The war of the currents was a series of events surrounding the introduction of competing electric power transmission systems in the late 1880s and early 1890s. It grew out of two lighting systems developed in the late 1870s and early 1880s; arc lamp street lighting running on high-voltage alternating current (AC), and large-scale low-voltage direct current (DC) indoor incandescent lighting being marketed by Thomas Edison's company.[1] In 1886, the Edison system was faced with new competition: an alternating current system initially introduced by George Westinghouse's company that used transformers to step down from a high voltage so AC could be used for indoor lighting. Using high voltage allowed an AC system to transmit power over longer distances from more efficient large central generating stations. As the use of AC spread rapidly with other companies deploying their own systems, the Edison Electric Light Company claimed in early 1888 that high voltages used in an alternating current system were hazardous, and that the design was inferior to, and infringed on the patents behind, their direct current system.

In the spring of 1888, a media furor arose over electrical fatalities caused by pole-mounted high-voltage AC lines, attributed to the greed and callousness of the arc lighting companies that operated them. In June of that year Harold P. Brown, a New York electrical engineer, claimed the AC-based lighting companies were putting the public at risk using high-voltage systems installed in a slipshod manner. Brown also claimed that alternating current was more dangerous than direct current and tried to prove this by publicly killing animals with both currents, with technical assistance from Edison Electric. The Edison company and Brown colluded further in their parallel goals to limit the use of AC with attempts to push through legislation to severely limit AC installations and voltages. Both also colluded with Westinghouse's chief AC rival, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company, to make sure the first electric chair was powered by a Westinghouse AC generator.

By the early 1890s, the war was winding down. Further deaths caused by AC lines in New York City forced electric companies to fix safety problems. Thomas Edison no longer controlled Edison Electric, and subsidiary companies were beginning to add AC to the systems they were building. Mergers reduced competition between companies, including the merger of Edison Electric with their largest competitor, Thomson-Houston, forming General Electric in 1892. Edison Electric's merger with their chief alternating current rival brought an end to the war of the currents and created a new company that now controlled three quarters of the US electrical business.[2][3] Westinghouse won the bid to supply electrical power for the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893 and won the major part of the contract to build Niagara Falls hydroelectric project later that year (partially splitting the contract with General Electric). DC commercial power distribution systems declined rapidly in numbers throughout the 20th century; the last DC utility in New York City was shut down in 2007.[4]

Background

The war of the currents grew out of the development of two lighting systems; arc lighting running on alternating current and incandescent lighting running on direct current.[1] Both were supplanting gas lighting systems, with arc lighting taking over large area/street lighting, and incandescent lighting replacing gas for business and residential indoor lighting.

Arc lighting

By the late 1870s, arc lamp systems were beginning to be installed in cities, powered by central generating plants. Arc lighting was capable of lighting streets, factory yards, or the interior of large buildings. Arc lamp systems used high voltages (above 3,000 volts) to supply current to multiple series-connected lamps,[5] and some ran better on alternating current.[6]

1880 saw the installation of large-scale arc lighting systems in several US cities including a central station set up by the Brush Electric Company in December 1880 to supply a 2-mile (3.2 km) length of Broadway in New York City with a 3,500–volt demonstration arc lighting system.[7][8] The disadvantages of arc lighting were: it was maintenance intensive, buzzed, flickered, constituted a fire hazard, was really only suitable for outdoor lighting, and, at the high voltages used, was dangerous to work with.[9]

Edison's direct current company

In 1878 inventor Thomas Edison saw a market for a system that could bring electric lighting directly into a customer's business or home, a niche not served by arc lighting systems.[11] By 1882 the investor-owned utility Edison Illuminating Company was established in New York City. Edison designed his utility to compete with the then established gas lighting utilities, basing it on a relatively low 110-volt direct current supply to power a high resistance incandescent lamp he had invented for the system. Edison direct current systems would be sold to cities throughout the United States, making it a standard with Edison controlling all technical development and holding all the key patents.[12] Direct current worked well with incandescent lamps, which were the principal load of the day. Direct-current systems could be directly used with storage batteries, providing valuable load-leveling and backup power during interruptions of generator operation. Direct-current generators could be easily paralleled, allowing economical operation by using smaller machines during periods of light load and improving reliability. Edison had invented a meter to allow customers to be billed for energy proportional to consumption, but this meter worked only with direct current. Direct current also worked well with electric motors, an advantage DC held throughout the 1880s. The primary drawback with the Edison direct current system was that it ran at 110 volts from generation to its final destination giving it a relatively short useful transmission range: to keep the size of the expensive copper conductors down generating plants had to be situated in the middle of population centers and could only supply customers less than a mile from the plant.

Westinghouse and alternating current

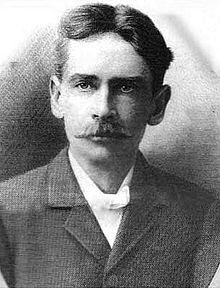

In 1884 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania inventor and entrepreneur George Westinghouse entered the electric lighting business when he started to develop a DC system and hired William Stanley, Jr. to work on it. In 1885 he read an article in UK technical journal Engineering that described alternating current systems under development.[13] By that time alternating current had gained a key advantage over direct current with the development of transformers that allowed the voltage to be "stepped up" to much higher transmission voltages and then dropped down to a lower end user voltage for business and residential use.[14] The high voltages allowed a central generating station to supply a large area, up to 7-mile (11 km) long circuits.[15] Westinghouse saw this as a way to build a truly competitive system instead of simply building another barely competitive DC lighting system using patents just different enough to get around the Edison patents.[16] The Edison DC system of centralized DC plants with their short transmission range also meant there was a patchwork of un-supplied customers between Edison's plants that Westinghouse could easily supply with AC power.

In 1885 Westinghouse purchased the US patents rights to a transformer developed by French engineer Lucien Gaulard (financed by British engineer John Dixon Gibbs). He imported several of these "Gaulard–Gibbs" transformers as well as Siemens AC generators to begin experimenting with an AC-based lighting system in Pittsburgh.[17] That same year William Stanley used the Gaulard-Gibbs design and designs from the Hungarian Ganz company's Z.B.D. transformer to develop the first practical transformer.[18] The Westinghouse Electric Company was formed at the beginning of 1886.

