This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A set of dice is intransitive (or nontransitive) if it contains dice, with the property that rolls higher than more than half the time, rolls higher than more than half the time, and so on, but does not roll higher than more than half the time. In other words, a set of dice is intransitive if the binary relation – X rolls a higher number than Y more than half the time – on its elements is not transitive. More simply, normally beats , normally beats , but does not normally beat .

It is possible to find sets of dice with the even stronger property that, for each die in the set, there is another die that rolls a higher number than it more than half the time. This is different in that instead of only " does not normally beat " it is now " normally beats ". Using such a set of dice, one can invent games which are biased in ways that people unused to intransitive dice might not expect (see example).[1][2][3][4]

Example

Consider the following set of dice.

- Die A has sides 2, 2, 4, 4, 9, 9.

- Die B has sides 1, 1, 6, 6, 8, 8.

- Die C has sides 3, 3, 5, 5, 7, 7.

The probability that A rolls a higher number than B, the probability that B rolls higher than C, and the probability that C rolls higher than A are all 5/9, so this set of dice is intransitive. In fact, it has the even stronger property that, for each die in the set, there is another die that rolls a higher number than it more than half the time.

Now, consider the following game, which is played with a set of dice.

- The first player chooses a die from the set.

- The second player chooses one die from the remaining dice.

- Both players roll their die; the player who rolls the higher number wins.

If this game is played with a transitive set of dice, it is either fair or biased in favor of the first player, because the first player can always find a die that will not be beaten by any other dice more than half the time. If it is played with the set of dice described above, however, the game is biased in favor of the second player, because the second player can always find a die that will beat the first player's die with probability 5/9. The following tables show all possible outcomes for all three pairs of dice.

| Player 1 chooses die A Player 2 chooses die C |

Player 1 chooses die B Player 2 chooses die A |

Player 1 chooses die C Player 2 chooses die B | |||||||||||

A C |

2 | 4 | 9 | B A |

1 | 6 | 8 | C B |

3 | 5 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | C | A | A | 2 | A | B | B | 1 | C | C | C | ||

| 5 | C | C | A | 4 | A | B | B | 6 | B | B | C | ||

| 7 | C | C | A | 9 | A | A | A | 8 | B | B | B | ||

If one allows weighted dice, i.e., with unequal probability weights for each side, then alternative sets of three dice can achieve even larger probabilities than that each die beats the next one in the cycle. The largest possible probability is one over the golden ratio, .[5]

Variations

Efron's dice

Efron's dice are a set of four intransitive dice invented by Bradley Efron.[4]

The four dice A, B, C, D have the following numbers on their six faces:

- A: 4, 4, 4, 4, 0, 0

- B: 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3

- C: 6, 6, 2, 2, 2, 2

- D: 5, 5, 5, 1, 1, 1

Each die is beaten by the previous die in the list with wraparound, with probability 2/3. C beats A with probability 5/9, and B and D have equal chances of beating the other.[4] If each player has one set of Efron's dice, there is a continuum of optimal strategies for one player, in which they choose their die with the following probabilities, where 0 ≤ x ≤ 3/7:[4]

- P(choose A) = x

- P(choose B) = 1/2 - 5/6x

- P(choose C) = x

- P(choose D) = 1/2 - 7/6x

Miwin's dice

Miwin's dice are a set of nontransitive dice invented in 1975 by the physicist Michael Winkelmann. They consist of three different dice with faces bearing numbers from one to nine; opposite faces sum to nine, ten or eleven. Miwin's dice facilitate generating numbers at random, within a given range, such that each included number is equally-likely to occur. In order to obtain a range that does not begin with 1 or 0, simply add a constant value to bring it into that range (to obtain random numbers between 8 and 16, inclusive, follow the 1 – 9 instructions below, and add seven to the result of each roll).

- 1 – 9: 1 die is rolled (chosen at random): P(1) = P(2) = ... = P(9) = 1/9

- 0 – 80: 2 dice are rolled (chosen at random), always subtract 1: P(0) = P(1) = ... = P(80) = 1/9² = 1/81

The numbers on each die give the sum of 30 and have an arithmetic mean of five. Miwin's dice have six sides, each of which bear a number, depicted in a pattern of dots.

- 1/3 of the die-face values can be divided by three without carry over.

- 1/3 of the die-face values can be divided by three having a carry over of one.

- 1/3 of the die-face values can be divided by three having a carry over of two.

