Ernest J. King | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1945 | |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Born | 23 November 1878 Lorain, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | 25 June 1956 (aged 77) Kittery, Maine, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1901–1956 |

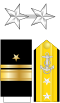

| Rank | Fleet admiral |

| Commands | |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | |

| Other work | President, Naval Historical Foundation |

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was a fleet admiral in the United States Navy who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. He was the U.S. Navy's second-most senior officer in World War II after Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, who served as Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief. He directed the United States Navy's operations, planning, and administration and was a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Combined Chiefs of Staff.

King graduated fourth in the United States Naval Academy class of 1901. He received his first command in 1914, of the destroyer USS Terry in the occupation of Veracruz. During World War I, he served on the staff of Vice Admiral Henry T. Mayo, the commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet. After the war, King was the head of the Naval Postgraduate School and commanded submarine divisions. He directed the salvage of the submarine USS S-51, earning the first of his three Navy Distinguished Service Medals, and later that of the USS S-4. He qualified as a naval aviator in 1927, and was captain of the aircraft carrier USS Lexington. He then served as Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics. Following a period on the Navy's General Board, he became commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet in February 1941. Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, King was appointed as COMINCH, and in March 1942, he succeeded Admiral Harold R. Stark as CNO, holding these two positions for the duration of the war. He also commanded the Tenth Fleet, which played an important role in the fight against the German U-boats in the Second Battle of the Atlantic. He participated in the top-level Allied World War II conferences, and took the lead in formulating the strategy of the Pacific War. In December 1944, he became the second admiral to be promoted to the new rank of fleet admiral. He left active duty in December 1945 and died in Kittery, Maine, in 1956.

Early life and education

Ernest Joseph King was born in Lorain, Ohio, on 23 November 1878, the second child of James Clydesdale King, a Scottish immigrant from Bridge of Weir, Renfrewshire, and his wife Elizabeth (Bessie) née Keam, an immigrant from Plymouth, England. His father initially worked as a bridge builder, but moved to Lorain, where he worked in a railway repair shop. He had an older brother who died in infancy, two younger brothers and two younger sisters:[1] Maude (who died aged seven), Mildred, Norman and Percy.[2]

The family moved to Uhrichsville, Ohio, when his father took a position with the Pennsylvania Railroad workshops, but returned to Lorain a year later. When King was eleven years old, the family moved to Cleveland, where his father was a foreman at the Valley Railway workshops, and King was educated at the Fowler School. He decided to go to work rather than high school, and took a position with a company that made typesetting machines. When it closed he went to work for his father. After a year, the family returned to Lorain, and King entered Lorain High School.[2] He graduated as valedictorian in the Class of 1897; his commencement speech was titled "Uses of Adversity".[3][4] The school was a small one; there were only thirteen classmates in his year.[5]

King secured an appointment to the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, from his local Congressman, Winfield Scott Kerr, after passing physical and written examinations in Mansfield, Ohio, ahead of thirty other applicants.[6] He entered Annapolis as a naval cadet on 18 August 1897. He acquired the nickname "Rey", the Spanish word for "king".[7]

During the summer breaks, naval cadets served on ships to accustom them to life at sea. While still at the Naval Academy, King served on the cruiser USS San Francisco during the Spanish–American War.[8] During his senior year at the academy, he attained the rank of cadet lieutenant commander, the highest naval cadet ranking at that time. He graduated in June 1901, ranked fourth in his class of sixty-seven. The graduation address was given by the Vice President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, who handed out the diplomas.[9]

Surface ships

Far East cruise

Graduates like King who went into the Navy had to serve for two years at sea before being commissioned as ensigns.[9] King took a short course in torpedo design and operation at the Naval Torpedo Station at Newport, Rhode Island. He then became the navigator of the survey ship USS Eagle, which conducted surveys of Cienfuegos Bay in Cuba. An eye injury resulted in his being sent to the Brooklyn Naval Hospital.[10] When he recovered, he was ordered to report to the battleship USS Illinois, which was berthed in Brooklyn.[10] The Illinois was the flagship of Rear Admiral Arent S. Crowninshield, and King got to know Crowninshield's staff well. The staff offered him an assignment on the cruiser USS Cincinnati, which was headed overseas, bound for the Far East via the Suez Canal.[10]

King was promoted to ensign on 7 June 1903,[11] having taken his examination while the Cincinnati was in Europe.[12] The Cincinnati spent several weeks at anchor in Manila Bay, where it conducted target practice. In February 1904 it sailed to Korea, where the Russo-Japanese War had broken out. It remained in Korean waters until October, when it went to China. It was back in Manila for more target practice in February and March 1905 before returning to China. In June 1906, it escorted the Russian cruisers Oleg, Aurora and Zhemchug, survivors of the Battle of Tsushima, into Manila Bay, where they were interned.[13]

Bouts of heavy drinking led to King being put under hatches, and a forthright and arrogant attitude bordering on insubordination led to adverse comments in his fitness reports.[14] When he heard heard that members of the Annapolis class of 1902 were being sent home from the Asiatic Fleet, he sought and obtained an audience with Rear Admiral Charles J. Train. Train agreed that King was entitled to go home and arranged for him to travel on the former hospital ship USS Solace, which departed on 27 June.[15]

Marriage and Annapolis

On returning to the United States, King rejoined his fiancée, Martha Rankin ("Mattie") Egerton, a Baltimore socialite he had met while at the Naval Academy.[16] They had become engaged in January 1903.[17] She was living at West Point, New York, with her sister Florence,[18] who had married an Army officer, Walter D. Smith.[19] King and Egerton were married in a ceremony in the West Point Cadet Chapel on 10 October 1905.[20][21] They had six daughters, Claire, Elizabeth, Florence, Martha, Eleanor and Mildred; and a son, Ernest Joseph King Jr.[22] Mattie considered educated women to be vulgar. She took little interest in King's naval career, and confined her activities to her children and domestic affairs.[23]

King's next assignment was as a gunnery officer on the battleship USS Alabama. King became a critic of shipboard organization, which was largely unchanged since the days of sail. He published his thoughts in Some Ideas About Organization on Board Ship in the United States Naval Institute Proceedings, which won a prize for best essay in 1909. "The writer fully realizes the possible opposition," he wrote, "for if there is anything more characteristic of the navy than its fighting ability, it is its inertia to change, or conservatism, or the clinging to things that are old because they are old."[24][25] In addition to a gold medal, the prize came with $500 (equivalent to $17,000 in 2023) and a lifetime membership of the United States Naval Institute.[26]

Due to the expansion of the navy, officers like King who had served three years at sea as an ensign became eligible for promotion to lieutenant; only the few who failed to pass the examinations were promoted to lieutenant (junior grade). This involved traveling to Washington, D.C., for ten days of physical examinations and tests of his professional knowledge in May 1906.[27] The final hurdle was an appearance before the selection board, which drew attention to his record of punishments for drinking and insubordination, before congratulating King on his promotion, which became effective on 7 June 1906.[24]

Duty afloat alternated with duty ashore, so King's next assignment was at Annapolis, where he taught ordnance, gunnery and seamanship. This posting reunited him with Mattie, who had been living with her family in Baltimore. After two years he became the officer in charge of discipline at Bancroft Hall.[28] King returned to sea duty in 1909, as flag secretary to Rear Admiral Hugo Osterhaus. After a year, Osterhaus was transferred to shore duty, and King joined the engineering department of the battleship USS New Hampshire. He soon became the engineering officer. After a year on New Hampshire, Osterhaus returned to sea duty and King became his flag secretary once more. Fellow officers on the staff included Dudley Knox as fleet gunnery officer and Harry E. Yarnell as fleet engineering officer. King returned to shore duty at Annapolis in May 1912 as executive officer of the Naval Engineering Experiment Station. While there, he served as the secretary-treasurer of the Naval Institute, editing and publishing papers in the Proceedings.[29] He was promoted to lieutenant commander on 1 July 1913.[11]

