| Flann Sinna | |

|---|---|

| High King of Ireland | |

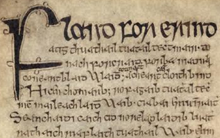

Opening lines of Máel Mura Othna's poem Flann for Érinn (Flann over Ireland), from the Great Book of Lecan (RIA MS 23 P 2), 296v | |

| Reign | 879–916 |

| Predecessor | Áed Findliath |

| Successor | Niall Glúndub |

| Born | 847 |

| Died | 25 May 916 (aged 68–69) Lough Ennel, Kingdom of Meath |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue |

|

| Father | Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid |

| Mother | Land ingen Dúngaile |

Flann mac Máel Sechnaill (847 – 25 May 916), better known as Flann Sinna (lit. 'Flann of the Shannon'; Irish: Flann na Sionainne), was the son of Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid of Clann Cholmáin, the leading branch of the Southern Uí Néill. He was King of Mide from 877 onwards and a High King of Ireland. His mother Land ingen Dúngaile was a sister of Cerball mac Dúnlainge, King of Osraige.

Flann was chosen as the High King of Ireland, also known as King of Tara, following the death of his first cousin and stepfather Áed Findliath on 20 November 879. Flann's reign followed the usual pattern of Irish High Kings, beginning by levying hostages and tribute from Leinster and then to wars with Munster, Ulster, and Connacht. Flann was more successful than most kings of Ireland. However, rather than the military and diplomatic successes of his reign, it is his propaganda statements, in the form of monumental high crosses naming him and his father as kings of Ireland, that are exceptional.

Flann may have had the intention of abandoning the traditional succession to the kingship of Tara, whereby the northern and southern branches of the Uí Néill held the kingship alternately, but such plans were thwarted when his favoured son Óengus was killed by his son-in-law and eventual successor Niall Glúndub, son of Áed Findliath, on 7 February 915. Flann's other sons revolted and his authority collapsed.

Ireland in the First Viking Age

The Viking Age in Ireland began in 795 with attacks on monasteries on the islands of Rathlin, Inishmurray, and Inishbofin. In the following twenty years, raids by Vikings—called "Foreigners" or "Gentiles" in Irish sources—were small in scale, infrequent and largely limited to the coasts. The Annals of Ulster record raids in Ireland in only five of the first twenty years of the 9th century. In the 820s, there are records of larger raids in Ulster and Leinster. The range, size, and frequency of attacks increased in the 830s. In 837, Viking fleets operated on the rivers Boyne and Liffey in central Ireland, and in 839 a fleet was based on Lough Neagh in the north-east.[1]

The records indicate that the first permanent Viking bases were established in 841, near Dublin and Annagassan.[2] Other fortified settlements were established in the following decades at Wexford, Waterford, Limerick, and Cork.[3] It is in this period that the leaders of the Irish-based Scandinavians are recorded by name. Turgesius, who is made the conqueror of Ireland by Giraldus Cambrensis and a son of Harald Fairhair by Scandinavian sagas, is one of these. He was captured, and drowned in Lough Owel, by Máel Sechnaill in 845. Máel Sechnaill was reported to have killed 700 Foreigners in 848, and the King of Munster, Ólchobar mac Cináeda, killed 200 more, including an earl named Tomrair, the "heir designate of the King of Laithlind".[4]

In 849, a new force appeared, the "Dark Foreigners". Possibly Danes, their activities were directed against the "Foreigners" already in Ireland. A major naval battle fought in Carlingford Lough in 853 produced a victory for the newcomers. In the same year, there arrived another force, the "Fair Foreigners", led by Amlaíb, "son of the king of Laithlind", and Ímar. From the 840s onwards, the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland and the Irish annals recount frequent alliances between the "Foreigners" and Irish kings, especially after the appearance of Amlaíb and Ímar as rulers of Dublin.[5]

