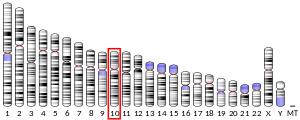

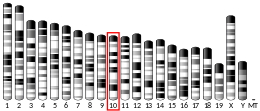

Hexokinase I, also known as hexokinase A and HK1, is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the HK1 gene on chromosome 10. Hexokinases phosphorylate glucose to produce glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), the first step in most glucose metabolism pathways. This gene encodes a ubiquitous form of hexokinase which localizes to the outer membrane of mitochondria. Mutations in this gene have been associated with hemolytic anemia due to hexokinase deficiency. Alternative splicing of this gene results in five transcript variants which encode different isoforms, some of which are tissue-specific. Each isoform has a distinct N-terminus; the remainder of the protein is identical among all the isoforms. A sixth transcript variant has been described, but due to the presence of several stop codons, it is not thought to encode a protein. [provided by RefSeq, Apr 2009][5]

Structure

Hexokinase I is one of four highly homologous hexokinase isoforms in mammalian cells.[6][7]

Gene

The HK1 gene spans approximately 131 kb and consists of 25 exons. Alternative splicing of its 5’ exons produces different transcripts in different cell types: exons 1-5 and exon 8 (exons T1-6) are testis-specific exons; exon 6, located approximately 15 kb downstream of the testis-specific exons, is the erythroid-specific exon (exon R); and exon 7, located approximately 2.85 kb downstream of exon R, is the first 5’ exon for the ubiquitously expressed hexokinase I isoform. Moreover, exon 7 encodes the porin-binding domain (PBD) conserved in mammalian HK1 genes. Meanwhile, the remaining 17 exons are shared among all hexokinase I isoforms.

In addition to exon R, a stretch of the proximal promoter that contains a GATA element, an SP1 site, CCAAT, and an Ets-binding motif is necessary for expression of HK-R in erythroid cells.[6]

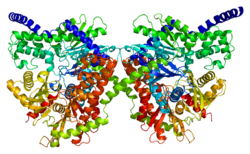

Protein

This gene encodes a 100 kDa homodimer with a regulatory N-terminal domain (1-475), catalytic C-terminal domain (residues 476-917), and an α-helix connecting its two subunits.[6][8][9][10] Both terminal domains are composed of a large subdomain and a small subdomain. The flexible region of the C-terminal large subdomain (residues 766–810) can adopt various positions and is proposed to interact with the base of ATP. Moreover, glucose and G6P bind in close proximity at the N- and C-terminal domains and stabilize a common conformational state of the C-terminal domain.[8][9] According to one model, G6P acts as an allosteric inhibitor which binds the N-terminal domain to stabilize its closed conformation, which then stabilizes a conformation of the C-terminal flexible subdomain that blocks ATP. A second model posits that G6P acts as an active inhibitor that stabilizes the closed conformation and competes with ATP for the C-terminal binding site.[8] Results from several studies suggest that the C-terminal is capable of both catalytic and regulatory action.[11] Meanwhile, the hydrophobic N-terminal lacks enzymatic activity by itself but contains the G6P regulatory site and the PBD, which is responsible for the protein's stability and binding to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM).[6][12][10][13]

Function

As one of two mitochondrial isoforms of hexokinase and a member of the sugar kinase family, hexokinase I catalyzes the rate-limiting and first obligatory step of glucose metabolism, which is the ATP-dependent phosphorylation of glucose to G6P.[8][7][10][14] Physiological levels of G6P can regulate this process by inhibiting hexokinase I as negative feedback, though inorganic phosphate (Pi) can relieve G6P inhibition.[8][12][10] However, unlike HK2 and HK3, hexokinase I itself is not directly regulated by Pi, which better suits its ubiquitous catabolic role.[7] By phosphorylating glucose, hexokinase I effectively prevents glucose from leaving the cell and, thus, commits glucose to energy metabolism.[8][13][12][10] Moreover, its localization and attachment to the OMM promotes the coupling of glycolysis to mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, which greatly enhances ATP production by direct recycling of mitochondrial ATP/ADP to meet the cell's energy demands.[14][10][15] Specifically, OMM-bound hexokinase I binds VDAC1 to trigger opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and release mitochondrial ATP to further fuel the glycolytic process.[10][7]

