| Öljaitü Muhammad Khodabandeh | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pādishāh-i Īrānzamīn[1] (Padishah of the Land of Iran) | |||||

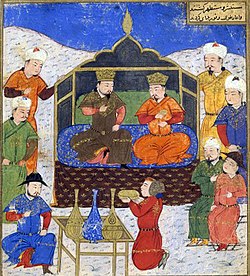

Öljaitü and ambassadors from the Yuan dynasty, 1438, "Majma' al-Tavarikh" | |||||

| Ilkhan | |||||

| Reign | 9 July 1304 – 16 December 1316 | ||||

| Coronation | 19 July 1304 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ghazan | ||||

| Successor | Abu Sa'id | ||||

| Viceroy of Khorasan | |||||

| Reign | 1296 – 1304 | ||||

| Predecessor | Nirun Aqa | ||||

| Successor | Abu Sa'id | ||||

| Born | 24 March 1282[2] | ||||

| Died | 16 December 1316 (aged 34) | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Issue | Bastam Tayghur Sulayman Shah Abu'l Khayr Abu Sa'id Ilchi (alleged) Dowlandi Khatun Sati Beg Sultan Khatun | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ilkhanate | ||||

| Father | Arghun | ||||

| Mother | Uruk Khatun | ||||

| Religion | Buddhism (until 1291) Christianity (until 1295) Sunni Islam (until 1310) Shia Islam (until his death)[3] | ||||

Öljaitü,[a] also known as Mohammad-e Khodabandeh[b] (24 March 1282 – 16 December 1316), was the eighth Ilkhanid dynasty ruler from 1304 to 1316 in Tabriz, Iran. His name 'Öjaitü' means 'blessed' in the Mongolian language and his last name 'Khodabandeh' means 'God's servant' in the Persian language.

He was the son of the Ilkhan ruler Arghun, brother and successor of Mahmud Ghazan (5th successor of Genghis Khan), and great-grandson of the Ilkhanate founder Hulagu.

Early life

Öljaitü was born to Arghun and his third wife, Keraite Christian Uruk Khatun on 24 March 1282 during his father's viceroyalty in Khorasan.[4] He was given the name Khar-banda (mule driver)[5] at birth, raised as Buddhist and later baptised in 1291,[6] receiving the name Nikolya (Nicholas) after Pope Nicholas IV.[7] However, according to Tarikh-i Uljaytu (History of Oljeitu), Öljeitu was at first known as "Öljei Buqa", and then "Temüder", and finally "Kharbanda".[1] Various c. Same source also mentions that it rained when he was born, and the delighted Mongols called him by the Mongolian name Öljeitu (Өлзийт), meaning auspicious. He was later converted to Sunni Islam along with his brother Ghazan. Like his brother, he changed his first name to the Islamic name Muhammad.

He participated in battles involving Ghazan's fight against Baydu. After his brother Ghazan's accession to throne, he was appointed as viceroy of Khorasan.[8] Despite being appointed heir of Ghazan since 1299,[9] after hearing news of his death he sought to eliminate potential rivals to throne. First such act was taken against Prince Alafrang, son of Gaykhatu. He was killed by an emissary of Öljaitü on 30 May 1304.[10] Another powerful emir, Horqudaq was likewise captured and executed.[11]

Reign

He arrived in the Ujan plain on 9 July 1304[12] and was crowned on 19 July 1304.[11] Rashid al-Din wrote that he adopted the name Oljeitu following Yuan emperor Öljeitu Temür enthroned in Dadu. His full regnal title was Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad Khudabanda Öljaitü Sultan. Upon accession, he made several appointments, such Qutluqshah to the post of commander-in-chief of Ilkhanate army, Rashid al-Din and Sa'd al-Din Savaji as his viziers on 22 July 1304. Another appointment was Asil al-Din, son of Nasir al-Din Tusi as his father's successor to head Maragheh observatory. Another political decision was revoking Kerman from Qutluqkhanid Qutb al-Din Shah Jahan on 21 April 1304. Öljaitü appointed his father-in-law and uncle Irinjin as viceroy of Anatolia on 27 June 1305.