The later 860s saw a reduction of activity by the Foreigners—although the Annals indignantly report that they plundered the ancient burial mounds at Newgrange, Knowth, and Dowth in 863—with the Dublin forces active in Pictland and in the six months' siege of Dumbarton Rock. Áed Findliath took advantage of these absences to destroy the Viking fortresses in the north of Ireland. Amlaíb left Ireland for good in 871 and Ímar died in 873. With their disappearance, there were frequent changes of leadership among the Foreigners and a great deal of internecine conflict is reported for the following decades.[6]

Máel Sechnaill mac Maíl Ruanaid

The making of a kingship of Ireland, as kings from Flann to Brian Bóruma, Muircheartach Ua Briain and Tairrdelbach mac Ruaidri Ua Conchobair (Turlough O'Connor) exercised, may owe as much to the threat raised by Feidlimid mac Crimthainn, of the Eóganachta of Cashel (Eóganachta Chaisil), King of Munster, as to the Viking raids on Ireland.[8]

Feidlimid's Munstermen ravaged the length and breadth of Ireland, as far north as the Cenél nEógain heartland of Inishowen. Drawing on the support of the clergy of Cashel as well as his own military might, Feidlimid is said by Munster sources to have made himself King of Tara. Although he was defeated in 841 in battle with Niall Caille of the Cenél nEógain, the High King according to some, Feidlimid's achievements were exceptional. Not since Congal Cáech of the Dál nAraidi, King of Ulaid in the early 7th century, had any king but an Uí Néill one been reckoned King of Tara in any account.[9]

On Niall Caille's death in 846, the kingship of Tara passed to Flann Sinna's father Máel Sechnaill. Feidlimid died in the following year, and Máel Sechnaill proceeded to expand his power by war and diplomacy. What is noteworthy about Máel Sechnaill's expansionism, normal for Irish kings, is not that it happened, but the language used to describe it. The Annals of Ulster refer to Máel Sechnaill's armies, not as the "men of Mide", or of the Clann Cholmáin, but as the "men of Ireland" (an expedition co feraib Érenn is recorded in 858).[10] Alongside this innovation, the terms goídil (gael), gaill (foreigners) and gallgoídil (Norse-Gaels) become more common, along with phrases such as the Gaíll Érenn (the foreigners of Ireland, used to refer to the Norse-Gaels of the Irish coasts).[11]

On his death in 862, Máel Sechnaill's obituary titled him "King of all Ireland" (Old Irish: rí hÉrenn uile).[12]

Áed Finnliath

On Máel Sechnaill's death, the Uí Néill kingship passed back to the northern branch, represented by Áed Findliath, son of Niall Caille. Áed began his reign by marrying Máel Sechnaill's widow, Flann's mother, Land (d. 890), daughter of Dúngal mac Cerbaill, king of Osraige. Áed had some notable successes against the Vikings, and was active against the Laigin. However, his kingship was not accepted even among the southern Uí Néill. The historical records indicate that six times during his reign, or one year in three, the great Fair of Tailtiu was not held, "although there was no just and worthy reason for this". When Áed died in 879, the kingship returned to the southern branch, represented by Flann Sinna.[13]

During the reign of his stepfather, Flann enters the historical record. In 877, the Annals of Ulster record that "Donnchad son of Aedacán son of Conchobor, was deceitfully killed by Flann son of Máel Sechnaill". Donnchad, the reigning King of Mide and head of the southern Uí Néill, was Flann's second cousin.[14] Flann's marriage to Áed Findliath's daughter Eithne may have taken place before he seized power, or soon afterwards.[15]