Consider a set of three dice, III, IV and V such that

- die III has sides 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 9

- die IV has sides 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9

- die V has sides 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8

Then:

- the probability that III rolls a higher number than IV is 17/36

- the probability that IV rolls a higher number than V is 17/36

- the probability that V rolls a higher number than III is 17/36

This is because the probability for a given number with all three dice is 11/36, for a given rolled double is 1/36, for any rolled double 1/4. The probability to obtain a rolled double is only 50% compared to normal dice.

-

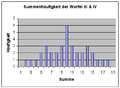

Cumulative frequency type III and IV

-

Cumulative frequency type III and V

-

Cumulative frequency type IV and V

-

Cumulative frequency type III and IV and V = "Miwin-Distribution"

The dice in the first and second Miwin sets have similar attributes: each die bears each of its numbers exactly once, the sum of the numbers is 30, and each number from one to nine is spread twice over the three dice. This attribute characterizes the implementation of intransitive dice, enabling the different game variants. All the games need only three dice, in comparison to other theoretical nontransitive dice, designed in view of mathematics, such as Efron's dice.[6] In the first set, each die is named for the sum of its two lowest numbers. The dots on each die are colored blue, red or black. Each die has the following numbers:

| Die III | with red dots | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 9 | |||

| Die IV | with blue dots | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 9 | |||

| Die V | with black dots | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

Numbers 1 and 9, 2 and 7, and 3 and 8 are on opposite sides on all three dice. Additional numbers are 5 and 6 on die III, 4 and 5 on die IV, and 4 and 6 on die V. The dice are designed in such a way that, for every die, another will usually win against it. The probability that a given die in the sequence (III, IV, V, III) will roll a higher number than the next in the sequence is 17/36; a lower number, 16/36. Thus, die III tends to win against IV, IV against V, and V against III. Such dice are known as nontransitive.

In the second set, each die is named for the sum of its lowest and highest numbers. The dots on each die are colored yellow, white or green. Each die has the following numbers:

| Die IX | with yellow dots | 1 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| Die X | with white dots | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |||

| Die XI | with green dots | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 9 |

The probability that a given die in the sequence (XI, X, IX, XI) will roll a higher number than the next in the sequence is 17/36; a lower number, 16/36. Thus, die XI tends to win against X, X against IX, and IX against XI.

In the third set:

| Die MW 5 | with blue numbers | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 15 | 16 | ||||||||||||

| Die MW 3 | with red numbers | 3 | 4 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||||||||||||

| Die MW 1 | with black numbers | 1 | 2 | 9 | 10 | 17 | 18 |

In the fourth set:

| Die MW 6 | with yellow numbers | 5 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 14 | ||||||||||||

| Die MW 4 | with white numbers | 3 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 17 | 18 | ||||||||||||

| Die MW 2 | with green numbers | 1 | 2 | 11 | 12 | 15 | 16 |

The probability that a given die in the first sequence (5, 3, 1, 5) or the second sequence (6, 4, 2, 6) will roll a higher number than the next in the sequence is 5/9; a lower number, 4/9.

Other distributions

In the 0 – 90 (throw 3 times) distribution, the governing probability is P(0) = P(1) = ... = P(90) = 8/9³ = 8/729. To obtain an equal distribution with numbers from 0 – 90, all three dice are rolled, one at a time, in a random order. The result is calculated based on the following rules:

- 1st throw is 9, 3rd throw is not 9: gives 10 times 2nd throw (possible scores: 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90)

- 1st throw is not 9: gives 10 times 1st throw, plus 2nd throw

- 1st throw is equal to the 3rd throw: gives 2nd throw (possible scores: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

- All dice equal: gives 0

- All dice 9: no score

Sample:

| 1st throw | 2nd throw | 3rd throw | Equation | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 9 | not 9 | 10 times 9 | 90 |

| 9 | 1 | not 9 | 10 times 1 | 10 |

| 8 | 4 | not 8 | (10 times 8) + 4 | 84 |

| 1 | 3 | not 1 | (10 times 1) + 3 | 13 |

| 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 = 7, gives 8 | 8 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | all equal | 0 |

| 9 | 9 | 9 | all 9 | - |

This gives 91 numbers, from 0 – 90 with the probability of 8 / 9³, 8 × 91 = 728 = 9³ − 1. In the 0 – 103 (throw 3 times) distribution, the governing probability is P(0) = P(1) = ... = P(103) = 7/9³ = 7/729. This gives 104 numbers from 0 – 103 with the probability of 7 / 9³, 7 × 104 = 728 = 9³ − 1