In March 1886 Stanley, with Westinghouse's backing, installed the first multiple-voltage AC power system, a demonstration incandescent lighting system, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts.[19] Expanded to the point where it could light 23 businesses along main street with very little power loss over 4000 feet, the system used transformers to step 500 AC volts at the street down to 100 volts to power incandescent lamps at each location.[20] By fall of 1886 Westinghouse, Stanley, and Oliver B. Shallenberger had built the first commercial AC power system in the US in Buffalo, New York.

The spread of AC

By the end of 1887 Westinghouse had 68 alternating current power stations to Edison's 121 DC-based stations. To make matters worse for Edison, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company of Lynn, Massachusetts (another competitor offering AC- and DC-based systems) had built 22 power stations.[10] Thomson-Houston was expanding their business while trying to avoid patent conflicts with Westinghouse, arranging deals such as coming to agreements over lighting company territory, paying a royalty to use the Stanley AC transformer patent, and allowing Westinghouse to use their Sawyer-Man incandescent bulb patent. Besides Thomson-Houston and Brush there were other competitors at the time, including the United States Illuminating Company and the Waterhouse Electric Light Company. All of the companies had their own electric power systems, arc lighting systems, and even incandescent lamp designs for domestic lighting, leading to constant lawsuits and patent battles between themselves and with Edison.[21]

Safety concerns

Elihu Thomson of Thomson-Houston was concerned about AC safety and put a great deal of effort into developing a lightning arrestor for high-tension power lines as well as a magnetic blowout switch that could shut the system down in a power surge, a safety feature the Westinghouse system did not have.[22] Thomson also worried about what would happen with the equipment after they sold it, assuming customers would follow a risky practice of installing as many lights and generators as they could get away with. He also thought the idea of using AC lighting in residential homes was too dangerous and had the company hold back on that type of installation until a safer transformer could be developed.[23]

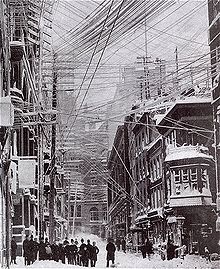

Due to the hazards presented by high voltage electrical lines most European cities and the city of Chicago in the US required them to be buried underground.[24] The City of New York did not require burying and had little in the way of regulation so by the end of 1887 the mishmash of overhead wires for telephone, telegraph, fire and burglar alarm systems in Manhattan were now mixed with haphazardly strung AC lighting system wires carrying up to 6,000 volts.[25] Insulation on power lines was rudimentary, with one electrician referring to it as having as much value "as a molasses covered rag", and exposure to the elements was eroding it over time.[24] A third of the wires were simply abandoned by defunct companies and slowly deteriorating, causing damage to, and shorting out the other lines. Besides being an eyesore, New Yorkers were annoyed when a large March 1888 snowstorm (the Great Blizzard of 1888) tore down a large number of the lines, cutting off utilities in the city. This spurred on the idea of having these lines moved underground but it was stopped by a court injunction obtained by Western Union. Legislation to give all the utilities 90 days to move their lines into underground conduits supplied by the city was slowly making its way through the government but that was also being fought in court by the United States Illuminating Company, who claimed their AC lines were perfectly safe.[25][26]

Edison's anti-AC stance

As AC systems continued to spread into territories covered by DC systems, with the companies seeming to impinge on Edison patents including incandescent lighting, things got worse for the company. The price of copper was rising, adding to the expense of Edison's low voltage DC system, which required much heavier copper wires than higher voltage AC systems. Thomas Edison's own colleagues and engineers were trying to get him to consider AC. Edison's sales force was continually losing bids in municipalities that opted for cheaper AC systems[27] and Edison Electric Illuminating Company president Edward Hibberd Johnson pointed out that if the company stuck with an all DC system it would not be able to do business in small towns and even mid-sized cities.[28] Edison Electric had a patent option on the ZBD transformer, and a 1886 confidential in-house report by electrical engineer Frank Sprague had recommended that the company go AC, but Thomas Edison was against the idea.[29][30]

After Westinghouse installed his first large scale system, Edison wrote in a November 1886 private letter to Edward Johnson, "Just as certain as death Westinghouse will kill a customer within six months after he puts in a system of any size, He has got a new thing and it will require a great deal of experimenting to get it working practically."[31] Edison seemed to hold a view that the very high voltage used in AC systems was too dangerous and that it would take many years to develop a safe and workable system.[29] Safety and avoiding the bad press of killing a customer had been one of the goals in designing his DC system[32] and he worried that a death caused by a mis-installed AC system could hold back the use of electricity in general.[29] Edison's understanding of how AC systems worked seemed to be extensive. He noted what he saw as inefficiencies and that, combined with the capital costs in trying to finance very large generating plants, led him to believe there would be very little cost savings in an AC venture.[33] Edison was also of the opinion that DC was a superior system (a fact that he was sure the public would come to recognize) and inferior AC technology was being used by other companies as a way to get around his DC patents.[34]

In February 1888 Edison Electric president Edward Johnson published an 84-page pamphlet titled "A Warning from the Edison Electric Light Company" and sent it to newspapers and to companies that had purchased or were planning to purchase electrical equipment from Edison competitors, including Westinghouse and Thomson-Houston, stating that the competitors were infringing on Edison's incandescent light and other electrical patents.[35] It warned that purchasers could find themselves on the losing side of a court case if those patents were upheld. The pamphlet also emphasized the safety and efficiency of direct current, with the claim DC had not caused a single death, and included newspaper stories of accidental electrocutions caused by alternating current.[citation needed]

Execution by electricity

As arc lighting systems spread, so did stories of how the high voltages involved were killing people, usually unwary linemen, a strange new phenomenon that seemed to instantaneously strike a victim dead.[36] One such story in 1881 of a drunken dock worker dying after he grabbed a large electric dynamo led Buffalo, New York dentist Alfred P. Southwick to seek some application for the curious phenomenon.[37] He worked with local physician George E. Fell and the Buffalo ASPCA, electrocuting hundreds of stray dogs, to come up with a method to euthanize animals via electricity.[38] Southwick's 1882 and 1883 articles on how electrocution could be a replacement for hanging, using a restraint similar to a dental chair (an electric chair)[39] caught the attention of New York State politicians who, following a series of botched hangings, were desperately seeking an alternative. An 1886 commission appointed by New York governor David B. Hill, which including Southwick, recommended in 1888 that executions be carried out by electricity using the electric chair.[40]