Flann over Ireland

| 847 or 848: birth of Flann Sinna |

| 862: death of Máel Sechnaill |

| 877: Flann kills Donnchad mac Eochocain, becomes King of Mide |

| 879: Áed Findliath dies |

| 882: Flann attacks Armagh |

| 888: Flann defeated by the Foreigners at the Battle of the Pilgrim |

| 889: Domnall son of Áed Findliath raids Mide |

| 892: many Foreigners leave Dublin |

| c. 900: Cathal mac Conchobair, King of Connacht, accepts Flann's authority |

| 901: the killing of Flann's son Máel Ruanaid |

| 902: Foreigners leave, or are driven out, of Dublin |

| 904: quarrel between Flann and his son Donnchad |

| 905: Flann attacks Osraige |

| 906: Flann raids Munster, the Munsterman retaliate |

| 908: Flann and his allies defeat the Munstermen and kill their king, Cormac mac Cuilennáin |

| 909: oratory at Clonmacnoise rebuilt in stone on Flann's orders |

| 910: Flann attacks the kingdom of Bréifne |

| 913 and 914: Flann and his son Donnchad raid south Brega, burning many churches |

| 914: battle between Niall Glúndub and Óengus, son of Flann; Óengus mortally wounded |

| 915: Flann's sons Donnchad and Conchobar rebel; Flann names Niall Glúndub as his heir |

| 916: death of Flann |

Flann's reign began with a demand for hostages from the kings of Leinster. In 882, he led an army of Irishmen and "Foreigners" into the north, attacking Armagh.[16] Unlike the later poetic accounts which made the Gaels and the "Foreigners" bitterest enemies, and recast events as a struggle between natives and incomers, Irish kings generally had no qualms about allying themselves with the "Foreigners" when convenient.[17] It is likely that one of Flann's sisters was married to a Norse or Norse-Gael leader. Gerald of Wales offers a typically inventive account of how this marriage came about in his Topographia Hibernica. Gerald claimed that Máel Sechnaill had granted his daughter to the Viking chieftain called Turgesius, and he had sent fifteen beardless young men, disguised as the bride's handmaidens, to kill the chieftain and his closest associates.[18]

The Annals of Ulster report that Flann was defeated in 887 by the "Foreigners" at the Battle of the Pilgrim. Among the dead on Flann's side were Áed mac Conchobair of the Uí Briúin Ai, King of Connacht, Lergus mac Cruinnén, Bishop of Kildare, and Donnchad, Abbot of Kildare. Irish clergymen commonly appear among the named dead in battles of the Early Christian and Viking periods. In that year the Fair of Tailtiu was not held, a sign that Flann's authority was not unchallenged. Flann's defeat at the hands of the "Foreigners" was overshadowed by the signs of dissension among their leaders. That same year, the Annals of Ulster note that "Sigfrith son of Ímar, king of the Norsemen, was deceitfully killed by his kinsman".[19] For the following year, the Annals report an "expedition by Domnall son of Áed [Finnliath] with the men of the north of Ireland against the southern Uí Néill", and again in 888, the Fair of Tailtiu was reportedly not held.[20]

In 892, events in England may have had an impact in Ireland, leading to the fall of Dublin (Áth Cliath) to the Irish. The Annals, following a report of the defeat of the Vikings by the Saxons—Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, who was Flann's contemporary—announce "great dissension among the "Foreigners" of Áth Cliath, and they became dispersed, one section of them following Ímar's son, and the other Sigfrith the jarl".[21] Amlaíb son of Ímar was killed in 897, and for 901, the Annals say that the "heathens were driven from Ireland" by the Leinstermen, led by Flann's son-in-law Cerball, and the "men of Brega", led by Máel Finnia son of Flannacán.[22]

In 901, Flann's son Máel Ruanaid, described as "heir designate of Ireland", was killed, probably burnt in a hall along with other notables, by the Luigni of Connaught. In 904, Flann broke into the Abbey of Kells in order to seize his son Donnchad, who had taken refuge there, and beheaded many of Donnchad's associates. By this point in time, Flann had been king of Ireland in style for a quarter century.

Flann undertook an expedition against his cousin Cellach mac Cerbaill, King of Osraige, in 905, after Cellach had succeeded his brother Diarmait earlier in the year. In the following year, 906, Flann raided into Munster and ravaged much of the land there. Cormac mac Cuilennáin of the Eóganachta of Cashel, King of Munster, with his "evil genius" and later successor Flaithbertach mac Inmainén by his side, raided Connaught and Leinster in retaliation and, according to some annals, defeated Flann at Mag Lena. A Munster fleet ravaged the coasts that same year.