He received ambassadors from the Yuan dynasty (19 September 1305), Chagatai Khanate (in persons of Chapar, son of Kaidu and Duwa, son of Baraq) and Golden Horde (8 December 1305) in the same year, establishing an intra-Mongol peace.[11] His reign also saw a wave of migration from Central Asia during 1306. Certain Borjigid princes, such as Mingqan Ke'un (grandson of Ariq Böke and grandfather of future Arpa Ke'un), Sarban (son of Kaidu), Temür (a descendant of Jochi Qasar) arrived in Khorasan with 30.000[13] or 50.000 followers.

He undertook an expedition to Herat against the Kartid ruler Fakhr al-Din in 1306, but succeeded only briefly; his emir Danishmend was killed during the ambush. He started his second military campaign in June 1307 towards Gilan. It was a success thanks to combines forces of emirs like Sutai, Esen Qutluq, Irinjin, Sevinch, Chupan, Toghan and Mu'min. Despite initial success, his commander-in-chief Qutluqshah was defeated and killed during the campaign, which paved way for Chupan to rise in ranks. Following this, he ordered another campaign against Kartids, this time commanded by the late emir Danishmend's son Bujai. Bujai was successful after a siege from 5 February to 24 June 1306, finally capturing the citadel. A corps of Frankish mangonel specialists is known to have accompanied the Ilkhanid army in this conquest.[14]

Another important event of 1307 was the completion of the Jami al-Tawarikh by Rashid al-Din on 14 April 1307.[15] Later in 1307, a revolt broke in Kurdistan under the leadership of certain Musa, who claimed to be the Mahdi. The uprising was swiftly defeated.[16] Another religious revolt, this time by 10.000 strong Christians, broke out in Irbil. Despite Mar Yahballaha's best efforts to avert the impending doom, the citadel was at last taken after a siege by Ilkhanate troops and Kurdish tribesmen on 1 July 1310, and all the defenders were massacred, including many of the Assyrian inhabitants of the lower town.[17]

An important change in administration happened in 1312 when Öljaitü's vizier Sa'd al-Din Savaji was arrested on charges of corruption and executed on 20 February 1312. He was soon replaced by Taj al-Din Ali Shah, who would head the Ilkhanate civil administration until 1323. Another victim of the purge was Taj al-Din Avaji, a follower of Sa'd al-Din. Öljaitü also finally launched a last campaign against the Mamluks, in which he was unsuccessful, though he reportedly briefly took Damascus.[18] It was when Mamluk emirs, former governor of Aleppo—Shams al-Din Qara Sonqur and governor of Tripoli—al-Afram defected to Öljaitü. Despite extradition requests from Egypt, ilkhan invested Qara Sonqur (now under the new name Aq Sonqur) with the governorate of Maragheh and al-Afram with Hamadan.[11] Qara Sonqur was later given Oljath—daughter of Abaqa Khan on 17 January 1314.[1]

Meanwhile, relations between other Mongol realms were getting heated. The new khan of Golden Horde, Ozbeg sent an emissary to Öljaitü, renewing his claims to Azerbaijan on 13 October 1312. Öljaitü also supported the latter during Chagatai-Yuan war in 1314, annexing Southern Afghanistan after expelling Qara'unas.[11] After repelling Chagatai armies, he appointed his son Abu Sa'id to govern Khorasan and Mazandaran in 1315 with the Uyghur noble Amir Sevinch as his guardian. Another descendant of Jochi Qasar, Baba Oghul arrived from Central Asia in the same year, pillaging Khwarazm on his way, causing much disturbance. Upon protests from Golden Horde emissaries, Öljaitü had to execute Baba, claiming he was not informed of such unauthorized acts.[13]

