This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

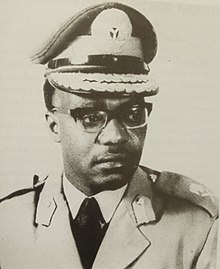

Hassan Katsina | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chief of Army Staff | |

| In office May 1968 – January 1971 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Akahan |

| Succeeded by | David Ejoor |

| Governor of Northern Nigeria | |

| In office 16 January 1966 – 27 May 1967 | |

| Preceded by | Kashim Ibrahim |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished Musa Usman (North-Eastern Nigeria) Usman Faruk (North-Western Nigeria) Audu Bako (Kano) Abba Kyari (North-Centeal Nigeria) David Bamigboye (Kwara) Joseph Gomwalk (Benue-Plateau) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hassan Usman 31 March 1933 Katsina, Northern Region, British Nigeria (now in Katsina State, Nigeria) |

| Died | 24 July 1995 (aged 62) Kaduna, Nigeria |

| Relations |

|

| Parent |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | Military officer |

| Awards | Independence Medal |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1956–1975 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | Congo Crisis Nigerian Civil War |

Hassan Usman Katsina OFR (31 March 1933 – 24 July 1995), titled Chiroman Katsina, was a Nigerian general who was the last Governor of Northern Nigeria. He served as Chief of Army Staff during the Nigerian Civil War and later became the Deputy Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters.

Early life

Hassan Usman was born on 31 March 1933, in Katsina to the Fulani royal family of the Sullubawa clan. His father, Usman Nagogo, was the 48th Emir of Katsina from 1944 to 1981. His grandfather, Muhammadu Dikko, was the 47th Emir of Katsina from 1906 to 1944.

Katsina was educated at the prestigious Barewa College. He then proceeded to the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology in Zaria.[1]

Military career

In 1956, Katsina joined the Nigerian Army.[2] As the military was still under colonial control, he trained at the Mons Officer Cadet School and the prestigious Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst.[3] Following independence, Katsina rose through the ranks of the military. He commandeered troops in Kano and Kaduna, and served as an officer in the intelligence corps in the Congo Crisis, receiving the Congo Medal. He was viewed as a prominent and senior Northern military officer, with close links to the ruling class.

Coups d'état of 1966

On the day of the January 1966 coup d'état, Katsina — a Major serving as the commander of the Kaduna-based 1st Reconnaissance Squadron — received reports of gunfire at the home of Premier of Northern Nigeria Ahmadu Bello. Unaware that Bello had already been killed by Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu's putschist group, Katsina ordered Corporal John Nanzip Shagaya and Sergeant Dantsoho Mohammed on a reconnaissance mission into the city where they found Bello's dead police guard along with the corpses of Brigadier Samuel Ademulegun and his wife.[4] Within a few days, the coup was successfully repressed and General Officer Commanding Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi took power as the first military Head of State.[5] Upon the installation of the military government, Aguiyi-Ironsi appointed Katsina as the Military Governor of Northern Nigeria;[6] in this office, he accepted the surrender of Nzeogwu — who had seized control of Kaduna during the coup — on 17 January.[7] Historian Max Siollun described the appointment as "politically astute" due to Katsina's close ties to the northern political "establishment" that had just lost power after the assassinations of Bello and Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa.[8] Katsina was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel upon the appointment.[9]

As a regional governor, Katsina was an ex officio member of the Supreme Military Council.[10] It was due to this office that Katsina played a role in the Unification Decree to turn Nigeria into a unitary state, later revealing that his public support for the decree was a front and that he knew there would be riots in response to its announcement.[11] Amid rising anti-Igbo sentiment, the ensuing anti-Unification Decree riots would become the first part of massive anti-Igbo pogroms throughout the year.[12] Tensions based on the Unification Decree, grief from the murders of northern leaders in the January failed coup, anti-Igbo conspiracy theories, and other sources rose greatly as misinformation spread across the North rapidly, forcing Katsina to embark on a tour to debunk false rumours that Aguiyi-Ironsi had barred Muslims from making the Hajj.[13]

Although a member of the government, Katsina echoed the growing anger felt by low-level Northern soldiers, using a speech to vow revenge for deaths in the January coup.[14] After months of rising tensions, a mutiny in Abeokuta rapidly led to the July counter-coup that killed Aguiyi-Ironsi and scores of southern soldiers. Katsina — like other senior Northern officers — did not directly take part in the counter-coup but did effectively accept the coup and entered negotiations in Ikeja with the hardline Northern secessionist putschists led by Murtala Mohammed.[15] A group comprising senior civil servants, the British and American ambassadors, and moderate Northern officers along with some surviving Southern colleagues successfully convinced the Murtala faction not to attempt Northern secession and accept Lieutenant Colonel Yakubu Gowon as the Aguiyi-Ironsi's successor as head of state. Following the coup, renewed anti-Igbo pogroms wrecked Northern cities and forced hundreds of thousands of southerners to flee the Northern Region. Katsina became renowned for conciliatory acts like stopping the 1 October mutiny of the 5th battalion in Kano before driving through the city with the Emir personally stopping massacres and looting; additionally, Katsina organized the smuggling of surviving southern officers (including future President Olusegun Obasanjo and his aide-de-camp Lieutenant Chris Ugokwe) to safety.[16] However, while the atrocities were committed by low-level soldiers accompanied by civilians and Katsina actively attempted to stop killings, he also oversaw the conditions that led to the pogroms by giving Northern soldiers broad license to "defend themselves" and authorizing the broadcast of key inflammatory disinformation.[17][18]