There were early indications that this new form of execution would become mixed up with the war of currents. As part of their fact-finding, the commission sent out surveys to hundreds of experts on law and medicine, seeking their opinions, as well as contacting electrical experts, including Elihu Thomson and Thomas Edison.[41] In late 1887, when death penalty commission member Southwick contacted Edison, the inventor stated he was against capital punishment and wanted nothing to do with the matter. After further prompting, Edison hit out at his chief electric power competitor, George Westinghouse, in what may have been the opening salvo in the war of currents, stating in a December 1887 letter to Southwick that it would be best to use current generated by "'alternating machines,' manufactured principally in this country by Geo. Westinghouse".[42] Soon after the execution by electricity bill passed in June 1888, Edison was asked by a New York government official what means would be the best way to implement the state's new form of execution. "Hire out your criminals as linemen to the New York electric lighting companies" was Edison's tongue-in-cheek answer.[43][44]

Anti-AC backlash

As the number of deaths attributed to high voltage lighting around the country continued to mount, a cluster of deaths in New York City in the spring of 1888 related to AC arc lighting set off a media frenzy against the "deadly arc-lighting current"[45] and the seemingly callous lighting companies that used it.[46][47] These deaths included a 15-year-old boy killed on April 15 by a broken telegraph line that had been energized with alternating current from a United States Illuminating Company line; a clerk killed two weeks later by an AC line; and a Brush Electric Company lineman killed in May by the AC line he was cutting. The press in New York seemed to switch overnight from stories about electric lights vs gas lighting to "death by wire" incidents, with each new report seeming to fan public resentment against high voltage AC and the dangerously tangled overhead electrical wires in the city.[25][46]

Harold Brown's crusade

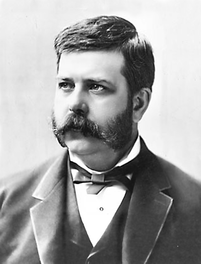

At this point an electrical engineer named Harold P. Brown, who at that time seemed to have no connection to the Edison company,[48] sent a June 5, 1888 letter to the editor of the New York Post claiming the root of the problem was the alternating current (AC) system being used. Brown argued that the AC system was inherently dangerous and "damnable" and asked why the "public must submit to constant danger from sudden death" just so utilities could use a cheaper AC system.

At the beginning of attacks on AC, Westinghouse, in a June 7, 1888 letter, tried to defuse the situation. He invited Edison to visit him in Pittsburgh and said "I believe there has been a systemic attempt on the part of some people to do a great deal of mischief and create as great a difference as possible between the Edison Company and The Westinghouse Electric Co., when there ought to be an entirely different condition of affairs". Edison thanked him but said "My laboratory work consumes the whole of my time".[49]

On June 8, Brown was lobbying in person before the New York Board of Electrical Control, asking that his letter to the paper be read into the meeting's record and demanding severe regulations on AC including limiting voltage to 300 volts, a level that would make AC next to useless for transmission. There were many rebuttals to Brown's claims in the newspapers and letters to the board, with people pointing out he was showing no scientific evidence that AC was more dangerous than DC. Westinghouse pointed out in letters to various newspapers the number of fires caused by DC equipment and suggested that Brown was obviously being controlled by Edison, something Brown continually denied.

A July edition of The Electrical Journal covered Brown's appearance before the New York Board of Electrical Control and the debate in technical societies over the merits of DC and AC, noting that:[35][50]

The battle of the currents is being fought this week in New York.

At a July meeting Board of Electrical Control, Brown's criticisms of AC and even his knowledge of electricity was challenged by other electrical engineers, some of whom worked for Westinghouse. At this meeting, supporters of AC provided anecdotal stories from electricians on how they had survived shocks from AC at voltages up to 1000 volts and argued that DC was the more dangerous of the two.[51]

Brown's demonstrations

Brown, determined to prove alternating current was more dangerous than direct current, at some point contacted Thomas Edison to see if he could make use of equipment to conduct experiments. Edison immediately offered to assist Brown in his crusade against AC companies. Before long, Brown was loaned space and equipment at Edison's West Orange, New Jersey laboratory, as well as laboratory assistant Arthur Kennelly.

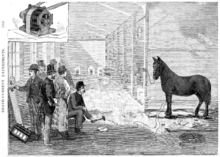

Brown paid local children to collect stray dogs off the street for his experiments with direct and alternating current.[52] After much experimentation killing a series of dogs, Brown held a public demonstration on July 30 in a lecture room at Columbia College.[53] With many participants shouting for the demonstration to stop and others walking out, Brown subjected a caged dog to several shocks with increasing levels of direct current up to 1,000 volts, which the dog survived. Brown then applied 330 volts of alternating current which killed the dog. Four days later he held a second demonstration to answer critics' claims that the DC probably weakened the dog before it died. In this second demonstration, three dogs were killed in quick succession with 300 volts of AC.[54] Brown wrote to a colleague that he was sure this demonstration would get the New York Board of Electrical Control to limit AC installations to 300 volts. Brown's campaign to restrict AC to 300 volts was unsuccessful but legislation did come close to passing in Ohio and Virginia.[55]

Collusion with Edison

What brought Brown to the forefront of the debate over AC and his motives remain unclear,[48] but historians note there grew to be some form of collusion between the Edison company and Brown.[48][56] Edison records seem to show it was Edison Electric Light treasurer Francis S. Hastings who came up with the idea of using Brown and several New York physicians to attack Westinghouse and the other AC companies in retaliation for what Hastings thought were unscrupulous bids by Westinghouse for lighting contracts in Denver and Minneapolis.[55] Hasting brought Brown and Edison together[57] and was in continual contact with Brown.[55] Edison Electric seemed to be footing the bill for some of Brown's publications on the dangers of AC.[58] In addition, Thomas Edison himself sent a letter to the city government of Scranton, Pennsylvania recommending Brown as an expert on the dangers of AC.[54] Some of this collusion was exposed in letters stolen from Brown's office and published in August 1889.

