| Philip the Arab | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

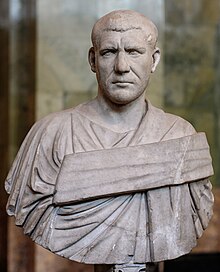

Bust of Philip I at The State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, 2010 | |||||||||

| Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||||||

| Reign | February 244 – September 249 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Gordian III | ||||||||

| Successor | Decius | ||||||||

| Co-emperor | Philip II (248–249) | ||||||||

| Born | c. 204 Philippopolis, Arabia Petraea, Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Died | September 249 (aged 45) Verona, Italia, Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||

| Issue | Philip II | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Father | Julius Marinus | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman paganism (publicly) Christianity (speculated)[2] | ||||||||

Philip I (Latin: Marcus Julius Philippus; c. 204 – September 249), commonly known as Philip the Arab, was the Emperor of the Roman Empire from 244 to 249. After the death of Gordian III in February 244, Philip, who had been Praetorian prefect, rose to power. He quickly negotiated peace with the Sasanian Empire and returned to Rome to be confirmed by the Senate.

Although his reign lasted only five years, it marks an unusually stable period in a century that is otherwise known for having been turbulent.[a][b] Near the end of his rule, Philip commemorated Rome's first millennium. In September 249, during the Battle of Verona, he was betrayed and killed by Decius, who promptly usurped the throne before being recognized by the Senate as his successor.

Born in modern-day Shahba, Syria, in what was then Arabia Petraea, Philip's ethnicity was not attested with certainty, but he was most likely an Arab. While he publicly adhered to the Roman religion, he was later asserted to have been a Christian, and in the later half of the 3rd century and into the beginning of the 4th century, some Christian clergymen held that Philip had been the first Christian ruler of Rome. He was described as such in many published works that became widely known during the Middle Ages, including: Chronicon (lit. 'Chronicle'); Historiae Adversus Paganos (lit. 'History Against the Pagans'); and Historia Ecclesiastica (lit. 'Ecclesiastical History').[5] Consequently, Philip's religious affiliation remains a divisive topic in modern scholarly debate about his life.

Early life

Little is known about Philip's early life and political career. He was born in what is today Shahba, Syria, about 90 kilometres (56 mi) southeast of Damascus, in Trachonitis.[6] His birth city, later renamed Philippopolis, lay within Aurantis, an Arab district which at the time was part of the Roman province of Arabia Petraea.[7] Most historians accept that Philip was, indeed, an Arab,[7][8][9][10][11] but this ethnic identification remains uncertain.[12] He was the son of a local citizen, Julius Marinus, possibly of some importance.[13] Allegations from later Roman sources (Historia Augusta and Epitome de Caesaribus) that Philip had a very humble origin or even that his father was a leader of brigands are not accepted by modern historians.[14] His birth date is not recorded by contemporary sources, but the 7th-century Chronicon Paschale records that he died at the age of 45.[15]

While the name of Philip's mother is unknown, he did have a brother, Gaius Julius Priscus, an equestrian and a member of the Praetorian Guard under Gordian III (238–244).[16] Philip was married to Marcia Otacilia Severa, daughter of a Roman governor. They had a son, Philip II, born in 237 or 238.[13]

The rise to the purple of the Severans from nearby Emesa is noted as a motivational factor in Philip's own ascent, due to geographic and ethnic similarity between himself and the Emesan emperors.[c][d]

Accession to the throne

Philip's rise to prominence began through the intervention of his brother Priscus, who was an important official under the emperor Gordian III.[13] His big break came in 243, during Gordian III's campaign against Shapur I of Persia, when the Praetorian prefect Timesitheus died under unclear circumstances.[21] At the suggestion of his brother Priscus, Philip became the new Praetorian prefect, with the intention that the two brothers would control the young Emperor and rule the Roman world as unofficial regents.[13] Following a military defeat, Gordian III died in February 244 under circumstances that are still debated. While some claim that Philip conspired in his murder, other accounts (including one coming from the Persian point of view) state that Gordian died in battle.[21][6][22] Whatever the case, Philip assumed the purple robe following Gordian's death.