Another critical function for OMM-bound hexokinase I is cell survival and protection against oxidative damage.[14][7] Activation of Akt kinase is mediated by hexokinase I-VDAC1 coupling as part of the growth factor-mediated phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3)/Akt cell survival intracellular signaling pathway, thus preventing cytochrome c release and subsequent apoptosis.[14][6][10][7] In fact, there is evidence that VDAC binding by the anti-apoptotic hexokinase I and by the pro-apoptotic creatine kinase are mutually exclusive, indicating that the absence of hexokinase I allows creatine kinase to bind and open VDAC.[7] Furthermore, hexokinase I has demonstrated anti-apoptotic activity by antagonizing Bcl-2 proteins located at the OMM, which then inhibits TNF-induced apoptosis.[6][13]

In the prefrontal cortex, hexokinase I putatively forms a protein complex with EAAT2, Na+/K+ ATPase, and aconitase, which functions to remove glutamate from the perisynaptic space and maintain low basal levels in the synaptic cleft.[15]

In particular, hexokinase I is the most ubiquitously expressed isoform out of the four hexokinases, and constitutively expressed in most tissues, though it is majorly found in brain, kidney, and red blood cells (RBCs).[6][8][13][7][15][10][16] Its high abundance in the retina, specifically the photoreceptor inner segment, outer plexiform layer, inner nuclear layer, inner plexiform layer, and ganglion cell layer, attests to its crucial metabolic purpose.[17] It is also expressed in cells derived from hematopoietic stem cells, such as RBCs, leukocytes, and platelets, as well as from erythroid-progenitor cells.[6] Of note, hexokinase I is the sole hexokinase isoform found in the cells and tissues which rely most heavily on glucose metabolism for their function, including brain, erythrocytes, platelets, leukocytes, and fibroblasts.[18] In rats, it is also the predominant hexokinase in fetal tissues, likely due to their constitutive glucose utilization.[12][16]

Clinical significance

Mutations in this gene are associated with type 4H of Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, also known as Russe-type hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSNR).[19] Changes in hexokinase I have also been identified to cause both mild and severe forms of congenital hyperinsulinism.[20][21][22] Due to the crucial role of hexokinase I in glycolysis, hexokinase deficiency has been identified as a cause of erythroenzymopathies associated with hereditary non-spherocytic hemolytic anemia (HNSHA). Likewise, hexokinase I deficiency has resulted in cerebral white matter injury, malformations, and psychomotor retardation, as well as latent diabetes mellitus and panmyelopathy.[6] Meanwhile, hexokinase I is highly expressed in cancers, and its anti-apoptotic effects have been observed in highly glycolytic hepatoma cells.[13][6]

Neurodegenerative disorders

Hexokinase I may be causally linked to mood and psychotic disorders, including unipolar depression (UPD), bipolar disorder (BPD), and schizophrenia via both its roles in energy metabolism and cell survival. For instance, the accumulation of lactate in the brains of BPD and SCHZ patients potentially results from the decoupling of hexokinase I from the OMM, and by extension, glycolysis from mitochondrial oxidative, phosphorylation. In the case of SCHZ, decreasing hexokinase I attachment to the OMM in the parietal cortex resulted in decreased glutamate reuptake capacity and, thus, glutamate spillover from the synapses. The released glutamate activates extrasynaptic glutamate receptors, leading to altered structure and function of glutamate circuits, synaptic plasticity, frontal cortical dysfunction, and ultimately, the cognitive deficits characteristic of SCHZ.[15] Similarly, hexokinase I mitochondrial detachment has been associated with hypothyroidism, which involves abnormal brain development and increased risk for depression, while its attachment leads to neural growth.[14] In Parkinson's disease, hexokinase I detachment from VDAC via Parkin-mediated ubiquitylation and degradation disrupts the MPTP on depolarized mitochondria, consequently blocking mitochondrial localization of Parkin and halting glycolysis.[7] Further research is required to determine the relative hexokinase I detachment needed in various cell types for different psychiatric disorders. This research can also contribute to developing therapies to target causes of the detachment, from gene mutations to interference by factors such as beta-amyloid peptide and insulin.[14]