Patents and mergers

During this period Westinghouse continued to pour money and engineering resources into the goal of building a completely integrated AC system. To gain control of the Sawyer-Man lamp patents he bought Consolidated Electric Light in 1887. He bought the Waterhouse Electric Light Company in 1888 and the United States Illuminating Company in 1890, giving Westinghouse their own arc lighting systems as well as control over all the major incandescent lamp patents not controlled by Edison.[59] In April 1888 Westinghouse engineer Oliver B. Shallenberger developed an induction meter that used a rotating magnetic field for measuring alternating current, giving the company a way to calculate how much electricity a customer used.[60] In July 1888 Westinghouse paid a substantial amount to license Nikola Tesla's US patents for a poly-phase AC induction motor[61] and obtained a patent option on Galileo Ferraris' induction motor design.[62] Although the acquisition of a feasible AC motor gave Westinghouse a key patent in building a completely integrated AC system, the general shortage of cash the company was going through by 1890 meant development had to be put on hold for a while.[63] The difficulties of obtaining funding for such a capital intensive business was becoming a serious problem for the company and 1890 saw the first of several attempts by investor J. P. Morgan to take over Westinghouse Electric.[64][65]

Thomson-Houston was continuing to expand, buying seven smaller electric companies including a purchase of the Brush Electric Company in 1889.[66] By 1890 Thomson-Houston controlled the majority of the arc lighting systems in the US and a collection of its own US AC patents. Several of the business deals between Thomson-Houston and Westinghouse fell apart and in April 1888 a judge rolled back part of Westinghouse's original Gaulard Gibbs patent, stating it only covered transformers linked in series.[66]

With the help of the financier Henry Villard the Edison group of companies also went through a series of mergers: Edison Lamp Company, a lamp manufacturer in East Newark, New Jersey; Edison Machine Works, a manufacturer of dynamos and large electric motors in Schenectady, New York; Bergmann & Company, a manufacturer of electric lighting fixtures, sockets, and other electric lighting devices; and Edison Electric Light Company, the patent-holding company and the financial arm backed by J.P. Morgan and the Vanderbilt family for Edison's lighting experiments, merged.[67] The new company, Edison General Electric Company, was formed in January 1889 with the help of Drexel, Morgan & Co. and Grosvenor Lowrey with Villard as president.[68][69] It later included the Sprague Electric Railway & Motor Company.

The peak of the war

Through the fall of 1888 a battle of words with Brown specifically attacking Westinghouse continued to escalate. In November George Westinghouse challenged Brown's assertion in the pages of the Electrical Engineer that the Westinghouse AC systems had caused 30 deaths. The magazine investigated the claim and found at most only two of the deaths could be attributed to Westinghouse installations.[70]

Associating AC and Westinghouse with the electric chair

Although New York had a criminal procedure code that specified electrocution via an electric chair, it did not spell out the type of electricity, the amount of current, or its method of supply, since these were still relative unknowns.[71] The New York Medico-Legal Society, an informal society composed of doctors and lawyers, was given the task of working out the details and in late 1888 through early 1889 conducted a series of animal experiments on voltage amounts, electrode design and placement, and skin conductivity. During this time they sought the advice of Harold Brown as a consultant. This ended up expanding the war of currents into the development of the chair and the general debate over capital punishment in the US.[43]

After the Medico-Legal Society formed their committee in September 1888 chairman Frederick Peterson, who had been an assistant at Brown's July 1888 public electrocution of dogs with AC at Columbia College,[72] had the results of those experiments submitted to the committee. The claims that AC was more deadly than DC and was the best current to use was questioned, with some committee members pointing out that Brown's experiments were not scientifically carried out and were on animals smaller than a human being. At their November meeting the committee recommended 3,000 volts although the type of electricity, direct current or alternating current, was not determined.[72]

In order to more conclusively prove to the committee that AC was more deadly than DC, Brown contacted Edison Electric Light treasurer Francis S. Hastings to arrange the use of the West Orange laboratory.[43] There on December 5, 1888 Brown set up an experiment with members of the press, members of the Medico-Legal Society, the chairman of the death penalty commission, and Thomas Edison looking on. Brown used alternating current for all of his tests on animals larger than a human, including 4 calves and a lame horse, all dispatched with 750 volts of AC.[73] Based on these results the Medico-Legal Society's December meeting recommended the use of 1,000–1,500 volts of alternating current for executions and newspapers noted the AC used was half the voltage used in the power lines over the streets of American cities.

Westinghouse criticized these tests as a skewed self-serving demonstration designed to be a direct attack on alternating current.[74] On December 13 in a letter to the New York Times, Westinghouse spelled out where Brown's experiments were wrong and claimed again that Brown was being employed by the Edison company. Brown's December 18 letter refuted the claims and Brown even challenged Westinghouse to an electrical duel, with Brown agreeing to be shocked by ever-increasing amounts of DC power if Westinghouse submitted himself to the same amount of increasing AC power, first to quit loses.[74] Westinghouse declined the offer.

In March 1889 when members of the Medico-Legal Society embarked on another series of tests to work out the details of electrode composition and placement they turned to Brown for technical assistance.[43][75] Edison treasurer Hastings tried unsuccessfully to obtain a Westinghouse AC generator for the test.[43] They ended up using Edison's West Orange laboratory for the animal tests.

Also in March, Superintendent of Prisons Austin Lathrop asked Brown if he could supply the equipment needed for the executions as well as design the electric chair. Brown turned down the job of designing the chair but did agree to fulfill the contract to supply the necessary electrical equipment.[43] The state refused to pay up front, and Brown apparently turned to Edison Electric as well as Thomson-Houston Electric Company to help obtaining the equipment. This became another behind-the-scenes maneuver to acquire Westinghouse AC generators to supply the current, apparently with the help of the Edison company and Westinghouse's chief AC rival, Thomson-Houston.[43][76] Thomson-Houston arranged to acquire three Westinghouse AC generators by replacing them with new Thomson-Houston AC generators. Thomson-Houston president Charles Coffin had at least two reasons for obtaining the Westinghouse generators; he did not want his company's equipment to be associated with the death penalty and he wanted to use one to prove a point, paying Brown to set up a public efficiency test to show that Westinghouse's sales claim of manufacturing 50% more efficient generators was false.[77]

That spring Brown published "The Comparative Danger to Life of the Alternating and Continuous Electrical Current" detailing the animal experiments done at Edison's lab and claiming they showed AC was far deadlier than DC.[78] This 61-page professionally printed booklet (possibly paid for by the Edison company) was sent to government officials, newspapers, and businessmen in towns with populations greater than 5,000 inhabitants.[58]