Öljaitü's reign is also remembered for a brief effort at Ilkhanid invasion of Hijaz. Humaydah ibn Abi Numayy, arrived at the Ilkhanate court in 1315, ilkhan on his part provided Humaydah an army of several thousand Mongols and Arabs under the command of Sayyid Talib al-Dilqandi to bring the Hijaz under Ilkhanid control. He also planned to exhume the bodies of the caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar from their graves in Medina. However, soon after the expedition passed Basra they received news of ilkhan's death, and a large part of the army deserted. The remainder – three hundred Mongols and four hundred Arabs – were crushed by a horde of four thousand Bedouin led Muhammad ibn Isa (brother of Muhanna ibn Isa) in March 1317.[19]

Death

He died in Soltaniyeh on 17 December 1316,[11] having reigned for twelve years and nine months. Afterwards, Rashid al-Din Hamadani was accused of having caused his death by poisoning and was executed. Oljeitu was succeeded by his son Abu Sa'id.

Religion

Öljaitü had been professing Buddhism, Christianity and Islam throughout his life. After succeeding his brother, Öljeitu became influenced by Shi'a theologians Al-Hilli and Maitham Al Bahrani.[20][21] Although another source indicates he converted to Islam through the persuasions of his wife.[22] Upon Al-Hilli's death, Oljeitu transferred his teacher's remains from Baghdad to a domed shrine he built in Soltaniyeh. Later, alienated by the factional strife between the Sunnis, Oljeitu changed his school of thought to Shi'a Islam in 1310.[23] At some point, he even considered converting to Tengriism in early 1310.[15] Mamluk historian al-Safadi mentioned in his biographical dictionary Aʻyan al-ʻAsr that Oljeitu had once again became Sunni in the last few years before his death in the Ramadan of 716 AH.[24]

Legacy

He oversaw the end of construction of city of Soltaniyeh[18] on Qongqur-Oleng plains in 1306. In 1309, Öljeitu founded a Dar al-Sayyedah ("Sayyed's lodge") in Shiraz, Iran, and endowed it with an income of 10,000 Dinars a year. His tomb in Soltaniyeh, 300 km west of Tehran, remains the best known monument of Ilkhanid Persia. According to Ruy González de Clavijo, his body was later exhumed by Miran Shah.[25]

Relations with Europe

Trade contacts

Trading contacts with European powers were very active during the reign of Öljeitu. The Genoese had first appeared in the capital of Tabriz in 1280, and they maintained a resident Consul by 1304. Oljeitu also gave full trading rights to the Venetians through a treaty in 1306 (another such treaty with his son Abu Said was signed in 1320).[26] According to Marco Polo, Tabriz was specialized in the production of gold and silk, and Western merchants could purchase precious stones in quantities.[26]

Military alliance

After his predecessors Arghun and Ghazan, Öljeitu continued diplomatic overtures with the West, and re-stated Mongol hopes for an alliance between the Christian nations of Europe and the Mongols against the Mamluks, even though Öljeitu himself had converted to Islam.

1305 embassy

In April 1305, he sent a Mongol embassy led by Buscarello de Ghizolfi to the French king Philip IV of France,[27] Pope Clement V, and Edward I of England. The letter to Philip IV, the only one to have survived, describes the virtues of concord between the Mongols and the Franks:

"We, Sultan Oljaitu. We speak. We, who by the strength of the Sky, rose to the throne (...), we, descendant of Genghis Khan (...). In truth, there cannot be anything better than concord. If anybody was not in concord with either you or ourselves, then we would defend ourselves together. Let the Sky decide!"

— Extract from the letter of Oljeitu to Philip the Fair. French national archives.[28]

He also explained that internal conflicts between the Mongols were now over:

"Now all of us, Timur Khagan, Tchapar, Toctoga, Togba and ourselves, main descendants of Gengis-Khan, all of us, descendants and brothers, are reconciled through the inspiration and the help of God. So that, from Nangkiyan (China) in the Orient, to Lake Dala our people are united and the roads are open."