Philip was not willing to repeat the mistakes of previous claimants, and was aware that he had to return to Rome in order to secure his position with the Senate.[6] However, his first priority was to conclude a peace treaty with Shapur, and withdraw the army from a potentially disastrous situation.[6][23] Although Philip was accused of abandoning territory, the actual terms of the peace were not as humiliating as they could have been.[23] Philip apparently retained Timesitheus’ reconquest of Osroene and Mesopotamia, but he had to agree that Armenia lay within Persia's sphere of influence.[24] He also had to pay an enormous indemnity to the Persians of 500,000 denarii.[24][23] Philip immediately issued coins proclaiming that he had made peace with the Persians (pax fundata cum Persis).[23]

Leading his army back up the Euphrates, south of Circesium Philip erected a cenotaph in honor of Gordian III, but his ashes were sent ahead to Rome, where he arranged for Gordian III's deification.[6][25] Whilst in Antioch, he left his brother Priscus as extraordinary ruler of the Eastern provinces, with the title of rector Orientis.[6][23][13] Moving westward, he gave his brother-in-law Severianus control of the provinces of Moesia and Macedonia.[26] He arrived in Rome in the late summer of 244, where he was confirmed augustus.[6] Before the end of the year, he nominated his young son caesar (heir), his wife, Marcia Otacilia Severa, was named augusta, and he also deified his father Marinus, even though the latter had never been emperor.[23] While in Rome, Philip also claimed a victory over the Persians with the titles of Persicus Maximus, Parthicus Maximus and Parthicus Adiabenicus (the latter probably unofficially).[27]

Reign

In an attempt to shore up his regime, Philip put a great deal of effort in maintaining good relations with the Senate, and from the beginning of his reign, he reaffirmed the old Roman virtues and traditions.[23] He quickly ordered an enormous building program in his home town, renaming it Philippopolis, and raising it to civic status, while he populated it with statues of himself and his family.[25] He also introduced the Actia-Dusaria Games in Bostra, capital of Arabia. This festival combined the worship of Dushara, the main Nabataean deity, with commemoration of the Battle of Actium, as part of the Roman Imperial cult.[28]

The creation of the new city of Philippopolis, piled on top of the massive tribute owed to the Persians, as well as the necessary donativum to the army to secure its acceptance of his accession, made Philip desperately short of money.[25] To pay for it, he ruthlessly increased levels of taxation, while at the same time he ceased paying subsidies to the tribes north of the Danube that were vital for keeping the peace on the frontiers.[29] Both decisions would have significant impacts upon the empire and his reign.[30]

At the frontiers of the Roman Empire

In 245, Philip was forced to leave Rome as the stability established by Timesitheus was undone by a combination of his death, Gordian's defeat in the east and Philip's decision to cease paying the subsidies.[6][30] The Carpi moved through Dacia, crossed the Danube and emerged in Moesia where they threatened the Balkans.[31] Establishing his headquarters in Philippopolis in Thrace, he pushed the Carpi across the Danube and chased them back into Dacia, so that by the summer of 246, he claimed victory against them, along with the title "Carpicus Maximus".[32][33] In the meantime, the Arsacids of Armenia refused to acknowledge the authority of the Persian king Shapur I, and war with Persia flared up again by 245.[30]

Ludi Saeculares

Nevertheless, Philip was back in Rome by August 247, where he poured more money into the most momentous event of his reign – the Ludi Saeculares, which coincided with the one thousandth anniversary of the foundation of Rome.[32] So in April 248 AD (April 1001 A.U.C.), Philip had the honor of leading the celebrations of the one thousandth birthday of Rome, which according to the empire's official Varronian chronology was founded on 21 April 753 BC by Romulus.