Retinitis pigmentosa

A heterozygous missense mutation in the HK1 gene (a change at position 847 from glutamate to lysine) has been linked to retinitis pigmentosa.[23][17] Since this substitution mutation is located far from known functional sites and does not impair the enzyme's glycolytic activity, it is likely that the mutation acts through another biological mechanism unique to the retina.[23] Notably, studies in mouse retina reveal interactions between hexokinase I, the mitochondrial metallochaperone Cox11, and the chaperone protein Ranbp2, which serve to maintain normal metabolism and function in the retina. Thus, the mutation may disrupt these interactions and lead to retinal degradation.[17] Alternatively, this mutation may act through the enzyme's anti-apoptotic function, as disrupting the regulation of the hexokinase-mitochondria association by insulin receptors could trigger photoreceptor apoptosis and retinal degeneration.[23][17] In this case, treatments that preserve the hexokinase–mitochondria association may serve as a potential therapeutic approach.[17]

Interactions

Hexokinase I is known to interact with:

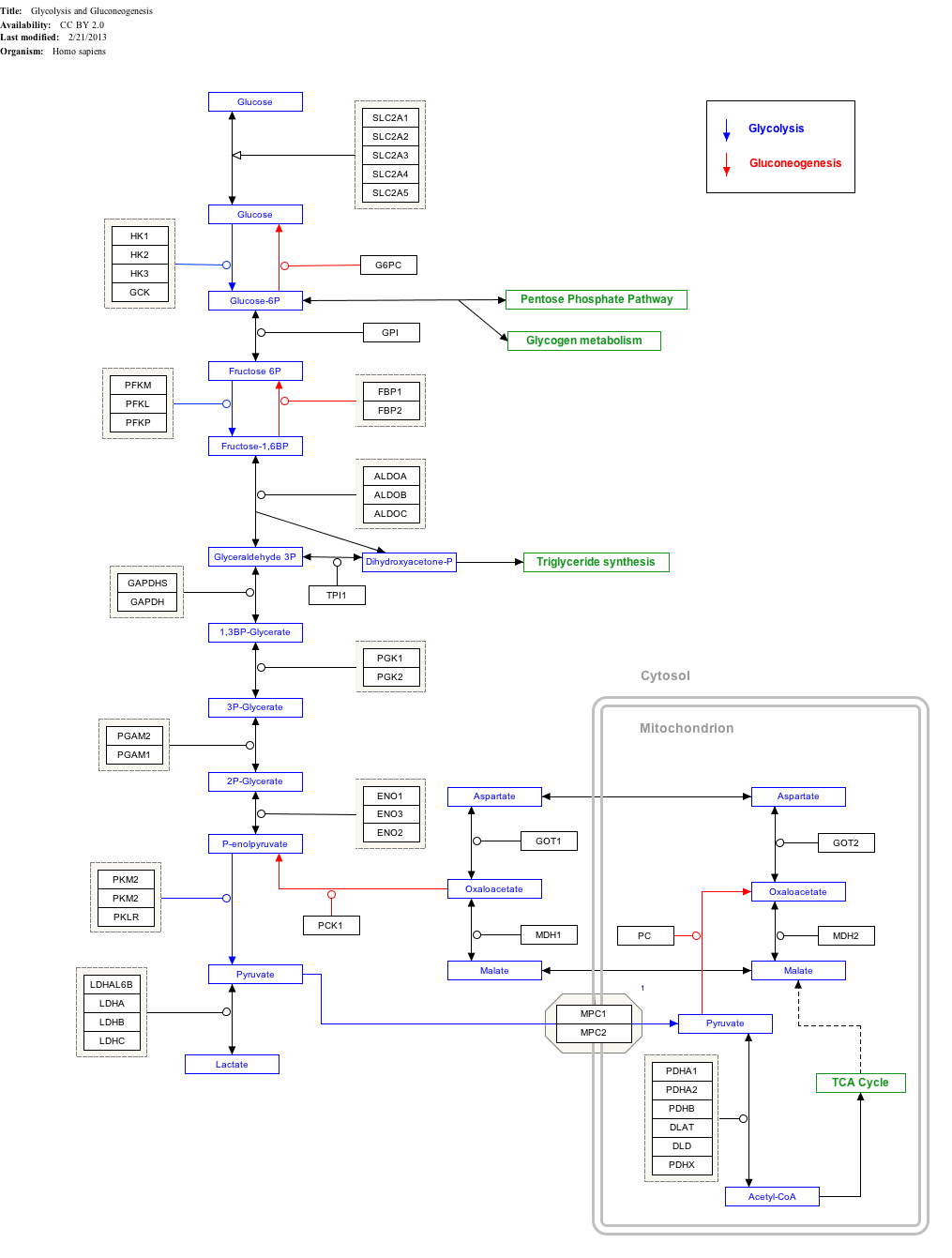

Interactive pathway map

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles.[§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "GlycolysisGluconeogenesis_WP534".

See also

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000156515 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000037012 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: HK1 hexokinase 1".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Murakami K, Kanno H, Tancabelic J, Fujii H (2002). "Gene expression and biological significance of hexokinase in erythroid cells". Acta Haematologica. 108 (4): 204–209. doi:10.1159/000065656. PMID 12432216. S2CID 23521290.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Okatsu K, Iemura S, Koyano F, Go E, Kimura M, Natsume T, et al. (November 2012). "Mitochondrial hexokinase HKI is a novel substrate of the Parkin ubiquitin ligase". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 428 (1): 197–202. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.041. PMID 23068103.

