A demigod is a half-god and half-human offspring of a god and a human,[1] or a human or non-human creature that is accorded divine status after death, or someone who has attained the "divine spark" (divine illumination). An immortal demigod often has tutelary status and a religious cult following, while a mortal demigod is one who has fallen or died, but is popular as a legendary hero in various polytheistic religions. Figuratively, it is used to describe a person whose talents or abilities are so superlative that they appear to approach being divine.

Etymology

The English term "demi-god" is a calque of the Latin word semideus, "half-god".[4] The Roman poet Ovid probably coined semideus to refer to less important gods, such as dryads.[5] Compare the Greek hemitheos. The term demigod first appeared in English in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, when it was used to render the Greek and Roman concepts of semideus and daemon.[4] Since then, it has frequently been applied figuratively to people of extraordinary ability.[6]

Classical

In the ancient Greek and Roman world, the concept of a demigod did not have a consistent definition and associated terminology rarely appeared.[7][need quotation to verify]

The earliest recorded use of the term occurs in texts attributed to the archaic Greek poets Homer and Hesiod. Both describe dead heroes as hemitheoi, or "half gods". In these cases, the word did not literally mean that these figures had one parent who was divine and one who was mortal.[8] Instead, those who demonstrated "strength, power, good family, and good behavior" were termed heroes, and after death they could be called hemitheoi,[9] a process that has been referred to as "heroization".[10] Pindar also used the term frequently as a synonym for "hero".[11]

According to the Roman author Cassius Dio, the Roman Senate declared Julius Caesar a demigod after his 46 BCE victory at Thapsus.[12] However, Dio was writing in the third century CE — centuries after the death of Caesar — and modern critics have cast doubt on whether the Senate really did this.[13]

The first Roman to employ the term "demigod" may have been the poet Ovid (17 or 18 CE), who used the Latin semideus several times in reference to minor deities.[14] The poet Lucan (39-65) also uses the term to speak of Pompey attaining divinity upon his death in 48 BCE.[15] In later antiquity, the Roman writer Martianus Capella (fl. 410-420) proposed a hierarchy of gods as follows:[16]

- the gods proper, or major gods

- the genii or daemones

- the demigods or semones (who dwell in the upper atmosphere)

- the manes and ghosts of heroes (who dwell in the lower atmosphere)

- the earth-dwelling gods like fauns and satyrs

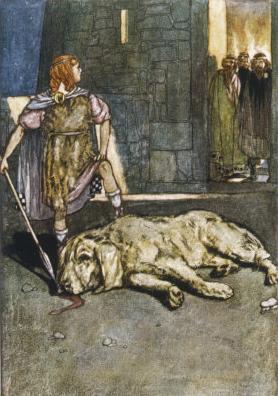

Celtic

The Celtic warrior Cú Chulainn, a major protagonist in the Irish national epic the Táin Bo Cuailnge, ranks as a hero or as a demigod.[17] He is the son of the Irish god Lugh and the mortal princess Deichtine.[18]

In the immediate pre-Roman period, the Celtic Gallaceian tribe in Portugal made powerful, large stone statues of deified local heroes, which stood on hill forts in the mountainous regions of - what is today - Northern Portugal and Spanish Galicia.

Hinduism

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

In Hinduism, the term demigod is used to refer to deities who were once human and later became devas (gods). There are two notable demigods in Vedic Scriptures:

Nandi (the divine vehicle of Shiva), and Garuda (the divine vehicle of Vishnu).[19] Examples of demigods worshiped in South India are Madurai Veeran and Karuppu Sami.

The heroes of the Hindu epic Mahabharata, the five Pandava brothers and their half brother Karna, fit the Western definition of demigods though they are generally not referred to as such. Queen Kunti, the wife of King Pandu, was given a mantra that, when recited, meant that one of the gods would give her his child. When her husband was cursed to die if he ever engaged in sexual relations, Kunti used this mantra to provide her husband with children fathered by various deities. These children were Yudhishthira (child of Dharmaraj), Bhima (child of Vayu) and Arjuna (child of Indra). She taught this mantra to Madri, King Pandu's other wife, and she immaculately conceived twin boys named Nakula and Sahadeva (children of the Ashvins). Queen Kunti had previously conceived another son, Karna, when she had tested the mantra out. Despite her protests, Surya the sun god was compelled by the mantra to impregnate her. Bhishma is another figures who fits the western definition of demigod, as he was the son of King Shantanu and Goddess Ganga.

The Vaishnavites (who often translate deva as "demigod") cite various verses that speak of the devas' subordinate status. For example, the Rig Veda (1.22.20) reads, "oṃ tad viṣṇoḥ paramam padam sadā paśyanti sūrayaḥ", which translates to, "All the suras [i.e., the devas] look always toward the feet of Lord Vishnu". Similarly, in the Vishnu Sahasranama, the concluding verses, read, "The Rishis [great sages], the ancestors, the devas, the great elements, in fact, all things moving and unmoving constituting this universe, have originated from Narayana," (i.e., Vishnu). Thus the Devas are stated to be subordinate to Vishnu, or God.

A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) translates the Sanskrit word "deva" as "demigod" in his literature when the term referred to a God other than the Supreme Lord. This is because the Vaishnava tradition teaches that there is only one Supreme Lord and that all others are but His servants. In an effort to emphasize their subservience, Prabhupada uses the word "demigod" as a translation of deva. However, there are at least three occurrences in the eleventh chapter of Bhagavad-Gita where the word deva, used in reference to Lord Krishna, is translated as "Lord". The word deva can be used to refer to the Supreme Lord, celestial beings, and saintly souls depending on the context. This is similar to the word Bhagavan, which is translated according to different contexts.