In May 1889 when New York had its first criminal sentenced to be executed in the electric chair, a street merchant named William Kemmler, there was a great deal of discussion in the editorial column of the New York Times as to what to call the then-new form of execution. The term "Westinghoused" was put forward as well as "Gerrycide" (after death penalty commission head Elbridge Gerry), and "Browned".[79] The Times hated the word that was eventually adopted, electrocution, describing it as being pushed forward by "pretentious ignoramuses".[80] One of Edison's lawyers wrote to his colleague expressing an opinion that Edison's preference for dynamort, ampermort and electromort were not good terms but thought Westinghoused was the best choice.[79]

The Kemmler appeal

William Kemmler was sentenced to die in the electric chair around June 24, 1889, but before the sentence could be carried out an appeal was filed on the grounds that it constituted cruel and unusual punishment under the U.S. Constitution. It became obvious to the press and everyone involved that the politically connected (and expensive) lawyer who filed the appeal, William Bourke Cockran, had no connection to the case but did have connection to the Westinghouse company, obviously paying for his services.[81]

During fact-finding hearings held around the state beginning on July 9 in New York City, Cockran used his considerable skills as a cross-examiner and orator to attack Brown, Edison, and their supporters. His strategy was to show that Brown had falsified his test on the killing power of AC and to prove that electricity would not cause certain death and simply lead to torturing the condemned. In cross examination he questioned Brown's lack of credentials in the electrical field and brought up possible collusion between Brown and Edison, which Brown again denied. Many witnesses were called by both sides to give firsthand anecdotal accounts about encounters with electricity and evidence was given by medical professionals on the human body's nervous system and the electrical conductivity of skin. Brown was accused of fudging his tests on animals, hiding the fact that he was using lower current DC and high-current AC.[82] When the hearing convened for a day at Edison's West Orange lab to witness demonstrations of skin resistance to electricity, Brown almost got in a fight with a Westinghouse representative, accusing him of being in the Edison laboratory to conduct industrial espionage.[83] Newspapers noted the often contradictory testimony was raising public doubts about the electrocution law but after Edison took the stand many accepted assurances from the "wizard of Menlo Park" that 1,000 volts of AC would easily kill any man.[84]

After the gathered testimony was submitted and the two sides presented their case, Judge Edwin Day ruled against Kemmler's appeal on October 9 and US Supreme Court denied Kemmler's appeal on May 23, 1890.[85]

When the chair was first used, on August 6, 1890, the technicians on hand misjudged the voltage needed to kill William Kemmler. After the first jolt of electricity Kemmler was found to be still breathing. The procedure had to be repeated and a reporter on hand described it as "an awful spectacle, far worse than hanging." George Westinghouse commented: "They would have done better using an axe."[86]

Brown's collusion exposed

On August 25, 1889 the New York Sun ran a story headlined:

"For Shame, Brown! – Disgraceful Facts About the Electric Killing Scheme; Queer Work for a State's Expert; Paid by One Electric Company to Injure Another"

The story was based on 45 letters stolen from Brown's office that spelled out Brown's collusion with Thomson-Houston and Edison Electric. The majority of the letters were correspondence between Brown and Thomson-Houston on the topic of acquiring the three Westinghouse generators for the state of New York as well as using one of them in an efficiency test. They also showed that Brown had received $5,000 from Edison Electric to purchase the surplus Westinghouse generators from Thomson-Houston. Further Edison involvement was contained in letters from Edison treasurer Hastings asking Brown to send anti-AC pamphlets to all the legislators in the state of Missouri (at the company's expense), Brown requesting that a letter of recommendation from Thomas Edison be sent to Scranton, Pennsylvania, as well as Edison and Arthur Kennelly coaching Brown in his upcoming testimony in the Kemmler appeal trial.[76][87][88]

Brown was not slowed down by this revelation and characterized his efforts to expose Westinghouse as the same as going after a grocer who sells poison and calls it sugar.[76][87][88]

The "Electric Wire Panic"

1889 saw another round of deaths attributed to alternating current including a lineman in Buffalo, New York, four linemen in New York City, and a New York fruit merchant who was killed when the display he was using came in contact with an overhead line. NYC Mayor Hugh J. Grant, in a meeting with the Board of Electrical Control and the AC electric companies, rejected the claims that the AC lines were perfectly safe saying "we get news of all who touch them through the coroners office".[25] On October 11, 1889, John Feeks, a Western Union lineman, was high up in the tangle of overhead electrical wires working on what were supposed to be low-voltage telegraph lines in a busy Manhattan district. As the lunchtime crowd below looked on he grabbed a nearby line that, unknown to him, had been shorted many blocks away with a high-voltage AC line. The jolt entered through his bare right hand and exited his left steel studded climbing boot. Feeks was killed almost instantly, his body falling into the tangle of wire, sparking, burning, and smoldering for the better part of an hour while a horrified crowd of thousands gathered below. The source of the power that killed Feeks was not determined although United States Illuminating Company lines ran nearby.[89]

Feeks' public death sparked a new round of people fearing the electric lines over their heads in what has been called the "Electric Wire Panic".[90] The blame seemed to settle on Westinghouse since, Westinghouse having bought many of the lighting companies involved, people assumed Feeks' death was the fault of a Westinghouse subsidiary.[90] Newspapers joined into the public outcry following Feeks' death, pointing out men's lives "were cheaper to this monopoly than insulated wires" and calling for the executives of AC companies to be charged with manslaughter. The October 13, 1889, New Orleans Times-Picayune noted "Death does not stop at the door, but comes right into the house, and perhaps as you are closing a door or turning on the gas you are killed."[91] Harold Brown's reputation was rehabilitated almost overnight with newspapers and magazines seeking his opinion and reporters following him around New York City where he measured how much current was leaking from AC power lines.[92]

At the peak of the war of currents, Edison himself joined the public debate for the first time, denounced AC current in a November 1889 article in the North American Review titled "The Dangers of Electric Lighting". Edison put forward the view that burying the high-voltage lines was not a solution, and would simply move the deaths underground and be a "constant menace" that could short with other lines threatening people's homes and lives.[89][93] He stated the only way to make AC safe was to limit its voltage and vowed Edison Electric would never adopt AC as long as he was in charge.[89]