Administration

His government chose to carry on with the progress attained by Ahmadu Bello and brought aboard senior civil servants in the region who possessed administrative attributes that could continue with the progress. Key figures in his government included Ibrahim Dasuki; who later became Sultan of Sokoto, Ali Akilu; who later played a prominent role in the creation of states in Nigeria, and Sunday Awoniyi.[19] His administration also saw the rise of the Kaduna Mafia, a new class of young Northern intellectuals, civil servants, and military officers.[20]

During his brief period of leadership, he led the Interim Common Services Agency, an agency which undertook the task of sharing the collective resources of the region in a new decentralized political and economic system of governance.[21] Katsina, also revitalized political linkage with the emirates as a support base for his new administration; and was close to re-introducing the old Native Administrative structures of the colonial system, where emirs played a major role.[22]

Civil War

After surviving both coups and their bloody aftermath, Governor Katsina remained in the Supreme Military Council under Gowon in 1967. As such, he was an Aburi meeting attendee and was involved in the primary discussions with Eastern leader Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu.[23] Katsina reportedly viewed the discussions as a matter of personalities, calling the dispute as one "between one ambitious man and the rest of the country" and deriding Ojukwu as a man who likes "to show how much English he knows." However, as Siollun notes, Ojukwu came to the conference extremely prepared for the crucial constitutional talks and successfully pushed the SMC to make massive concessions. One of those concessions — extreme regional autonomy — was actually supported by Katsina and Western Region Military Governor Robert Adeyinka Adebayo as the initiative would shift power from Gowon to regional governors.[24] However, most agreed concessions at Aburi were not adhered to, leading to the outbreak of the Civil War.

In 1968, General Katsina was appointed Chief of Army Staff after the death of Joseph Akahan. In this position, he led the war effort by doubling the size of troops, blockading of supplies to Biafra, and utilised air support from the United Arab Republic. In 1970, he witnessed the unconditional surrender of Biafra to Nigeria.

Later life and death

Following the 1975 Nigerian coup d'état, General Katsina retired from the military as the most senior experienced military officer at the time. After his retirement, he rejected several government appointments.[25] General Katsina was respected within the military class as he led the promotion of several young officers who later led the military dictatorship in Nigeria.

He was later involved in the formation of political organisations such as the National Party of Nigeria and the Committee of Concerned Citizens.[26] He was also the president of the Nigerian Polo Association, of which his father Emir Usman Nagogo was life president; and pioneer of polo in Nigeria.

General Katsina died on 24 July 1995 in Kaduna.[27]

Military ranks

| Year | Rank |

|---|---|

| 1958 | Second lieutenant |

| 1959 | Lieutenant |

| 1961 | Captain |

| 1963 | Major |

| 1966 | Lieutenant colonel |

| 1968 | Colonel |

| 1969 | Brigadier general |

| 1971 | Major general |

References

- ^ "In memory of late Gen. Hassan Usman Kastina". Daily Trust. 28 July 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ "Nowa Omoigui. January 15, 1966: The role of Major Hassan Usman Katsina". dawodu.com. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ Siollun, Max (2009). Oil, politics and violence: Nigeria's military coup culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-708-3.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ "Nigeria Army Chief Heads A Provisional Government". The New York Times. 17 January 1966. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Stephen Vincent. Should Biafra Survive? Transition No. 32, Aug., 1967, p 54.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. pp. 120–123. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. p. 117. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. p. 121. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Roman Loimeier. Islamic Reform and Political Change in Northern Nigeria, Northwestern University Press, 1997. p 24.ISBN 0810113465

- ^ Blueprint (29 July 2014). "Late General Hassan Katsina: Missing Nigeria leaders' mess". Blueprint Newspapers Limited. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Roman Loimeier. slamic Reform and Political Change in Northern Nigeria, Northwestern University Press, 1997. p 26.ISBN 0810113465

- ^ Emmanuel Ike Udogu. Nigeria In The Twenty-first Century: Strategies for Political Stability and Peaceful Coexistence. p 121-122.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Siollun, Max (3 April 2009). Oil, Politics and Violence : Nigeria's Military Coup Culture (1966-1976). Algora Publishing. pp. 138–144. ISBN 978-0875867083.

- ^ Simone K. Panter-Brick. Soldiers and Oil: The Political Transformation of Nigeria. Routledge, 1978. p 118. ISBN 0-7146-3098-5

- ^ Michael S. Radu, Richard E. Bissell. Africa in the Post-Decolonization Era. Transaction Publishers, 1984. p 43. ISBN 0-87855-496-3

- ^ Burji, B.S.G. (1997). Tributes to man of the people. Burji Publishers. ISBN 978-978-135-052-8. Retrieved 13 April 2015.