In music, metre (British spelling) or meter (American spelling) refers to regularly recurring patterns and accents such as bars and beats. Unlike rhythm, metric onsets are not necessarily sounded, but are nevertheless implied by the performer (or performers) and expected by the listener.[not verified in body]

A variety of systems exist throughout the world for organising and playing metrical music, such as the Indian system of tala and similar systems in Arabic and African music.

Western music inherited the concept of metre from poetry,[1][2] where it denotes the number of lines in a verse, the number of syllables in each line, and the arrangement of those syllables as long or short, accented or unaccented.[1][2] The first coherent system of rhythmic notation in modern Western music was based on rhythmic modes derived from the basic types of metrical unit in the quantitative metre of classical ancient Greek and Latin poetry.[3]

Later music for dances such as the pavane and galliard consisted of musical phrases to accompany a fixed sequence of basic steps with a defined tempo and time signature. The English word "measure", originally an exact or just amount of time, came to denote either a poetic rhythm, a bar of music, or else an entire melodic verse or dance[4] involving sequences of notes, words, or movements that may last four, eight or sixteen bars.[citation needed]

Metre is related to and distinguished from pulse, rhythm (grouping), and beats:

Meter is the measurement of the number of pulses between more or less regularly recurring accents. Therefore, in order for meter to exist, some of the pulses in a series must be accented—marked for consciousness—relative to others. When pulses are thus counted within a metric context, they are referred to as beats.[5]

Metric structure

The term metre is not very precisely defined.[1] Stewart MacPherson preferred to speak of "time" and "rhythmic shape",[6] while Imogen Holst preferred "measured rhythm".[7] However, Justin London has written a book about musical metre, which "involves our initial perception as well as subsequent anticipation of a series of beats that we abstract from the rhythm surface of the music as it unfolds in time".[8] This "perception" and "abstraction" of rhythmic bar is the foundation of human instinctive musical participation, as when we divide a series of identical clock-ticks into "tick–tock–tick–tock".[1] "Rhythms of recurrence" arise from the interaction of two levels of motion, the faster providing the pulse and the slower organizing the beats into repetitive groups.[9] In his book The Rhythms of Tonal Music, Joel Lester notes that, "[o]nce a metric hierarchy has been established, we, as listeners, will maintain that organization as long as minimal evidence is present".[10]

"Meter may be defined as a regular, recurring pattern of strong and weak beats. This recurring pattern of durations is identified at the beginning of a composition by a meter signature (time signature). ... Although meter is generally indicated by time signatures, it is important to realize that meter is not simply a matter of notation".[11] A definition of musical metre requires the possibility of identifying a repeating pattern of accented pulses – a "pulse-group" – which corresponds to the foot in poetry.[citation needed] Frequently a pulse-group can be identified by taking the accented beat as the first pulse in the group and counting the pulses until the next accent.[12][1]

Frequently metres can be subdivided into a pattern of duples and triples.[12][1]

For example, a 3

4 metre consists of three units of a 2

8 pulse group, and a 6

8 metre consists of two units of a 3

8 pulse group. In turn, metric bars may comprise 'metric groups' - for example, a musical phrase or melody might consist of two bars x 3

4.[13]

The level of musical organisation implied by musical metre includes the most elementary levels of musical form.[6] Metrical rhythm, measured rhythm, and free rhythm are general classes of rhythm and may be distinguished in all aspects of temporality:[14]

- Metrical rhythm, by far the most common class in Western music, is where each time value is a multiple or fraction of a fixed unit (beat, see paragraph below), and normal accents reoccur regularly, providing systematic grouping (bars, divisive rhythm).

- Measured rhythm is where each time value is a multiple or fraction of a specified time unit but there are not regularly recurring accents (additive rhythm).

- Free rhythm is where the time values are not based on any fixed unit; since the time values lack a fixed unit, regularly recurring accents are no longer a possibility.

