| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Crux |

| Pronunciation | /ˈeɪkrʌks/[citation needed] |

| Right ascension | 12h 26m 35.89522s[1] |

| Declination | −63° 05′ 56.7343″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 0.76[2] (1.33 + 1.75)[3] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | B0.5IV + B1V[4] |

| B−V color index | −0.26[2] |

| Variable type | β Cep[5] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −11.2 / −0.6[6] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −35.83[1] mas/yr Dec.: −14.86[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 10.13 ± 0.50 mas[1] |

| Distance | 320 ± 20 ly (99 ± 5 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −3.77[7] (−2.2 + −2.7[8]) |

| Orbit[9] | |

| Primary | α Crucis Aa |

| Companion | α Crucis Ab |

| Period (P) | 75.7794±0.0037 d |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.46±0.03 |

| Periastron epoch (T) | 2,417,642.3±1.6 JD |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (secondary) | 21±6° |

| Semi-amplitude (K1) (primary) | 41.7±1.2 km/s |

| Details | |

| α1 | |

| Mass | 17.80 + 6.05[3] M☉ |

| Radius | 7.29 ± 0.34[5][a] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 31,110+3,190 −2,910[5] L☉ |

| Temperature | 28,840[5] K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 124[5] km/s |

| α2 | |

| Mass | 15.52[3] M☉ |

| Radius | 5.53[10] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 16,000[11] L☉ |

| Temperature | 28,000[12] K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 200[12] km/s |

| Age | 10.8[13] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| α1 Cru: Acrux, 26 G. Crucis, FK5 462, GC 16952, HD 108248, HR 4730 | |

| α2 Cru: 27 G. Crucis, GC 16953, HD 108249, HR 4731, 2MASS J12263615-6305571 | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | α Cru |

| α1 Cru | |

| α2 Cru | |

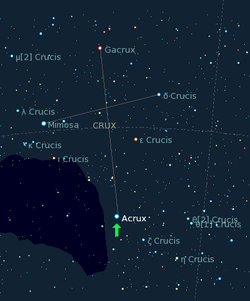

Acrux is the brightest star in the southern constellation of Crux. It has the Bayer designation α Crucis, which is Latinised to Alpha Crucis and abbreviated Alpha Cru or α Cru. With a combined visual magnitude of +0.76, it is the 13th-brightest star in the night sky. It is the most southerly star of the asterism known as the Southern Cross and is the southernmost first-magnitude star, 2.3 degrees more southerly than Alpha Centauri.[14] This system is located at a distance of 321 light-years from the Sun.[1][15]

To the naked eye Acrux appears as a single star, but it is actually a multiple star system containing six components. Through optical telescopes, Acrux appears as a triple star, whose two brightest components are visually separated by about 4 arcseconds and are known as Acrux A and Acrux B, α1 Crucis and α2 Crucis, or α Crucis A and α Crucis B. Both components are B-type stars, and are many times more massive and luminous than the Sun. This system was the second ever to be recognized as a binary, in 1685 by a Jesuit priest.[16] α1 Crucis is itself a spectroscopic binary with components designated α Crucis Aa (officially named Acrux, historically the name of the entire system)[17][18] and α Crucis Ab. Its two component stars orbit every 76 days at a separation of about 1 astronomical unit (AU).[11] HR 4729, also known as Acrux C, is a more distant companion, forming a triple star through small telescopes. C is also a spectroscopic binary, which brings the total number of stars in the system to at least five.

Nomenclature

α Crucis (Latinised to Alpha Crucis) is the system's Bayer designation; α1 and α2 Crucis, those of its two main components stars. The designations of these two constituents as Acrux A and Acrux B and those of A's components—Acrux Aa and Acrux Ab—derive from the convention used by the Washington Multiplicity Catalog (WMC) for multiple star systems,[dubious – discuss] and adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).[19][unreliable source?]