— Extract from the letter of Oljeitu to Philip the Fair. French national archives.[29]

This message reassured the European nations that the Franco-Mongol alliance, or at least attempts towards such an alliance, had not ceased, even though the Khans had converted to Islam.[30]

1307 embassy

Another embassy was sent to the West in 1307, led by Tommaso Ugi di Siena, an Italian described as Öljeitu's ildüchi ("Sword-bearer").[31] This embassy encouraged Pope Clement V to speak in 1307 of the strong possibility that the Mongols could remit the Holy Land to the Christians, and to declare that the Mongol embassy from Öljeitu "cheered him like spiritual sustenance".[32] Relations were quite warm: in 1307, the Pope named John of Montecorvino the first Archbishop of Khanbalik and Patriarch of the Orient.[33]

European nations accordingly prepared a crusade, but were delayed. A memorandum drafted by the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitallers Guillaume de Villaret about military plans for a Crusade envisaged a Mongol invasion of Syria as a preliminary to a Western intervention (1307/8).[34]

Military operation 1308

Byzantine Emperor Andronicus II gave a daughter in marriage to Oljeitu and asked the Ilkhan's assistance against growing the power of the Ottomans. In 1305, Oljeitu promised his father in law 40,000 men, and in 1308 dispatched 30,000 men to recover many Byzantine towns in Bithynia and the Ilkhanid army crushed a detachment of Osman I.[35]

1313 embassy

On 4 April 1312, a Crusade was promulgated by Pope Clement V at the Council of Vienne. Another embassy was sent by Oljeitu to the West and to Edward II in 1313.[36] That same year, the French king Philippe le Bel "took the cross", making the vow to go on a Crusade in the Levant, thus responding to Clement V's call for a Crusade. He was however warned against leaving by Enguerrand de Marigny,[37] and died soon after in a hunting accident.[38]

A final settlement with the Mamluks would only be found when Oljeitu's son signed the Treaty of Aleppo with the Mamluks in 1322.

Family

Öljaitü had thirteen consorts with several issues, albeit only one surviving son and daughter:

- Terjughan Khatun, daughter of Lagzi Güregen (son of Arghun Aqa) and Baba Khatun

- Dowlandi Khatun (died 1314) married on 30 September 1305 to Amir Chupan

- Eltuzmish Khatun (m. 1296, d. 10 October 1308, buried in Dome of Sultaniyeh[39]), daughter of Qutlugh Timur Kurkan of the Khongirad, sister of Taraqai Kurkan (widow of Abaqa Khan and previously that of Gaykhatu Khan)

- Bastam (1297 - 15 October 1309) - married Uljay Qutlugh Khatun on 12 January 1305 (named after Bayazid Bastami)

- Muhammad Tayfur (b. 3 December 1306) (named after Bayazid Bastami)

- Sati Beg Khatun - with Eltuzmish Khatun, married firstly on 6 September 1319 to Amir Chupan, married secondly in 1336 to Arpa Ke'un, married thirdly in 1339 to Suleiman Khan;

- Hajji Khatun, daughter of Chichak, son of Sulamish and Todogaj Khatun;

- Qutlughshah Khatun (betrothed 18 March 1305, m. 20 June 1305), daughter of Irinjin,[40] and Konchak Khatun;

- Sultan Khatun

- Bulughan Khatun Khurasani (m. 23 June 1305, d. 5 January 1310 in Baghdad), daughter of Tasu and Mangli Tegin Khatun (widow of Ghazan Khan)

- Kunjuskab Khatun (m. 1305), daughter of Shadi Kurkan and Orqudaq Khatun (widow of Ghazan Khan)

- Oljatai Khatun (m. 1306, died 4 October 1315) - sister of Hajji Khatun (widow of Arghun Khan)

- Abu'l Khayr (b. 1305, died in infancy, buried next to Ghazan in Shanb Ghazan)

- Soyurghatmish Khatun, daughter of Amir Husayn Jalayir, and sister of Hasan Buzurg;

- Qongtai Khatun, daughter of Timur Kurkan;

- Dunya Khatun, daughter of al-Malik al-Malik Najm ad-Din Ghazi, ruler of Mardin;

- Adil Shah Khatun, daughter of Amir Sartaq, the amir-ordu of Bulughan Khatun Buzurg;[41]

