – via WorldRadioHistory.com.

- Anon. (26 April 1966). "London Day by Day: Saving Highgate". The Daily Telegraph. p. 16. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Anon.[a] (1968). The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society (Liner notes). The Kinks. Pye Records. NPL 18233.

- Anon.[b] (1968). "The Village Green Preservation Society" (Liner notes). The Kinks. Pye Records, Mörks Musikförlag. 7N 319-1.

- Anon.[c] (23 November 1968). "Album Reviews". Disc and Music Echo. p. 2.

- Anon. (16 August 1969). "Cash Box Record Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. p. 50 – via WorldRadioHistory.com.

- Anon. (2018). "The Village Green Preservation Society" (Liner notes). The Kinks. BMG, Pye Records. BMGAA09BOX10.

- Baxter‐Moore, Nick (May 2006). "'This Is Where I Belong'—Identity, Social Class, and the Nostalgic Englishness of Ray Davies and the Kinks". Popular Music and Society. 29 (2): 145–165. doi:10.1080/03007760600559989. S2CID 191625359.

- Davies, Dave (1996). Kink: An Autobiography. New York City: Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-7868-6149-1.

- Dawbarn, Bob (30 November 1968). "Looking back with the Kinks: Ray Davies explains The Village Green Preservation Society" (PDF). Melody Maker. p. 8.

- Doggett, Peter (1998). The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society (Liner notes). The Kinks. Essential. ESM CD 481.

- Doyle, Mark (2020). The Kinks: Songs of the Semi-Detached. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-254-9 – via Google Books.

- Empson, William (1953). Seven Types of Ambiguity (3rd ed.). London: Chatto & Windus. OCLC 611436280.

- Faulk, Barry J. (2010). British Rock Modernism, 1967–1977: The Story of Music Hall in Rock. Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4094-1190-1.

- Fleiner, Carey (2017). The Kinks: A Thoroughly English Phenomenon. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3542-7 – via Google Books.

- Gelbart, Matthew (2003). "Persona and Voice in the Kinks' Songs of the Late 1960s". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 128 (2): 200–241. doi:10.1093/jrma/128.2.200. ISSN 0269-0403. JSTOR 3557496.

- Hasted, Nick (2011). The Story of the Kinks: You Really Got Me. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-660-9.

- Hinman, Doug; Brabazon, Jason (1994). You Really Got Me: An Illustrated World Discography of the Kinks, 1964–1993. Rumford, Rhode Island: Doug Hinman. ISBN 978-0-9641005-1-0.

- Hinman, Doug (2004). The Kinks: All Day and All of the Night: Day by Day Concerts, Recordings, and Broadcasts, 1961–1996. San Francisco, California: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-765-3.

- Jovanovic, Rob (2013). God Save the Kinks: A Biography. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-671-0.

- Kitts, Thomas M. (2008). Ray Davies: Not Like Everybody Else. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97768-5 – via the Internet Archive.

- MacEwan, D. M. C. (27 March 1966). "Letters to the Editor: Man and nature". The Observer. p. 31. Retrieved 8 August 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Miller, Andy (2003). The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society. 33⅓ series. New York City: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-8264-1498-4.

- Miller, Andrew; Sandoval, Andrew (2004). The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society (Liner notes). The Kinks. Sanctuary Records. SMETD 102.

- Neill, Andy (2018). The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society (50th Anniversary) (Liner notes). The Kinks. BMG, Pye Records. BMGAA09LP.

- Randel, Don Michael, ed. (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music (Fourth ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01163-2.

- Rogan, Johnny (1984). The Kinks: The Sound and the Fury. London: Elm Tree Books. ISBN 0-241-11308-3.

- Rogan, Johnny (1998). The Complete Guide to the Music of the Kinks. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-6314-6.

- Rogan, Johnny (2015). Ray Davies: A Complicated Life. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-84792-317-2.

- Stratton, Jon (2010). "Englishing Popular Music in the 1960s". In Bennett, Andy; Stratton, Jon (eds.). Britpop and the English Music Tradition. Farnham: Ashgate. pp. 41–54. ISBN 978-0-7546-6805-3.

- Sullivan, Patricia Gordon (2002). "'Let's Have a Go at It': The British Musical Hall and The Kinks". In Kitts, Thomas M. (ed.). Living on a Thin Line: Crossing Aesthetic Borders with The Kinks. Rumford, Rhode Island: Desolation Angel Books. pp. 80–99. ISBN 0-9641005-4-1.

- Williams, Paul (14 June 1969). "The Kinks: The Village Green Preservation Society". Rolling Stone. No. 35. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007.

External links

- "'The Village Green Preservation Society' (Danish single)" at Discogs (list of releases)

- "'The Village Green Preservation Society' (US single)" at Discogs (list of releases)