George Westinghouse was characterized as a villain trying to defend pole-mounted AC installations that he knew were unsafe, and fumbled his replies to the questions put to him by reporters, attempting to point out all the other things in a large city that were more dangerous than AC.[90][89] However, his subsequent response, printed in the North American Review, was much improved, highlighting that his AC/transformer system actually used lower household voltages than the Edison DC system. He also pointed out 87 deaths in one year caused by street cars and gas lighting, versus only 5 accidental electrocutions and no in-home deaths attributed to AC current.[89]

The crowd that watched Feeks contained many New York aldermen due to the site of the accident being near the New York government offices and the horrifying affair galvanized them into the action of passing the law on moving utilities underground.[94] The electric companies involved obtained an injunction preventing their lines from being cut down immediately but shut down most of their lighting until the situation was settled, plunging many New York streets into darkness.[66] The legislation ordering the cutting down of all of the utility lines was finally upheld by the New York Supreme Court[which?] in December. The AC lines were cut down, keeping many New York City streets in darkness for the rest of the winter, since little had been done by the overpaid Tammany Hall city supervisors who were supposed arrange the building of the underground "subways" to house them.[93]

The current war ends

Even with the Westinghouse propaganda losses, the war of currents itself was winding down with direct current on the losing side. This was due in part to Thomas Edison himself leaving the electric power business.[95] Edison was becoming marginalized in his own company, having lost majority control in the 1889 merger that formed Edison General Electric.[96] In 1890, he told president Henry Villard he thought it was time to retire from the lighting business and moved on to an iron ore refining project that preoccupied his time.[3] Edison's dogmatic anti-AC values were no longer controlling the company. By 1889, Edison's Electric's own subsidiaries were lobbying to add AC power transmission to their systems, and in October 1890, Edison Machine Works began developing AC-based equipment.

With Thomas Edison no longer involved with Edison General Electric, the war of currents came to a close with a financial merger.[97] Edison president Henry Villard, who had engineered the merger that formed Edison General Electric, was continually working on the idea of merging that company with Thomson-Houston or Westinghouse. He saw a real opportunity in 1891. The market was in a general downturn causing cash shortages for all the companies concerned and Villard was in talks with Thomson-Houston, which was now Edison General Electric's biggest competitor. Thomson-Houston had a habit of saving money on development by buying, or sometimes stealing, patents. Patent conflicts were stymieing the growth of both companies and the idea of saving on some 60 ongoing lawsuits as well as saving on profit losses of trying to undercut each other by selling generating plants below cost pushed forward the idea of this merger in financial circles.[3][96] Edison hated the idea and tried to hold it off, but Villard thought his company, now winning its incandescent light patent lawsuits in the courts, was in a position to dictate the terms of any merger.[3] As a committee of financiers, which included J.P. Morgan, worked on the deal in early 1892, things went against Villard. In Morgan's view, Thomson-Houston looked on the books to be the stronger of the two companies and engineered a behind the scenes deal announced on April 15, 1892, that put the management of Thomson-Houston in control of the new company, now called General Electric (dropping Edison's name). Thomas Edison was not aware of the deal until the day before it happened.

The fifteen electric companies that existed five years before had merged down to two: General Electric and Westinghouse. The war of currents came to an end, and this merger of the Edison company, along with its lighting patents, and the Thomson-Houston, with its AC patents, created a company that controlled three quarters of the US electrical business.[2][3] From this point on, General Electric and Westinghouse were both marketing alternating current systems.[98] Edison put on a brave face, noting to the media how his stock had gained value in the deal, but privately he was bitter that his company and all of his patents had been turned over to the competition.[2]

Aftermath

Even though the institutional war of currents had ended in a financial merger, the technical difference between direct and alternating current systems followed a much longer technical merger.[97] Due to innovation in the US and Europe, alternating current's economy of scale with very large generating plants linked to loads via long-distance transmission was slowly being combined with the ability to link it up with all of the existing systems that needed to be supplied. These included single phase AC systems, poly-phase AC systems, low-voltage incandescent lighting, high voltage arc lighting, and existing DC motors in factories and street cars. In the engineered universal system these technological differences were temporarily being bridged via the development of rotary converters and motor–generators that allowed the large number of legacy systems to be connected to the AC grid.[98][97] These stopgaps were slowly replaced as older systems were retired or upgraded.

In May 1892, Westinghouse Electric managed to underbid General Electric on the contract to electrify the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and, although they made no profit, their demonstration of a safe, effective and highly flexible universal alternating current system powering all of the disparate electrical systems at the Exposition led to them winning the bid at the end of that year to build an AC power station at Niagara Falls. General Electric was awarded contracts to build AC transmission lines and transformers in that project and further bids at Niagara were split with GE who were quickly catching up in the AC field[2] due partly to Charles Proteus Steinmetz, a Prussian mathematician who was the first person to fully understand AC power from a solid mathematical standpoint. General Electric hired many talented new engineers to improve its design of transformers, generators, motors and other apparatus.[99]

A three-phase three-wire transmission system had already been deployed in Europe at the International Electro-Technical Exhibition of 1891, where Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky used this system to transmit electric power over a distance of 176 km with 75% efficiency. In 1891 he also created a three-phase transformer, the short-circuited (squirrel-cage) induction motor and designed the world's first three-phase hydroelectric power plant.

Patent lawsuits were still hampering both companies and bleeding off cash, so in 1896, J. P. Morgan engineered a patent sharing agreement between the two companies that remained in force for 11 years.[100]

In 1897 Edison sold his remaining stock in Edison Electric Illuminating of New York to finance his iron ore refining prototype plant.[101] In 1908, Edison said to George Stanley, son of AC transformer inventor William Stanley, Jr., "Tell your father I was wrong", likely an admission that he had underestimated the developmental potential of alternating current.[102]

Remnant and existent DC systems

Some cities continued to use DC well into the 20th century. For example, central Helsinki had a DC network until the late 1940s, and Stockholm lost its dwindling DC network as late as the 1970s. A mercury-arc valve rectifier station could convert AC to DC where networks were still used. Parts of Boston, Massachusetts, along Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue still used 110 volts DC in the 1960s, causing the destruction of many small appliances (typically hair dryers and phonographs) used by Boston University students, who ignored warnings about the electricity supply.