- ^ a b c d e f g Aleshin AE, Zeng C, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Fromm HJ, Honzatko RB (January 1998). "The mechanism of regulation of hexokinase: new insights from the crystal structure of recombinant human brain hexokinase complexed with glucose and glucose-6-phosphate". Structure. 6 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00006-9. PMID 9493266.

- ^ a b Aleshin AE, Kirby C, Liu X, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Fromm HJ, Honzatko RB (March 2000). "Crystal structures of mutant monomeric hexokinase I reveal multiple ADP binding sites and conformational changes relevant to allosteric regulation". Journal of Molecular Biology. 296 (4): 1001–1015. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3494. PMID 10686099.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Robey RB, Hay N (August 2006). "Mitochondrial hexokinases, novel mediators of the antiapoptotic effects of growth factors and Akt". Oncogene. 25 (34): 4683–4696. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209595. PMID 16892082.

- ^ Cárdenas ML, Cornish-Bowden A, Ureta T (March 1998). "Evolution and regulatory role of the hexokinases". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1401 (3): 242–264. doi:10.1016/s0167-4889(97)00150-x. PMID 9540816.

- ^ a b c d Printz RL, Osawa H, Ardehali H, Koch S, Granner DK (February 1997). "Hexokinase II gene: structure, regulation and promoter organization". Biochemical Society Transactions. 25 (1): 107–112. doi:10.1042/bst0250107. PMID 9056853.

- ^ a b c d e Schindler A, Foley E (December 2013). "Hexokinase 1 blocks apoptotic signals at the mitochondria". Cellular Signalling. 25 (12): 2685–2692. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.08.035. PMID 24018046.