The historical name Acrux for α1 Crucis is an "Americanism" coined in the 19th century, but entering common use only by the mid 20th century.[20][better source needed] In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[21] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN states that in the case of multiple stars the name should be understood to be attributed to the brightest component by visual brightness.[22] The WGSN approved the name Acrux for the star Acrux Aa on 20 July 2016 and it is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[18]

Since Acrux is at −63° declination, making it the southernmost first-magnitude star, it is only visible south of latitude 27° North. It barely rises from cities such as Miami, United States, or Karachi, Pakistan (both around 25°N) and not at all from New Orleans, United States, or Cairo, Egypt (both about 30°N). Because of Earth's axial precession, the star was visible to ancient Hindu astronomers in India who named it Tri-shanku. It was also visible to the ancient Romans and Greeks, who regarded it as part of the constellation of Centaurus.[23]

In Chinese, 十字架 (Shí Zì Jià, "Cross"), refers to an asterism consisting of Acrux, Mimosa, Gamma Crucis and Delta Crucis.[24] Consequently, Acrux itself is known as 十字架二 (Shí Zì Jià èr, "the Second Star of Cross").[25]

This star is known as Estrela de Magalhães ("Star of Magellan") in Portuguese.[26]

Stellar properties

The two components, α1 and α2 Crucis, are separated by 4 arcseconds. α1 is magnitude 1.40 and α2 is magnitude 2.09, both early class B stars, with surface temperatures of about 28,000 and 26,000 K, respectively. Their luminosities are 25,000 and 16,000 times that of the Sun. α1 and α2 orbit over such a long period that motion is only barely seen. From their minimum separation of 430 astronomical units, the period is estimated to be around 1,500 years.[3]

α1 is itself a spectroscopic binary star, with its components thought to be around 14 and 10 times the mass of the Sun and orbiting in only 76 days at a separation of about 1 AU. The masses of α2 and the brighter component of α1 suggest that the stars will someday expand into blue and red supergiants (similar to Betelgeuse and Antares) before exploding as supernovae.[11] Component Ab may perform electron capture in the degenerate O+Ne+Mg core and trigger a supernova explosion,[27][28] otherwise it will become a massive white dwarf.[11]

Photometry with the TESS satellite has shown that one of the stars in the α Crucis system is a β Cephei variable, although α1 and α2 Crucis are too close for TESS to resolve and determine which one is the pulsator.[5]

Rizzuto and colleagues determined in 2011 that the α Crucis system was 66% likely to be a member of the Lower Centaurus–Crux sub-group of the Scorpius–Centaurus association. It was not previously seen to be a member of the group.[29] A bow shock is present around α Crucis, and is visible in the infrared spectrum, but is not aligned with α Crucis; the bow shock likely formed from large-scale motions in the interstellar matter.[30]

The cooler, less-luminous B-class star HR 4729 (HD 108250) lies 90 arcseconds away from triple star system α Crucis and shares its motion through space, suggesting it may be gravitationally bound to it, and it is therefore generally assumed to be physically associated.[31][32] It is itself a spectroscopic binary system, sometimes catalogued as component C (Acrux C) of the Acrux multiple system. Another fainter visual companion listed as component D or Acrux D. A further seven faint stars are also listed as companions out to a distance of about two arc-minutes.[33]

On 2 October 2008, the Cassini–Huygens spacecraft resolved three of the components (A, B and C) of the multiple star system as Saturn's disk occulted it.[34][35]

| Separation (arcsec) |

Projected separation (AU) |

Orbital period |

Spectral type |

Mass (M☉) |

App. mag. (V) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrux ABC | HR 4729 ABC (Acrux C & CP) [orbit note 1] |

α1 Crucis CP | 2.1 | 220 | 930 years | M0V | 0.47 | 15.0 | |

| HR 4729 AB | HR 4729 A | 0.00046 | 0.048 | 1.225 days | B4V | 8.68 | 4.9 (combined) | ||

| HR 4729 B | G?V | 0.97 | |||||||

| Acrux AB (α1 and α2) [orbit note 1] |

α2 Crucis | 4.4 | 460 | 1470 years | B1Vn | 15.52 | 1.8 | ||

| α1 Crucis | Acrux Aa | 0.0094 | 0.99 | 75.8 days | B0.5IV | 17.80 | 1.3 (combined) | ||

| Acrux ab | B7?V | 4.49 | |||||||

In culture

Acrux is represented in the flags of Australia, New Zealand, Samoa, and Papua New Guinea as one of five stars that compose the Southern Cross. It is also featured in the flag of Brazil, along with 26 other stars, each of which represents a state; Acrux represents the state of São Paulo.[36] As of 2015, it is also represented on the cover of the Brazilian passport.