World War I

When war with Mexico threatened in 1913, King went to Washington, D.C., to lobby for command of a destroyer. He received his first command, the destroyer USS Terry on 30 April 1914, participating in the United States occupation of Veracruz, escorting a mule transport from Galveston, Texas. He then moved on to his second command, a more modern destroyer, the USS Cassin on 18 July 1914. He also served as an aide-de-camp to the commander of the Atlantic Fleet destroyer flotilla, Captain William S. Sims.[11][30]

In December 1915, King joined the staff of Vice Admiral Henry T. Mayo, the Commander in Chief, of the Atlantic Fleet. After the United States entered World War I, King went to the UK as part of Mayo's staff. He was a frequent visitor to the Royal Navy and occasionally saw action as an observer on board British ships.[31] He was awarded the Navy Cross "for distinguished service in the line of his profession as assistant chief of staff of the Atlantic Fleet."[32] He was promoted to commander on 1 July 1917 and captain on 21 September 1918.[11] After the war King adopted his signature manner of wearing his uniform with a breast-pocket handkerchief below his ribbons. Officers serving alongside the Royal Navy did this in emulation of the British Admiral David Beatty, the commander of the British Grand Fleet. King was the last to continue this tradition.[33][34]

After the war ended in November 1918, King became head of the Naval Postgraduate School in Annapolis. He bought a house there, where his family lived from then on. With Captains Dudley Knox and William S. Pye, King prepared a report on naval training that recommended changes to naval training and career paths, which gained wide circulation when he published it in the Proceedings. Most of the report's recommendations were accepted and eventually became policy.[35][36] In 1921, King heard that Rear Admiral Henry B. Wilson, an officer whose stance on naval education he disliked, was to become the Superintendent of the Naval Academy. King approached Captain William D. Leahy about an early return to sea duty. Leahy told him he was too junior for a seagoing captain's command, and that nothing was available. After some discussion, King eventually accepted command of USS Bridge, a stores ship. Although auxiliaries like Bridge served a vital role, such a command was regarded as boring and was avoided by ambitious officers.[37]

Submarines

After a year, King again approached Leahy about securing command of a destroyer division or flotilla and again was told that nothing was available. Leahy then suggested that if King was interested in submarines, he could offer him command of a submarine division. King accepted.[37] King attended a short training course at the Submarine School in New London, Connecticut, before taking command of a submarine division, flying his commodore's pennant from USS S-20. He never earned his Submarine Warfare insignia (dolphins), although he proposed and designed the now-familiar dolphin insignia.[38] On 4 September 1923, he took over command of the Naval Submarine Base at New London.[39]

From September 1925 to July 1926, King directed the salvage of USS S-51, earning the first of his three Navy Distinguished Service Medals. The task was a demanding one: S-51 lay on the bottom with a large gash on the side in 130 feet (40 m) of water near Block Island, and navy salvage divers were not accustomed to working below 90 feet (27 m). The submarine was raised by sealing compartments and forcing the water out of them with compressed air. Eight pontoon floats were added to make it buoyant again. Just as they were ready to raise it, a storm hit and the submarine suddenly rose to the surface. After an attempt to tow it failed, King made the difficult decision to sink it again. Eventually the divers succeeded in raising it and getting it to the New York Navy Yard.[40]

Aviation

Aviator training

In 1925, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, asked King if he would consider a transfer to naval aviation. King was unable to accept the offer at that time due to the salvage of S-51, and he wanted command of a cruiser, which Leahy was unable to offer. King then accepted Moffett's offer, although he still hoped for a cruiser.[41] He assumed command of the aircraft tender USS Wright, with additional duties as senior aide on the staff of Commander, Air Squadrons, Atlantic Fleet.[42]

That year, the United States Congress passed a law (10 USC Sec. 5942) requiring commanders of all aircraft carriers, seaplane tenders, and aviation shore establishments be qualified naval aviators or naval aviation observers. King therefore reported to Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida, for aviator training in January 1927. He was the only captain in his class of twenty; although it also included Commander Richmond K. Turner, most of the class were ensigns or lieutenants. King received his wings as Naval Aviator No. 3368 on 26 May 1927 and resumed command of Wright.[43][44]

Between 1926 and 1936 King flew an average of 150 hours annually.[45] For a time, he frequently flew solo, flying to Annapolis for weekend visits with his family, but his solo flying was eliminated by a naval regulation prohibiting them for aviators aged 50 or over.[43] King commanded Wright until 1929, except for a brief interlude overseeing the salvage of USS S-4,[46] for which he was awarded a gold star to his Distinguished Service Medal.[47] He then became Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics under Moffett. The two quarreled over certain elements of Bureau policy, and King was replaced by Commander John Henry Towers and transferred to command of Naval Station Norfolk.[48]

Aircraft carrier captain

On 20 June 1930, King became captain of the aircraft carrier USS Lexington—then one of the largest aircraft carriers in the world—which he commanded for the next two years.[49] When not on duty, he enjoyed drinking, partying and socializing with his junior officers. He ignored complaints that some of his officers rented a secluded farmhouse where prohibition and blue laws were flouted. He enjoyed the company of women and had many affairs. Women avoided sitting next to him at dinner parties if they did not want to be groped under the table. King once told a friend: "You ought to be very suspicious of anyone who won't take a drink or doesn't like women."[50]

In 1932, King attended the Naval War College. In a war college thesis entitled "The Influence of National Policy on Strategy", King identified Great Britain and Japan as the United States's most likely adversaries.[51] He expounded on the theory that America's weakness was representative democracy:

Historically, despite Washington's (and others') experienced and cogent advice to make due preparations for war, it is traditional and habitual for us to be inadequately prepared. This is the combined result of a number of factors, the character of which is only indicated: democracy, which tends to make everyone believe that he knows it all; the preponderance (inherent in democracy) of people whose real interest is in their own welfare as individuals; the glorification of our own victories in war and the corresponding ignorance of our defeats (and disgraces) and of their basic causes; the inability of the average individual (the man in the street) to understand the cause and effect not only in foreign but domestic affairs, as well as his lack of interest in such matters. Added to these elements is the manner in which our representative (republican) form of government has developed as to put a premium on mediocrity and to emphasize the defects of the electorate already mentioned.[51]

Chief of the Bureau of Aviation

Aware that Moffett was due to retire in mid-1933, King lobbied for his job. In this he was aided by Winder R. Harris, the managing editor of The Virginian-Pilot newspaper, and Senator Harry F. Byrd, who wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt on his behalf. The position became available earlier than expected after Moffett died in the crash of the airship USS Akron on 4 April 1933. The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral William V. Pratt, listed King as his fourth choice, after Rear Admirals Joseph M. Reeves, Harry E. Yarnell and John Halligan Jr., but Claude A. Swanson, the new Secretary of the Navy, recommended King, having been impressed by work in the salvage of the S-51 and S-4. King became Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, and was promoted to rear admiral on 26 April 1933.[52][53]

As bureau chief, King worked closely with Leahy, who was now the chief of the Bureau of Navigation, to increase the number of naval aviators. Together they established the Aviation Cadet Training Program to recruit college graduates as aviators. His relationship with the CNO, Admiral William H. Standley, who sought to assert the power of the CNO over the bureau chiefs, was more tempestuous. With the help of Leahy and Swanson, King managed to block Standley's proposals.[54][55][56]

King appeared before a subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee, chaired by Congressman William A. Ayres, where he was questioned about the Bureau of Aeronautics's contractual arrangements with Pratt and Whitney. Although warned by his staff that an forthright answer could strain the relationship with the sole supplier of certain engines the Navy needed, King confirmed to the committee that Pratt and Whitney was making profits of up to 45 percent. As a result, the 1934 Vinson–Trammell Act contained a provision limiting profits on government aviation contracts to 10 percent.[57]

Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force

In 1936, there were only two seagoing aviation flag billets: Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force, a vice admiral who commanded the Navy's aircraft carriers, and Commander, Aircraft, Base Force, a rear admiral who commanded the seaplane squadrons. King hoped to get the former assignment, but this was opposed by Standley, and at the conclusion of his term as bureau chief in 1936, King became Commander, Aircraft, Base Force, at Naval Air Station North Island, California.[58][59] He survived the crash of his Douglas XP3D transport on 8 February 1937.[60]

Leahy succeeded Standley as CNO on 1 January 1937.[61] King was promoted to vice admiral on 29 January 1938 on becoming Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force – at the time one of only three vice admiral billets in the U.S. Navy.[62] He flew his flag on the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga. Among his accomplishments was to corroborate Yarnell's 1932 war game findings in 1938 by staging his own successful simulated naval air raid on Pearl Harbor, showing that the base was dangerously vulnerable to aerial attack, although he was taken no more seriously until 7 December 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the base.[63][64]

World War II

General Board

King hoped to be appointed CNO or Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (CINCUS), but on 1 July 1939, he reverted to his permanent rank of rear admiral and was posted to the General Board, an elephants' graveyard where senior officers spent the time remaining before retirement. A series of extraordinary events would alter this outcome.[65][66] In March, April and May 1940, King accompanied the Secretary of the Navy, Charles Edison, Edison's naval aide, Captain Morton L. Deyo, and Edison's friend Arthur Walsh on a six-week tour of naval bases in the Pacific. En route they stopped in Hollywood to preview Edison, the Man, a biographical film about the life of Edison's father starring Spencer Tracy. "I understand", Walsh told King, referring to a popular myth, "that you shave with a blowtorch." King replied that this was an exaggeration.[67][68] Walsh liked the story so much he told everyone he met, and eventually had Tiffany & Co. make a scale model of a blowtorch, which he presented to King.[69]

When they returned to Washington, D.C., Edison gave King a special assignment: to improve the anti-aircraft defenses of the fleet. Experiments with radio-controlled drones making passes at ships in February 1939 had shown that they were very difficult to shoot down. Aircraft were flying faster and carrying bigger bombs, posing a greater threat to the fleet, which would soon be confirmed in combat.[70] King looked over the plans for each type of ship and made recommendations as to what kind of guns could be installed, where they should be located, and what should be removed to make way for them. He prepared a request for $300 million to carry out the program. Edison was impressed, and wrote to Roosevelt, recommending that King be appointed CINCUS, but Roosevelt did not make the appointment, influenced by King's heavy drinking.[71]

Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet

The CNO, Admiral Harold R. Stark, considered King's talent for command was being wasted on the general board. In September 1940, Stark summoned King to his office, along with the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, Rear Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, and offered King the command of the Atlantic Squadron. Nimitz explained that while King had been a vice admiral in his last seagoing command, he would only be a rear admiral for this one. King replied that he did not care, and accepted the position. However, his assumption of command was delayed for a month by a hernia operation, and then several more weeks while he accompanied Edison's successor, Frank Knox, on another inspection tour, this time of bases in the Atlantic.[71]

On 17 December 1940, King raised his flag as Commander, Patrol Force (as the Atlantic Squadron had been renamed on 1 November) on the battleship USS Texas in Norfolk, Virginia. When he examined the war plan in the safe, he found it was for a war with Mexico.[72] His first order, issued three days later, was to place the Patrol Force on a war footing. He astonished subordinates by stating that the United States was already at war with Germany.[73] In January 1941 King issued Atlantic Fleet directive CINCLANT Serial 053, encouraging officers to delegate and avoid micromanagement, which is still cited widely in today's armed forces.[74][75] The Patrol Force was designated the Atlantic Fleet on 1 February 1941. King was promoted to admiral and became the Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANT).[76] Formerly a heavy drinker, he gave up hard liquor for the duration of the war in March 1941.[77]

In April 1941, King was summoned to Hyde Park, New York, where Roosevelt informed him of an upcoming conference with the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Winston Churchill, at Argentia. He went to Hyde Park again in July to make further arrangements. King found the old Texas to be unsuitable as a flagship, and on 24 April he switched to the cruiser USS Augusta once it had completed an overhaul.[78][79] So it was that in August it was the Augusta that took Roosevelt to the Atlantic Conference, where King and British Admiral Sir Percy Noble worked out the details for the United States Navy escorting convoys halfway across the Atlantic.[80]

Rather than risk a conflict with the United States on the eve of the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Germans withdrew their submarines from the western Atlantic. This emboldened Roosevelt to take further steps.[81] He declared a National Emergency on 27 May.[82] On 19 July, King issued orders creating Task Force 1, with the mission of escorting convoys to Iceland, which had been occupied by the U.S. Marines. Nominally, the convoys were American, but ships of any nationality were free to join.[83] From 1 September, convoys were escorted to a mid-ocean meeting point, where they met escorts from the Royal Navy and Royal Canadian Navy. The United States was now engaged in an undeclared war, although they were still restricted by the Neutrality Acts of the 1930s.[84] On 31 October, the destroyer USS Reuben James became the first U.S. warship to be sunk by a German U-boat.[85] In response to this and other incidents, Congress amended the Neutrality Acts in November, allowing merchant ships to be armed and to deliver goods to British ports.[86]

Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet

Staff

With the United States declaration of war on Germany on 11 December, the Atlantic Fleet was officially at war. On 20 December, King became CINCUS. Ten days later he hoisted his flag on USS Vixen and was succeeded as CINCLANT by Admiral Royal E. Ingersoll.[87][88] Nimitz became the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet on the same day.[89] Legend has it that King said: "When they get into trouble, they call for the sons-of-bitches." John L. McCrea, Roosevelt's naval aide, asked King if he actually had said it. King replied that he had not, but would have if he had thought of it.[90][91] The abbreviation CINCUS (pronounced "sink-us") seemed inappropriate after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and on 12 March 1942 King officially changed it to COMINCH.[89]

Stark was reluctant to part with Ingersoll as his chief of staff, but King insisted that he was needed as CINCLANT. He offered Rear Admiral Russell Willson, the Superintendent of the Naval Academy, and Rear Admiral Frederick J. Horne, from the General Board, as replacements. Stark chose Horne, and King then took Willson as his own chief of staff. Rear Admiral Richard S. Edwards, who had served King as Commander, Submarines, Atlantic Fleet, became his deputy chief of staff. For assistant chiefs of staff, King selected Rear Admirals Richmond K. Turner and Willis A. Lee.[92][93]

King did not get along with Willson; their personalities were too different, and later admitted that he had made a mistake in appointing him. King had Willson retired in August 1942 due to heart conduction and replaced him with Edwards.[94] When Turner went to the South Pacific for the Guadalcanal campaign, he was succeeded by Rear Admiral Charles M. Cooke Jr..[92][93] Although he was now based at the Navy Department in Washington, D.C., King wanted to be able to put to sea himself at any time. For his flagship, he selected the SS Delphine, a luxury yacht formerly owned by the family of Horace Dodge, which King renamed USS Dauntless. King lived on board Dauntless, which spent most of the war at anchor at the Washington Navy Yard.[95]

Joint Chiefs of Staff

When the American chiefs of staff, which included King and Stark, met with the British Chiefs of Staff Committee at the Arcadia Conference in Washington, D.C., from 24 December 1941 to 14 January 1942,[96] they agreed to merge their organizations to form the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS), which held its first meeting in Washington, D.C., on 23 January 1942. To parallel the British chiefs, the Americans formed the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), which held its first meeting on 9 February 1942. The Joint Chiefs of Staff initially consisted of Stark, King, General George C. Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, and Lieutenant General Henry H. Arnold, the Chief of the United States Army Air Corps. In his role as a member of the CCS and JCS, King became engaged in the formulation of grand strategy, which came to occupy the majority of his time.[97][98]