- ^ a b c d e f Regenold WT, Pratt M, Nekkalapu S, Shapiro PS, Kristian T, Fiskum G (January 2012). "Mitochondrial detachment of hexokinase 1 in mood and psychotic disorders: implications for brain energy metabolism and neurotrophic signaling". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 46 (1): 95–104. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.018. PMID 22018957.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shan D, Mount D, Moore S, Haroutunian V, Meador-Woodruff JH, McCullumsmith RE (April 2014). "Abnormal partitioning of hexokinase 1 suggests disruption of a glutamate transport protein complex in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research. 154 (1–3): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2014.01.028. PMC 4151500. PMID 24560881.

- ^ a b Reid S, Masters C (1985). "On the developmental properties and tissue interactions of hexokinase". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 31 (2): 197–212. doi:10.1016/s0047-6374(85)80030-0. PMID 4058069. S2CID 40877603.

- ^ a b c d e Wang F, Wang Y, Zhang B, Zhao L, Lyubasyuk V, Wang K, et al. (October 2014). "A missense mutation in HK1 leads to autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 55 (11): 7159–7164. doi:10.1167/iovs.14-15520. PMC 4224578. PMID 25316723.

- ^ Gjesing AP, Nielsen AA, Brandslund I, Christensen C, Sandbæk A, Jørgensen T, et al. (July 2011). "Studies of a genetic variant in HK1 in relation to quantitative metabolic traits and to the prevalence of type 2 diabetes". BMC Medical Genetics. 12: 99. doi:10.1186/1471-2350-12-99. PMC 3161933. PMID 21781351.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 605285

- ^ Hewat TI, Johnson MB, Flanagan SE (7 July 2022). "Congenital Hyperinsulinism: Current Laboratory-Based Approaches to the Genetic Diagnosis of a Heterogeneous Disease". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 13: 873254. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.873254. PMC 9302115. PMID 35872984.

- ^ Rosenfeld E, Ganguly A, De Leon DD (December 2019). "Congenital hyperinsulinism disorders: Genetic and clinical characteristics". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 181 (4): 682–692. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31737. PMC 7229866. PMID 31414570.

- ^ Maiorana A, Lepri FR, Novelli A, Dionisi-Vici C (2022-03-29). "Hypoglycaemia Metabolic Gene Panel Testing". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 13: 826167. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.826167. PMC 9001947. PMID 35422763.

- ^ a b c Sullivan LS, Koboldt DC, Bowne SJ, Lang S, Blanton SH, Cadena E, et al. (September 2014). "A dominant mutation in hexokinase 1 (HK1) causes retinitis pigmentosa". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 55 (11): 7147–7158. doi:10.1167/iovs.14-15419. PMC 4224580. PMID 25190649.

Further reading

- Daniele A, Altruda F, Ferrone M, Silengo L, Romeo G, Archidiacono N, Rocchi M (1992). "Mapping of human hexokinase 1 gene to 10q11----qter". Human Heredity. 42 (2): 107–110. doi:10.1159/000154049. PMID 1572668.

- Magnani M, Bianchi M, Casabianca A, Stocchi V, Daniele A, Altruda F, et al. (July 1992). "A recombinant human 'mini'-hexokinase is catalytically active and regulated by hexose 6-phosphates". The Biochemical Journal. 285 (Pt 1): 193–199. doi:10.1042/bj2850193. PMC 1132765. PMID 1637300.

- Magnani M, Serafini G, Bianchi M, Casabianca A, Stocchi V (January 1991). "Human hexokinase type I microheterogeneity is due to different amino-terminal sequences". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266 (1): 502–505. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)52464-9. PMID 1985912.

- Adams V, Griffin LD, Gelb BD, McCabe ER (June 1991). "Protein kinase activity of rat brain hexokinase". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 177 (3): 1101–1106. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(91)90652-N. PMID 2059200.

- Murakami K, Blei F, Tilton W, Seaman C, Piomelli S (February 1990). "An isozyme of hexokinase specific for the human red blood cell (HKR)". Blood. 75 (3): 770–775. doi:10.1182/blood.V75.3.770.770. PMID 2297576.

