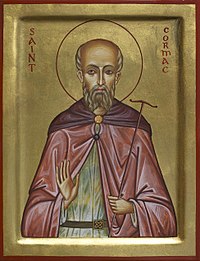

Cormac mac Cuilennáin (died 13 September 908) was an Irish bishop and the king of Munster from 902 until his death at the Battle of Bellaghmoon. He was killed in Leinster.

Cormac was regarded as a saintly figure after his death, and his shrine at Castledermot, County Kildare, was said to be the site of miracles. He was reputed to be a great scholar and is credited with the authorship of the Sanas Cormaic (Cormac's Glossary) and the now-lost Psalter of Cashel, among other works. The reliability of some of the traditions concerning Cormac is doubtful. His feast day is September 14.[2]

Background

The Ireland of Cormac's time was divided into small kingdoms or túatha, perhaps 150 in all, on average around 500 square kilometres in area, with a population of some 3000 each. In theory, but not in practice, each tuath had its own king, bishop, and court. Variations in size and power were very considerable. Groups of tuatha were dominated by one of their number, whose king was their collective ruler. Above these stood the five great provincial kingships whose names survive in the provinces of Ireland: Connacht, Leinster, Ulster, Meath, and Cormac's Munster. To these can be added the kings of the northern and southern Uí Néill. These last provided were the High Kings of Ireland, kings whose authority was an increasingly obvious political fact in Ireland of the 8th and 9th centuries.[3] In Cormac's time the High Kingship was held by Flann Sinna of the Clann Cholmáin branch of the southern Uí Néill. In addition to these native Irish kings, Ireland had also seen Scandinavian and Norse-Gael kings establish themselves along the coasts during the Viking Age. The destruction of Viking settlements on the northern coasts by Flann's predecessor Áed Findliath, followed by much internal dissension, had weakened the Vikings, who were expelled from Dublin by Flann's allies in the year that Cormac became the king of Munster.[4]

Cormac belonged to a minor branch of the Eóganachta clan which dominated Munster in the 8th and 9th centuries. According to genealogies, he was a member of the Eóganacht Chaisil, the Cashel branch of the clan. This kin group was important, but Cormac came from a very minor branch. He was considered to be an eleventh-generation descendant of Óengus mac Nad Froích and none of his ancestors since Óengus were counted as kings of Cashel. Cormac, as well as other 9th century kings of Munster who were bishops and abbots, was probably a compromise candidate.[5]

The Annals of the Four Masters, a 17th-century compilation of annals based on earlier works, but including much of uncertain reliability, state that Cormac was tutored by Snedgus of Dísert Díarmata (now Castledermot).[6] Some later accounts claim that Cormac had been married or betrothed to Gormlaith, daughter of Flann Sinna, the High King of Ireland, but instead took vows of celibacy. Paul Russell. writing in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography suggests these are later fictions and historian Francis John Byrne saw an echo of earlier tales of the sovereignty goddess in them.[7] Although there is no doubt that Cormac was a bishop before and while he was king of Munster, it is not clear which see Cormac held. Some writers have suggested that he should be linked with Emly rather than Cashel.

King and bishop

Cormac was chosen as king of Munster following the death of Finguine Cenn nGécan, who is said by the Annals of Ulster to have been "deceitfully killed by his associates" and by the Annals of Innisfallen to have been killed by the Cenél Conaill Chaisil, a branch of the Cashel Eóganachta.[8] The Annals of Innisfallen note the beginning of Cormac's reign and call him a "noble bishop and celibate".[9]

Cormac may have attempted to restore the authority of the kings of Munster over neighbouring Leinster and perhaps aspired to be chief king in Ireland. The surviving record, written largely from a northern and pro-Uí Néill perspective, presents a misleading picture and understates the power and pretensions of the Eóganachta.[10] The southern Annals of Innisfallen report campaigns in 907 by Cormac in Connacht and Mide, where Flann Sinna was defeated at Mag Lena, and record a fleet operating on the River Shannon on his orders which captured Clonmacnoise.[11]