New York City's electric utility company, Consolidated Edison, continued to supply direct current to customers who had adopted it early in the twentieth century, mainly for elevators. The New Yorker Hotel, constructed in 1929, had a large direct-current power plant and did not convert fully to alternating-current service until well into the 1960s.[103] This was the building in which AC pioneer Nikola Tesla spent his last years, and where he died in 1943. New York City's Broadway theaters continued to use DC services until 1975, requiring the use of outmoded manual resistance dimmer boards operated by several stagehands. This practice ended when the musical A Chorus Line introduced computerized lighting control and thyristor (SCR) dimmers to Broadway, and New York theaters were finally converted to AC.[104]

In January 1998, Consolidated Edison started to eliminate DC service. At that time there were 4,600 DC customers. By 2006, there were only 60 customers using DC service, and on November 14, 2007, the last direct-current distribution by Con Edison was shut down. Customers still using DC were provided with on-site AC to DC rectifiers.[105] In 2012, Pacific Gas and Electric Company still provided DC power to some locations in San Francisco, primarily for elevators, supplied by close to 200 rectifiers each providing power for 7–10 customers.[106]

The Central Electricity Generating Board in the UK maintained a 200–volt DC generating station at Bankside Power Station in London until 1981. It exclusively powered DC printing machinery in Fleet Street, then the heart of the UK's newspaper industry. It was decommissioned later in 1981 when the newspaper industry moved into the developing docklands area further down the river (using modern AC-powered equipment).

High-voltage direct current (HVDC) systems are used for bulk transmission of energy from distant generating stations, for underwater lines, and for interconnection of separate alternating-current systems.

See also

- Format war

- History of electric power transmission

- History of electronic engineering

- Timeline of electrical and electronic engineering

- Topsy (elephant) – in popular culture associated with the war of currents

References

- Citations

- ^ a b Skrabec (2012), p. 86.

- ^ a b c d Essig (2009), p. 268.

- ^ a b c d e Bradley (2011), pp. 28–29.

- ^ "Off Goes the Power Current Started by Thomas Edison". 14 November 2007.

- ^ "Charles Francis Brush". Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ Jonnes (2003), p. 47.

- ^ "Charles Francis Brush". Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ^ "Brush Arc Lamps". Electric Museum.com.

- ^ "Arc Lamps – How They Work & History". Edison Tech Center. 2015.

- ^ a b Bradley (2011).

- ^ Rockman (2004), p. 131.

- ^ McNichol (2006), p. 80.

- ^ Moran (2007), p. 42.

- ^ McNichol (2006), p. 81.

- ^ "Notes on the Jablochkoff System of Electric Lighting". Journal of the Society of Telegraph Engineers. IX (32). Society of Telegraph Engineers: 143. March 24, 1880. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ Carlson, W. Bernard (2013). Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-69116-561-5.

- ^ M. Whelan, Steve Rockwell, Steve Normandin, The History of the Transformer, Edison Tech Center, edisontechcenter.org

- ^ M. Whelan, Steve Rockwell, Steve Normandin, The History of the Transformer, Edison Tech Center, edisontechcenter.org

- ^ Great Barrington Historical Society, Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

- ^ "The Great Barrington Electrification, 1886". Edison Tech Center. 2014.

- ^ Skrabec (2007), p. 97.

- ^ Davis, L. J. (2012). Fleet Fire: Thomas Edison and the Pioneers of the Electric Revolution. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61145-659-2.

- ^ Higonnet, Landes & Rosovsky (1991), p. 89.

- ^ a b Essig (2009), p. 137.

- ^ a b c d Klein (2010), p. 263.

- ^ Essig (2009), p. 139.

- ^ Stross (2007), p. 171.

- ^ Jonnes (2003), pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b c Jonnes (2003), pp. 146. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEJonnes2003146" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Moran (2007), p. 60.

- ^ Klein (2010), p. 257.

- ^ Stross (2007), p. 174.

- ^ Carlson, W. Bernard (1993). "Competition and Consolidation in the Electrical Manufacturing Industry, 1889–1892" (PDF). Technological Competitiveness: Contemporary and Historical Perspectives on Electrical, Electronics, and Computer Industries. Piscataway, New Jersey: IEEE Press. pp. 287–311.

- ^ Stross (2007), pp. 171–174.

- ^ a b Essig (2009), p. 135.

- ^ Stross (2007), pp. 171–173.

- ^ Brandon (1999), pp. 12–14.

- ^ Brandon (1999), p. 21.

- ^ Brandon (1999), p. 24.

- ^ "Southwick, Alfred Porter". American National Biography Online.

- ^ Brandon (1999), pp. 54 & 57–58.

- ^ Jonnes (2003), p. 420.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reynolds, Terry S.; Bernstein, Theodore (March 1989). "Edison and "The Chair"" (PDF). Technology and Society. Vol. 8, no. 1. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

- ^ "Thomas Alva Edison". Scientific American. 87 (26): 463. December 27, 1902. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican12271902-463.

- ^ Stross (2007), pp. 172.

- ^ a b Jonnes (2003), p. 143.

- ^ Essig (2009), pp. 139–140.

- ^ a b c Jonnes (2003), p. 166.

- ^ Jonnes (2003), p. 167.

- ^ The Electrical Journal, Volume 21, July 21, 1888, p.415.

- ^ Essig (2009), p. 141.

- ^ Jonnes (2003), p. 173.

- ^ Rockman (2004), p. 469.

- ^ a b Jonnes (2003), p. 174.

- ^ a b c Carlson, W. Bernard (2003). Innovation as a Social Process: Elihu Thomson and the Rise of General Electric. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-52153-312-6.

- ^ Brandon (1999), pp. 70 & 261.

- ^ Klein (2010), Chapter 13.

- ^ a b Essig (2009), p. 157.

- ^ Klein (2010), p. 281.

- ^ Seifer, Marc (1 May 1998). Wizard: The Life And Times of Nikola Tesla. Citadel. ISBN 978-0-8065-3556-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ Klooster, John W. (1 January 2009). Icons of Invention: The Makers of the Modern World from Gutenberg to Gates. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-34743-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jonnes (2003).

- ^ Skrabec (2007), p. 127.

- ^ Skrabec (2007), pp. 128–130.

- ^ Skrabec, Quentin R. (2010). The World's Richest Neighborhood: How Pittsburgh's East Enders Forged American Industry. New York: Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-795-3.