The Brazilian oceanographic research vessel Alpha Crucis is named after the star.

See also

Notes

- ^ Applying the Stefan–Boltzmann law with a nominal solar effective temperature of 5,772 K:

- .

References

- ^ a b c d e f van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007), "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 474 (2): 653–664, arXiv:0708.1752, Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357, S2CID 18759600

- ^ a b Corben, P. M. (1966). "Photoelectric magnitudes and colours for bright southern stars". Monthly Notes of the Astron. Soc. Southern Africa. 25: 44. Bibcode:1966MNSSA..25...44C.

- ^ a b c d Tokovinin, A. A. (1997). "MSC - a catalogue of physical multiple stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. 124 (1): 75–84. Bibcode:1997A&AS..124...75T. doi:10.1051/aas:1997181. ISSN 0365-0138.

- ^ Houk, Nancy (1979), "Michigan catalogue of two-dimensional spectral types for the HD stars", Ann Arbor: Dept. Of Astronomy, 1, Bibcode:1978mcts.book.....H

- ^ a b c d e f Sharma, Awshesh N.; Bedding, Timothy R.; Saio, Hideyuki; White, Timothy R. (2022). "Pulsating B stars in the Scorpius–Centaurus Association with TESS". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 515 (1): 828–840. arXiv:2203.02582. Bibcode:2022MNRAS.515..828S. doi:10.1093/mnras/stac1816.

- ^ Wilson, Ralph Elmer (1953). "General Catalogue of Stellar Radial Velocities". Carnegie Institute Washington D.C. Publication. Bibcode:1953GCRV..C......0W.

- ^ Kaltcheva, N. T.; Golev, V. K.; Moran, K. (2014). "Massive stellar content of the Galactic supershell GSH 305+01-24". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 562: A69. arXiv:1312.5592. Bibcode:2014A&A...562A..69K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321454. S2CID 54222753.

- ^ Van De Kamp, Peter (1953). "The Twenty Brightest Stars". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 65 (382): 30. Bibcode:1953PASP...65...30V. doi:10.1086/126523.

- ^ Thackeray, A. D.; Wegner, G. (April 1980), "An improved spectroscopic orbit for α1 Crucis", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 191 (2): 217–220, Bibcode:1980MNRAS.191..217T, doi:10.1093/mnras/191.2.217

- ^ Lang, Kenneth R. (2006), Astrophysical formulae, Astronomy and astrophysics library, vol. 1 (3 ed.), Birkhäuser, ISBN 3-540-29692-1. The radius (R*) is given by:

The angular diameter used (0.52 milliarcseconds) is from CADARS. Distance (99 parsecs) is from Hipparcos.

- ^ a b c d Kaler, James B. (2002). "Acrux". The Hundred Greatest Stars. pp. 4–5. doi:10.1007/0-387-21625-1_2. ISBN 978-0-387-95436-3.

- ^ a b Dravins, Dainis; Jensen, Hannes; Lebohec, Stephan; Nuñez, Paul D. (2010). "Stellar intensity interferometry: Astrophysical targets for sub-milliarcsecond imaging". Optical and Infrared Interferometry II. Proceedings of the SPIE. Vol. 7734. pp. 77340A. arXiv:1009.5815. Bibcode:2010SPIE.7734E..0AD. doi:10.1117/12.856394. S2CID 55641060.

- ^ Tetzlaff, N.; Neuhäuser, R.; Hohle, M. M. (2011). "A catalogue of young runaway Hipparcos stars within 3 kpc from the Sun". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 410 (1): 190–200. arXiv:1007.4883. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.410..190T. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17434.x. S2CID 118629873.

- ^ Bordeleau, André G. (12 August 2013). "Federative Republic of Brazil: Constellations in the Breeze". Flags of the Night Sky. New York: Springer. pp. 1–72. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0929-8_1. ISBN 978-1-4614-0928-1.