Cath Belach Mugna

In 908, Cormac and Flaithbertach mac Inmainén, Cormac's chief councillor and abbot of Scattery Island, collected an army to campaign against their eastern neighbours, Leinster, whose king Cerball mac Muirecáin was Flann Sinna's son-in-law and staunch ally. The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, a source compiled in the 11th century for Donnchad mac Gilla Pátraic, king of Osraige, and king of Leinster, contain a long account of these events, perhaps written within living memory.[12]

After the army of Munster had gathered, Flaithbertach mac Inmainén's horse stumbled and threw him to the ground while riding through the camp; it was taken to be a very bad omen. Many of the Munstermen were unwilling to fight, and news reached Cerball mac Muirecáin, who proposed a negotiated settlement. The Leinstermen would pay tribute, and give hostages, but the hostages would be given to Móenachem abbot of Dísert Díarmata, rather than to the Munstermen. Cormac was willing to accept this settlement, but Flaithbertach—Byrne notes that later traditions make Flaithbertach Cormac's evil genius[13]— was not and persuaded Cormac to fight, in spite of the king's conviction that he would be killed.[14]

This, and the news that Flann and the Uí Néill had come to Cerball's aid, led to desertions from Cormac's army, but he continued to march to Leinster and met Cerball and Flann at Bellach Mugna (Bellaghmoon, in the south of modern County Kildare). The Fragmentary Annals say that "the men of Munster came to the battle weak and in disorder" and they quickly broke and fled the field. Many were killed; Cormac was among them after he broke his neck from falling off his horse. Flaithbertach was captured.[15]

Cormac was beheaded and his head was taken to Flann Sinna. The Fragmentary Annals say:

"That is indeed evil," said Flann to them, and it was not thanks that he gave them. "It was an evil deed," he said, "to cut off the holy bishop's head; I shall honour it, and not crush it." Flann took the head in his hands, and kissed it, and he carried the consecrated head and the true martyr around him three times.[16]

Following Cormac's death, Munster was seemingly without a king for some years until Flaithbertach mac Inmainén was chosen, apparently another compromise candidate.[17]

Saint and scholar

Cormac was reckoned to be a saint in the 11th century by contemporary evidence. The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland state that Cormac was buried at Dísert Díarmata where he was honoured, and add that "Cormac's body ... produces omens and miracles".[19]

The Fragmentary Annals are equally glowing in their praise of Cormac's scholarship and piety: "A scholar in Irish and in Latin, the wholly pious and pure chief bishop, miraculous in chastity and in prayer, a sage in government, in all wisdom, knowledge and science, a sage of poetry and learning, chief of charity and every virtue; a wise man in teaching, high king of the two provinces of all Munster in his time."[20]

A variety of works have been associated with Cormac, such as the Sanas Cormaic, a glossary of difficult words in Irish in the style of Isidore of Seville, which bears his name. While the core of the document dates from around Cormac's time, and may in some way be linked to him, it is uncertain if he was the compiler of even the original list. The lost Psalter of Cashel and the Lebor na Cert—the Book of Rights—is also linked to Cormac. The works that survive today are probably from the time of Muirchertach Ua Briain.[21] Liam Breatnach also attributes Amra Senáin to Cormac.[22]

Genealogy

Cormac mac Cuilennáin mac Selbach mac Ailgile mac Eochaid mac Colmán mac Dúnchad mac Dub Indrecht mac Furudrán mac Eochaid mac Bressal mac Óengus mac Nad Froich mac Corc.[23]

See also

Notes

- ^ Bowe, Nicola Gordon; Caron, David; Wynne, Michael (1988). Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. p. 46. ISBN 0-7165-2413-9.

- ^ "St. Cormac of Cashel, King & Bishop; 14 September". Celtic Saints. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021.