Roosevelt's Executive Order 8984 made COMINCH the commander of the operational forces of the navy, and "directly responsible, under the general direction of the Secretary of the Navy, to the President of the United States."[99] There was considerable overlap between the roles of COMINCH and CNO,[100] and on Stark's advice,[101] Roosevelt combined the duties of the two with Executive Order 9096.[102] On 26 March, King succeeded Stark as CNO, becoming the only officer to hold this combined command. On the same date, Horne became the Vice Chief of Naval Operations.[87][103] Although King was both COMINCH and CNO, the two offices remained separate and distinct.[104] Stark became Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Europe.[105] Edwards, Cooke and Horne remained with King for the duration of the war, but more junior officers were brought in for periods of up to a year and then returned to sea duty.[92][93] When King turned 64 on 23 November 1942, King wrote Roosevelt to say he had reached mandatory retirement age. Roosevelt replied with a note saying: "So what, old top? I may send you a birthday present." (The present was a framed photograph.)[106]

Stark left the JCS in March 1942 when King succeeded him as CNO, reducing its membership to three until July 1942. Marshall advocated a joint general staff, but in the face of opposition from King, he backed down on the idea of an executive head of the services. Instead, Marshall pressed for a senior officer to act as a JCS spokesperson and a liaison between the JCS and the President. He nominated Leahy for the post, hoping that a naval officer would be more acceptable to King. King remained opposed, but Roosevelt was convinced of the merits of the proposal. On 21 July 1942, Leahy was appointed Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy and became the fourth member of the JCS. As the senior officer, Leahy chaired its meetings, but he did not exercise any command authority.[107][108] King and Marshall retained their direct access to the President. King had thirty-two official meetings with Roosevelt at the White House in 1942, but only eight in 1943, nine in 1944 and just one in 1945.[109]

Civil-Naval relations

Roosevelt was not above micromanaging the navy. For example, in early 1942 he sent explicit instructions to Admiral Thomas C. Hart, the commander of the Asiatic Fleet, detailing how he wanted surveillance patrols run.[110] Roosevelt granted Marshall broad authority to reorganize the War Department, but King's authority was more constrained. King, acting on a suggestion from Roosevelt that he "streamline" the Navy Department, ordered a restructure on 28 May. It was opposed by Knox and the Under Secretary of the Navy, James V. Forrestal, who saw it a challenge to their authority, and by the bureau chiefs, who feared a loss of their autonomy. Most importantly, it was opposed by Roosevelt, who, on 12 June, ordered Knox to cancel everything King had done.[111][112] Roosevelt did assent to King's proposal to create the post of Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Aviation (DCNO (Air)), but in a note to Knox in August 1943 he wrote: "Tell Ernie once more: No reorganizing of the Navy Dept. set-up during the war. Let's win it first."[113][114]

With King reporting directly to Roosevelt and only under his "general supervision", Knox saw King as a threat to his authority. He attempted to remove King in 1942 by suggesting he assume command in the Pacific as COMINCH, but this was not possible because as a member of the JCS, King had to remain in Washington, D.C. The following year, Knox tried to have Horne, who dealt with most of the CNO work like preparing budgets and appearing before Congress, appointed as CNO. This too failed, as it required executive action by Roosevelt, and King elevated Edwards over Horne's head to the new position of deputy COMINCH and deputy CNO on 1 October 1944. Cooke replaced Edwards as chief of staff to the CNO.[111][115] Knox died from a heart attack on 28 April 1944, and Roosevelt nominated Forrestal as his replacement. As Under Secretary of the Navy, Forrestal was familiar with naval issues, and he had a good track record managing the navy's procurement program. He was unanimously confirmed by the Senate, but King and Forrestal clashed.[116]

Ships and manpower

The Navy had always thought in terms of ships, but more were on order than the Navy had personnel to crew them.[117] The fleet grew faster than expected because plans assumed losses on the scale of 1942, but in fact they were much fewer.[118] With the Navy now dominated by aviators and submariners, the easiest target for ship cancellations were the battleships. In May 1942, King had indefinitely deferred construction of five battleships, including all the Montana class, in favor of more aircraft carriers and cruisers. King had opposed construction of the Montana class while he was on the General Board on the grounds that they were too big to fit through the Panama Canal.[119]

Aircraft carriers were another matter; King strongly opposed Roosevelt's proposal in August 1942 to defer the Midway-class aircraft carriers on the grounds that they would consume too many resources and were unlikely to be completed until after the war. Eventually Roosevelt authorized them, but his forecast proved correct.[119] However King gave way to Roosevelt on the issue of escort carriers; while he believed that nothing smaller than the Essex-class aircraft carrier would be useful in the Pacific war, he accepted Roosevelt's argument that it was important to get new aircraft carriers in commission quickly.[120] In 1943, with the war against the U-boats being won, King canceled 200 of the 1,000 destroyer escorts on order, but backed off canceling another 200 when the Bureau of Ships protested.[121]

By March 1944, it was estimated that the Navy would reach its manpower ceiling by August, and would require 340,000 more sailors by the end of the year for ships under construction, which included nine Essex-class aircraft carriers.[122] On 2 July, King asked the Joint Chiefs to approve an increase of 390,000 men. The Army did not object, as it was more than 300,000 over its own personnel ceiling, and needed assault shipping for the Philippines campaign. It was noted that this would exacerbate the national labor shortage and adversely affect the munitions industry, and drastic measures might be required if the Army ran into more manpower difficulties, as indeed occurred.[123]

War in the Atlantic

When war was declared on Germany, an attack on coastal shipping by U-boats was anticipated, as this was what had happened in World War I. On 12 December 1941, German U-boat commander, Vizeadmiral Karl Dönitz, ordered an attack, codenamed Operation Paukenschlag ("Roll of the drums" or "drumbeat").[124] The following day, King issued a warning to all Atlantic commands of an impending German U-boat attack.[125] This did not occur immediately, because the U-boats had been withdrawn from the Western Atlantic and priority was accorded to operations in the Mediterranean. Some use was made of this respite to lay a defensive naval minefield and erect protective harbor anti-submarine nets and booms.[124] Only the long-range Type IX and some Type VII submarines could reach the Western Atlantic, so only six to eight U-boats were on station of the East coast between January and June 1942.[125]

The carnage began on 12 January, when a British steamer was sunk 300 nautical miles (560 km; 350 mi) off Cape Cod by U-123. By the end of the month, U-boats had sunk thirteen ships totaling 95,000 gross register tons (270,000 m3). Few of the merchant ships were armed and those that were, were no match for the U-boats. Each U-boat carried fourteen torpedoes, including some of the new electric model, which left no air bubbles in its wake, and had a deck gun capable of sinking many merchant ships.[126] There was no seaboard blackout, as this was a politically sensitive issue—coastal cities resisted, citing the loss of tourism revenue.[127] Waterfront lights and signs switched off on 18 April 1942, and the Army declared a blackout of coastal cities on 18 May. The Germans had broken the American and British codes and sometimes lay in wait.[126] Meanwhile, the German Navy added an extra wheel to its Enigma machines in April and the Allies lost the ability to decrypt its signals for ten months.[128]

The first requirement of an effective anti-submarine campaign was anti-submarine escorts. In 1940, when he was a member of the General Board, King had recommended copying the 327-foot (100 m) Treasury-class cutter as an anti-submarine escort. As commander-in-chief of the Atlantic Fleet he had pressed Stark to secure such craft, but Stark replied that the President did not approve. Roosevelt, who had been involved in the development of the submarine chaser, a much smaller vessel, during World War I, believed that small craft would be sufficient to deal with the U-boats, and that they could be acquired at the last minute, so there was no need to interfere with the capital-ship building program. While acknowledging that small craft like submarine chasers had their uses, King pointed out that escort duty required vessels that could cope with rough weather and had sufficient crewmen to mount round-the-clock watches.[129]

The ideal escort was the destroyer, but were required for escorting troopships and trans-Atlantic convoys, and protecting the warships of the Atlantic and Pacific fleets. They also had features not required for convoy escort duty that slowed their rate of production. A cut-down version of a destroyer, known as a destroyer escort, was developed specifically for anti-submarine warfare that could be produced in large numbers. The first of these was ordered in July 1941, and King asked for a thousand of them in June 1942, but higher priorities for landing craft resulted in the first of them not being delivered until April 1943.[130][129]