Commemorative coins, such as the one illustrated at left, were issued in large numbers and, according to contemporary accounts, the festivities were magnificent and included spectacular games, ludi saeculares, and theatrical presentations throughout the city.[34] In the Colosseum, in what had been originally prepared for Gordian III's planned Roman triumph over the Persians,[35] more than 1,000 gladiators were killed along with hundreds of exotic animals including hippos, leopards, lions, giraffes, and one rhinoceros.[36] The events were also celebrated in literature, with several publications, including Asinius Quadratus' History of a Thousand Years, specially prepared for the anniversary.[13] At the same time, Philip elevated his son to the rank of co-augustus.[13]

Downfall

Despite the festive atmosphere, there were continued problems in the provinces. In late 248, the legions of Pannonia and Moesia, dissatisfied with the result of the war against the Carpi, rebelled and proclaimed Tiberius Claudius Pacatianus emperor.[13] The resulting confusion tempted the Quadi and other Germanic tribes to cross the frontier and raid Pannonia.[32] At the same time, the Goths invaded Moesia and Thrace across the Danube frontier, and laid siege to Marcianopolis,[37] as the Carpi, encouraged by the Gothic incursions, renewed their assaults in Dacia and Moesia.[32] Meanwhile, in the East, Marcus Jotapianus led another uprising in response to the oppressive rule of Priscus and the excessive taxation of the Eastern provinces.[13][26] Other usurpers, like Marcus Silbannacus are reported to have started rebellions without much success.[13]

Overwhelmed by the number of invasions and usurpers, Philip offered to resign, but the Senate decided to throw its support behind the emperor, with a certain Gaius Messius Quintus Decius most vocal of all the senators.[38] Philip was so impressed by his support that he dispatched Decius to the region with a special command encompassing all of the Pannonian and Moesian provinces. This had a dual purpose of both quelling the rebellion of Pacatianus as well as dealing with the barbarian incursions.[38][32]

Although Decius managed to quell the revolt, discontent in the legions was growing.[30] Decius was proclaimed emperor by the Danubian armies in the spring of 249 and immediately marched on Rome.[38][13] Yet even before he had left the region, the situation for Philip had turned even more sour. Financial difficulties had forced him to debase the antoninianus, as rioting began to occur in Egypt, causing disruptions to Rome's wheat supply and further eroding Philip's support in the capital.[39]

Although Decius tried to come to terms with Philip,[38] Philip's army met the usurper near modern Verona that summer. Decius easily won the battle and Philip was killed sometime in September 249,[40][39] either in the fighting or assassinated by his own soldiers who were eager to please the new ruler.[13] Philip's eleven-year-old son and heir may have been killed with his father and Priscus disappeared without a trace.[40]

Attitude towards Christianity

Some later traditions, first mentioned by the historian Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History, held that Philip was the first Christian Roman Emperor. According to Eusebius (Ecc. Hist. VI.34), Philip was a Christian, but was not allowed to enter Easter vigil services until he confessed his sins and was ordered to sit among the penitents, which he did willingly. Later versions located this event in Antioch.[13]

However, historians generally identify the later Emperor Constantine, baptized on his deathbed, as the first Christian emperor, and generally describe Philip's adherence to Christianity as dubious, because non-Christian writers do not mention the fact, and because throughout his reign, Philip to all appearances (coinage, etc.) continued to follow the state religion.[41] Critics ascribe Eusebius' claim as probably due to the tolerance Philip showed towards Christians.

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ "The five years of Philip's reign were a time of uncommon stability and repose in a century notorious for turbulence".[3]

- ^ "Philip's reign was brief – just five years – but it was a stable one in the unstable third century."[4]

- ^ "Severus deserves the ultimate credit for making possible the emergence of a figure such as Philip".[7]

- ^ "The spectacle of Arab and half-Arab emperors from neighboring Emesa must have left a deep impression on Marcus Julius Philippus."[17]

- ^ The two emperors who are named are shown in the way they are described: Philip the Arab is kneeling, asking for peace, and Valerian is physically taken prisoner by Šāpur. Consequently, the relief must be made after 260 AD. "[18]

- ^ "(...) while another figure, probably Philip the Arab, kneels, and the Sasanian king holds the ill-fated Emperor Valerian by his wrist."[19]

- ^ "He recorded these deeds for posterity in both words and images at Naqsh-i Rustam and on the Ka'aba-i Zardušt near the ancient Achaemenid capital of Persepolis, preserving for us a vivid image of two Roman emperors, one kneeling (probably Philip the Arab, also defeated by Shapur) and the second (Valerian), uncrowned and held captive at the wrist by a gloriously mounted Persian king."[20]

Citations

- ^ Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 498. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- ^ McGuckin, John Anthony (15 December 2010). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-9254-8.