China

Among the demigods in Chinese mythology, Erlang Shen and Chen Xiang are most prominent. In the Journey to the West, the Jade Emperor's younger sister Yaoji is mentioned to have descended to the mortal realm and given birth to a child named Yang Jian. He would eventually grow up to become a deity himself known as Erlang Shen.[20]

Chen Xiang is nephew of Erlang Shen, birth by his younger sister Huayue Sanniang who married with a mortal scholar.[20]

Japan

Abe no Seimei, a famous onmyōji from the Heian period was supposed to be one. His father, Abe no Yasuna (安倍 保名), was human. Still, his mother Kuzunoha, was a Kitsune, a divine fox, being this the origin of Abe no Seimei's magical prowess.

Anitism

In the indigenous religions originating from the Philippines, collectively called Anitism, demigods abound in various ethnic stories. Many of these demigods equal major gods and goddesses in power and influence. Notable examples include Mayari, the Tagalog moon goddess who governs the world every night,[21][22] Tala, the Tagalog star goddess,[21] Hanan, the Tagalog morning goddess,[21] Apo Anno, a Kankanaey demigod hero,[23] Oryol, a Bicolano half-snake demi-goddess who brought peace to the land after defeating all beasts in Ibalon,[24] Laon, a Hiligaynon demigod who can talk to animals and defeated the mad dragon at Mount Kanlaon,[25] Ovug, an Ifugao thunder and lightning demigod who has separate animations in both the upper and earth worlds,[26] Takyayen, a Tinguian demigod and son of the star goddess Gagayoma,[27] and the three Suludnon demigod sons of Alunsina, namely Labaw Dongon, Humadapnon, and Dumalapdap.[28]

Polynesian

Samoan

Tongan

Māori

Hawaii

See also

References

- ^ Woody Lamonte, G. (2002). Black Thoughts for White America. ISBN 9780595261659.

- ^ Siikala, Anna-Leena (2013). Itämerensuomalaisten mytologia. Finnish Literature Society. ISBN 978-952-222-393-7.

- ^ Siikala, Anna-Leena (30 July 2007). "Väinämöinen". Kansallisbiografia. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ a b Oxford English Dictionary. Vol. 3. UK: Oxford University Press. 1961. p. 180.

- ^

Weinstock, Stefan (1971). Divus Julius (Reprinted ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 53. ISBN 0198142870.

[...] 'semideus' [...] seems to have been coined by Ovid.

- ^ "demigod". Collins English Dictionary. Collins. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ Talbert, Charles H. (January 1, 1975). "The Concept of Immortals in Mediterranean Antiquity". Journal of Biblical Literature. 94 (3): 419–436. doi:10.2307/3265162. ISSN 0021-9231. JSTOR 3265162.

- ^ William, Hansen (2005). Classical Mythology: A Guide to the Mythical World of the Greeks and Romans. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 199. ISBN 0195300351.

- ^ Nagy, Gregory (2018). Greek Mythology and Poetics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-150-173-202-7.

- ^ Price, Theodora Hadzisteliou (1 January 1973). "Hero-Cult and Homer". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 22 (2): 129–144. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4435325.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1894). A Greek–English Lexicon (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 596.

- ^ Dio, Cassius. Roman History. 43.21.2.

- ^ Fishwick, Duncan (January 1, 1975). "The Name of the Demigod". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 24 (4): 624–628. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4435475.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1980). An Elementary Latin Dictionary (Revised ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 767. ISBN 9780198642015.

- ^ Lucan. The Civil War. Vol. Book 9.

- ^ Capella, Martianus. De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii. 2.156.

- ^

Macbain, Alexander, ed. (1888). "The Celtic Magazin". 13. Inverness: A. and W. Mackenzie: 282.

The Irish Fraoch is a demigod, and his story presents that curious blending of the rationalised supernatural - that is , the euhemerised or minimised supernatural - with the usual incidents of a hero's life, a blending which is characteristic of Irish tales about Cuchulain and the early heroes, who, in reality, are only demigods, but who have been fondly deemed by ancient tale-tellers and modern students to have been real historical characters exaggerated into mythic proportions.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ward, Alan (2011). The Myths of the Gods: Structures in Irish Mythology. p.13

- ^ George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 21, 24, 63, 138. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2., Quote: "His vehicle was Garuda, the sun bird" (p. 21); "(...) Garuda, the great sun eagle, (...)" (p. 74)

- ^ a b Yuan, Haiwang (2006). The Magic Lotus Lantern and Other Tales From the Han Chinese. Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 1-59158-294-6.

- ^ a b c Notes on Philippine Divinities, F. Landa Jocano

- ^ Philippine Myths, Legends, and Folktales | Maximo Ramos | 1990

- ^ "Benguet community races against time to save Apo Anno". 5 February 2019. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Three Tales From Bicol, Perla S. Intia, New Day Publishers, 1982

- ^ Philippine Folk Literature: The Myths, Damiana L. Eugenio, UP Press 1993

- ^ Beyer, 1913

- ^ Cole M. C., 1916

- ^ Hinilawod: Adventures of Humadapnon, chanted by Hugan-an and recorded by Dr. F. Landa Jocano, Metro Manila: 2000, Punlad Research House, ISBN 9716220103

External links

Media related to Demigods at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Demigods at Wikimedia Commons