As escorts became available, a system of coastal convoys could be instituted. King convened a board with representatives from COMINCH, CINCLANT, and the Sea Frontiers to devise a comprehensive system. "Escort is not just one way of handling the submarine menace," King opined, "it is the only way that gives any promise of success. The so-called hunting and patrol operations have time and again proved futile."[131] The board reported on 27 March. In May 1942, King established a day and night interlocking convoy system running from Newport, Rhode Island, to Key West, Florida, and by August 1942, the submarine threat to shipping in US coastal waters had been contained. The same effect occurred when convoys were extended to the Caribbean.[132]

As time went on, King gradually assumed more control over the anti-submarine campaign. He designated Edwards as anti-submarine coordinator, and in May 1942 he had the Convoy and Routing Section transferred from the office of the CNO to the office of the COMINCH. An anti-submarine warfare unit was established as part of the COMINCH staff. This led to the establishment of the Anti-Submarine Warfare Operations Research Group, which conducted operations research in cooperation with the scientists of the National Defense Research Committee.[116] He also established, on the advice of Royal Navy officers, an operational intelligence center (OIC) that tracked U-boat movements and provided warning to merchant shipping.[133] On 20 May 1943, he created the Tenth Fleet, under his own command, to coordinate the anti-submarine campaign.[134] Between July 1942 and May 1943, German and Italian submarines sank 780 merchant ships totaling 4.5 million gross register tons (13,000,000 m3), but ships were being built faster than the submarines could sink them.[135] In the same period, a monthly average of 13 submarines were sunk, compared to 18 to 23 being built each month.[136]

Another answer to the U-Boat menace was long-range maritime patrol aircraft. This was complicated by inter-service squabbling over command and control. The aircraft belonged to the Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command, but the mission was the Navy's, and there were differences in doctrine between the two. Arnold resisted assigning aircraft to operational control of the sea frontier commanders, and King rejected a proposal to place all air assets, Army and Navy, under the Army Air Forces. Instead, Marshall agreed to transfer the long-range B-24 Liberator aircraft to the Navy. Arnold and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson were apprehensive about this, and sought reassurances that the Navy was not seeking a role in strategic bombing. An acceptable agreement was negotiated, and the aircraft were transferred on 1 September 1943, except for some in the UK, which followed in November.[137]

King accorded warship construction priority over merchant shipbuilding. The JCS approved 2.8 million gross register tons (7,900,000 m3) of new Liberty ships for 1943 on condition that it did not interfere with warship construction. The merchant shipbuilding program only went ahead because industrial capacity rose to the point where this became possible. The JCS rejected further increases in merchant ships because steel was in short supply. There were also critical shortages of rubber, which the Army needed for truck tires and tank tracks, and high-octane aviation gasoline, which the Army Air Forces needed for its planes. King concurred with the War Production Board's plans to give priority to synthetic rubber production, but rejected proposals to increase the priority of aviation gasoline production on the grounds that it would interfere with the destroyer escort program.[138]

War in Europe

In keeping with the agreed "Germany first" strategy, the Joint Chiefs proposed to build up a force of 48 divisions in the UK (Operation Bolero) for a landing in France in 1943 (Operation Roundup). The U.S. Army planners realized that the Western Allies did not have the resources to challenge Germany on land and most of the fighting would have to be done by the Soviet Union. Keeping the Soviet Union in the war was therefore crucial. If the USSR looked like it was about to collapse, an emergency landing would be made in France in 1942 (Operation Sledgehammer).[139]

The British chiefs rejected Sledgehammer and instead proposed an invasion of French North Africa (Operation Gymnast).[140] The U.S. Army planners, led by Major General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Chief of the War Plans Division,[141] concluded that the next best way to help the Soviets was an offensive against Japan in the Pacific, which would prevent the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria from attacking the Soviet Union in Siberia.[139] King concurred with this proposal; he did not see any value in leaving resources idle in the Atlantic when they could be utilized in the Pacific, especially when "it was doubtful when—if ever—the British would consent to a cross-Channel operation".[142] Roosevelt did not agree, and he ordered the Joint Chiefs to carry out Operation Gymnast.[143]

Landing ships and landing craft enjoyed the highest priority for construction in 1942,[144] but after the abandonment of Sledgehammer and Roundup, King diverted many of them to the Pacific. At the First Quebec Conference in September 1943, King promised to provide 110 LST, 58 LCI, 146 LCT, 250 LCM and 470 LCVP for Operation Overlord, the invasion of France in 1944. When the Overlord plan was enlarged to five divisions in early 1944, this was not enough. There was also a discrepancy between British and American calculations of the capacity of the available landing ships and landing craft.[145]

Marshall sent Major General John E. Hull and King sent Cooke to Europe, where they met with Rear Admirals Alan G. Kirk, the commander of the Western Naval Task Force (Task Force 122) and John L. Hall Jr., the commander of the XI Amphibious Force. Together they resolved the issues surrounding loading capacity and landing craft availability, and Eisenhower postponed Operation Anvil, the landing in Southern France, allowing more amphibious vessels to be released from the Mediterranean. Ultimately, King provided 168 LST, 124 LCI, 247 LCT, 216 LCM and 1,089 LCVP for Overlord. Hall took the opportunity to lobby for more naval gunfire support ships. King had assumed that the Royal Navy would provide this, but the Royal Navy was keeping a strong force in reserve with the Home Fleet in case the German Navy sortied. King sent the battleships USS Nevada, Texas and Arkansas and a squadron of destroyers.[145]

War in the Pacific

King took the lead in developing a strategy for the war in the Pacific. Following Japan's defeat at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, King proposed an operation in the Solomon Islands. After some discussion of command arrangements, Marshall suggested moving the boundary of South West Pacific Area to transfer the southern Solomons to the South Pacific Area. The two theater commanders, General Douglas MacArthur and Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, expressed doubts about the operation, but King instructed Nimitz to proceed.[146] The Marines successfully landed on Guadalcanal on 7 August, but on the night of 8/9 August the U.S. and Royal Australian Navy suffered a severe defeat in the Battle of Savo Island, losing four cruisers.[147] King tried to suppress the news of the disaster.[148]

As the situation in the South Pacific went from bad to worse, King attempted to get Marshall and Arnold to provide additional resources, but their priority was Operation Torch, the landing in North West Africa.[149] In the end, Roosevelt ordered the Joint Chiefs to hold Guadalcanal.[150] On 16 October, King assented to Nimitz's request to relieve Ghormley, and replace him with Vice Admiral William F. Halsey. More aggressive leadership brought results, but at a cost: in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October, the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise was damaged and the USS Hornet was sunk.[151] The tide gradually turned in November as reinforcements arrived, although the fighting on Guadalcanal continued until 8 February 1943.[152]

On behalf of the JCS, King took the lead in formulating strategy for the Pacific war. In March 1943, he called representatives from the South Pacific Area, Central Pacific Area and Southwest Pacific Area together for the Pacific Military Conference, which decided on the tasks for 1943.[153] On 25 September 1943, King traveled to Pearl Harbor for his first meeting with Nimitz there. First item on the agenda was Operation Galvanic, the campaign to capture Tarawa Atoll and Nauru. Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, the commander of the Fifth Fleet, surprised King with a paper from the commander of the V Amphibious Corps, Major General Holland M. Smith, which argued that Nauru was too well-defended. Smith and Spruance recommended seizing Makin Atoll instead. King was reluctant to do so but eventually agreed, and secured the concurrence of the other Joint Chiefs.[154]

King also met with Rear Admiral Charles A. Lockwood, the commander of the Pacific Fleet's submarines. Lockwood told King about problems the submariners were having with the Mark 14 torpedo, which had both magnetic and contact exploders. Tests that he had recently conducted had confirmed reports from the submarine skippers that neither exploder worked properly, and he secured King's permission to modify the torpedoes at Pearl Harbor rather than wait for the Bureau of Ordnance to provide fixes. King raised the prospect of promoting Lockwood to vice admiral. When Nimitz did not give Lockwood a spot promotion, King had Lockwood promoted when he returned to Washington, D.C. King had been impressed by the German G7e electric torpedoes, some of which had been salvaged after running ashore, and prompted the Bureau of Ordnance to develop an electric torpedo. The result was the Mark 18 torpedo, but it was beset by many developmental and production problems.[155][156]