Some music, including chant, has freer rhythm, like the rhythm of prose compared to that of verse.[1] Some music, such as some graphically scored works since the 1950s and non-European music such as Honkyoku repertoire for shakuhachi, may be considered ametric.[15] The music term senza misura is Italian for "without metre", meaning to play without a beat, using time (e.g. seconds elapsed on an ordinary clock) if necessary to determine how long it will take to play the bar.[16][page needed]

Metric structure includes metre, tempo, and all rhythmic aspects that produce temporal regularity or structure, against which the foreground details or durational patterns of any piece of music are projected.[17] Metric levels may be distinguished: the beat level is the metric level at which pulses are heard as the basic time unit of the piece.[citation needed] Faster levels are division levels, and slower levels are multiple levels.[17] A rhythmic unit is a durational pattern which occupies a period of time equivalent to a pulse or pulses on an underlying metric level.[citation needed]

Frequently encountered types of metre

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

Metres classified by the number of beats per measure

Duple and quadruple metre

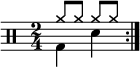

In duple metre, each measure is divided into two beats, or a multiple thereof (quadruple metre).

For example, in the time signature 2

4, each bar contains two (2) quarter-note (4) beats. In the time signature 6

8, each bar contains two dotted-quarter-note beats.

Corresponding quadruple metres are 4

4, which has four quarter-note beats per measure, and 12

8, which has four dotted-quarter-note beats per bar.

Triple metre

Triple metre is a metre in which each bar is divided into three beats, or a multiple thereof. For example, in the time signature 3

4, each bar contains three (3) quarter-note (4) beats, and with a time signature of 9

8, each bar contains three dotted-quarter beats.

More than four beats

Metres with more than four beats are called quintuple metres (5), sextuple metres (6), septuple metres (7), etc.

In classical music theory it is presumed that only divisions of two or three are perceptually valid, so a metre not divisible by 2 or 3, such as quintuple metre, say 5

4, is assumed to either be equivalent to a measure of 3

4 followed by a measure of 2

4, or the opposite: 2

4 then 3

4. Higher metres which are divisible by 2 or 3 are considered equivalent to groupings of duple or triple metre measures; thus, 6

4, for example, is rarely used because it is considered equivalent to two measures of 3

4. See: hypermetre and additive rhythm and divisive rhythm.

Higher metres are used more commonly in analysis, if not performance, of cross-rhythms, as lowest number possible which may be used to count a polyrhythm is the lowest common denominator (LCD) of the two or more metric divisions. For example, much African music is recorded in Western notation as being in 12

8, the LCD of 4 and 3.

Metres classified by the subdivisions of a beat

Simple metre and compound metre are distinguished by the way the beats are subdivided.

Simple metre

Simple metre (or simple time) is a metre in which each beat of the bar divides naturally into two (as opposed to three) equal parts. The top number in the time signature will be 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.

For example, in the time signature 3

4, each bar contains three quarter-note beats, and each of those beats divides into two eighth notes, making it a simple metre. More specifically, it is a simple triple metre because there are three beats in each measure; simple duple (two beats) or simple quadruple (four) are also common metres.

Compound metre

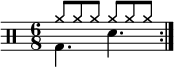

Compound metre (or compound time), is a metre in which each beat of the bar divides naturally into three equal parts. That is, each beat contains a triple pulse.[18] The top number in the time signature will be 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 24, etc.

Compound metres are written with a time signature that shows the number of divisions of beats in each bar as opposed to the number of beats. For example, compound duple (two beats, each divided into three) is written as a time signature with a numerator of six, for example, 6

8. Contrast this with the time signature 3

4, which also assigns six eighth notes to each measure, but by convention connotes a simple triple time: 3 quarter-note beats.

Examples of compound metre include 6

8 (compound duple metre), 9

8 (compound triple metre), and 12

8 (compound quadruple metre).

Although 3

4 and 6

8 are not to be confused, they use bars of the same length, so it is easy to "slip" between them just by shifting the location of the accents. This interpretational switch has been exploited, for example, by Leonard Bernstein, in the song "America":

Compound metre divided into three parts could theoretically be transcribed into musically equivalent simple metre using triplets. Likewise, simple metre can be shown in compound through duples. In practice, however, this is rarely done because it disrupts conducting patterns when the tempo changes. When conducting in 6

8, conductors typically provide two beats per bar; however, all six beats may be performed when the tempo is very slow.