Neither spear nor sword will kill him

| 49: He will take the lordship of Tara, pleasant it will be which will be over the plain of Brega, without plunder, without conflict, without battle, without swift slaughter, without death reproach. |

| 50: Twenty-five years, truly, will be the time of the high king; Tara of pleasant Brega will be full, there will be honour over every church. |

| 51: Neither spear nor sword will kill him, he will not fall by weapon-points in his going, in Lough Ennel he will die, after him it will be a noble fame. |

| The Prophecy of Berchán, an 11th-century verse history of Scots and Irish kings.[23] |

On 13 September 908, Flann, aided by his son-in-law Cerball mac Muirecáin, and Cathal mac Conchobair, King of Connacht, fought against the Munstermen, again led by Cormac and Flaithbertach, at the Battle of Bellaghmoon (near Castledermot, County Kildare). The Fragmentary Annals report that many of the men of Munster had not wished to set out on the expedition. This was because Flaithbertach had fallen from his horse at the muster, an event which was taken to be an ill-omen. Flann and his allies subsequently defeated the Munstermen. Cormac, along with Cellach mac Cerbaill of Osraige and many other notables, was killed.[24]

In 910, now without the aid of Cerball, who had died of sickness, Flann defeated the men of Bréifne. In 913 and 914, first Donnchad son of Flann, and then Flann himself, ravaged the lands of south Brega and southern Connaught. In the 914 campaign, the Annals of Ulster report that "many churches were profaned by [Flann]". In December of 914, a battle was fought between Niall Glúndub and Óengus, son of Flann. Óengus died of wounds on 7 February 915, the second of Flann's designated heirs to die in his lifetime.[25]

Later in 915, his sons Donnchad and Conchobar rebelled against Flann, and it was only with the aid of Niall Glundúb that Flann's sons were forced back into obedience. Niall Glúndub also compelled a truce between Flann and Fogartach mac Tolairg, king of Brega. Niall may also have been acknowledged as Flann's heir at this time. Flann did not long survive, dying near Mullingar, County Westmeath, according to the Prophecy of Berchán, on 25 May 916, after a reign of 36 years, 6 months, and 5 days.[26]

Flann was followed as head of Clann Cholmáin and king of Mide by his son Conchobar, and as king of Tara by Niall Glúndub.

Family

Flann Sinna was known to have been married to at least three different women, and his recorded children numbered seven sons and three daughters.

His marriage to Gormlaith ingen Flann mac Conaing, daughter of the King of Brega, a key ally of his stepfather, was probably the first. Known children of this marriage are Donnchad Donn, later King of Mide and of Tara, and Gormlaith.[27]

Flann's daughter Gormflaith ingen Flann Sinna became the subject of later literary accounts, which depicted her as a tragic figure. She was married first to Cormac mac Cuilennáin of the Eóganachta, who had taken vows of celibacy as a bishop. On Cormac's death in battle in 908, fighting against her father, she was married to Cerball mac Muirecáin of the Uí Dúnlainge, who supposedly abused her. Cerball was a key ally of Gormflaith's father. After Cerball's death in 909 Gormflaith married her stepbrother Niall Glúndub, who died in 919. The Annals of Clonmacnoise have her wandering Ireland after Niall's death, forsaken by her kin, and reduced to begging from door to door, although this is thought to be a later invention rather than a tradition with a basis in fact.[28]

The second of Flann's known marriages was his union with Eithne, daughter of Áed Findliath, dated circa 877. Flann and Eithne's son Máel Ruanaid was killed in 901. Eithne was also married to Flannácan, King of Brega, by whom she had a son named Máel Mithig, although whether this preceded her marriage to Flann is unclear. It is likely that Flann divorced Eithne in order to follow the tradition of marrying his predecessor's widow, Eithne's stepmother. Eithne died as a nun in 917.[29]