- ^ Perryman, Michael (2010), The Making of History's Greatest Star Map, Astronomers' Universe, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, Bibcode:2010mhgs.book.....P, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11602-5, ISBN 978-3-642-11601-8

- ^ "A Story about Crux | Centre for Astronomical Heritage (CfAH)".

- ^ Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006). A Dictionary of Modern star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations (2nd rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Sky Pub. ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ^ a b "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ Hessman, F. V.; Dhillon, V. S.; Winget, D. E.; Schreiber, M. R.; Horne, K.; Marsh, T. R.; Guenther, E.; Schwope, A.; Heber, U. (2010). "On the naming convention used for multiple star systems and extrasolar planets". arXiv:1012.0707 [astro-ph.SR].

- ^ Memoirs of the Rev. Walter M. Lowrie: missionary to China (1849), p. 93. Described as an "Americanism" in The Geographical Journal, vol. 92, Royal Geographical Society, 1938.

- ^ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 2" (PDF). Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ Richard Hinckley Allen, Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, Dover Books, 1963.

- ^ (in Chinese) 中國星座神話, written by 陳久金. Published by 台灣書房出版有限公司, 2005, ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ^ (in Chinese) 香港太空館 - 研究資源 - 亮星中英對照表 Archived 2010-09-03 at the Wayback Machine, Hong Kong Space Museum. Accessed on line November 23, 2010.

- ^ Silva, Guilherme Marques dos Santos; Ribas, Felipe Braga; Freitas, Mário Sérgio Teixeira de (2008). "Transformação de coordenadas aplicada à construção da maquete tridimensional de uma constelação". Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Física. 30: 1306.1 – 1306.7. doi:10.1590/S1806-11172008000100007.

- ^ Nomoto, K. (1984). "Evolution of 8-10 solar mass stars toward electron capture supernovae. I - Formation of electron-degenerate O + NE + MG cores". Astrophysical Journal. 277: 791. Bibcode:1984ApJ...277..791N. doi:10.1086/161749.

- ^ S. E. Woosley, Alexander Heger (May 25, 2015). "The Remarkable Deaths of 9 - 11 Solar Mass Stars". Astrophysics. 810 (1): 34. arXiv:1505.06712. Bibcode:2015ApJ...810...34W. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/810/1/34. S2CID 119163256.

- ^ Rizzuto, Aaron; Ireland, Michael; Robertson, J. G. (October 2011), "Multidimensional Bayesian membership analysis of the Sco OB2 moving group", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 416 (4): 3108–3117, arXiv:1106.2857, Bibcode:2011MNRAS.416.3108R, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19256.x, S2CID 54510608.

- ^ Torosyan, M.; Azatyan, N.; Nikoghosyan, E.; Samsonyan, A.; Andreasyan, D. (2024). "The runaway nature and origin of α Crucis system". Communications of the Byurakan Astrophysical Observatory. 71: 42–47. arXiv:2407.09934. Bibcode:2024CoBAO..71...42T. doi:10.52526/25792776-24.71.1-42.

- ^ Shatsky, N.; Tokovinin, A. (2002). "The mass ratio distribution of B-type visual binaries in the Sco OB2 association". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 382: 92–103. arXiv:astro-ph/0109456. Bibcode:2002A&A...382...92S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20011542. S2CID 16697655.

- ^ Eggleton, Peter; Tokovinin, A. (2008). "A catalogue of multiplicity among bright stellar systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 389 (2): 869–879. arXiv:0806.2878. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.389..869E. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13596.x. S2CID 14878976.

- ^ Mason, Brian D.; Wycoff, Gary L.; Hartkopf, William I.; Douglass, Geoffrey G.; Worley, Charles E. (2001). "The 2001 US Naval Observatory Double Star CD-ROM. I. The Washington Double Star Catalog". The Astronomical Journal. 122 (6): 3466–3471. Bibcode:2001AJ....122.3466M. doi:10.1086/323920.

- ^ "Cassini raw image". NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- ^ Cassini "Kodak Moments" - Unmanned Spaceflight.com. Retrieved 2008-10-21

- ^ "Astronomy of the Brazilian Flag". FOTW Flags Of The World website.

External links

- http://jumk.de/astronomie/big-stars/acrux.shtml

- http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/A/Acrux.html