In the 0 – 728 (throw 3 times) distribution, the governing probability is P(0) = P(1) = ... = P(728) = 1 / 9³ = 1 / 729. This gives 729 numbers, from 0 – 728, with the probability of 1 / 9³. This system yields this maximum: 8 × 9² + 8 × 9 + 8 × 9° = 648 + 72 + 8 = 728 = 9³ − 1. One die is rolled at a time, taken at random. Create a number system of base 9:

- 1 must be subtracted from the face value of every roll because there are only 9 digits in this number system ( 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 )

- (1st throw) × 81 + (2nd throw) × 9 + (3rd throw) × 1

Examples:

| 1st throw | 2nd throw | 3rd throw | Equation | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 × 9² + 8 × 9 + 8 | 728 |

| 4 | 7 | 2 | 3 × 9² + 6 × 9 + 1 | 298 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 × 9² + 4 × 9 + 0 | 117 |

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 × 9² + 3 × 9 + 3 | 30 |

| 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 × 9² + 6 × 9 + 6 | 546 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 × 9² + 0 × 9 + 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 2 | 6 | 3 × 9² + 1 × 9 + 5 | 257 |

Games

Since the middle of the 1980s, the press wrote about the games.[7] Winkelmann presented games himself, for example, in 1987 in Vienna, at the "Österrechischen Spielefest, Stiftung Spielen in Österreich", Leopoldsdorf, where "Miwin's dice" won the prize "Novel Independent Dice Game of the Year".

In 1989, the games were reviewed by the periodical "Die Spielwiese".[8] At that time, 14 alternatives of gambling and strategic games existed for Miwin's dice. The periodical "Spielbox" had two variants of games for Miwin's dice in the category "Unser Spiel im Heft" (now known as "Edition Spielbox"): the solitaire game 5 to 4, and the two-player strategic game Bitis.

In 1994, Vienna's Arquus publishing house published Winkelmann's book Göttliche Spiele,[9] which contained 92 games, a master copy for four game boards, documentation about the mathematical attributes of the dice and a set of Miwin's dice. There are even more game variants listed on Winkelmann's website.[10]

Solitaire games and games for up to nine players have been developed. Games are appropriate for players over six years of age. Some games require a game board; playing time varies from 5 to 60 minutes.

In the 1st variant, two dice are rolled, chosen at random, one at a time. Each pair is scored by multiplying the first by nine and subtracting the second from the result: 1st throw × 9 − 2nd throw. This variant provides numbers from 0 – 80 with a probability of 1 / 9² = 1 / 81.

Examples:

| 1st throw | 2nd throw | Equation | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 9 | 9 × 9 − 9 | 72 |

| 9 | 1 | 9 × 9 − 1 | 80 |

| 1 | 9 | 9 × 1 − 9 | 0 |

| 2 | 9 | 9 × 2 − 9 | 9 |

| 2 | 8 | 9 × 2 − 8 | 10 |

| 8 | 4 | 9 × 8 − 4 | 68 |

| 1 | 3 | 9 × 1 − 3 | 6 |

In the 2nd variant, two dice are rolled, chosen at random, one at a time. This variant provides numbers from 0 – 80 with a probability of 1 / 9² = 1 / 81. The pair is scored according to the following rules:

- 1st throw is 9: gives 10 × 2nd throw − 10

- 1st throw is not 9: gives 10 × 1st throw + 2nd throw − 10

Examples:

| 1st throw | 2nd throw | Equation | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 9 | 10 × 9 − 10 | 80 |

| 9 | 1 | 10 × 1 − 10 | 0 |

| 8 | 4 | 10 × 8 + 4 − 10 | 74 |

| 1 | 3 | 10 × 1 + 3 − 10 | 3 |

In the 3rd variant, two dice are rolled, chosen at random, one at a time. The score is obtained according to the following rules:

- Both throws are 9: gives 0

- 1st throw is 9 and 2nd throw is not 9: gives 10 × 2nd throw

- 1st throw is 8: gives 2nd throw

- All others: gives 10 × 1st throw − 2nd throw

Examples:

| 1st throw | 2nd throw | Equation | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 9 | - | 0 |

| 9 | 3 | 10 × 3 | 30 |

| 8 | 4 | 1 × 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 9 | 5 × 10 + 9 | 59 |

Intransitive dice set for more than two players

A number of people have introduced variations of intransitive dice where one can compete against more than one opponent.