His third wife, Máel Muire, who died in 913, was the daughter of the King of the Picts, Cináed mac Ailpín. She was the mother of Flann's son, Domnall (King of Mide 919–921; killed by his half-brother Donnchad Donn in 921), and his daughter, Lígach (died 923), wife of the Síl nÁedo Sláine king of Brega, Máel Mithig mac Flannacáin (died 919).[27]

The mothers of Flann Sinna's sons Óengus (died 915), Conchobar (king of Mide 916–919; died in battle against the "Foreigners" alongside his brother-in-law Niall Glúndub), Áed (blinded on Donnchad Donn's orders in 919), and Cerball are unknown, and likewise his daughter Muirgel (died 928), who was probably married to a Norse or Norse-Gael king.[27]

Assessment

The alternating succession of the northern and southern Uí Néill to the kingship of Tara would finally break down in the time of Brian Boru. It was already under strain before Flann Sinna's lifetime. Two branches of the Uí Néill—the northern Cenél Conaill and the southern Síl nÁedo Sláine— had already been excluded from the succession by the Cenél nEógain and Clann Cholmáin. Many other branches of the Uí Néill had never shared in the kingship.

When Flann's son Máel Ruanaid was killed in 901, the obituary in the Annals of Ulster states: "Máel Ruanaid son of Flann son of Máel Sechnaill, heir designate of Ireland, was killed by the Luigne".[30] The Annals of Ulster are derived from the Chronicle of Ireland, kept at Clonmacnoise, Flann's own monastery, and perhaps compiled in his lifetime.[31]

The description of Máel Ruanaid as "heir designate of Ireland" suggests to some that Flann planned to keep the kingship in his family, excluding the Cenél nEógain as the Cenél Conaill and Síl nÁedo Sláine had previously been excluded. The evident lack of filial loyalty among Flann's sons, Donnchad Donn being twice in rebellion against his father, may have prevented any such plans from coming to fruition. However, Óengus is called "heir designate of Temair [Tara]" in the notice of his death in 915.[32]

Benjamin Hudson suggested that it was only the vigorous campaigning by Niall Glúndub in Ulster and Connacht from 913 to 915, along with Óengus's fortuitous death, that led to Niall being named Flann's heir.[33] Alex Woolf suggested that Flann had not only attempted to monopolise the succession within his family, but had come close to instituting a national kingship in Ireland comparable to that created by his contemporaries Alfred the Great and Edward the Elder in England from their Kingdom of Wessex.[34]

Later Clann Cholmáin kings were descended from Flann, as was Congalach Cnogba, whose official pedigree pronounced him to be a member of the Síl nÁedo Sláine, the first of that branch of the Uí Néill to become King of Tara in two centuries, and whose last agnatic ancestor to have ruled from Tara was the eponymous Áed Sláine, ten generations before. Congalach was closely tied to Clann Cholmáin. His mother was Flann's daughter Lígach, and his paternal grandmother Eithne had been Flann's wife.[35]

Flann's son Donnchad Donn, his grandson Congalach Cnogba, and his great grandson Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, all held the kingship of Tara, Máel Sechnaill being the last of the traditional Uí Néill high kings.

Image

Flann was served by Máel Mura Othna (died 887), "chief poet of Ireland". In 885 Máel Mura composed the praise poem Flann for Érinn (Flann over Ireland). This linked Flann with the deeds of the legendary Uí Néill ancestor Túathal Techtmar. As Máire Herbert notes, Máel Mura depicts Tuathal as a 9th-century ruler, taking hostages from lesser kings, compelling their obedience and founding his kingship over Ireland on force. The high king in Flann for Érinn has authority over the fir Érenn (the men of Ireland) and leads them in war. This is very different from the way the kingship of Flann's 6th century ancestor Diarmait mac Cerbaill is portrayed in early sources.