Compound time is associated with "lilting" and dancelike qualities. Folk dances often use compound time. Many Baroque dances are often in compound time: some gigues, the courante, and sometimes the passepied and the siciliana.

Metre in song

The concept of metre in music derives in large part from the poetic metre of song and includes not only the basic rhythm of the foot, pulse-group or figure used but also the rhythmic or formal arrangement of such figures into musical phrases (lines, couplets) and of such phrases into melodies, passages or sections (stanzas, verses) to give what Holst (1963) calls "the time pattern of any song".[19]

Traditional and popular songs may draw heavily upon a limited range of metres, leading to interchangeability of melodies. Early hymnals commonly did not include musical notation but simply texts that could be sung to any tune known by the singers that had a matching metre. For example, The Blind Boys of Alabama rendered the hymn "Amazing Grace" to the setting of The Animals' version of the folk song "The House of the Rising Sun". This is possible because the texts share a popular basic four-line (quatrain) verse-form called ballad metre or, in hymnals, common metre, the four lines having a syllable-count of 8–6–8–6 (Hymns Ancient and Modern Revised), the rhyme-scheme usually following suit: ABAB. There is generally a pause in the melody in a cadence at the end of the shorter lines so that the underlying musical metre is 8–8–8–8 beats, the cadences dividing this musically into two symmetrical "normal" phrases of four bars each.[20]

In some regional music, for example Balkan music (like Bulgarian music, and the Macedonian 3+2+2+3+2 metre), a wealth of irregular or compound metres are used. Other terms for this are "additive metre"[21] and "imperfect time".[22][failed verification]

Metre in dance music

Metre is often essential to any style of dance music, such as the waltz or tango, that has instantly recognizable patterns of beats built upon a characteristic tempo and bar. The Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing defines the tango, for example, as to be danced in 2

4 time at approximately 66 beats per minute. The basic slow step forwards or backwards, lasting for one beat, is called a "slow", so that a full "right–left" step is equal to one 2

4 bar.[24]

But step-figures such as turns, the corte and walk-ins also require "quick" steps of half the duration, each entire figure requiring 3–6 "slow" beats. Such figures may then be "amalgamated" to create a series of movements that may synchronise to an entire musical section or piece. This can be thought of as an equivalent of prosody (see also: prosody (music)).

Metre in classical music

In music of the common practice period (about 1600–1900), there are four different families of time signature in common use:

- Simple duple: two or four beats to a bar, each divided by two, the top number being "2" or "4" (2

4, 2

8, 2

2 ... 4

4, 4

8, 4

2 ...). When there are four beats to a bar, it is alternatively referred to as "quadruple" time. - Simple triple: three beats to a bar, each divided by two, the top number being "3" (3

4, 3

8, 3

2 ...) - Compound duple: two beats to a bar, each divided by three, the top number being "6" (6

8, 6

16, 6

4 ...) Similarly compound quadruple, four beats to a bar, each divided by three, the top number being "12" (12

8, 12

16, 12

4 ...) - Compound triple: three beats to a bar, each divided by three, the top number being "9" (9

8, 9

16, 9

4)

If the beat is divided into two the metre is simple, if divided into three it is compound. If each bar is divided into two it is duple and if into three it is triple. Some people also label quadruple, while some consider it as two duples. Any other division is considered additively, as a bar of five beats may be broken into duple+triple (12123) or triple+duple (12312) depending on accent. However, in some music, especially at faster tempos, it may be treated as one unit of five.

Changing metre

In 20th-century concert music, it became more common to switch metre—the end of Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring (shown below) is an example. This practice is sometimes called mixed metres.

![{ \new PianoStaff << \new Staff \relative c'' { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"violin" \clef treble \tempo 8 = 126 \override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #4 \time 3/16 r16 <d c a fis d>-! r16\fermata | \time 2/16 r <d c a fis d>-! \time 3/16 r <d c a fis d>8-! | r16 <d c a fis d>8-! | \time 2/8 <d c a fis>16-! <e c bes g>->-![ <cis b aes f>-! <c a fis ees>-!] } \new Staff \relative c { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"violin" \clef bass \time 3/16 d,16-! <bes'' ees,>^\f-! r\fermata | \time 2/16 <d,, d,>-! <bes'' ees,>-! | \time 3/16 d16-! <ees cis>8-! | r16 <ees cis>8-! | \time 2/8 d16^\sf-! <ees cis>-!->[ <d c>-! <d c>-!] } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/d/kd0d2idcbjo5l4e03c969218icat3xx/kd0d2idc.png)

A metric modulation is a modulation from one metric unit or metre to another.