After the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign, King then considered the capture of the Mariana Islands, Palau and Truk, with the ultimate objective being China, which was holding down the major part of the Japanese Army, and from whence King anticipated that the final assault on Japan would be launched. King pressed for the capture of the Mariana Islands, which could serve both as a naval base astride Japanese communications and as a base for aerial bombardment of the Japanese home islands by the Army's long-range Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers.[157][158] A major strategy issue in late 1944 was whether to follow the capture of the Marianas with an assault on Luzon or Formosa.[159] King favored Formosa, but he was eventually convinced that Nimitz and MacArthur's plan to take Luzon followed by Okinawa was preferable.[160]

King once complained that the Pacific deserved 30 percent of Allied resources but was getting only 15 percent.[161] When, at the Cairo Conference in 1943, he was accused by British Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke of favoring the Pacific war, the argument became heated. The combative Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell wrote: "Brooke got nasty, and King got good and sore. King almost climbed over the table at Brooke. God, he was mad. I wished he had socked him."[162] One of King's daughters was quoted as saying of her father: "he is the most even tempered person in the United States Navy. He is always in a rage."[163]

Relations with the British

The deployment of a British fleet to the Pacific was a political matter. The measure was forced on Churchill by the British Chiefs of Staff, not merely to re-establish British presence in the region, but to mitigate any impression in the US that the British were doing nothing to help defeat Japan. At the Octagon Conference in Quebec in September 1944, King was adamant that naval operations against Japan remain American, and resisted a British naval presence in the Pacific, leading some historians to level accusations of Anglophobia and wanting to keep the British from grabbing some of the glory of the defeat of Japan in the Pacific. The U.S. Navy indeed had an old institutional rivalry with the Royal Navy, and King was a product of that institution.[164]

However, King cited the logistical and technical difficulties in maintaining British naval forces in the Pacific, details that he was intimately familiar with as a former aircraft carrier captain. The Royal Navy was designed for short-range operations in a cool climate; in the Pacific it would require its own ammunition and refrigerated cargo ships. Even American-supplied aircraft could not be used unmodified.[165] Roosevelt and Leahy overruled him, and the Joint Chiefs accepted the British offer provided that the fleet would be fully self-supporting.[166] Despite King's reservations, the British Pacific Fleet acquitted itself well against Japan in the last months of the war. King's concerns about logistics were valid, and the British Pacific Fleet was not fully self-supporting.[167]

Like most Americans, King was opposed to operations that would assist the British, French and Dutch in reclaiming their pre-war overseas possessions in South East Asia.[168] Although frequently described as Anglophobic, King was proud of his British ancestry, enjoyed his visits to the United Kingdom and established good relations with many of his British colleagues.[164][169] When a Royal Air Force officer complained that King was anti-British, Field Marshal Sir John Dill said King was pro-American rather than anti-British. When Dill was in hospital, King visited him every day.[170]

When Admiral Sir James Somerville was placed in charge of the British naval delegation in Washington, D.C., in October 1944 he managed—to the surprise of almost everyone—to get on very well with the notoriously abrasive and anti-British King.[171] General Hastings Ismay described King as:

... tough as nails and carried himself as stiffly as a poker. He was blunt and stand-offish, almost to the point of rudeness. At the start, he was intolerant and suspicious of all things British, especially the Royal Navy; but he was almost equally intolerant and suspicious of the American Army. War against Japan was the problem to which he had devoted the study of a lifetime, and he resented the idea of American resources being used for any other purpose than to destroy the Japanese. He mistrusted Churchill's powers of advocacy, and was apprehensive that he would wheedle President Roosevelt into neglecting the war in the Pacific ... As we all got to know each other better, King mellowed and became much more friendly. The last time I saw him was at a big official dinner in Potsdam in July 1945 when, to my amazement, he proposed my health in very flattering terms. I was as proud as a subaltern getting his first mention in despatches.[172]

Retirement and death

On 14 December 1944, Congress passed legislation creating the five-star ranks of fleet admiral and general of the army. Each service was authorized to have up to four officers of five-star rank. Leahy was promoted to fleet admiral on 15 December, and Marshall, King, MacArthur, Nimitz, Eisenhower and Arnold followed on successive days. When King was promoted on 17 December, he became the second of four men in the U.S. Navy to hold the rank of fleet admiral, and the third most senior officer in the U.S. military.[173]

President Harry S. Truman's Executive Order 9635 of 29 September 1945 revoked Executive Orders 8984 and 9096 and restored the primacy of the Secretary of the Navy and the CNO. The office of COMINCH was abolished on 10 October.[174][175] It was King's wish that Nimitz succeed him as CNO, but Forrestal wanted Edwards. King forced the issue by writing to Truman via Forrestal. Truman agreed to Nimitz's appointment, Forrestal asserted his authority by limiting Nimitz's tenure to two years instead of the usual four, and making the change of command earlier than King wanted.[176]

Although King left active duty on 15 December, he officially remained in the Navy, as five-star officers were given active duty pay for life. The pay of all flag officers was the same until 1955, when Congress raised that of vice admirals and admirals, but that of five-star officers remained the same. Nor was it lifted during subsequent pay raises, and after they died the widows of five-star officers received a pension based on the rank of rear admiral.[177]

In retirement, King lived in Washington, D.C. He was active in his early post-retirement, serving as president of the Naval Historical Foundation from 1946 to 1949,[178] and he wrote the foreword to and assisted in the writing of Battle Stations! Your Navy In Action, a photographic history book depicting the U.S. Navy's operations in World War II that was published in 1946.[179] With Walter Muir Whitehill, he co-wrote an autobiography (in the third person), Fleet Admiral King: A Naval Record, which was published in 1952.[176]

King suffered a debilitating stroke in August 1947, and subsequent ill-health ultimately forced him to stay in naval hospitals at Bethesda, Maryland, and at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine.[180][181] King died of a heart attack in Kittery on 25 June 1956, at the age of 77. His body was flown to Washington, D.C., and after lying in state at the National Cathedral, King was buried in the United States Naval Academy Cemetery at Annapolis, Maryland. His wife Mattie was buried beside him in 1969.[182][183] His papers are in the Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy.[184]

Dates of rank

- United States Naval Academy naval cadet – June 1901

| Ensign | Lieutenant (junior grade) | Lieutenant | Lieutenant commander | Commander | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 | O-5 | O-6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 June 1903 | Never Held | 7 June 1906 | 1 July 1913 | 1 July 1917 | 21 September 1918 |

| Rear admiral | Vice admiral | Admiral | Fleet admiral |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-8 | O-9 | O-10 | Special Grade |

|

|

|

|

| 26 April 1933 | 29 January 1938 | 1 February 1941 | 17 December 1944 |

King never held the rank of lieutenant (junior grade) although, for administrative reasons, his service record annotates his promotion to both lieutenant (junior grade) and lieutenant on the same day.