- ^ a b c Klein (2010), p. 292.

- ^ "Electricity". A Brief History of Con Edison. Con Edison. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Wredge, Charles D.; Greenwood, Ronald G. (1984). "William E. Sawyer and the Rise and Fall of America's First Incandescent Electric Light Company, 1878–1881" (PDF). Business and Economic History. 2 (13). Business History Conference: 31–48. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- ^ Israel, Paul (1998). Edison: A Life of Invention. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 173–174, 178. ISBN 0-471-52942-7.

- ^ Moran (2007), p. 118.

- ^ Moran (2007), pp. 102–104.

- ^ a b Moran (2007), p. 102.

- ^ Essig (2009), pp. 152–155.

- ^ a b Brandon (1999), p. 82.

- ^ Essig (2009), p. 225.

- ^ a b c Essig (2009), pp. 190–195.

- ^ Essig (2009), pp. 193.

- ^ Moran (2007), p. 106.

- ^ a b Moran (2007), pp. xxi–xxii.

- ^ Moran (2007), p. xxii.

- ^ Brandon (1999), p. 101.

- ^ Brandon (1999), p. 119.

- ^ Brandon (1999), p. 115.

- ^ Brandon (1999), p. 125.

- ^ McNichol (2006), p. 120.

- ^ McNichol (2006), p. 125.

- ^ a b Penrose, James F. (1994). "Inventing Electrocution". American Heritage of Invention & Technology. 9 (4): 34–44. PMID 11613165. Archived from the original on February 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Jonnes (2003), pp. 191–198.

- ^ a b c d e Stross (2007), p. 179.

- ^ a b c Klein (2010).

- ^ Essig (2009), pp. 217.

- ^ Essig (2009), p. 218.

- ^ a b Jonnes (2003), p. 200.

- ^ Stross (2007), p. 178.

- ^ Hughes (1993), pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b Sloat, Warren (1979). 1929: America Before the Crash. New York: Macmillan. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-02611-800-2.

- ^ a b c Hughes (1993), pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b Garud, Raghu; Kumaraswamy, Arun; Langlois, Richard (2009). Managing in the Modular Age: Architectures, Networks, and Organizations. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-40514-194-9.

- ^ The General Electric Story, The Hall of History.

- ^ Skrabec (2007), p. 190.

- ^ Freeberg, Ernest (2013). The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America. New York: The Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-426-5.

- ^ Higonnet, Landes & Rosovsky (1991), p. 113.

- ^ Blalock, Tom (23 January 2006). "Powering the New Yorker: A Hotel's Unique Direct Current System". Power and Energy. Vol. 4, no. 1. IEEE. pp. 70–76. doi:10.1109/MPAE.2006.1578536.

- ^ Blalock, Tom (October 2002). "History and reflections on the way things were: Edison's Direct Current Influenced "Broadway" Show Lighting". Power and Engineering Review. Vol. 22, no. 10. IEEE. ISSN 0272-1724.

- ^ Lee, Jennifer (November 16, 2007). "Off Goes the Power Current Started by Thomas Edison". The New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- ^ Fairley, Peter (15 November 2012). "San Francisco's Secret DC Grid". IEEE Spectrum.

- Bibliography

- Bradley, Robert L. Jr. (2011). Edison to Enron: Energy Markets and Political Strategies. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-47091-736-7.

- Brandon, Craig (1999). The Electric Chair: An Unnatural American History. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-58538-476-4.

- Essig, Mark (2009). Edison and the Electric Chair: A Story of Light and Death. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-0-80271-928-7.

- Higonnet, Patrice L. R.; Landes, David S.; Rosovsky, Henry (1991). Favorites of Fortune: Technology, Growth, and Economic Development Since the Industrial Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67429-520-9.

- Hughes, Thomas Parke (1993). Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-80182-873-7.

- Jonnes, Jill (2003). Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-37550-739-7.

- Klein, Maury (2010). The Power Makers: Steam, Electricity, and the Men Who Invented Modern America. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-59691-834-4.

- McNichol, Tom (2006). AC/DC: The Savage Tale of the First Standards War. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7879-8267-6.

- Moran, Richard (2007). Executioner's Current: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and the Invention of the Electric Chair. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-37572-446-6.

- Rockman, Howard B. (2004). Intellectual Property Law for Engineers and Scientists. Wiley-IEEE Press. ISBN 978-0-471-44998-0.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007). George Westinghouse: Gentle Genius. New York: Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-404-4.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2012). The 100 Most Significant Events in American Business: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-31339-863-6.

- Stross, Randall E. (2007). The Wizard of Menlo Park: How Thomas Alva Edison Invented the Modern World. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-1-40004-762-8.

Further reading

- Berton, Pierre (1997). Niagara: A History of the Falls. New York: Kodansha International. ISBN 978-1-56836-154-3.

- Bordeau, Sanford P. (1982). Volts to Hertz—the rise of electricity: from the compass to the radio through the works of sixteen great men of science whose names are used in measuring electricity and magnetism. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Burgess Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-80874-908-0.

- Edquist, Charles; Hommen, Leif; Tsipouri, Lena J. (2000). Public technology procurement and innovation. Economics of science, technology, and innovation. Vol. 16. Boston: Kluwer Academic. ISBN 978-0-79238-685-8.

- "A new system of alternating current motors and transformers". The Electrical Engineer. London, UK: Biggs & Co.: 568–572 May 18, 1888.

- "Practical electrical problems at Chicago". The Electrical Engineer. London, UK: Biggs & Co.: 458–459, 484–485 & 489–490 May 12, 1893.

- Foster, Abram John (1979). The Coming of the Electrical Age to the United States. New York: Arno Press. ISBN 978-0-40511-983-5.

External links

- "Thomas Edison Hates Cats". Pinky Show. January 17, 2007. (AC vs DC an online video mini-history).

- "War of the Currents". PBS.

- Chang, Maria. "War of the Currents". University of California at Berkeley. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011.

- 1880s in science

- 1880s in technology

- 1880s in the United States

- 1890s in science

- 1890s in technology

- 1890s in the United States

- Animal rights

- Business rivalries

- Cruelty to animals

- Electric power

- Electric power transmission systems in the United States

- Electrical safety

- Energy development

- History of electrical engineering

- Ideological rivalry

- Nikola Tesla

- Thomas Edison

- Scientific rivalry