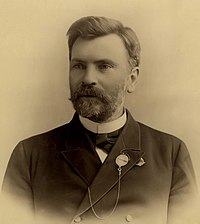

His Excellency | |

|---|---|

Vladimir Kovalevsky | |

| Born | 10 November 1848 |

| Died | 2 November 1935 (aged 86) |

| Resting place | Smolensky Cemetery 59°56′36″N 30°14′55″E / 59.94333°N 30.24861°E |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation(s) | Statesman, scientist and entrepreneur |

| Organization(s) | Institute of Plant Industry, Saint Petersburg State Polytechnical University |

| Known for | Political career in the Russian Empire, works on agricultural topics and agriculturalism, one of the founders of the Saint Petersburg Polytechnic Institute, chairman of the Russian Technical Society |

| Title | Privy Councillor (1899–1917) Actual State Councillor (1891–1899) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | Gregory Vladimirovich Kovalevsky |

| Signature | |

Vladimir Ivanovich Kovalevsky (Russian: Владимир Иванович Ковалевский) (10 November 1848, Novo-Serpukhov, Russian Empire – 2 November 1935, Leningrad, USSR) was a Russian statesman, scientist and entrepreneur. He was the author of numerous articles and works on agricultural themes. From 1892 to 1900, he was the director of the Commerce and Manufacturing Department of the Ministry of Finance of the Russian Empire, and one of the fathers of the concept of Russian protectionism. From 1900 to 1902, he was the Deputy Minister of Finance. From 1906 to 1916, he was the chairman of the Russian Technical Society. Kovalevsky was one of the creators of the Saint Petersburg State Polytechnical University and the Institute of Plant Industry in Leningrad.

Life

Early years

Vladimir Kovalevsky was born to the middle-class family of a retired army major on 9 November 1848, in Novo-Serpukhov (currently Balakliia) in the Zmiyov uyezd of the Kharkov Governorate.[1][2] He was brought up in the Poltava Military School. In August 1865, he entered the Konstantinov Military Academy. In July 1867 he was released into the Derbent 154th Infantry Regiment, serving in the Caucasus.[3] Kovalevsky resigned from military service on 14 May 1868, at the rank of praporschik, equivalent to ensign. In that same year, he began studying at the Saint Petersburg State Polytechnical University, where he was taught by Dmitry Lachinov.[4]

Revolutionary involvement

While studying at the university, Kovalevsky participated in the 1869 student protests, meeting narodnik Sergey Nechayev there. For some time, he attended a group of Nechayev followers in St. Petersburg. In November 1869, Nechayev murdered his former follower I. I. Ivanov, and Kovalevsky gave him an opportunity to stay the night at his house. On 5 January 1870, Kovalevsky was arrested on accusations of sheltering Nechayev, and on 10 September he was transferred to the Peter-Paul Fortress. On 1 July 1871, Kovalevsky was brought to the court of the St. Petersburg judicial chamber on the accusation that without necessarily taking part in the plot to overthrow the existing order of control in Russia,[5] he contributed in providing accommodation for Sergey Nechayev. On 22 August 1871, Kovalevsky was acquitted and released from the Peter-Paul Fortress on that same day.[3] However, he was deprived of being able to work in any government service and was placed under police probation. In 1874, Kovalevsky planned to join the Circle of Tchaikovsky.[6] As a result, he was also subject to a brief arrest relating to the business of Sergey Stepnyak-Kravchinsky.[3]

After release

Once freed, Kovalevsky began living on his parents' property in the Kharkov Governorate. In 1872, however, he once again went to study at the Saint Petersburg Agricultural Institute. Graduating in 1875, Kovalevsky completed his thesis on the theme of "An historical survey on the essence of alcoholic fermentation and the nourishment of yeast" and was honored the degree of Candidate of Agricultural Sciences.[3]

Since 1874, Kovalevsky performed scientific-literary work, printed articles and transcripts in the "Zemledel'cheskaya Gazeta" (Agriculture Gazette) and in the magazine Agriculture and Forestry. In 1879, together with I. O. Levitsky, he published "A statistical description of the milk economy in the northern and central regions of European Russia."