Awards and decorations

| |||

Navy Cross citation

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Captain Ernest Joseph King, United States Navy, for distinguished service in the line of his profession during World War I, as Assistant Chief of Staff of the Atlantic Fleet during World War I.[47]

Navy Distinguished Service Medal citation (first award)

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Distinguished Service Medal to Captain Ernest Joseph King, United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service in a position of great responsibility to the Government of the United States, as Officer in charge of the salvaging of the U.S.S. S-51, from 16 October 1925 to 8 July 1926.[47]

Navy Distinguished Service Medal citation (second award)

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting a Gold Star in lieu of a Second Award of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal to Captain Ernest Joseph King, United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service in a position of great responsibility to the Government of the United States as Commanding Officer of the Salvage Force entrusted with the raising of the U.S.S. S-4, sunk as a result of a collision off Provincetown, Massachusetts, 17 December 1927. Largely through his untiring energy, efficient administration and judicious decisions this most difficult task, under extremely adverse conditions, was brought to a prompt and successful conclusion.[47]

Navy Distinguished Service Medal citation (third award)

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting a Second Gold Star in lieu of a Third Award of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal to Fleet Admiral Ernest Joseph King, United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service in a position of great responsibility to the Government of the United States as Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet from 20 December 1941, and concurrently as Chief of Naval Operations from 18 March 1942 to 10 October 1945. During the above periods, Fleet Admiral King, in his dual capacity, exercised complete military control of the naval forces of the United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard and directed all activities of these forces in conjunction with the U.S. Army and our Allies to bring victory to the United States. As the United States Naval Member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Combined Chiefs of Staff, he coordinated the naval strength of this country with all agencies of the United States and of the Allied Nations, and with exceptional vision, driving energy, and uncompromising devotion to duty, he fulfilled his tremendous responsibility of command and direction of the greatest naval force the world has ever seen and the simultaneous expansion of all naval facilities in the prosecution of the war. With extraordinary foresight, sound judgment, and brilliant strategic genius, he exercised a guiding influence in the Allied strategy of victory. Analyzing with astute military acumen the multiple complexity of large-scale combined operations and the paramount importance of amphibious warfare, Fleet Admiral King exercised a guiding influence in the formation of all operational and logistic plans and achieved complete coordination between the U.S. Navy and all Allied military and naval forces. His outstanding qualities of leadership throughout the greatest period of crisis in the history of our country were an inspiration to the forces under his command and to all associated with him.[47]

Foreign awards

King was also the recipient of several foreign awards and decorations (shown in order of acceptance and if more than one award for a country, placed in order of precedence):[185]

| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom) 1945 | |

| Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur (France) 1945 | |

| Grand Cross of the Order of George I (Greece) 1946 | |

| Knight Grand Cross with Swords of the Order of Orange-Nassau (Netherlands) 1948 | |

| Knight of the Grand Cross of the Military Order of Italy 1948 | |

| Order of Naval Merit (Brazil), Grand Officer 1943 | |

| Estrella Abdon Calderon (Ecuador) 1943 | |

| Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown with palm (1948) | |

| Commander of the Order of Vasco Núñez de Balboa (Panama) 1929 | |

| Officer of the Order of the Crown of Italy 1933 | |

| Order of Naval Merit (Cuba) 1943 | |

| Order of the Sacred Tripod (China) 1945 | |

| Croix de guerre (France) (1944) | |

| Croix de Guerre (Belgium) (1948) |

Legacy

- The guided missile destroyer USS King was named in his honor.[186]

- Two public schools in his hometown of Lorain, Ohio, have been named after him: (Admiral King High School) until it was merged with the city's other public high school to form Lorain High School in 2010, and Admiral King Elementary School.[187]

- In 1956, schools located on the U.S. Naval Bases and Air Stations were given names of U.S. heroes of the past. E.J. King High School, the Department of Defense high school on Sasebo Naval Base, in Japan, is named for him.[188]

- The dining hall at the U.S. Naval Academy, King Hall, is named after him.[189]

- The auditorium at the Naval Postgraduate School, King Hall, is named after him.[190]

- Recognizing King's great personal and professional interest in maritime history, the Secretary of the Navy named in his honor an academic chair at the Naval War College to be held with the title of the Ernest J. King Professor of Maritime History.[191]

- One of the two major living quarters at the Officer Training Command Newport, Rhode Island, is named King Hall in his honor.[192]

- King was portrayed by Tyler McVey in The Gallant Hours (1960),[193] Russell Johnson in MacArthur (1977),[194] John Dehner in War and Remembrance (1988),[195] and Mark Rolston in Midway (2019).[196]

Notes

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 11–13.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 14.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2009, p. 336.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 7.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 8–12.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 18–23.

- ^ a b King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 30–33.

- ^ a b c Buell 1995, pp. 16–20.

- ^ a b c d e Buell 1995, pp. xxii–xxv.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 45–47.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 50–59.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 23–25.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 12.

- ^ "Engagement Announced". The Baltimore Sun. 9 January 1903. Archived from the original on 10 August 2024. Retrieved 7 May 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 26.

- ^ "Marriage announcement of Florence Beverly Egerton". The Baltimore Sun. 27 March 1901. p. 7. Archived from the original on 10 August 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Borneman 2012, p. 69.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 64.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 37.

- ^ a b Buell 1995, pp. 26–28.

- ^ King 1909, p. 129.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 35.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 38–41.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 48–51.

- ^ "Full Text Citations For Award of The Navy Cross to Members of the U.S. Navy World War I". Home of Heroes. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Young, Frank Pierce. "Pearl Harbor History: Building The Way To A Date Of Infamy". Archived from the original on 5 June 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 36, 54–55.

- ^ Kohnen 2018, pp. 137–139.

- ^ a b Buell 1995, p. 58.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. xxiv.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 67–70.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 71–72.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 187.

- ^ a b King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 75–76.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 228.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 76–78.

- ^ a b c d e "Ernest King – Recipient". Military Times. Archived from the original on 10 August 2024. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 211.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 214.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 89–92.

- ^ a b King 1932, pp. 26–27.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 240–242.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Borneman 2012, pp. 153–155.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 249.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 100.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 99–101.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 266.

- ^ Morton 1985, pp. 70–72.

- ^ "Leahy Will Direct Naval Operations". The New York Times. 11 November 1936. p. 53. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 279.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 110–113.

- ^ Reimers 2018, pp. 44–47.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 295.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. xxiv, 123.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 124.

- ^ Klug, Jonathan (16 January 2020). "Strategy While Shaving With a Blowtorch (Dusty Shelves) – War Room". U.S. Army War College. Archived from the original on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 306.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, p. 139.

- ^ a b Buell 1995, pp. 125–127.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 127–129.

- ^ Marino, James I. (23 November 2016). "Undeclared War in the Atlantic". Warfare History Network. Archived from the original on 10 August 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ "Navy Leader Development Framework" (PDF). US Navy. May 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Holmes, James (20 June 2017). "Memorandum for ACC Commanders: Leadership, Initiative, and War" (PDF). US Air Force. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Morison 1947, p. 51.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 148–149.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 329–331.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 137–139.

- ^ Morison 1947, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Heinrichs 1998, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Morison 1947, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Morison 1947, pp. 74–79.

- ^ Morison 1947, pp. 79–85.

- ^ Morison 1947, pp. 94.

- ^ Morison 1947, pp. 80.

- ^ a b Morison 1947, pp. 114–115.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, p. 353.

- ^ a b Morison 1948, p. 255.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 573.

- ^ Barlow 1998, p. 177.

- ^ a b c Morison 1947, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b c Buell 1995, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 176–178.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 157–161.

- ^ "Arcadia Conference" (PDF). Joint Chiefs of Staff. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ Stoler 2003, pp. 64–65.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 366–368.

- ^ "Executive Order 8984 – Prescribing the Duties of the Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet and the Co-operative Duties of the Chief of Naval Operations". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, p. 141.

- ^ Burtness & Ober 2013, pp. 669–670.

- ^ "Executive Order 9096 – Reorganization of the Navy Department and the Naval Service Affecting the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet". The American Presidency Project. 12 March 1942. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, p. 137.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 357–358.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, p. 142.

- ^ Stoler 2008, p. 70.

- ^ Hamilton, Thomas J. (26 July 1942). "President Praises Leahy's Vichy Role". The New York Times. p. 17. Archived from the original on 10 August 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Buell 1998, p. 171.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 242.

- ^ a b Buell 1995, pp. 235–239.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, pp. 142–143, 157, 163.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 237.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, p. 157.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, pp. 142–143, 163.

- ^ a b Buell 1995, pp. 449–451.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, p. 160.

- ^ Davidson 1996, pp. 154–157.

- ^ a b Davidson 1996, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, p. 146.