Three players

Oskar dice

Oskar van Deventer introduced a set of seven dice (all faces with probability 1/6) as follows:[11]

- A: 2, 2, 14, 14, 17, 17

- B: 7, 7, 10, 10, 16, 16

- C: 5, 5, 13, 13, 15, 15

- D: 3, 3, 9, 9, 21, 21

- E: 1, 1, 12, 12, 20, 20

- F: 6, 6, 8, 8, 19, 19

- G: 4, 4, 11, 11, 18, 18

One can verify that A beats {B,C,E}; B beats {C,D,F}; C beats {D,E,G}; D beats {A,E,F}; E beats {B,F,G}; F beats {A,C,G}; G beats {A,B,D}. Consequently, for arbitrarily chosen two dice there is a third one that beats both of them. Namely,

- G beats {A,B}; F beats {A,C}; G beats {A,D}; D beats {A,E}; D beats {A,F}; F beats {A,G};

- A beats {B,C}; G beats {B,D}; A beats {B,E}; E beats {B,F}; E beats {B,G};

- B beats {C,D}; A beats {C,E}; B beats {C,F}; F beats {C,G};

- C beats {D,E}; B beats {D,F}; C beats {D,G};

- D beats {E,F}; C beats {E,G};

- E beats {F,G}.

Whatever the two opponents choose, the third player will find one of the remaining dice that beats both opponents' dice.

Grime dice

Dr. James Grime discovered a set of five dice as follows:[12][13]

- A: 2, 2, 2, 7, 7, 7

- B: 1, 1, 6, 6, 6, 6

- C: 0, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5

- D: 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 9

- E: 3, 3, 3, 3, 8, 8

The colours are often as shown below

- A: Red

- B: Blue

- C: Green

- D: Yellow

- E: Magenta

One can verify that, when the game is played with one set of Grime dice:

- A beats B beats C beats D beats E beats A (first chain);

- A beats C beats E beats B beats D beats A (second chain).

However, when the game is played with two such sets, then the first chain remains the same, except that D beats C, but the second chain is reversed (i.e. A beats D beats B beats E beats C beats A). Consequently, whatever dice the two opponents choose, the third player can always find one of the remaining dice that beats them both (as long as the player is then allowed to choose between the one-die option and the two-die option):

Sets chosen

by opponentsWinning set of dice Type Number A B E 1 A C E 2 A D C 2 A E D 1 B C A 1 B D A 2 B E D 2 C D B 1 C E B 2 D E C 1

Four players

It has been proved that a four player set would require at least 19 dice.[12][14] In July 2024 GitHub user NGeorgescu published a set of 23 eleven sided dice which satisfy the constraints of the four player intransitive dice problem.[15] The set has not been published in an academic journal or been peer-reviewed.

Georgescu dice

In 2024, American scientist Nicholas S. Georgescu discovered a set of 23 dice which solve the four-player intransitive dice problem.[16]