Political career

In 1879, Kovalevsky turned to general Sergei Sykov, his familiar, asking for his assistance in entering the civil service. With the general's backing, it was possible for Kovalevsky to occupy a government position, excluding those only having to do with the teaching activity or work in the prosecution.[3] Later that year, he began working in the statistical division of the Department of Agriculture and Rural Industry of the Imperial Ministry of State Property, where he worked with mapping the soils of European Russia. He also initiated the publishing of annual harvest statistics. In a short period of time, he managed to perfect the wide communication network for obtaining such information.

Since 1882 Kovalevsky was a member of the Agricultural Scientific Committee of the Ministry of State Property. In 1884, by the proposal of Minister of Finance Nikolay Bunge, he transferred his employment to the Ministry of Finance. There he served as vice-director of the Department of Tax Assemblies and participated in the abolition of the poll tax, the conversion of quit-rent from former state serfs, and the introduction of tax inspectors, as well as passing a law to raise the percentage of fees from commercial and industrial enterprises. However, in January 1886, at the request of the Minister of the Interior D. A. Tolstoy, Kovalevsky had to leave the post of vice-director as politically unreliable. Following Bunge's resignation at the end of 1886, the new Minister of Finance, Ivan Vyshnegradsky, offered Kovalevsky for him to take over as an official for special assignments and as a representative of the Ministry of Finance to the Ministry of Railways.[3]

In March 1889, Kovalevsky was appointed a member of the Tariff Committee and the Council on Tariff Matters for the newly formed Department of Rail Affairs, part of the Ministry of Finance, where he met Sergei Witte. In this new role, he worked mainly with tariffs on agricultural goods.[3]

Soon, Kovalevsky became one of the most trusted people around Witte. Their work together continued for more than 13 years. In April 1891, under the introduction of Sergei Witte, Kovalevsky was bestowed the civil rank of "Actual State Councilor". In the end of 1892, Witte became Minister of Finance and offered Kovalevsky to take up the post of director of the Department of Trade and Manufactures. This would mean heading the management of trade and industry in Russia. By October 1892, Vladimir Kovalevsky had worked out a wide-scale, long-term program of commercial-industrial development in Russia, which solved the question of future Russian industrial development coexisting with an extended policy of protectionism. In 1893, Kovalevsky, together with the scientist Dmitri Mendeleev, organized the Bureau of Weights and Measures, and Mendeleev was named its director.

Kovalevsky also headed the commissions for preparing Russian exhibits at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the 1900 World's Fair in Paris. By Kovalevsky's personal initiatives, 1893 saw the beginning of the publication of the "Trade and Industry Gazette" (Russian: Торгово-промышленная газет). In 1896, he developed a project on the position of Russia's commercial schools.[7] He also contributed to the conclusion of trade agreements with Germany and other countries.[8] With Kovalevsky's active involvement, the 1896 All-Russia industrial and art exhibition took place in Nizhniy Novgorod.[9] Later, in 1898, he was involved in the development of a new law on state-industrial taxes. From 1899 to 1901, Kovalevsky was chairman of the Special conference on the preparation of legislation on the establishment of industrial enterprises.

In April 1899, he was bestowed the civil rank of Privy Councillor.

In 1899, along with Sergey Witte, Dmitry Mendeleev and others, Kovalevsky helped organize the Saint Petersburg State Polytechnical University.[10]

In 1900, he was appointed Deputy to the Minister of Finance, having power over matters of trade and industry.

Fake promissory notes and resignation

A serious blow to Kovalevsky's career was dealt by a scandalous affair involving fake promissory notes. Back in 1896, he met the actress and entrepreneur Elizaveta Shabel'skaya, and they had an affair. But in 1902, he became interested in Maria Ilovayskaya and accused his former lover of faking promissory notes in his name. The controversy dragged on until 1905. To marry Ilovayskaya, Kovalevsky divorced his wife, Ekaterina Lukhutina, on the premise of her unfaithfulness. With that, he promised to the consistory, under the oath, that he never failed to perform his conjugal responsibilities. His wife, however, accused him of lying and perjury, and in order not to discredit the Ministry of Finance, Kovalevsky was forced to resign as Deputy Finance Minister in 1902.[11][12] His duties in the Ministry of Finance were filled by Vassily Timiryazev.