The use of asymmetrical rhythms – sometimes called aksak rhythm (the Turkish word for "limping") – also became more common in the 20th century: such metres include quintuple as well as more complex additive metres along the lines of 2+2+3 time, where each bar has two 2-beat units and a 3-beat unit with a stress at the beginning of each unit. Similar metres are often used in Bulgarian folk dances and Indian classical music.

Hypermetre

Hypermetre is large-scale metre (as opposed to smaller-scale metre). Hypermeasures consist of hyperbeats.[25] "Hypermeter is metre, with all its inherent characteristics, at the level where bars act as beats".[26] For example, the four-bar hypermeasures are the prototypical structure for country music, in and against which country songs work.[26] In some styles, two- and four-bar hypermetres are common.[citation needed]

The term was coined, together with "hypermeasures", by Edward T. Cone (1968), who regarded it as applying to a relatively small scale, conceiving of a still larger kind of gestural "rhythm" imparting a sense of "an extended upbeat followed by its downbeat"[27] London (2012) contends that in terms of multiple and simultaneous levels of metrical "entrainment" (evenly spaced temporal events "that we internalize and come to expect", p. 9), there is no in-principle distinction between metre and hypermetre; instead, they are the same phenomenon occurring at different levels.[28]

Lee (1985)[verification needed] and Middleton have described musical metre in terms of deep structure, using generative concepts to show how different metres (4

4, 3

4, etc.) generate many different surface rhythms.[citation needed] For example, the first phrase of The Beatles' "A Hard Day's Night", excluding the syncopation on "night", may be generated from its metre of 4

4:[29]

The syncopation may then be added, moving "night" forward one eighth note, and the first phrase is generated.[citation needed]

Polymetre

With polymetre, the bar sizes differ, but the beat remains constant. Since the beat is the same, the various metres eventually agree. (Four bars of 7

4 = seven bars of 4

4). An example is the second moment, titled "Scherzo polimetrico", of Edmund Rubbra's Second String Quartet (1951), in which a constant triplet texture holds together overlapping bars of 9

8, 12

8, and 21

8, and barlines rarely coincide in all four instruments.[30]

With polyrhythm, the number of beats varies within a fixed bar length. For example, in a 4:3 polyrhythm, one part plays 4

4 while the other plays 3

4, but the 3

4 beats are stretched so that three beats of 3

4 are played in the same time as four beats of 4

4.[citation needed] More generally, sometimes rhythms are combined in a way that is neither tactus nor bar preserving—the beat differs and the bar size also differs. See Polytempi.[citation needed]

Research into the perception of polymetre shows that listeners often either extract a composite pattern that is fitted to a metric framework, or focus on one rhythmic stream while treating others as "noise". This is consistent with the Gestalt psychology tenet that "the figure–ground dichotomy is fundamental to all perception".[31][verification needed][32] In the music, the two metres will meet each other after a specific number of beats. For example, a 3

4 metre and 4

4 metre will meet after 12 beats.

In "Toads of the Short Forest" (from the album Weasels Ripped My Flesh), composer Frank Zappa explains: "At this very moment on stage we have drummer A playing in 7

8, drummer B playing in 3

4, the bass playing in 3

4, the organ playing in 5

8, the tambourine playing in 3

4,[clarification needed] and the alto sax blowing his nose".[33] "Touch And Go", a hit single by The Cars, has polymetric verses, with the drums and bass playing in 5

4, while the guitar, synthesizer, and vocals are in 4

4 (the choruses are entirely in 4

4).[34] Magma uses extensively 7

8 on 2

4 (e.g. Mëkanïk Dëstruktïẁ Kömmandöh) and some other combinations. King Crimson's albums of the eighties have several songs that use polymetre of various combinations.[citation needed]

Polymetres are a defining characteristic of the music of Meshuggah, whose compositions often feature unconventionally timed rhythm figures cycling over a 4

4 base.[35]

Examples

4 with 4 4 |

4 with 3 4 |

4 with 4 4 |

4 with 3 8 |

4 with 5 8 |

4 with 7 8 |

8 at tempo of 90 bpm |

8 at tempo of 90 bpm |

8 at tempo of 90 bpm |

4 at a tempo of 60 bpm |

4 at a tempo of 60 bpm |

4 at a tempo of 60 bpm |

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Scholes 1977.

