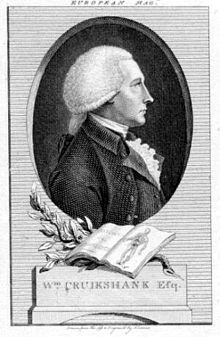

William Cruickshank | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | circa 1740 |

| Died | circa 1811 |

| Citizenship | Scottish |

| Alma mater | Royal College of Surgeons of England King's College, Aberdeen |

| Known for | characterization of carbon monoxide |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | Royal Military Academy, Woolwich |

William Cruickshank (born circa 1740 or 1750,[1] died 1810 or 1811[2]) was a Scottish military surgeon and chemist, and professor of chemistry at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich.[3]

William Cruickshank was awarded a diploma by the Royal College of Surgeons of England on 5 October 1780. In March 1788 he became assistant to Adair Crawford at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, at a salary of £30 a year. On 24 June 1802, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS).[4]

Discoveries and inventions

In 1797 he discovered that concentrated urine treated with nitric acid gives crystals, which exhibit acidic properties in solution, and may detonate if set on fire. That was urea nitrate.[5][6]

He identified carbon monoxide as a compound containing carbon and oxygen in 1800.[7] In 1800 he also used chlorine to purify water.[8] He also discovered the chloralkali process.[9]

Strontium

Some authors credit Cruickshank with first suspecting an unknown substance in a Scottish mineral, strontianite, found near Strontian, in Argyleshire. Other authors name Adair Crawford for the discovery of this new earth, due to the mineral's property of imparting a redding color to a flame.[10] It was later isolated by Humphry Davy and is now known as strontium.[11][12]

Diabetes

Cruickshank worked with John Rollo at Woolwich in the 1790s, and some of his discoveries about diabetes were published in Rollo's book on the dietary treatment of the condition.[4] This research led him to isolate urea in 1798, though his priority was not recognised at the time.[13]

Trough battery

Circa 1800, Cruickshank invented the Trough battery, an improvement on Alessandro Volta's voltaic pile. The plates were arranged horizontally in a trough, rather than vertically in a column.[14]

Electrolysis

Shortly after learning of Alessandro Volta's discovery of the Voltaic Pile in 1800, Cruickshank conducted a number of experiments involving electrolysis. He connected wires of silver to the poles of a battery and placed them into a solution of distilled water, and later into a variety of other solutions, observing the results. When the wires were placed into the various solutions of lead acetate, copper sulfate and silver nitrate, deposits of pure lead, copper and silver formed, respectively, on one wire. From these experiments he observed that "where metallic solutions are employed instead of water, the same wire which separates the hydrogen revives the metallic calx, and deposits it at the extremity of the wire in its pure metallic state."[15] This process of extraction of pure metals from metallic solutions is known today as electrowinning. It is used in the refining of copper and other metals.

Retirement and death

In March 1803, Cruickshank became very ill and it is possible that this was due to exposure to phosgene during his experiments. On 6 July 1804, he retired on a pension of 10 shillings a day. He died in 1810 or 1811 and military records state that the death occurred in Scotland.[4]

See also

References

- ^ Watson, K. D. (23 September 2004). "Cruickshank, William (d. 1810/11), military surgeon and chemist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/57592. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Neild, G. H. (September 1996). "William Cruickshank (FRS-1802): clinical chemist". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 11 (9): 1885–1889. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027695. ISSN 0931-0509. PMID 8918649.

- ^ Coutts, A. (June 1959). "William Cruickshank of Woolwich". Annals of Science. 15 (2): 121–133. doi:10.1080/00033795900200118. ISSN 0003-3790.

- ^ a b c Watson, K. D. "Cruickshank, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 14 (online ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 519–20. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/57592. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Rosenfeld, Louis (1999). Four Centuries of Clinical Chemistry. CRC Press. ISBN 978-90-5699-645-1.

- ^ Rollo, John; Cruickshank, William (1798). Cases of the diabetes mellitus : with the results of the trials of certain acids, and other substances, in the cure of the lues venerea. Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine. London : Printed by T. Gillet, for C. Dilly, in the Poultry.

- ^ Hopper, Christopher P.; Zambrana, Paige N.; Goebel, Ulrich; Wollborn, Jakob (June 2021). "A brief history of carbon monoxide and its therapeutic origins". Nitric Oxide. 111–112: 45–63. doi:10.1016/j.niox.2021.04.001. PMID 33838343. S2CID 233205099.

- ^ Rideal, Samuel (1895). Disinfection and Disinfectants, p. 59. J.B. Lippincott Co.

- ^ "Chloralkali process", Wikipedia, 7 October 2020, retrieved 7 October 2020

- ^ A Handbook to a Collection of the Minerals of the British Islands... by Frederick William Rudler publ. HMSO (1905) page 211(available digitized by Google)

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements: X. The alkaline earth metals and magnesium and cadmium". Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (6): 1046–1057. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9.1046W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1046.

- ^ Partington, J.R. (1942). "The early history of strontium". Annals of Science. 5 (2): 157–166. doi:10.1080/00033794200201411.

- ^ Schiller, Joseph (1967). "Wöhler, l'urée et le vitalisme". Sudhoffs Archiv. 51 (3): 229–243. ISSN 0039-4564. JSTOR 20775601.

- ^ Electricity by Robert M Ferguson, publ. Chambers (1873) page 169 (available digitized by Google).

- ^ Elements of Galvanism in Theory and Practice, Vol. 2 by C.H. Wilkinson, publ. M'Millan (1804) pages 52 - 60 (available digitized by Google).