| 0 | 40 | 61 | 83 | 105 | 116 | 158 | 173 | 203 | 213 | 234 |

| 1 | 29 | 46 | 89 | 109 | 119 | 153 | 175 | 196 | 226 | 243 |

| 2 | 41 | 54 | 72 | 113 | 122 | 148 | 177 | 189 | 216 | 252 |

| 3 | 30 | 62 | 78 | 94 | 125 | 143 | 179 | 205 | 229 | 238 |

| 4 | 42 | 47 | 84 | 98 | 128 | 138 | 181 | 198 | 219 | 247 |

| 5 | 31 | 55 | 90 | 102 | 131 | 156 | 183 | 191 | 209 | 233 |

| 6 | 43 | 63 | 73 | 106 | 134 | 151 | 162 | 184 | 222 | 242 |

| 7 | 32 | 48 | 79 | 110 | 137 | 146 | 164 | 200 | 212 | 251 |

| 8 | 44 | 56 | 85 | 114 | 117 | 141 | 166 | 193 | 225 | 237 |

| 9 | 33 | 64 | 91 | 95 | 120 | 159 | 168 | 186 | 215 | 246 |

| 10 | 45 | 49 | 74 | 99 | 123 | 154 | 170 | 202 | 228 | 232 |

| 11 | 34 | 57 | 80 | 103 | 126 | 149 | 172 | 195 | 218 | 241 |

| 12 | 23 | 65 | 86 | 107 | 129 | 144 | 174 | 188 | 208 | 250 |

| 13 | 35 | 50 | 69 | 111 | 132 | 139 | 176 | 204 | 221 | 236 |

| 14 | 24 | 58 | 75 | 92 | 135 | 157 | 178 | 197 | 211 | 245 |

| 15 | 36 | 66 | 81 | 96 | 115 | 152 | 180 | 190 | 224 | 231 |

| 16 | 25 | 51 | 87 | 100 | 118 | 147 | 182 | 206 | 214 | 240 |

| 17 | 37 | 59 | 70 | 104 | 121 | 142 | 161 | 199 | 227 | 249 |

| 18 | 26 | 67 | 76 | 108 | 124 | 160 | 163 | 192 | 217 | 235 |

| 19 | 38 | 52 | 82 | 112 | 127 | 155 | 165 | 185 | 207 | 244 |

| 20 | 27 | 60 | 88 | 93 | 130 | 150 | 167 | 201 | 220 | 230 |

| 21 | 39 | 68 | 71 | 97 | 133 | 145 | 169 | 194 | 210 | 239 |

| 22 | 28 | 53 | 77 | 101 | 136 | 140 | 171 | 187 | 223 | 248 |

Li dice

Youhua Li subsequently developed a set of 19 dice with 171 faces each that solves the four-player problem. This has been shown to be extensible for any number of dice given a domination graph with n nodes, producing dice with n(n−1)/2 faces.[17]

Intransitive 12-sided dice

In analogy to the intransitive six-sided dice, there are also dodecahedra which serve as intransitive twelve-sided dice. The points on each of the dice result in the sum of 114. There are no repetitive numbers on each of the dodecahedra.

Miwin's dodecahedra (set 1) win cyclically against each other in a ratio of 35:34.

The miwin's dodecahedra (set 2) win cyclically against each other in a ratio of 71:67.

Set 1:

| D III | purple | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 18 | ||||||

| D IV | red | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 17 | 18 | ||||||

| D V | dark grey | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

-

D III

-

D IV

-

D V

Set 2:

| D VI | cyan | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 17 | 18 | ||||||

| D VII | pear green | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||||||

| D VIII | light grey | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

-

D VI

-

D VII

-

D VIII

Intransitive prime-numbered 12-sided dice

It is also possible to construct sets of intransitive dodecahedra such that there are no repeated numbers and all numbers are primes. Miwin's intransitive prime-numbered dodecahedra win cyclically against each other in a ratio of 35:34.

Set 1: The numbers add up to 564.

| PD 11 | grey to blue | 13 | 17 | 29 | 31 | 37 | 43 | 47 | 53 | 67 | 71 | 73 | 83 |

| PD 12 | grey to red | 13 | 19 | 23 | 29 | 41 | 43 | 47 | 59 | 61 | 67 | 79 | 83 |

| PD 13 | grey to green | 17 | 19 | 23 | 31 | 37 | 41 | 53 | 59 | 61 | 71 | 73 | 79 |

-

PD 11

-

PD 12

-

PD 13

Set 2: The numbers add up to 468.

| PD 1 | olive to blue | 7 | 11 | 19 | 23 | 29 | 37 | 43 | 47 | 53 | 61 | 67 | 71 |

| PD 2 | teal to red | 7 | 13 | 17 | 19 | 31 | 37 | 41 | 43 | 59 | 61 | 67 | 73 |

| PD 3 | purple to green | 11 | 13 | 17 | 23 | 29 | 31 | 41 | 47 | 53 | 59 | 71 | 73 |

-

PD 1

-

PD 2

-

PD 3

Generalized Muñoz-Perera's intransitive dice

A generalization of sets of intransitive dice with faces is possible.[18] Given , we define the set of dice as the random variables taking values each in the set with

,

so we have fair dice of faces.

To obtain a set of intransitive dice is enough to set the values for with the expression

,

obtaining a set of fair dice of faces

Using this expression, it can be verified that

,

So each die beats dice in the set.

Examples

3 faces

| 1 | 6 | 8 | |

| 2 | 4 | 9 | |

| 3 | 5 | 7 |

The set of dice obtained in this case is equivalent to the first example on this page, but removing repeated faces. It can be verified that .

4 faces

| 1 | 8 | 11 | 14 | |

| 2 | 5 | 12 | 15 | |

| 3 | 6 | 9 | 16 | |

| 4 | 7 | 10 | 13 |

Again it can be verified that .

6 faces

| 1 | 12 | 17 | 22 | 27 | 32 | |

| 2 | 7 | 18 | 23 | 28 | 33 | |

| 3 | 8 | 13 | 24 | 29 | 34 | |

| 4 | 9 | 14 | 19 | 30 | 35 | |

| 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 36 | |

| 6 | 11 | 16 | 21 | 26 | 31 |

Again . Moreover .