- ^ a b Latham 2002b.

- ^ Hoppin 1978, 221.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2015.

- ^ Cooper & Meyer 1960, p. 3.

- ^ a b MacPherson 1930, 3.

- ^ Holst 1963, 17.

- ^ London 2004, 4.

- ^ Yeston 1976, 50–52.

- ^ Lester 1986, 77.

- ^ Benward and Saker 2003, 9.

- ^ a b MacPherson 1930, 5.

- ^ Cooper & Meyer 1960, p. [page needed].

- ^ Cooper 1973, 30.

- ^ Karpinski 2000, 19.

- ^ Forney and Machlis 2007, ?.

- ^ a b Wittlich 1975, ch. 3.

- ^ Latham 2002a.

- ^ Holst 1963, 18.

- ^ MacPherson 1930, 14.

- ^ London 2001, §I.8.

- ^ Read 1964, 147.

- ^ Scruton 1997.

- ^ Anon. 1983, p. [page needed].

- ^ Stein 2005, 329.

- ^ a b Neal 2000, 115.

- ^ Berry and Van Solkema 2013, §5(vi).

- ^ London 2012, 25.

- ^ Middleton 1990, 211.

- ^ Rubbra 1953, 41.

- ^ Boring 1942, 253.

- ^ London 2004, 49–50.

- ^ Mothers of Invention 1970.

- ^ Cars 1981, 15.

- ^ Pieslak 2007.

Sources

- Anon. (1983). Ballroom Dancing. Teach Yourself. Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-22517-2.

- Benward, Bruce, and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. 1, seventh edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-294262-2.

- Berry, David Carson, and Sherman Van Solkema (2013). "Theory". The Grove Dictionary of American Music, second edition, edited by Charles Hiroshi Garrett. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531428-1.

- Boring, Edwin G. (1942). Sensation and Perception in the History of Experimental Psychology. New York: Appleton-Century.

- Cars, The (1981). Panorama (songbook). New York: Warner Bros. Publications.

- Cone, Edward T. (1968). Musical Form and Musical Performance. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-39309767-2.

- Cooper, Grosvenor; Meyer, Leonard B. (1960). The Rhythmic Structure of Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-11521-6. OCLC 1139523.

- Cooper, Paul (1973). Perspectives in Music Theory: An Historical-Analytical Approach. New York: Dodd, Mead. ISBN 0-396-06752-2.

- Forney, Kristine, and Joseph Machlis (2007). The Enjoyment of Music: An Introduction to Perceptive Listening, tenth edition. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-92885-3 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-393-17410-6 (text with DVD); ISBN 978-0-393-92888-4 (pbk.); ISBN 978-0-393-10757-9 (DVD)

- Holst, Imogen (1963). The ABC of Music: A Short Practical Guide to the Basic Essentials of Rudiments, Harmony, and Form'. Benjamin Britten (foreword). London & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-317103-1.

- Hoppin, Richard H. 1978. Medieval Music. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-09090-6.

- Karpinski, Gary S. (2000). Aural Skills Acquisition: The Development of Listening, Reading, and Performing Skills in College-Level Musicians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511785-9.

- Krebs, Harald (2005). "Hypermeter and Hypermetric Irregularity in the Songs of Josephine Lang.". In Deborah Stein (ed.). Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517010-5.

- Latham, Alison (2002a). "Compound Time [Compound Metre]". In Alison Latham (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866212-2.

- Latham, Alison (2002b). "Metre". In Alison Latham (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866212-2.