- ^ Bowersock 1983, p. 124.

- ^ Ball 2000, p. 468.

- ^ Shahîd 1984, pp. 65–93.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bowman, Cameron & Garnsey 2005, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Bowersock 1983, p. 122.

- ^ Ball 2000, p. 418.

- ^ Shahîd 1984, p. 36.

- ^ "Philip | Roman emperor". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Perry Anderson, Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism (London: NLB, 1974), 87–88.

- ^ Fratantuono, Lee (2020). Roman Conquests: Mesopotamia and Arabia. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-4738-8326-0.

We cannot be certain that Philip was of Arab origin...

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Meckler 1999.

- ^ Bowersock 1983, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Chronicon Paschale, Olympiad 257.

- ^ Potter 2004, p. 232.

- ^ Shahîd 1984, p. 37.

- ^ Overlaet, Bruno (2017). "Šāpur I: Rovk Reliefs". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 274. ISBN 978-1610693912.

- ^ Corcoran, Simon (2006). "Before Constantine". In Lenski, Noel (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0521521574.

- ^ a b Southern 2001, p. 70.

- ^ Potter 2004, p. 234.

- ^ a b c d e f g Southern 2001, p. 71.

- ^ a b Potter 2004, p. 237.

- ^ a b c Potter 2004, p. 238.

- ^ a b Potter 2004, p. 239.

- ^ Kienast, Dietmar; Werner Eck & Matthäus Heil (2017) [1990]. Römische Kaisertabelle. WBG. pp. 190–194. ISBN 978-3-534-26724-8.

- ^ Bowersock 1983, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Potter 2004, pp. 238–239.

- ^ a b c d Potter 2004, p. 240.

- ^ Bowman, Cameron & Garnsey 2005, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b c d e Bowman, Cameron & Garnsey 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Southern 2001, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Southern 2001, p. 72.

- ^ Martial; Coleman, Kathleen M., M. Valerii Martialis Liber Spectaculorum (2006), pg. lvi

- ^ Graham, T. (Writer and Director). (2000). The Fall [Television series episode]. In T. Graham (Producer), Rome: Power and Glory. Military Channel.

- ^ Southern 2001, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d Southern 2001, p. 74.

- ^ a b Bowman, Cameron & Garnsey 2005, p. 38.

- ^ a b Potter 2004, p. 241.

- ^ Cruse, C.F., translator. Eusebius' Ecclesiastical History, Hendrickson Publishers, 1998 (fourth printing, 2004), pp. 220–221.

General and cited sources

Primary sources

- Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribus

- Orosius, Histories against the Pagans, vii.20

- Joannes Zonaras, Compendium of History extract: Zonaras: Alexander Severus to Diocletian: 222–284

- Zosimus, Historia Nova

Secondary sources

- Ball, Warwick (2000). Rome in the East : the Transformation of an Empire. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0203023228. OCLC 49414893.

- Bowman, Alan; Cameron, Averil; Garnsey, Peter, eds. (8 September 2005). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 12, The crisis of Empire, AD 193–337. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/chol9780521301992. ISBN 978-1139053921. OCLC 828737952.

- Bowersock, Glenn Warren (1983). Roman Arabia. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674777552. OCLC 1245763862 – via Internet Archive.

- Meckler, Michael L. (7 June 1999). "Philip the Arab (244–249 A.D.)". De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors.

- Potter, David Stone (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay : AD 180–395. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0203401170. OCLC 52430927.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1984). Rome and the Arabs : a prolegomenon to the study of Byzantium and the Arabs. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0884021155. OCLC 1245769052 – via Internet Archive.

- Southern, Pat (2001). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415239431. OCLC 46421874.

External links

- A brief bio from an educational Site on Roman Coins

- . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Philip the Arab

- 200s births

- 249 deaths

- People from Roman Arabia

- Arabs in the Roman Empire

- 3rd-century Arab people

- 3rd-century Roman emperors

- 3rd-century praetorian prefects

- Crisis of the Third Century

- Deified Roman emperors

- 3rd-century Roman consuls

- Julii

- People from as-Suwayda Governorate

- Roman emperors killed in battle

- Roman pharaohs

- Damnatio memoriae