| External iliac vein | |

|---|---|

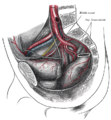

Veins of the abdomen and lower limb - inferior vena cava, common iliac vein, external iliac vein, internal iliac vein, femoral vein and their tributaries. The aorta and its bifurcation (unlabeled) appear in red. | |

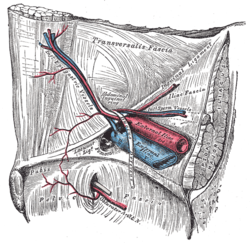

The relations of the femoral and abdominal inguinal rings, seen from within the abdomen. Right side. (External iliac vein is large vein at center.) | |

| Details | |

| Drains from | Lower limbs |

| Source | Femoral veins |

| Drains to | Common iliac vein |

| Artery | External iliac arteries |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vena iliaca externa |

| TA98 | A12.3.10.024 |

| TA2 | 5050 |

| FMA | 18883 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The external iliac veins are large veins that connect the femoral veins to the common iliac veins. Their origin is at the inferior margin of the inguinal ligaments and they terminate when they join the internal iliac veins (to form the common iliac veins).

Both external iliac veins are accompanied along their course by external iliac arteries.

Structure

A continuation of the femoral vein,[1] the external iliac vein starts at the level of the inguinal ligament.[2] It runs beside its corresponding artery and along the brim of the lesser pelvis to unite with the internal iliac vein anterior to the sacroiliac joint where it forms the common iliac vein.[3]

The left external iliac vein remains medial to the artery along its whole path. The right external iliac vein is medial to the artery, but as it ascends, it runs posterior to it.[2]

The external iliac vein is crossed by the ureter and internal iliac artery which both extend towards the middle. In males it is crossed by the vas deferens and in females the round ligament and ovarian vessels cross it. Psoas major lies to its side, except where the artery intervenes.[4]

The external iliac vein may have one valve, but often has no valves.[2]

In addition to pubic veins, the main tributaries of the external iliac veins are the inferior epigastric veins and the deep circumflex iliac vein.[4]

Clinical significance and history

In 1967, Cockett noted anatomical variations which predisposed to compression of the external iliac vein, amongst other veins. Although less common than May-Thurner syndrome, it is being progressively documented due to modern imaging methods. Compression of the left external iliac vein by the right common iliac artery or left hypogastric artery can occur as it crosses over the vein into the pelvis. The right external iliac vein can similarly be compressed. Such compressions may contribute to deep vein thrombosis.[5]

Failure to develop or agenesis of the external iliac vein has been described in association with Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome.[4]

Additional images

-

Diagram showing completion of development of the parietal veins.

-

The arteries of the male pelvis.

-

The veins of the right half of the male pelvis.

-

The spermatic cord in the inguinal canal.

-

External iliac vein. Deep dissection. Serial cross section.

References

- ^ Sinnatamby, Chummy S. (2011). "5". Last's Anatomy: Regional and Applied (12th ed.). Great Britain: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-7020-4839-5. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c Mozes, Geza; Gloviczki, Peter (2014). John J. Bergan & Nisha Bunke-Paquette (ed.). The Vein Book (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-539963-9.

- ^ Netter, Frank H. (2017). James C Reynolds (ed.). The Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations: Digestive System: Part I - The Upper Digestive Tract. Vol. 9 (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-323-38936-5.

- ^ a b c Delancey, John O.L. (2016). "73, True pelvis, pelvic floor and perineum". In Standring, Susan (ed.). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (41st ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1221–1236. ISBN 978-0-7020-6851-5.

- ^ DeRubertis, Brian; Patel, Rhasheet (2017). "35, May-Thurner Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management". In Cassius Iyad Ochoa Chaar (ed.). Current Management of Venous Diseases. Springer International Publishing. pp. 464–465. ISBN 978-3-319-65226-9.

External links

- pelvis at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (pelvicarteries)