After resignation

In 1904 Kovalevsky became a member of the Council (Soviet) of Ural Mountains Developers' Congresses, and until October 1905, he was the Council's representative in Saint Petersburg. In that same year, he was also one of the organizers of the Council of Congresses of Representatives of Trade and Industry. It is also known that Kovalevsky disapproved of Pyotr Stolypin's agrarian politics, and showed that by turning down an invitation to meet him.[3] In 1909, Kovalevsky was chosen to be the chairman of a convention against alcoholism.[13] In that same year, he became the chair of the administration of the Saint Petersburg Rail Car Factory Union, and in 1913, of the Ural-Caspian Petroleum Society. In 1914, he was head of the Society of Mechanical Factories "Brothers of Bromley". From 1903, he was the deputy chairman of the Russian Technical Society, and on 2 December 1906, he was elected Chairman. Kovalevsky carried this duty until 23 January 1916. During World War I, Kovalevsky was a member of a bureau of the Central Military Industrial Committee and chairman of the Peat Committee of the General Directorate of Land Management and Agriculture.

After the revolution

After the October Revolution, Kovalevsky stayed in Russia and worked in several central scientific agricultural establishments: from 1919 to 1929[14] he occupied the post of Chairman of the Scientific Committee of the Narkomzem - the country's foremost scientific center in agronomy and agriculture, and from 1923, he was the Honorable Chairman of the Scientific Council of the Institute of Plant Industry. There he worked with Nikolay Vavilov. In 1923, Kovalevsky was appointed chairman of the Scientific-Technical Council of the First All-Union Agriculture and Orchard Industry Exhibition in Moscow. He worked on the project of creating the USSR VDNKh. During the course of several years, Kovalevsky was the senior editor of the Great Agricultural Encyclopedia, which was one of the most complete worldwide publications of that type.

In November 1928, in the Mariinsky Palace in Leningrad, he celebrated his eightieth birthday. Due to this notable date, he was recognized as Honored Worker of Science and Technology of the RSFSR. Vladimir Kovalevsky died on 2 November 1935 from pulmonary edema, having not lived to his 86th birthday by a week. He was buried at the Smolensk Cemetery.

Personal life

Vladimir Kovalevsky was married twice. His first wife was E. N. Lukhutina,[6] whom he married in 1872 (date unknown), and his second was M. G. Ilovayskaya (born Blagosvetlova), married 1903. Ilovayskaya was the wife of a famous critic and publicist, editor of the Russkoye Slovo ("Russian Word") and Delo ("Business") magazines, Gregory Blagosvetlov. His first marriage proved unsuccessful. In 1902, Kovalevsky became involved in a lawsuit against Elizaveta Shabel'skaya, his former lover, after which he divorced Lukhutina. All of this led a to scandal which ended his political career.

Kovalevsky remarried in 1903. With this second marriage, he had a son Georgiy (1905–1942), who became a botanist and worked with Nikolay Vavilov at the Institute of Plant Industry. He died of starvation during the Blockade of Leningrad in 1942.

Residences

- 96/38, Kamennoostrovsky Pereulok, Saint Petersburg;[15]

- 57 Gertsen Street, Leningrad.[1]

Scientific work

From 1881 to 1917, Vladimir Kovalevsky annually published statistical summaries about the harvests of wheat and other staples in Russia in the "Agricultural Gazette" and in the "Agriculture and Forestry" magazine. Nikolay Vavilov characterized these summaries as the "foundation of agricultural knowledge in Russia".[1] Kovalevsky was a supporter of using geographical principles in agriculture. In 1884, Kovalevsky was able to establish laws governing the shortening of the growing season of bread grains as a way of advancing agriculture to the north. These laws were called the Kovalevsky Laws and played an important practical role.[1][16] Kovalevsky was one of the founders of agricultural ecology, whose challenges he identified as such: "Explanation of joint interaction on the harvest quality of grain, constitutions of the soils, methods of working the land, meteorological conditions, protection of plants, etc.".[1] He claimed that "the harvest, or the productivity in general, is not a constant amount, but the result of interaction of the productivity and survivability of plants with unfavorable conditions of the outside environment".[1]

Also, Kovalevsky studied the effect of meteorological, hydrological, and temperature factors on harvest. He supported the use of science, especially physics, when determining the effects of climate and weather on plant development. In 1889, at the third All-Russia Congress of Natural Scientists, Kovalevsky spoke on this matter with a report titled "Queries of modern agriculture to natural science". By his initiative, special weather stations were set up in different regions of Russia, and Kovalevsky has been called one of the founders of agricultural meteorology.[1] In 1932, academic Abram Ioffe and Kovalevsky organized the Leningrad Institute of Agrophysics.