A concrete testimony to Flann's claims survives in the high crosses erected at Clonmacnoise and Kinnitty on Flann's orders which name him and his father rí Érenn, "King of Ireland". At the same time, the oratory at Clonmacnoise was rebuilt in stone on Flann's orders.[36]

Flann is credited with commissioning the earliest known cumdach, an ornamented book case, for the Book of Durrow.[37]

See also

References

- ^ Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, pp. 233–238; Ó Corráin, "Ireland, Wales, Man, the Hebrides", pp. 83–88 & 93–94.

- ^ Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, p. 238.

- ^ Downham, Viking Kings, p. 13, table 4.

- ^ Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, pp. 238 & 244–247; Downham, Viking Kings, pp. 11–14, 274 & 276.; Ó Corráin, "Ireland, Wales, Man, the Hebrides", pp. 88–89.; Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, pp. 596–597; Byrne, Irish Kings, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, pp. 250–251; Downham, Viking Kings, pp. 12–16; Ó Corráin, "Ireland, Wales, Man, the Hebrides", p. 90; Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, pp. 596–597; Byrne, Irish Kings, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, pp. 251–255; Downham, Viking Kings, pp. 17–23, 137–145, 238–241, 246 & 258–259; Ó Corráin, "Ireland, Wales, Man, the Hebrides", p. 90; Woolf, "Pictland to Alba", pp. 106–116.

- ^ Byrne, Irish Kings, p. 91. Catherine Karkov also notes the possibility that it represents Abbot Colmán and Flann at the founding of the new church at Clonmacnoise; Karkov, Catherine E. (1997), "The Bewcastle Cross: Some iconographic problems", in Karkov, Catherine E.; Ryan, Michael; Farrell, Robert T. (eds.), The Insular Tradition, New York: SUNY Press, p. 24, ISBN 0-7914-3455-9

- ^ Herbert, p. 63; Charles-Edwards, pp. 596–598.

- ^ For Feidlimid's career, see Byrne, pp. 208–229; as noted by Ó Cróinín, pp.246–247, Giraldus Cambrensis apparently considered Feidlimid to have been king of Ireland. The previous non-Uí Néill King of Tara was Congal Cáech of the Dál nAraidi; see Charles-Edwards, pp. 494ff. The next would be Brian Bóruma.

- ^ Herbert, p.64; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 858.

- ^ Herbert, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Herbert, p.64; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 862; but see also Byrne, p. 266, who questions the meaning of the terminology used in later obits of kings of Tara.

- ^ For Áed Findliath's reign, see Byrne, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 877.

- ^ Woolf, "View", p. 92.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 882.

- ^ Ó Corráin, page number(s) wanting.

- ^ Quoted by Ó Cróinín, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 888; Woolf, "View", p. 93.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 889.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 893.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 898 & s.a. 902.

- ^ Hudson, Prophecy of Berchán, p. 77.

- ^ Duffy, Seán (15 January 2005). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-1-135-94824-5.

- ^ Bitel, Lisa M. (1 February 1994). Isle of the Saints: Monastic Settlement and Christian Community in Early Ireland. Cornell University Press. pp. 148–149. ISBN 0-8014-8157-0.

- ^ Hudson, Prophecy of Berchán, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Doherty, "Flann Sinna".

- ^ Byrne, pp. 163–164; Johnston.

- ^ Woolf. "View", p. 93.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 901.

- ^ Woolf, "View", p. 90.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 915.

- ^ Hudson, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Woolf, "View", p. 90, noting also that the Kings of Wessex faced comparable challenges from dispossessed branches of the Cerdicing dynasty.

- ^ Byrne, pp. 281–282; Woolf, "Pictish matriliny", p. 151.

- ^ Herbert, p. 64.

- ^ Ó Cróinín, pp. 83–84.