- Lee, C. S. (1985). "The Rhythmic Interpretation of Simple Musical Sequences: Towards a Perceptual Model". In Peter Howell; Ian Cross; Robert West (eds.). Musical Structure and Cognition. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12357170-0.

- Lester, Joel (1986). The Rhythms of Tonal Music. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-1282-4.

- London, Justin (2001). "Rhythm". In Stanley Sadie; John Tyrrell (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan.

- London, Justin (2004). Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter (first ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516081-9.

- London, Justin (2012). Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter (second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974437-4.

- MacPherson, Stewart (1930). Form in Music. London: Joseph Williams Ltd.

- Merriam-Webster (2015). "Measure". Dictionary. New York.

- Middleton, Richard (1990). Studying Popular Music. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-33515276-6.

- Mothers of Invention, The (1970), Weasels Ripped My Flesh (LP), Bizarre Records / Reprise Records, MS 2028 at Discogs (list of releases)

- Neal, Jocelyn (2000). "Songwriter's Signature, Artist's Imprint: The Metric Structure of a Country Song". In Wolfe, Charles K.; Akenson, James E. (eds.). Country Music Annual 2000. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0989-2.

- Pieslak, Jonathan (2007). "Re-casting Metal: Rhythm and Meter in the Music of Meshuggah". Music Theory Spectrum. 29 (2): 219–45. doi:10.1525/mts.2007.29.2.219.

- Read, Gardner (1964). Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Rubbra, Edmund (1953). "String Quartet No. 2 in E-flat, Op. 73: An Analytical Note by the Composer." The Music Review 14:36–44.

- Scholes, Percy (1977). John Owen Ward (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Music. 6th corrected reprint of the 10th ed. (1970), revised and reset. London and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-311306-6., chapters "Metre" and "Rhythm"

- Scruton, Roger (1997). The Aesthetics of Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 25ex2.6. ISBN 0-19-816638-9.

- Wittlich, Gary E., ed. (1975). Aspects of Twentieth-century Music. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-049346-5.

- Yeston, Maury (1976). The Stratification of Musical Rhythm. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01884-3.

Further reading

- Anon. (1999). "Polymeter." Baker's Student Encyclopedia of Music, 3 vols., ed. Laura Kuhn. New York: Schirmer-Thomson Gale; London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-02-865315-7. Online version 2006: Archived 27 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Anon. [2001]. "Polyrhythm". Grove Music Online. (Accessed 4 April 2009)

- Hindemith, Paul (1974). Elementary Training for Musicians, second edition (rev. 1949). Mainz, London, and New York: Schott. ISBN 0-901938-16-5.

- Honing, Henkjan (2002). "Structure and Interpretation of Rhythm and Timing." Tijdschrift voor Muziektheorie 7(3):227–232. (pdf)

- Larson, Steve (2006). "Rhythmic Displacement in the Music of Bill Evans". In Structure and Meaning in Tonal Music: Festschrift in Honor of Carl Schachter, edited by L. Poundie Burstein and David Gagné, 103–122. Harmonologia Series, no. 12. Hillsdale, New York: Pendragon Press. ISBN 1-57647-112-8.

- Waters, Keith (1996). "Blurring the Barline: Metric Displacement in the Piano Solos of Herbie Hancock". Annual Review of Jazz Studies 8:19–37.

![\new Staff <<

\new voice \relative c' {

\clef percussion

\numericTimeSignature

\time 3/4

\set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 4 = 100

\stemDown \repeat volta 2 { g4 d' d }

}

\new voice \relative c'' {

\override NoteHead.style = #'cross

\stemUp \repeat volta 2 { a8[ a] a[ a] a[ a] }

}

>>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/h/i/hi5b5unz1padlgy7b5jgghe9ncoqm7c/hi5b5unz.png)

![\new Staff <<

\new voice \relative c' {

\clef percussion

\numericTimeSignature

\time 3/4

\set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 4 = 100

\stemDown \repeat volta 2 { g4 d' d }

}

\new voice \relative c'' {

\override NoteHead.style = #'cross

\stemUp \repeat volta 2 { a8[ a] a[ a] a[ a] }

}

>>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/0/q09k3q6mf4rqihq957lfeqnncvfjznl/q09k3q6m.png)