- Sulayman Shah (d. 10 August 1310)

- Despina Khatun, daughter of Andronikos II Palaiologos;[42]

- Tugha Khatun, a lady accused of having an affair with Demasq Kaja;

Öljaitü also allegedly had an additional son, Ilchi who was claimed as an ancestor of the Arghun and Tarkhan dynasties of Afghanistan and India.[43]

See also

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b c Kāshānī, ʻAbd Allāh ibn ʻAlī.; كاشانى، عبد الله بن على. (2005). Tārīkh-i Ūljāytū (in Persian). Hambalī, Mahīn., همبلى، مهين. (Chāp-i 2 ed.). Tehran: Shirkat Intishārat-i ʻIlmī va Farhangī. ISBN 964-445-718-8. OCLC 643519562.

- ^ Komaroff, Linda (2012). Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan. BRILL. p. 19. ISBN 978-90-04-24340-8.

- ^ Hope 2016, p. 185.

- ^ Ryan, James D. (November 1998). "Christian wives of Mongol khans: Tartar queens and missionary expectations in Asia". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 8 (9): 411–421. doi:10.1017/s1356186300010506. S2CID 162220753.

- ^ Dashdondog, Bayarsaikhan (2010-12-07). The Mongols and the Armenians (1220-1335). BRILL. p. 203. ISBN 978-90-04-18635-4.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (2014-05-01). The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410. Routledge. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-317-87899-5.

- ^ "Arghun had one of his sons baptized, Khordabandah, the future Öljeitu, and in the Pope's honor, went as far as giving him the name Nicholas", Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, Jean-Paul Roux, p. 408.

- ^ Özgüdenli, Osman Gazi. "OLCAYTU HAN - TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi". islamansiklopedisi.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- ^ Rashīd al-Dīn Ṭabīb, Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh, ed. Muḥammad Raushan and Muṣṭafa Mūsavī (Tehran: Alburz, 1994), p. 1324

- ^ "ALĀFRANK – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- ^ a b c d e f The Cambridge history of Iran. Volume V.. Fisher, W. B. (William Bayne). Cambridge: University Press. 1968–1991. pp. 397–406. ISBN 0-521-06935-1. OCLC 745412.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Tulibayeva, Zhuldyz M. (2018-06-26). "Mirza Ulugh Beg on the Chinggisids on the Throne of Iran: The Reigns of Öljaitü Khan and Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan". Golden Horde Review. 6 (2): 422–438. doi:10.22378/2313-6197.2018-6-2.422-438. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- ^ a b Jackson, Peter, 1948 January 27- (4 April 2017). The Mongols & the Islamic world : from conquest to conversion. New Haven. pp. 201–206. ISBN 978-0-300-22728-4. OCLC 980348050.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, p. 315.

- ^ a b Kamola, Stefan (2013-07-25). Rashīd al-Dīn and the making of history in Mongol Iran (PhD thesis). pp. 204–224. hdl:1773/23424.

- ^ Peacock, A. C. S. (2019-10-17). Islam, Literature and Society in Mongol Anatolia. Cambridge University Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-108-49936-1.

- ^ Brill Online. Encyclopaedia of Islam. Second edition Second edition. Leiden: Brill Online. OCLC 624382576.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Stevens, John. The history of Persia. Containing, the lives and memorable actions of its kings from the first erecting of that monarchy to this time; an exact Description of all its Dominions; a curious Account of India, China, Tartary, Kermon, Arabia, Nixabur, and the Islands of Ceylon and Timor; as also of all Cities occasionally mentioned, as Schiras, Samarkand, Bokara, &c. Manners and Customs of those People, Persian Worshippers of Fire; Plants, Beasts, Product, and Trade. With many instructive and pleasant digressions, being remarkable Stories or Passages, occasionally occurring, as Strange Burials; Burning of the Dead; Liquors of several Countries; Hunting; Fishing; Practice of Physick; famous Physicians in the East; Actions of Tamerlan, &c. To which is added, an abridgment of the lives of the kings of Harmuz, or Ormuz. The Persian history written in Arabick, by Mirkond, a famous Eastern Author that of Ormuz, by Torunxa, King of that Island, both of them translated into Spanish, by Antony Teixeira, who lived several Years in Persia and India; and now rendered into English.