Bibliography

- Annals of Innisfallen, CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, 2000, retrieved 22 March 2008

- Annals of the Four Masters, CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, 2002, retrieved 22 March 2008

- Seán Mac Airt; Gearóid Mac Niocaill, eds. (1983). The Annals of Ulster (to AD 1131). Translated by Mac Airt; Mac Niocaill. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. retrieved 2008-03-22

- Chronicon Scotorum, CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, 2003, retrieved 22 March 2008

- Byrne, Francis John (1973), Irish Kings and High-Kings, London: Batsford, ISBN 0-7134-5882-8

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (30 November 2000), Early Christian Ireland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-36395-0

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2004). "Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid (d. 862)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17770. Retrieved 15 February 2007. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- De Paor, Liam (1997), Ireland and Early Europe: Essays and Occasional Writings on Art and Culture, Dublin: Four Courts Press, ISBN 1-85182-298-4

- Doherty, Charles (2004). "Donnchad Donn mac Flainn (d. 944)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50107. Retrieved 15 February 2007. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Doherty, Charles (2004). "Flann Sinna (847/8–916)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50117. Retrieved 15 February 2007. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Downham, Clare (2004), "The career of Cearbhall of Osraige", Ossory, Laois and Leinster, 1: 1–18, ISSN 1649-4938

- Downham, Clare (2007), Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014, Edinburgh: Dunedin, ISBN 978-1-903765-89-0

- Duffy, Seán, ed. (1997), Atlas of Irish History, Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, ISBN 0-7171-3093-2

- Herbert, Máire (2000), "Ri Éirenn, Ri Alban: kingship and identity in the ninth and tenth centuries", in Taylor, Simon (ed.), Kings, clerics and chronicles in Scotland 500–1297, Dublin: Four Courts, pp. 62–72, ISBN 1-85182-516-9

- Hudson, Benjamin (2004). "Áed mac Néill (d. 879)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50072. Retrieved 15 February 2007. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hudson, Benjamin (2004). "Cerball mac Dúngaile (d. 888)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4972. Retrieved 20 August 2007. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hudson, Benjamin; Harrison, B. (2004). "Niall mac Áeda (called Niall Glúndub) (c.869–919)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20077. Retrieved 25 October 2007. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hudson, Benjamin T. (1996), The Prophecy of Berchán: Irish and Scottish High-Kings of the Early Middle Ages, London: Greenwood, ISBN 0-313-29567-0

- Hughes, Kathleen (1972), Early Christian Ireland: Introduction to the Sources, The Sources of History, London: Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 0-340-16145-0

- Johnston, Elva (2004). "Gormlaith (d. 948)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50122. Retrieved 15 February 2007. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (1997), "Ireland, Wales, Man and the Hebrides", in Sawyer, Peter (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 83–109, ISBN 0-19-285434-8

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (1998), "The Vikings in Scotland and Ireland in the Ninth Century" (PDF), Peritia, 12, Belgium: Brepols: 296–339, doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.334, ISBN 2-503-50624-0, retrieved 1 December 2007

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (1998), "Viking Ireland – Afterthoughts", in Clarke; Ní Mhaonaigh; Ó Floinn (eds.), Ireland and Scandinavia in the early Viking age (PDF), Dublin: Four Courts, pp. 421–452, ISBN 1-85182-235-6, retrieved 20 August 2007

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí (1995), Early Medieval Ireland: 400–1200, The Longman History of Ireland, London: Longman, ISBN 0-582-01565-0

- Radner, Joan N., ed. (2004) [1975], Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, retrieved 10 February 2007

- Radner, Joan N. (1999), "Writing history: Early Irish historiography and the significance of form" (PDF), Celtica, 23, Dublin: School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Inst. for Advanced Studies: 312–325, ISBN 1-85500-190-X, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2009, retrieved 20 August 2007

- Woolf, Alex (2007), From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070, The New Edinburgh History of Scotland, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-1234-5

- Woolf, Alex (2001), "The View from the West: an Irish perspective on West Saxon dynastic practice", in Higham, N. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.), Edward the Elder 899–924, London: Routledge, pp. 89–101, ISBN 0-415-21496-3