See also

- Blotto games

- Freivalds' algorithm

- Go First Dice

- Nontransitive game

- Rock paper scissors

- Condorcet's voting paradox

References

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Efron's Dice". Wolfram MathWorld. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Bogomolny, Alexander. "Non-transitive Dice". Cut the Knot. Archived from the original on 2016-01-12.

- ^ Savage, Richard P. (May 1994). "The Paradox of Nontransitive Dice". The American Mathematical Monthly. 101 (5): 429–436. doi:10.2307/2974903. JSTOR 2974903.

- ^ a b c d Rump, Christopher M. (June 2001). "Strategies for Rolling the Efron Dice". Mathematics Magazine. 74 (3): 212–216. doi:10.2307/2690722. JSTOR 2690722. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Trybuła, Stanisław (1961). "On the paradox of three random variables". Applicationes Mathematicae. 4 (5): 321–332. doi:10.4064/am-5-4-321-332.

- ^ http://www.miwin.com/ click "Miwin'sche Würfel 2", then check attributes

- ^ Austrian paper "Das Weihnachtsorakel, Spieltip "Ein Buch mit zwei Seiten", the Standard 18.Dez..1994, page 6, Pöppel-Revue 1/1990 page 6 and Spielwiese 11/1990 page 13, 29/1994 page 7

- ^ 29/1989 page 6

- ^ The book on the German version of Amazon

- ^ Winkelmann's homepage

- ^ Pegg, Ed Jr. (2005-07-11). "Tournament Dice". Math Games. Mathematical Association of America. Archived from the original on 2005-08-04. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ a b Grime, James. "Non-transitive Dice". Archived from the original on 2016-05-14.

- ^ Pasciuto, Nicholas (2016). "The Mystery of the Non-Transitive Grime Dice". Undergraduate Review. 12 (1): 107–115 – via Bridgewater State University.

- ^ Reid, Kenneth; McRae, A.A.; Hedetniemi, S.M.; Hedetniemi, Stephen (2004-01-01). "Domination and irredundance in tournaments". The Australasian Journal of Combinatorics [electronic only]. 29.

- ^ Georgescu, Nicholas. "math_problems/intransitive.ipynb at main · NGeorgescu/math_problems". GitHub. Archived from the original on 27 March 2025. Retrieved 2025-03-27.

- ^ Georgescu, Nicholas S. (2024). "Georgescu Dice - Four-Player Intransitive Solution". GitHub.

- ^ Youhua Li (2024). "Li Dice - General n-player Extension". GitHub.

- ^ Muñoz Perera, Adrián. "A generalization of intransitive dice" (PDF). Retrieved 15 December 2024.

Sources

- Gardner, Martin (2001). The Colossal Book of Mathematics: Classic Puzzles, Paradoxes, and Problems: Number Theory, Algebra, Geometry, Probability, Topology, Game Theory, Infinity, and Other Topics of Recreational Mathematics (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 286–311.[ISBN missing]

- Spielerische Mathematik mit Miwin'schen Würfeln (in German). Bildungsverlag Lemberger. ISBN 978-3-85221-531-0.

External links

- MathWorld page

- Ivars Peterson's MathTrek - Tricky Dice Revisited (April 15, 2002)

- Jim Loy's Puzzle Page

- Miwin official site (in German)

- Open Source nontransitive dice finder

- Non-transitive Dice by James Grime

- Maths Gear

- Conrey, B., Gabbard, J., Grant, K., Liu, A., & Morrison, K. (2016). Intransitive dice. Mathematics Magazine, 89(2), 133-143. Awarded by Mathematical Association of America[permanent dead link]

- Timothy Gowers' project on intransitive dice

- Klarreich, Erica (2023-01-19). "Mathematicians Roll Dice and Get Rock-Paper-Scissors". Quanta Magazine.

- Adrián Muñoz Perera's site'

- Introduction to Non-Transitive Gambling Bets for Magicians by Bruce Carlley. This is the ONLY book on this topic.

![{\displaystyle \mathbb {P} \left[D_{n}=v_{n,j}\right]={\frac {1}{J}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b72b67b58d2728bdac675623b05cb59af1611919)

![{\displaystyle \mathbb {P} \left[D_{m}<D_{n}\right]={\frac {1}{2}}+{\frac {1}{2N}}-{\frac {(n-m){\text{mod}}(N)}{N^{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/991a6472c768dfc502963f542003b0dc0b696bc3)