- ^ Byrne, Irish Kings, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, pp. 254–256.

- ^ Byrne, Irish Kings, pp. 214 & 292.

- ^ Russell, "Cormac"; Annals of the Four Masters, AFM 885.11.

- ^ Russell, "Cormac"; Byrne, Irish Kings, p. 164.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, AU 902.1; Annals of Innisfallen, AI 902.1.

- ^ Annals of Innisfallen, AI 901.3.

- ^ Hughes, Early Christian Ireland, pp.136–137; Byrne, Irish Kings, p. 203.

- ^ Russell, "Cormac"; Annals of Innisfallen, AI 907.1, AI 907.3 & AI 907.4.

- ^ Wiley, "Cath Belaig Mugna".

- ^ Byrne, Irish Kings, p. 214

- ^ Wiley, "Cath Belaig Mugna"; Russell "Cormac"; Fragmentary Annals, FA 423.

- ^ Wiley, "Cath Belaig Mugna"; Russell "Cormac"; Fragmentary Annals, FA 423; Annals of Ulster, AU 908.3; Annals of Innisfallen, AI 908.2; Annals of the Four Masters, AFM 903.7.

- ^ Fragmentary Annals, FA 423; Byrne, Irish Kings, pp. 214–215, notes that martyrdom is the usual term used of the death of a cleric by violence.

- ^ Byrne, Irish Kings, p. 204.

- ^ Crawford, Irish Carved Ornament, reproduces the panel, see illustration no. 150 and comments on pp. 73–74.

- ^ Fragmentary Annals, FA 423; Dumville, "Félire Óengusso", p. 36.

- ^ Fragmentary Annals, FA 423.

- ^ Russell, "Cormac"; Byrne, Irish Kings, p. 192.

- ^ Breatnach, Liam, “An edition of Amra Senáin”, in: Ó Corráin, Donnchadh, Liam Breatnach, and Kim R. McCone (eds.), Sages, saints and storytellers: Celtic studies in honour of Professor James Carney, Maynooth Monographs 2, Maynooth: An Sagart, 1989. 7–31.

- ^ Byrne, Irish Kings, p. 292.

References

- Seán Mac Airt, ed. (1944). The Annals of Inisfallen (MS. Rawlinson B. 503). Translated by Mac Airt. Dublin: DIAS. Edition and translation available from CELT.

- Annals of the Four Masters, CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, 2002, retrieved 16 December 2007

- Seán Mac Airt; Gearóid Mac Niocaill, eds. (1983). The Annals of Ulster (to AD 1131). Translated by Mac Airt; Mac Niocaill. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- Byrne, Francis John (1973), Irish Kings and High-Kings, London: Batsford, ISBN 0-7134-5882-8

- Crawford, H. S. (1980), Irish Carved Ornament from Monuments of the Christian Period (reprinted ed.), Dublin: Mercier Press, ISBN 0-85342-632-5

- Dumville, David (2002), "Félire Óengusso: Problems of Dating a Monument of Old Irish" (PDF), Éigse: A Journal of Irish Studies, 33: 19–48, ISSN 0013-2608, retrieved 29 March 2008

- Hughes, Kathleen (1972), Early Christian Ireland: Introduction to the Sources, The Sources of History, London: Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 0-340-16145-0

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí (1995), Early Medieval Ireland: 400–1200, London: Longman, ISBN 0-582-01565-0

- Radner, Joan N., ed. (2004) [1975], Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, retrieved 10 February 2007

- Russell, Paul (2004). "Cormac mac Cuilennáin (d. 908)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6319. Retrieved 22 March 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Wiley, Dan M. (2005), "Cath Belaig Mugna", The Cycles of the Kings, archived from the original on 7 May 2008, retrieved 21 March 2008

- Ní Mhaonaigh, Máire, Cormac mac Cuilennáin: king, bishop, and 'wondrous sage, Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 58 (2011): 108–128.