- ^ al-Najm Ibn Fahd, Itḥāf al-wará, 3/155–156

- ^ Alizadeh, Saeed; Alireza Pahlavani; Ali Sadrnia. Iran: A Chronological History. p. 137.

- ^ Al Oraibi, Ali (2001). "Rationalism in the school of Bahrain: a historical perspective". In Lynda Clarke (ed.). Shīʻite Heritage: Essays on Classical and Modern Traditions. Global Academic Publishing. p. 336.

- ^ The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, p. 197.

- ^ Ann K.S. Lambton, Continuity and Change in Medieval Persia, ed. Ehsan Yarshater, (Bibliotheca Persica, 1988), p. 255.

- ^ الصفدي, صلاح الدين (1998). أعيان العصر وأعوان النصر. Vol. 4. دار الفكر المعاصر. p. 314.

- ^ González de Clavijo, Ruy (2009). Embassy to Tamerlane, 1403-1406. Le Strange, G. (Guy), 1854-1933. Kilkerran: Hardinge Simpole. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-84382-198-4. OCLC 465363153.

- ^ a b Jackson, p. 298.

- ^ Mostaert and Cleaves, pp. 56–57, Source Archived 2008-04-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quoted in Jean-Paul Roux, Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, p. 437.

- ^ Source

- ^ Jean-Paul Roux, in Histoire de l'Empire Mongol ISBN 2-213-03164-9: "The Occident was reassured that the Mongol alliance had not ceased with the conversion of the Khans to Islam. However, this alliance could not have ceased. The Mamelouks, through their repeated military actions, were becoming a strong enough danger to force Iran to maintain relations with Europe.", p. 437.

- ^ Peter Jackson, p. 173.

- ^ Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, p. 171.

- ^ Foltz, p.131

- ^ Peter Jackson, p. 185.

- ^ I. Heath, Byzantine Armies: AD 1118–1461, pp. 24–33.

- ^ Peter Jackson, p. 172.

- ^ Jean Richard, "Histoire des Croisades", p. 485.

- ^ Richard, p. 485.

- ^ Blair, Sheila (2014). Text and image in medieval Persian art. Edinburgh. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-7486-5578-6. OCLC 858824780.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lambton, Ann K. S. (January 1, 1988). Continuity and Change in Medieval Persia. SUNY Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-887-06133-2.

- ^ Hillenbrand, Robert; Peacock, A. C. S.; Abdullaheva, Firuza (January 29, 2014). Ferdowsi, the Mongols and the History of Iran: Art, Literature and Culture from Early Islam to Qajar Persia. I. B. Tauris. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-780-76015-5.

- ^ Korobeinikov, Dimitri (2014). Byzantium and the Turks in the Thirteenth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-198-70826-1.

- ^ Mahmudul Hasan Siddiqi, History of the Arghuns and Tarkhans of Sind, 1507-1593 (1972), p. 249.

References

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-4671-9.

- (ISBN 0-295-98391-4) page 87

- Foltz, Richard, Religions of the Silk Road, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- Jackson, Peter, The Mongols and the West, Pearson Education, ISBN 0-582-36896-0

- Roux, Jean-Paul, Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, Fayard, ISBN 2-213-03164-9

- Ibn Fahd, Najm al-Din Umar ibn Muḥammad (1983–1984) [Composed before 1481]. Shaltūt, Fahīm Muḥammad (ed.). Itḥāf al-wará bi-akhbār Umm al-Qurá إتحاف الورى بأخبار أم القرى (in Arabic) (1st ed.). Makkah: Jāmi‘at Umm al-Qurá, Markaz al-Baḥth al-‘Ilmī wa-Iḥyā’ al-Turāth al-Islāmī, Kullīyat al-Sharīʻah wa-al-Dirāsāt al-Islāmīyah.

- Hope, Michael (2016). Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198768593.