- Nishi S, Seino S, Bell GI (December 1988). "Human hexokinase: sequences of amino- and carboxyl-terminal halves are homologous". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 157 (3): 937–943. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(88)80964-1. PMID 3207429.

- Rijksen G, Akkerman JW, van den Wall Bake AW, Hofstede DP, Staal GE (January 1983). "Generalized hexokinase deficiency in the blood cells of a patient with nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia". Blood. 61 (1): 12–18. doi:10.1182/blood.V61.1.12.12. PMID 6848140.

- Bianchi M, Magnani M (1995). "Hexokinase mutations that produce nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia". Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases. 21 (1): 2–8. doi:10.1006/bcmd.1995.0002. PMID 7655856.

- Blachly-Dyson E, Zambronicz EB, Yu WH, Adams V, McCabe ER, Adelman J, et al. (January 1993). "Cloning and functional expression in yeast of two human isoforms of the outer mitochondrial membrane channel, the voltage-dependent anion channel". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (3): 1835–1841. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53930-2. PMID 8420959.

- Aleshin AE, Zeng C, Fromm HJ, Honzatko RB (August 1996). "Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of human brain hexokinase". FEBS Letters. 391 (1–2): 9–10. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00688-6. PMID 8706938. S2CID 44367910.

- Visconti PE, Olds-Clarke P, Moss SB, Kalab P, Travis AJ, de las Heras M, Kopf GS (January 1996). "Properties and localization of a tyrosine phosphorylated form of hexokinase in mouse sperm". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 43 (1): 82–93. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199601)43:1<82::AID-MRD11>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 8720117. S2CID 30206768.

- Mori C, Nakamura N, Welch JE, Shiota K, Eddy EM (May 1996). "Testis-specific expression of mRNAs for a unique human type 1 hexokinase lacking the porin-binding domain". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 44 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199605)44:1<14::AID-MRD2>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 8722688. S2CID 28880251.

- Murakami K, Piomelli S (February 1997). "Identification of the cDNA for human red blood cell-specific hexokinase isozyme". Blood. 89 (3): 762–766. doi:10.1182/blood.V89.3.762. PMID 9028305.

- Ruzzo A, Andreoni F, Magnani M (January 1998). "An erythroid-specific exon is present in the human hexokinase gene". Blood. 91 (1): 363–364. doi:10.1182/blood.V91.1.363. PMID 9414310.

- Travis AJ, Foster JA, Rosenbaum NA, Visconti PE, Gerton GL, Kopf GS, Moss SB (February 1998). "Targeting of a germ cell-specific type 1 hexokinase lacking a porin-binding domain to the mitochondria as well as to the head and fibrous sheath of murine spermatozoa". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 9 (2): 263–276. doi:10.1091/mbc.9.2.263. PMC 25249. PMID 9450953.

- Aleshin AE, Zeng C, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Fromm HJ, Honzatko RB (January 1998). "The mechanism of regulation of hexokinase: new insights from the crystal structure of recombinant human brain hexokinase complexed with glucose and glucose-6-phosphate". Structure. 6 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00006-9. PMID 9493266.

- Ruzzo A, Andreoni F, Magnani M (April 1998). "Structure of the human hexokinase type I gene and nucleotide sequence of the 5' flanking region". The Biochemical Journal. 331 (Pt 2): 607–613. doi:10.1042/bj3310607. PMC 1219395. PMID 9531504.

- Aleshin AE, Zeng C, Bartunik HD, Fromm HJ, Honzatko RB (September 1998). "Regulation of hexokinase I: crystal structure of recombinant human brain hexokinase complexed with glucose and phosphate". Journal of Molecular Biology. 282 (2): 345–357. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1998.2017. PMID 9735292.

- Murakami K, Kanno H, Miwa S, Piomelli S (June 1999). "Human HKR isozyme: organization of the hexokinase I gene, the erythroid-specific promoter, and transcription initiation site". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 67 (2): 118–130. doi:10.1006/mgme.1999.2842. PMID 10356311.