At the end of the 1920s, Kovalevsky became a member of the International Meteorological Organization.[1] He was also a member of the Free Economic Society and the Russian Geographical Society.

During his work, Kovalevsky paid considerable attention to peasant labor. He believed that peasants were, by nature, ecologists, and that their traditions and experience must be taken into consideration.

Many practical tips and recommendations are found in Kovalevsky's works which are still applicable today. For example, suggestions are found about growing rice and tea, cultivation of dry land, anti-desertification measures, and beekeeping. He was also decisively opposed to using excess mineral fertilizer.[1]

Following Kovalevsky's recommendations, pine trees were planted on the slopes of dunes in the Sestroretsk region near Saint Petersburg, which saved a row of villages and a small factory from the advancing sands.[1]

Evaluation of accomplishments

During the ten years when Kovalevsky was head of Russian industrial development, the size of industrial production in the Russian Empire doubled. One of the authors of legislation on commercial and polytechnic education, Vladimir Kovalevsky actively supported the creation of educational institutions of the new type. In all, in cooperation with Kovalevsky, over 100 new professional schools of various types, 73 commerce schools, several liberal arts schools, and 35 new commercial maritime schools were established.[1] The largest of these establishments were the Saint Petersburg Polytechnic Institute, Kiev Polytechnic Institute, and Warsaw University of Technology.

All of Vladimir Ivanovich [Kovalevsky's] work is noted with features of bright talent, lively initiative, a rare versatility of erudition and an extraordinary capacity for work... With the gift to inspire his coworkers and companions, Vladimir Ivanovich, in each case, took the lion's share of work upon himself.[1]

— Nikolai Kuznetsov

Primary works

- "A Statistical description of the dairy industry in central and northern European Russia" (Russian: Статистический очерк молочного хозяйства в северной и средних полосах Европейской Россиi) (1879, with I. O. Levitsky);

- "The Origins of the culture and technical processing of sugar sorghum" (Russian: Основы культуры и технической переработки сахарного сорго) (1883);

- "Industry and Trade of Russia" (Russian: Промышленность и торговля России), part of the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary;

- "Growing season length of cultural plants depending on latitude and the longitude". Works of the Saint Petersburg Society of Natural Scientists (XV ed.). СПб. 1884. pp. 15–22.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - with P. P. Semeonov (1893). Siberia and the Great Siberian Railway: with a general map. Saint Petersburg. p. 265.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Popular Education at the All-Russian Exhibition of Nizhny Novgorod. 1896.[17]

- From Old Notes and Recollections. "Russian Past" - Русское прошлое.Historical-Documentative Almanac. 1991. pp. 26–55.

- From Recollections about Graf Sergei Yulievich Witte. "Russian Past" - Русское прошлое.Historical-Documentative Almanac. 1991. pp. 55–84.

He also contributed many articles about various agricultural topics to the Agriculture and Forestry and Agricultural Gazette magazines. Under his editing, the Ministry of Finance published "Production Powers of Russia" (Russian: Производительные силы России) (1896) and "Russia at the End of the 19th Century" (Russian: Россия в конце XIX века) (1900).

Translated works

- Emil von Wolff, "Rational feeding of agricultural animals by the newest physiological findings" (Russian: Рациональное кормление сельскохозяйственных животных по новейшим физиологическим исследованиям) (1875).

- Wilhelm Fleischmann, "Milk and the dairy business" (Russian: Молоко и молочное дело) (1879—1880).

- Gottlieb Haberlandt, "General agricultural plant-growing" (Russian: Общее сельскохозяйственное растениеводство) (1879—1880).

- F. Prosch, "Breeding of large livestock and its caretaking" (Russian: Выращивание крупного рогатого скота и уход за ним) (1881).

- Alexander von Middendorff, "Descriptions of the Fergana Valley" (Russian: Очерки Ферганской долины) (1882).

- Girolamo Azzi, "Agricultural ecology" (Russian: Сельскохозяйственная экология) (1928).

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Isayev, V. A. "V. I. Kovalevsky: almost no one knows his name". Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ Shepelev, L. E. (1991). Recollections of V. I. Kovalevsky (in Russian). "Russian Past" - Русское прошлое. pp. 5–21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shepelev, L. E. (1991). Recollections of V. I. Kovalevsky. "Russian Past" - Русское прошлое. Historical-Documentative Almanac. pp. 5–21.