- ^ Davidson 1996, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Davidson 1996, pp. 130–134.

- ^ Davidson 1996, pp. 134–138.

- ^ a b Morison 1947, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b Offley, Ed (February 2022). "The Drumbeat Mystery". Naval History. Vol. 36, no. 1. ISSN 1042-1920. Archived from the original on 5 June 2024. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ a b Morison 1947, pp. 126–132.

- ^ Gannon 1991, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Miller, Jappert & Jackson 2023, p. 133.

- ^ a b King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 446–448.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, p. 145.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 288.

- ^ Morison 1947, pp. 255–258.

- ^ Miller, Jappert & Jackson 2023, p. 135.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 462–465.

- ^ Ross 1997, p. 49.

- ^ Morison 1947, p. 407.

- ^ King & Whitehill 1952, pp. 464–471.

- ^ Davidson 1996, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Stoler 2003, pp. 77–83.

- ^ Strange 1984, pp. 453–458.

- ^ Cline 1951, p. 84.

- ^ Morison 1957, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Stoler 2003, pp. 84–87.

- ^ Love 1980, p. 151.

- ^ a b Morison 1957, pp. 52–57.

- ^ Hayes 1982, pp. 140–149.

- ^ Hayes 1982, p. 174.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 222–224.

- ^ Hayes 1982, pp. 183–185.

- ^ Hayes 1982, p. 193.

- ^ Love 1980, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Hayes 1982, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Hayes 1982, pp. 312–314.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 411.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 412–413.

- ^ Blair 1975, pp. 275–281.

- ^ Hayes 1982, pp. 546–548.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 438–440.

- ^ Hayes 1982, p. 603.

- ^ Hayes 1982, pp. 623–624.

- ^ "H-008-5 Admiral Ernest J. King". Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 10 August 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 428.

- ^ Samuel J. Cox (July 2017). "H-008-5: Admiral Ernest J. King—Chief of Naval Operations, 1942". Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 9 July 2024. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ a b Coles 2001, pp. 105–107.

- ^ Coles 2001, pp. 120–125.

- ^ Hayes 1982, pp. 637–639.

- ^ Coles 2001, pp. 127–129.

- ^ Coles 2001, pp. 112–114.

- ^ Whitehill 1957, p. 217.

- ^ Parker 1984, p. 162.

- ^ "Sir James Somerville". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36191. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Ismay 1960, p. 253.

- ^ Borneman 2012, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Hone & Utz 2023, pp. 168–169.

- ^ "Executive Order 9635—Organization of the Navy Department and the Naval Establishment". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ a b Borneman 2012, pp. 461–462.

- ^ Buell 1995, p. 388.

- ^ "A History of the Naval Historical Foundation". Naval Historical Foundation. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Book Reviews – Battle Stations! Your Navy In Action". United States Naval Institute Proceedings. Vol. 72, no. 523. September 1946. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Buell 1995, pp. 508–509.

- ^ Whitehill 1957, p. 213.

- ^ Borneman 2012, pp. 463–464.

- ^ Whitehill 1957, pp. 224–226.

- ^ "Ernest J. King Papers 1897–1981, MS 437". Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy. Archived from the original on 10 August 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ a b Buell 1995, pp. 540–541.

- ^ Borneman 2012, p. 491.

- ^ "The Expansion". Lorain City Schools. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "About Our School". Department of Defense Education Activity. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Bill the Goat. "Behind the Scenes: Feeding the Masses at King Hall". U.S. Naval Academy. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Dedication of Buildings". Naval Postgraduate School. 31 May 1956. Archived from the original on 25 July 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Hattendorf 2023, p. xii.

- ^ Payerchin, Richard (30 November 2010). "Adm. Ernest J. King honored locally: Flag flown headed to U.S. Navy training base". Morning Journal. Lisbon, Ohio. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ "The Gallant Hours – Full Cast & Crew". TV Guide. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "MacArthur – Full Cast & Crew". TV Guide. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Deaths – John Dehner". The Washington Post. 10 February 1992. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Midway – Full Cast & Crew". TV Guide. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

References

- Barlow, Jeffrey G. (1998). "Roosevelt and King: The War in the Atlantic and European Theaters". In Marolda, Edward J. (ed.). FDR and the U.S. Navy. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21157-8. OCLC 38764991.

- Blair, Clay Jr. (1975). Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. Philadelphia; New York: J.B. Lippincott and Company. ISBN 0-397-00753-1. OCLC 5070489.

- Borneman, Walter R. (2012). The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy and King – The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-09784-0. OCLC 805654962.

- Buell, Thomas B. (1995). Master of Sea Power: A Biography of Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-092-4. OCLC 5799946.

- Buell, Thomas B. (1998). "Roosevelt and Strategy in the Pacific". In Marolda, Edward J. (ed.). FDR and the U.S. Navy. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21157-8. OCLC 38764991.

- Burtness, Paul S.; Ober, Warren U. (2013). "Research Note: Secretary Forrestal and Admiral King on Admiral Stark: Conflicting Assessments". Australian Journal of Politics and History. 59 (4): 669–676. doi:10.1111/ajph.12038. ISSN 0004-9522.

- Cline, Ray S. (1951). Washington Command Post: The Operations Division (PDF). United States Army in World War II. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, Department of the Army. OCLC 1251644. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- Coles, Michael (January 2001). "Ernest King and the British Pacific Fleet: The Conference at Quebec, 1944 ('Octagon')". The Journal of Military History[. 65 (1): 105–129. doi:10.2307/2677432. ISSN 0899-3718. JSTOR 2677432.

- Davidson, Joel R. (1996). The Unsinkable Fleet: The Politics of U.S. Navy Expansion in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-156-4. OCLC 34472914.

- Gannon, Michael (1991). Operation Drumbeat. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-092088-2. OCLC 24753552.

- Hattendorf, John B. (2023). "Introduction". In Hattendorf, John B. (ed.). HM 30: Reflections on Naval History: Collected Essays. Historical Monographs. Newport, Rhode Island: U.S. Naval War College. pp. xi–xiii. Archived from the original on 10 August 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- Hayes, Grace Person (1982). The History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in World War II: The War against Japan. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-269-9. OCLC 7795125.

- Heinrichs, Walso (1998). "FDR and the Admirals: Strategy and Statecraft". In Marolda, Edward J. (ed.). FDR and the U.S. Navy. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21157-8. OCLC 38764991.

- Hone, Thomas C.; Utz, Curtis A. (2023). History of the Office of the Chief Of Naval Operations 1915–2015. Washington, D.C.: Naval History And Heritage Command, Department of the Navy. ISBN 978-1-943604-02-9. OCLC 1042076000.

- Ismay, Hastings Lionel (1960). The Memoirs of General the Lord Ismay. London: William Heinemann. OCLC 4162506.

- King, Ernest J. (January 1909). "Some Ideas About Organization on Board Ship". United States Naval Institute Proceedings. 35 (1): 1–36. ISSN 0041-798X. Archived from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- King, Ernest J. (7 November 1932). The Influence of National Policy on Strategy (Thesis). Naval War College. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- King, Ernest J.; Whitehill, Walter Muir (1952). Fleet Admiral King: A Naval Record. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-7858-1302-0.}

- Kohnen, David (2018). "Charting a New Course: The Knox-Pye-King Board and Naval Professional Education, 1919–23". Naval War College Review. 71 (3): 121–141. ISSN 0028-1484. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Love, Robert William Jr. (1980). "Ernest Joseph King". In Love, Robert William Jr. (ed.). The Chiefs of Naval Operations. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 137–180. ISBN 0-87021-115-3. OCLC 6142731.

- Miller, Casey L.; Jappert, Carl; Jackson, Matthew (October 2023). "Beating Drumbeat: Lessons Learned in Unified Action from the German U-Boat Offensive Against the United States, January–July 1942" (PDF). Joint Forces Quarterly (111): 131–140. ISSN 1070-0692. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1947). The Battle of the Atlantic, September 1939 – May 1943. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. I. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 21900908.