- ^ РГИА, ф. 387, оп .5, д. 31369, л. 49—56; Обращение председатель ИРТО 7 июня 1889 года П. А. Кочубея к товарищу министра государственных имуществ В. И. Вешнякову.

- ^ Peter Kropotkin (1901). "The Present Crisis in Russia". The North American Review.

- ^ a b "Volume 2. The seventies. Lukhutina, Ekaterina Nikitichna". Figures of the revolutionary movement in Russia: Biobibliographical dictionary - From the predecessors of the Decembrists to the fall of czarism. Moscow: All-Union Society of political prisoners and forced migrants - Publishing house. 1930.

- ^ "The immortal and eternal profession - Merchant" (in Russian). "Devichnik" - Девичник.

- ^ Fedorchenko, V. (2003). "Volume 2". The Imperial House: Eminent Dignitaries (in Russian). Moscow: Olma Media Group. pp. 552, 638. ISBN 9785786700467.

- ^ Stepanov, A. "Kovalevsky Vladimir Ivanovich". Encyclopedia of the Russian People (Энциклопедия Русского Народа).

- ^ "Saint Petersburg State Polytechnical University, Chronology". Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ^ Zubarev, D. (2007). "Word and Deed: The letters of E. A. Shabelski from the archives of the Police Department". "NLO" - НЛО.

- ^ Makarova, O. (2007). ""Well, if Suvorin, who invented it, turned away ...": The case of Shabelski and participation of the publisher "Novoye Vremya"". "NLO" - НЛО.

- ^ Works of first All-Russian Congress to combat alcoholism. 1910.

- ^ Vernadsky, V. I. (2006). "1937". Diaries. 1935—1941. Moscow. Archived from the original on 2008-12-07. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Platonov, O. A. (1996). The crown of thorns of Russia. The Secret History of Freemasonry 1731 - 1996 (2nd, edited and expanded ed.). Moscow: "Rodnik" - Родник. p. 704.

- ^ Goncharov, N. P. (2007). "To the 120-th birthday of N. I. Vavilov" (PDF). "Vestnik VOGiS" - Вестник ВОГиС.

- ^ Peter Kropotkin (1902). "Russian Schools and the Holy Synod".

The proof of this may be found in an official publication, which I have before me on my table. I mean the work issued in Russia, in 1896, by order of the Ministry of Public Instruction, under this title: Popular Education at the All-Russian Exhibition of Nizhny Novgorod, published by the Head of the Education Department of the Exhibition, [Vladimir] Kovalevsky.

Further reading

- Ковалевский Владимир Иванович (15А (30) ed.). Энциклопедический Словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона. 1895.

- Ковалевский Владимир Иванович (дополнение к статье) (3 ed.). Энциклопедический Словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона. 1907.

- А. Степанов. Ковалевский Владимир Иванович. Энциклопедия Русского Народа.

- L. E. Shepelev. (1991). "Титулы и форменная одежда чиновников гражданского ведомства, Гражданские чины". In редактор чл.-кор. А.Н. СССР Б. В. Ананьин (ed.). Титулы, мундиры, ордена в Российской империи. М.: Наука (Ленинградское отделение). p. 221.

- В. А. Исаев (2008). В. И. Ковалевский: имени его почти не знают... Первое сентября.

- С.Ю. Витте (1960). "Глава 11". Воспоминания. М. p. 189.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Е. Б. Гинак (1994). Роль В. И. Ковалевского в создании Главной палаты мер и весов. СПб: Труды и доклады научной конференции «Владимир Иванович Ковалевский (1848—1934)».

- L. E. Shepelev (1991). Recollections of V. I. Kovalevsky (2 ed.). "Russian Past" - Русское прошлое.Historical-Documentative Almanac. pp. 5–21.

- Н. И. Вавилов (1935). Памяти В. И. Ковалевского (1 ed.). Природа. pp. 88–89.

- В. М. Дорошевич (1905). В. И. Ковалевский (Воспоминание журналиста) (Собрание сочинений) (IV.Литераторы и общественные деятели. ed.). М.: Товарищество И. Д. Сытина. p. 171.

- Н. Е. Врангель (2003). "Глава 5". Воспоминания. От крепостного права до большевиков. М.: Новое литературное обозрение. p. 512. ISBN 5-86793-223-0.